Commissioned more than 2,000 years ago, the Assyrian reliefs today are grouped fully together for the first time since they came to Dartmouth more than a century ago. They recently returned from a second major journey - a 10-month stay at the Center for Conservation and Technical Studies at the Harvard University Art Museum where they underwent a thorough restoration.

"What you're seeing is something that shows its age, and that's part of the beauty of these pieces," said conservator Richard Newman who, with two colleagues, accompanied the panels from Cambridge back to Hanover to oversee their installation in the Kim Gallery.

"There is nothing wrong with letting a piece like this show its age," said Henry Lie, another of the conservators who worked on the reliefs. "Now they should last indefinitely, as long as the environment is good and as long as they're not touched."

While the traces of time are allowed to remain, removing the traces of past human touches was the bulk of the conservators' work, Newman and Lie said.

For most of their 2,000 years, the panels sat beneath the ground. They were buried in sand and touched by groundwater that wore away much of their once-brilliant paint and left surface etchings. When they were finally unearthed, the work of man began. First, their 12-inch depth was reduced to a thickness of about three inches, and then cut into smaller pieces so they could be transported across the Syrian Desert on the backs of camels.

Initially installed in Reed Hall the Dartmouth reliefs then began more than a century of moves to various display sites around the campus.

Through the years and the moves, the pieces acquired surface dirt and scratches. From time to time, attempts were made to glue them together with cement and other adhesives. Once, someone drilled holes in them, apparently to attach them to a wall. The little paint that remained continued to flake steadily away, and at least once, an attempt was made to repaint them. As the panels were moved from place to place, some of the corners were nicked and small elements of design were chipped away.

"The material is gypsum which is very soft stone-very easily damaged but very easy to carve," Newman said. "There wasn't a lot of care has been taken to protect the stone, but there were no major losses. Most archeological things you see have major losses. These are complete with minor surface losses.

"Much of what we did was to remove what was done in the past, and that is what most conservation work is today. The philosophy of conservation around the world today is to use materials that can easily be removed in any kind of reconstruction or repair."

Most of the surface dirt was loose and easily removed. Using organic solvents and small tools such as hammers and chisels, they also removed all traces of past restoration attempts over-painting, over-filling and chunks of cement and other adherents. The last remaining red and black specks of restoration attempts some only faintly visible-were also removed. In a few places, the conservators reconstructed missing elements of the design. "We want to show the beauty of the piece," conservator Pamela Hatchfield explained, "so we filled in any parts that would detract from the beauty if they were allowed to remain missing-corners, fingers, parts of hands. But we did reconstruction work only in areas where we knew exactly what was going on. We didn't create any designs of our own. We only replaced minor losses."

The conservators also designed and developed the mounting system for the reliefs, using plaster to attach the backs of the reliefs to aluminum Hexel, a honeycomb panel that is light and rigid. The Hexel panels are backed for extra rigidity with hollow-stock iron bars hidden behind the gallery wall surface.

With the reliefs in place, the conservators filled in the century-old cuts and bolt-holes with a plaster-like substance and painted over all traces of the plaster with acrylic paint.

Even with their intricate installation, the reliefs could easily be removed from the wall at any time, the conservators noted. But museum director Jacquelynn Baas said the massive reliefs will stay where they are as long as the building stands. They have, in short, reached their journey's end.

Henry Lie of the Center for Conservation and Technical Studies, ArtMuseums of Harvard University,filling gaps between sections of restored Assyrian reliefs during theirinstallation at the Hood Museum ofArt. Note the intricate supportstructure on the wall.

Richard Newman, another member of theHarvard restoration/installation team,carefully fills in a gap between two largesections of one of the heavy gypsum slabs.

Henry Lie overseeing preparations to lift a section of the newly-restored relief into place. Considering theirage and itinerant existence, they are in remarkably good shape.

Georgia Croft is former arts page editor andClaremont bureau chief for The Valley News and currently a free-lance writer.She has covered many a Hopkins Centerevent.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureFrom "a few curious Elephants Bones" to Picasso

September 1985 By Jacquelynn Baas -

Feature

FeatureCONJUNCTIONS, CONFLICTS & CHALLENGES

September 1985 By Charles W. Moore -

Feature

FeatureJourney's End: The Assyrian Reliefs at Dartmouth

September 1985 By Judith Lerner -

Feature

FeatureDingwall of Dartmouth

September 1985 By Fritz Hier '44 -

Sports

SportsMany Sighs and Many Tears

September 1985 By Jim Kenyon -

Article

ArticleThe Life of the Mind

September 1985 By Dorothy Foley '86

Georgia Croft

-

Article

ArticleFriend of the media

MAY 1985 By Georgia Croft -

Article

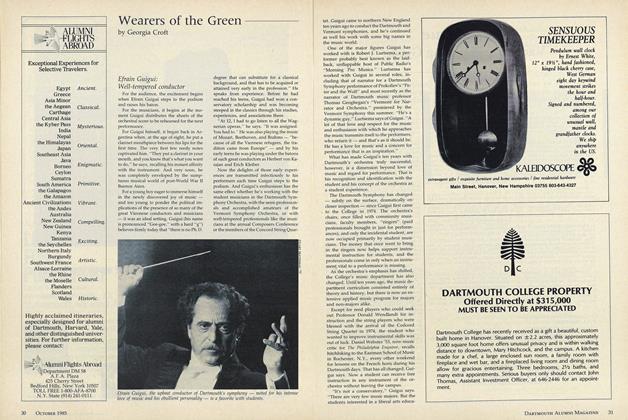

ArticleEfrain Guigui: Well-tempered conductor

OCTOBER 1985 By Georgia Croft -

Article

ArticleConnie Lambert: Doyenne of "The Daily D"

NOVEMBER • 1985 By Georgia Croft -

Article

ArticleMatthew Marshall: Keeper of the Inn

MARCH • 1986 By Georgia Croft -

Article

ArticleGil Fernandez '33: a fine friend to the feathered

MAY 1986 By Georgia Croft -

Article

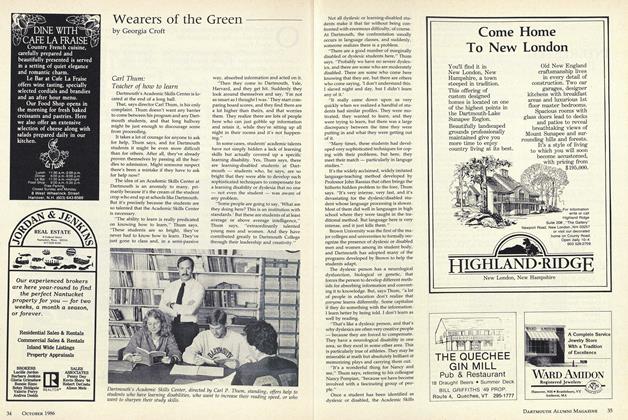

ArticleCarl Thum: Teacher of how to learn

OCTOBER • 1986 By Georgia Croft