"Our fossilized layer cake" STUART M. STRUEVER '53 calls it, the archeological excavation in the lower Illinois River Valley which has shed new light and disturbed old dogma on the life of early man in North America.

It was in 1968 that Struever, Professor of Anthropology at Northwestern University and president of the Foundation for Illinois Archeology, first visited the farm of Theodore Koster, whose plow had unearthed an extraordinary number of Indian arrowheads and broken bits of pottery. There, in a cornfield sheltered from north and west winds by protective bluffs, Struever, with a diverse crew of scientific colleagues, students, and volunteers, has since uncovered 12 distinct horizons of prehistoric communities, dating back - so far - to 6000 B.C. and long antedating Egypt's pyramids and Britain's Stonehenge.

The ancient villages show up on the outer walls of the 120-by- -66 foot excavation as levels of dark organic soil, signifying successive human occupations, neatly interspersed with pale layers of sterile soil. Within the excavation the ground is marked off" in six-foot digging squares, from which the soil is carefully troweled at three-inch levels, its yield of fossils, artifacts, bone fragments, bits of charcoal, and other scraps of prehistoric debris painstakingly separated from the dirt, bagged, and marked for laboratory study.

The "block of focus" for the 1973 field season was an area of nine digging squares by seven, where simultaneously students were uncovering a hearth at Horizon 6 (2500 B.C.), attempting to delineate the thin stratum of Horizon 7, and discovering post holes indicating a house in a series of squares which formed a trench through Horizon 8 (4100 B.C.) A few squares were through Horizon 9 and into sterile soil beneath. Test squares nearby uncovered in 1971 the skeletons of a domesticated dog and an 18-month-old baby ceremonially buried about 5000 B.C. at Horizon 11, 28 feet below present ground level. Extensive excavation of Horizon 11, "the richest and potentially the best preserved community ruin" at the site, according to Struever, and further investigation of Horizon 12 (34 feet down) and below, originally planned for 1973, had to be postponed until a system could be devised and funds raised to lower the water level.

The goal is not the retrieval and preservation of museum art - Koster surrenders no gold masks, no jeweled sarcophagi, no priceless scarabs - but something less dramatic but far more fundamental. "That new archeology," as Struever puts it, "is attempting to understand how man copes with his environment, alters his environment, and how environment affects man."

"In the past," he writes, "archeologists have tried to trace and describe events in the history of prehistoric groups. The new archeologist tries to explain them. Instead of just listing historical events, he seeks the underlying causes that link them.

... We may ask, for example, if there are universal prerequisites to warfare in human history. Must certain conditions exist before large-scale conflict begins, and what sets these forces in motion? We have found no evidence of warfare in the Illinois River Valley until about A.D. 800. Our problem is to discover why warfare started then and why man lived there peacefully before that time."

A multi-discipline team of scientists pursues the "new archeology" in the natural field laboratory of Koster. Geologists study the soils and malacologists snail remnants to learn about climatic conditions of each horizon. Zoologists examine bone fragments to assess protein intake. Botanists find evidence of man's knowledge of domesticated plants as early as 800 B.C., but none of his systematic use of that knowledge for more than a thousand years. Chemists study artifacts for components of their manufacture, tracing the origins of source materials to map prehistoric trade routes. Biologists learn from skeletal remains the incidence and prevalence of man's diseases through the millenia. Computer experts design programs to store, codify, and retrieve the myriad items of information which accrue.

Their help comes from many sources. A carpenter from Missouri holds workshops on making stone tools, reproducing the processes by which ancient man manufactured his implements to recreate the patterns of ancient communities. A professional engineer and amateur photographer spends his vacations recording the work on film. Corporations donate equipment, and local farmers sides of beef to feed the crews. Mrs. Struever, an archeologist by experience if not academic training, whom Struever met when she was at Colby Junior College, has developed laboratory techniques, runs the supply shed, pitches in with the cooking, and lectures on the program during winters in Evanston. The Kosters, who have cheerfully donated their corn-field, provide hot and weary diggers with a shady lawn and a cool drink from the well.

Undergraduates and pre-professional graduate students, older adults, high school and junior high pupils enroll in the Northwestern Field Schools to learn science by doing it. Living in makeshift quarters and working in makeshift laboratories in the flood-ravaged town of Kampsville (pop. 450), ferrying across the river to reach the Koster site nine miles away, some 120 students, aged 12 to 74, worked last summer with the professional staff, digging and scraping, sifting and washing, classifying and analyzing the vestiges of early American civilizations.

Although he has always thought of himself primarily as a researcher, Struever finds the educational program ever more engrossing. "The key phrase is 'participatory education. Archeological excavations are one of the most effective means of bringing students face-to-face with the world of ideas." He attributes the high level of student motivation and performance in the program to "the recognition that it is he, the student, who is responsible for recovering the data on which the Koster archeological history will be built." For many, he notes, working at what amounts to the academic commune of Koster provides "their first experience in a role that requires more than the activities of self-development," their first "realistic picture of the scholar and the scholarly process."

The site is not the oldest in North America - or even among the 750 prehistoric communities estimated to exist in the region - but it has special value, Struever explains, "because it represents 12 frozen pictures of 12 separate human attempts to get along in the environment with available culture. With ail 12 horizons located in one spot you have, in a sense, almost a stereopticon picture. If you flip through the individual pictures fast enough you see some motion ... a kind of chronicle of the human endeavour to survive in Midwestern U.S. over a 7000-year period."

Data from Koster has raised new questions and shaken widespread assumptions. Evidence of permanent dwellings at Horizon 8 indicates stable communities 6000 years ago, exploding the theory that man was a nomad until he was an agriculturalist. Koster has shown that, contrary to the view that survival demanded all prehistoric man's time before he domesticated animals and crops, ancient hunter-gatherers in the rich Illinois Valley probably enjoyed more leisure than industrial man. project scientists ponder the causes of war, the means by which Koster man achieved zero population growth for thousands of years before a burst of numbers about 100 B.C. disturbed the equilibrium, the reasons for a high incidence of chronic arthritis observed in skeletons from the Horizon 6 cemetery, why inhabitants periodically abandoned Koster, and their destinations when they left.

Struever finds the role of fund-raiser intruding increasingly on those of researcher and educator as he and his colleagues seek answers for these questions and countless others. As head of the Foundation for Illinois Archeology, a clearing-house for contributions which shares support of the project with Northwestern University, he writes and lectures extensively on the program's needs. Despite nation-wide publicity, funding comes hard. "If you tell people you need money for excavating in Iran or Peru, they think it's exotic; mention southern Illinois and their eyes glaze over," he says.

There is a sense of urgency among the staff to learn all they can from Koster man's struggle to survive before the road graders and the bulldozers roll out their concrete carpets for a sprawling St. Louis suburbia, obliterating forever Struever's layer cake of civilization with its lessons for man's struggle to survive in the future.

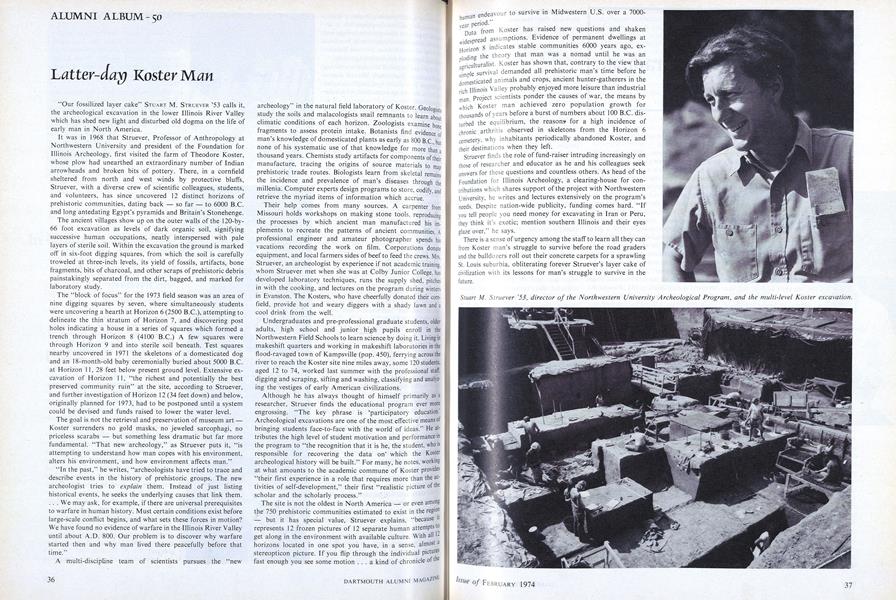

Stuart M. Struever '53, director of the Northwestern University Archeological Program, and the multi-level Koster excavation.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

Feature‘No reason... except faith' Ten Years of ABC

February 1974 By BRUCE KIMBALL -

Feature

FeatureIn language teaching, a call for ‘madness'

February 1974 By R.B.G. -

Article

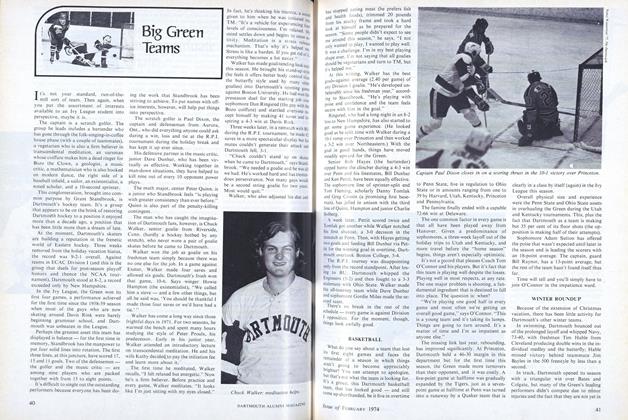

ArticleBig Green Teams

February 1974 By JACK DEGANGE -

Class Notes

Class Notes1950

February 1974 By JACQUES HARLOW, ERIC T. MILLER -

Article

ArticleHEINZ VALTIN

February 1974 By Andrew C. Vail Memorial, R.B.G. -

Article

ArticleThe Undergraduate Chair

February 1974 By DREW NEWMAN ’74

Article

-

Article

ArticleTHE WYMAN TAVERN AT KEENE, NEW HAMPSHIRE

March 1920 -

Article

ArticleDR. HOPKINS KEEPS SEVERAL IMPORTANT SPEAKING ENGAGEMENTS

January, 1925 -

Article

ArticleTuition Raised

DECEMBER 1958 -

Article

ArticleVox in the Box

March 1998 -

Article

ArticleDiary of a Freshman

March 1933 By A. P. Butler '36 -

Article

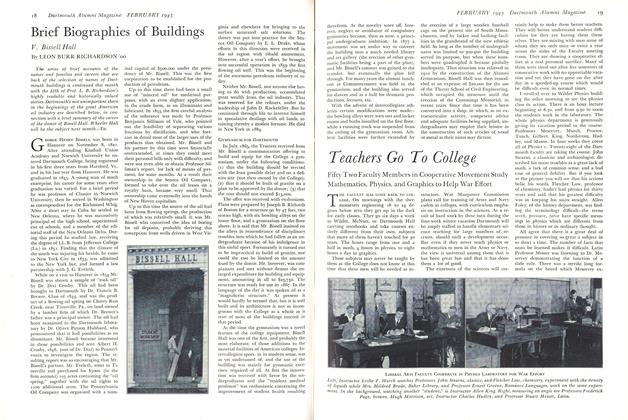

ArticleBrief Biographies of Buildings

February 1943 By LEON BURR RICHARDSON '00