John Coltrane revolutionized American music.Bill Cole is revolutionizing his listeners.

THE John Coltrane Memorial World Music and Lecture Demonstration Series, a program as far reaching as its title is long, came to Dartmouth with Bill Cole when he signed on as an assistant professor of music this year. With seven major concerts, two poetry and sculpture sessions, three lectures and several other related events in the Hopkins Center, the Coltrane series is an ambitious year-long excursion that starts with the AfricanAmerican creative tradition and spreads widely into other non-Western cultures.

As the concerts, lectures and other events have unfolded this fall, the audience reaction has ranged from delighted discovery to satisfied expectation to smiling bewilderment to occasional exasperation, the same kind of mixed reaction that Coltrane experienced in his lifetime. Attendance of the series has been solid not always standing room only, but at least two of the major concerts have filled all but the rear corners of the 950-seat Spaulding Auditorium.

Ironically, while the series is built around Coltrane, it contains none of the late saxophonist's music. Instead, the binding force is the Coltrane spirit the intensity, generosity, universality and freedom that he and his music represent. "John Coltrane was a giant, perhaps the foremost musician this country has ever produced," Cole says. "He had a tremendous dedication to music. He was constantly growing, revolutionizing the saxophone and revolutionizing music. He led many younger musicians. And most important, he looked outside the western European tradition, into African, Indian and other cultures around the world.

THERE is a further aspect to Coltrane, a tragic quality to his life, that has made him a cult hero among those who have seriously studied him. For most of his early years, Coltrane had a severe drug and alcohol problem that he finally oyer' came with great spiritual effort in 1957, only to die ten years later, not yet 41, from the effects of that early abuse. Black poet Jayne Cortez, reading her work with a voice like a jazz instrument, perhaps like the surging saxophone that Coltrane played, was the featured performer in one of the typically untypical Coltrane series events. Her poetry was accompanied by Cole, blowing wailing tones through a tassled Chinese muzette, and by percussionist Warren Smith, rapping dark rhythms from drums, cymbals and a halfdozen exotic African instruments. For the first few minutes, some members of the audience had to resist looking at one another. But when it was over, there was a unanimous thunder of applause that tried, unsuccessfully, to get Miss Cortez to read more.

Two other performers in the series have been men who played with Coltrane: fellow saxophonist Archie Shepp, known in his own right as an innovator in improvisational music, and pianist McCoy Tyner, who played in the Coltrane band in the early 1960s during some-revolutionary work on the new modal system of jazz.

Other guests in the first part of the series have been either Africans or African-Americans (a term Cole prefers to the less balanced "Afro-American"). Abraham Adzenyah is a master drummer from Ghana. Fela Sowande is a noted musical scholar and philosopher from Nigeria, a man whose writings and thought have had a strong influence on Cole. Mel Edwards is a sculptor from Los Angeles who has done some forceful work with steel chain and barbed wire. Sam Rivers is a New York composer and saxophonist who once played with Miles Davis.

The Rivers concert opened the Coltrane series in late September. Joining Warren Smith and bassist Vishnu Wood as sidemen to Rivers, Cole made his Dartmouth debut on the muzette and two other non-European reeded instruments he specializes in, the Indian shenai and the Korean sona. "It was a brilliant concert 'hat showed a high degree of musicianship, especially in Bill's case," says Associate Professor Jon H. Appleton, acting chairman of the Music Department. "I'd say it Was a spectacular debut for a new member of the Dartmouth faculty."

In January, the Coltrane series makes an eastward shift by bringing in the wesleyan University Gamelan Ensemble, some of the foremost student practitioners of native Indonesian orchestral music. In February comes Gen'ichi Tsuage, curator of musical instruments at Wesleyan and an expert in Japanese and Southeast Asian music, followed by the Japanese Music Ensemble featuring traditional works on the koto and shakuhachi. In late March and early April, David Baker, a musician and member of the Indiana University faculty, makes a brief residency to give lectures on orchestration and to join Cole in two recitals.

IT is in this turn from Africa to the Orient that Cole begins to shine. His predecessors at Dartmouth concentrated on African-American music, in most cases their own. Starting in 1969, the lineup has included trumpeter Don Cherry, bassist Willie Ruff, pianist Dwike Mitchell, and saxophonists Robert Northern and Lucky Thompson - all fairly well-known musicians who were a draw by themselves and who had strings to even bigger names. Ruff and Mitchell brought Dizzy Gillespie to Dartmouth and made a recording with him here.

Cole swings his heaviest weight in academia. With bachelor's and master's degrees from the University of Pittsburgh and a Ph.D. from Wesleyan, he had five years of teaching experience, including two years as an assistant professor at Amherst, before coming to Dartmouth in July. He is a contributor to Downbeat and Coda magazines and is author of Miles Davis: AMusical Biography, published this year by William Morrow & Co. A second book examining the style of Coltrane is in progress.

"Bill Cole represents a departure from past procedures," Appleton says. "While the previous men were good performers and gave us spectacular concerts, Bill is trained as an ethnomusicologist and can offer substantive courses in AfricanAmerican and other non-Western traditions. We've been looking for a person like Bill Cole for a long time."

Cole, like Coltrane, can bridge the long gap between Africa and the Orient. Coltrane did it on the strength of his musical genius. Cole's bridge is built on a substantial academic foundation. Which is probably why Cole, unlike the five men who preceded him in five previous years, has a three-year contract with Dartmouth.

For Bill Cole, John Coltrane was an early introduction to the intensity of African-American feeling. The son of a Pittsburgh dentist, Cole grew up in a relatively comfortable and subdued household. He went to a grade school where black children made up only three per cent of the student body. His early musical training was on the piano, then the cello. His older brother showed obvious talent as a painter, and Bill had to be a tolerant younger brother. "I grew up mediating disputes, watching out not to bother my older brother, being a good kid."

As a trustworthy child, Cole was allowed plenty of freedom, and as an early teenager he spent long hours with his friends, listening to the sophisticated jazz that blossomed in the 19505. Through bassist Paul Chambers, a local Pittsburgh hero, Cole's attention was drawn to Miles Davis, then on to John Coltrane.

COLTRANE joined the Miles Davis group in 1955 after an earlier apprenticeship with such musicians as Dizzy Gillespie, Earl Bostic, and Sonny Rollins. Except for a brief interruption in 1957, Coltrane stayed with Davis for nearly five years, developing the driving new style that would give birth to so much innovation in the next decade.

He brought new scale combinations, rhythms, textures and tones to the tenor saxophone and later to the soprano saxophone. While Davis and his mentor, Charlie Parker, played music that progressed mostly by chords, Coltrane drew away from these progressions and strung the chords into lines of notes that could be repeated in varied combinations, in "sheets of sound" with different rhythms and flavors.

The innovations were demanding. In order to fit in more combinations, permutations, textures and resyncopations of these modes, Coltrane had to play with increasing intensity without compromising technical quality. Although his innovations were drawn from and shared with other musicians, Coltrane is recognized for the unmatched genius with which he performed the new music on the saxophone. Through his ability, he created effects that still defy standard musical notation.

Like many others, Cole merges a mystical streak into his more traditional technical analysis of Coltrane's work. He sees shadows of other worlds in the three - layered tones, pentatonic scales, and the groaning, whooping, screaming sounds that came out of Coltrane's music. "He was African-American, a musician, and, like most hyphenated Americans, the source of his music was in another part of the world, in a land which he was unable to visit during his own lifetime but whose life forces transcended bodies of water and land, compelling him to respond to the patterns of traditional African societies," Cole says in his dissertation on Coltrane's style.

Although he never did travel to Africa, Coltrane in his later years actively studied the musical traditions of that continent, as well as the work of a number of Indian musicians, notably Ravi Shankar. Toward the end of his life Coltrane did go to Japan, a trip that also was a source of inspiration in his work.

COLE'S interest in these other worlds first blossomed at Wesleyan: "It was a very expansive experience for me. Wesleyan has a fine program of AfricanAmerican and other non-Western music, and it really broadened my horizons. Even though I had listened to Coltrane, say, several hundred times and had heard mam other musicians, I think I still had a rather conservative view of music. In fact, I had still led a pretty sheltered life ... I never had a black instructor until my second year of graduate school."

At Wesleyan Cole met Adzenyah, Tsuage, the Indonesian musicians, and some of the other artists and scholars that have helped him in his Coltrane series. It also was at Wesleyan that Cole encountered Clifford Brown, who as his faculty adviser introduced him to the Chinese muzette. Although he had spent years at the piano and cello, Cole says he had an immediate feeling the muzette was the instrument that had been waiting for him all that time.

Cole organized and directed his first Coltrane series at Amherst in 1972, aided by a grant from the National Endowment for the Arts. With similar grants, the series continued at Amherst a year later and is now running a third time at Dartmouth.

The Coltrane series runs in a sequence that fits the pattern of courses Cole is teaching in the Music Department. This fall and winter he is teaching World Music I, a survey of African and AfricanAmerican music, and World Music 11, covering Indonesian, Japanese, Chinese, and Southeast Asian music. Next year his courses will cover Western Asian and European folk music, then American Indian, Polynesian, Micronesian and Melanesian music. Cole also has an African-American music theory course going this fall, a John Coltrane seminar in the winter, and a course on improvisational techniques in the spring.

STANDING in the classroom, wearing a yellow striped jersey under a sleeveless purple T-shirt, his head crowned with a round natural hairdo, Cole appears disarmingly casual beside the solemn Steinway piano. He talks animatedly to his students, walking back and forth with springy steps, rolling his hands and bending his body in an almost oriental manner. Both in and out of the classroom, he gives individual attention on large and small matters. One student gets piano lessons again after having given them up in high school. Another student gets Coles interested reaction to the stamps on a postcard that has come from China. Another student is conducted to a listening room with a recording of Coltrane music that won't be heard in the concert series.

Before he signed the contract to come to Dartmouth, Cole probably had to do some bargaining to make sure the Coltrane series would come along with him. So fertile bargain has etched extra fatigue lines in his face, some of them probably drawn in the weeks of organizing, directing and rehearsing for an ambitious series which, in relation to its scope, is being done on a shoestring. Some of the new creases can probably be attributed to watching the verdict slowly come in from many different sources and trying to decide which opinion is representative.

The most unusual review of a Coltrane series event so far was an imitative (and, if the old saw holds, a sincerely flattering) tone poem written after the Rivers concert by Mike Mosher of The Dartmouth. Two paragraphs describing the postintermission program are typical of the review:

Vishnu Wood opened with bass harmonics, then a knobby riff occasionally surging with beating wings and chunky chords. Sam Rivers stepped out to add flute: a nice pair like an old lion and a peacock, equally deep and airy. Smith and Cole returned to a nice slow repetitive tune, musical flame licking out Of the foursome. Good to lean back here, enjoy the pop melodic bits of sparkling flute, horn ribbons, bass and drums, a bit more conventional only a few years ahead of its time.

Cole played on, Smith varied the sound of his drums with a moist finger to the head, Rivers plummeted in with soprano sax to ugly moments of pure horn terror angrily snaking out of the dense underbrush of bass and drums. Horns played tag under the bigtop of drum rolls and bass patter, then like an atonal circus parade of the deformed. All raced to rich patterns, stomach-tightening thunderstorms....

On the other hand, the Archie Shepp concert struck some foul notes in the opinion of The Dartmouth's Larry Habegger, who found the performance "arrogant" and "exasperating," and said he felt he had been "ripped off." A more moderate view came from Gregory Payne, a junior who has been playing the saxophone and listening to Coltrane since his early teens: "There were some parts of the concert I wasn't too impressed with, but there were times that Shepp made those hard driving runs like Coltrane would have played, and that made it all worthwhile."

Coltrane, of course, got his share of criticism from contemporaries who accused him of groping incoherently and Playing meaningless strings of notes. Less than a week before he died, Coltrane was asked for some sleeve notes for a new album. He replied: "By this point I don't know what else can be said in words about what I'm doing. Let the music speak for itself."

With the Coltrane series, Cole has learned that in opening doors to sometimes Grange new worlds, he hasn't been able to Please everyone. But even for those who haven't understood or have expected something else, the Coltrane series has fought a general respect for its goals, and as nudged a curiosity to know what else lies beneath the cultural iceberg that Bill Cole is pulling to shore.

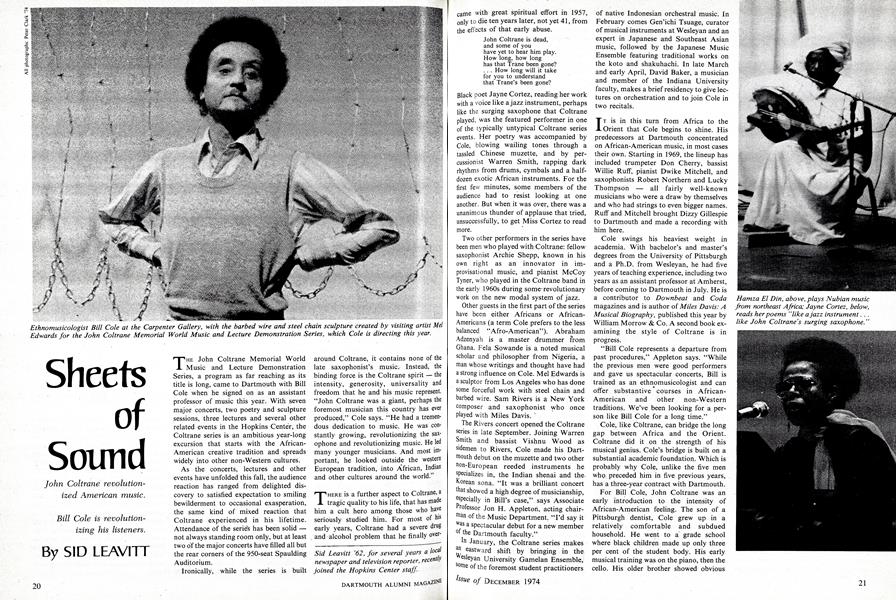

Ethnomusicologist Bill Cole at the Carpenter Gallery, with the barbed wire and steel chain sculpture created by visiting artist MelEdwards for the John Coltrane Memorial World Music and Lecture Demonstration Series, which Cole is directing this year.

Hamza El Din, above, plays Nubian musicfrom northeast Africa; Jayne Cortez, below,reads her poems "like a jazz instrument...like John Coltrane's surging saxophone."

Mel Edwards and his barbed wire and steel chain sculpture created for the Cole Series.

Above, from left, Bill Cole, poet Jayne Cortez, and visiting artist Mel Edwards; below,Cole and percussionist Warren Smith accompany Cortez as she reads her poems inSpaulding Auditorium as part of the year-long series commemorating John Coltrane.

Above, from left, Bill Cole, poet Jayne Cortez, and visiting artist Mel Edwards; below,Cole and percussionist Warren Smith accompany Cortez as she reads her poems inSpaulding Auditorium as part of the year-long series commemorating John Coltrane.

Sid Leavitt '62, for several years a localnewspaper and television reporter, recentlyjoined the Hopkins Center staff.

John Coltrane is dead, and some of you have yet to hear him play. How long, how long has that Trane been gone? ... How long will it take for you to understand that Trane's been gone?

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureDartmouth De Gustibus: More Food for Thought

December 1974 By JOAN L. HIER -

Feature

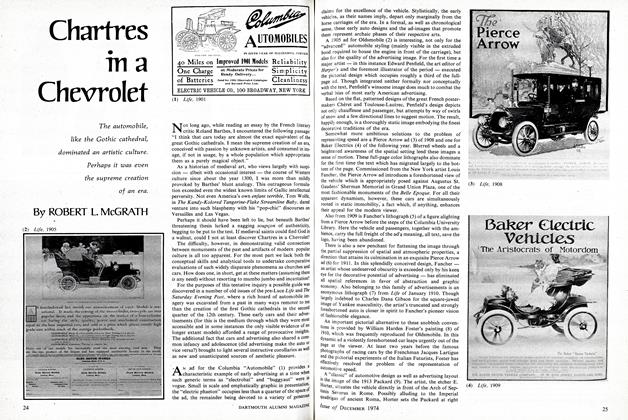

FeatureChartres in a Chevrolet

December 1974 By ROBERT L. McGRATH -

Feature

FeatureOur Crowd

December 1974 -

Article

ArticleBig Green Teams

December 1974 -

Class Notes

Class Notes1949

December 1974 By PAUL WOODBERRY, CHARLES S. KILNER -

Article

ArticleJAMES BRIAN QUINN

December 1974 By R.B.G.

Features

-

Feature

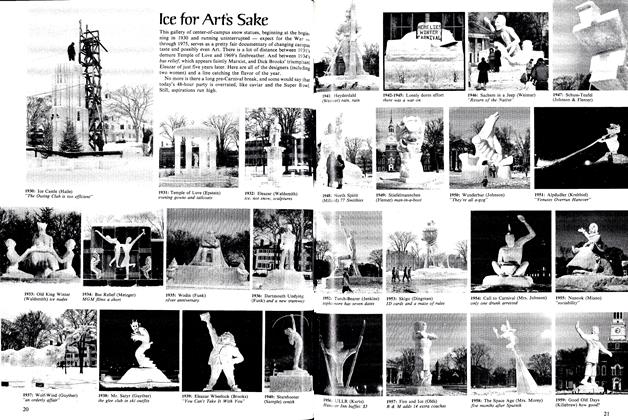

FeatureIce for Arťs Sake

February 1976 -

Feature

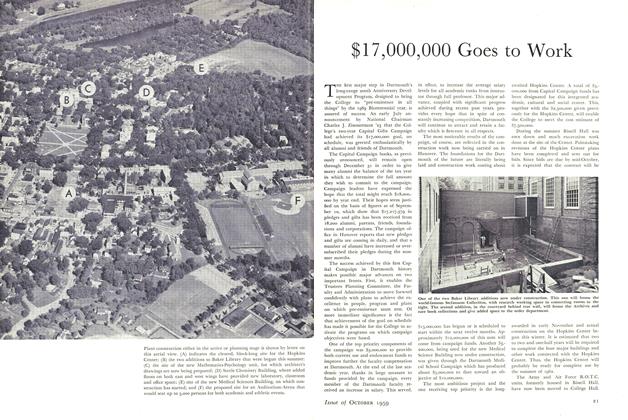

Feature$17,000,000 Goes to Work

October 1959 By CLIFFORD L. JORDAN '45 -

Cover Story

Cover StoryTHE THIRD WORLD'S LOW-KEY CRUSADER

JUNE 1990 By Jay Heinrichs -

Feature

FeatureTo Make What's Good Better

February 1951 By R. L. A. -

Feature

FeatureWhat It's All About

FEBRUARY 1968 By Robert B. Reich '68 -

Feature

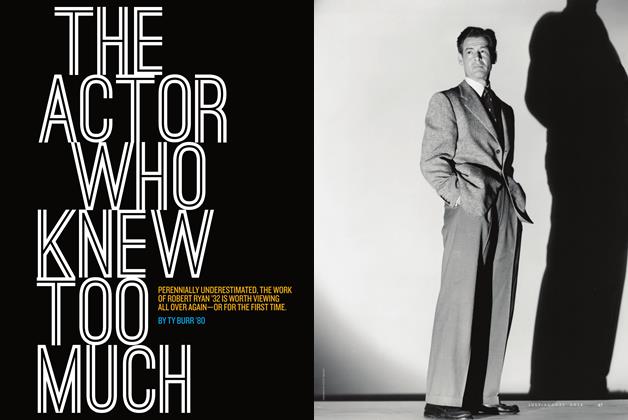

FeatureThe Actor Who Knew Too Much

July/August 2012 By TY BURR ’80