By Lawrence G. Hines, Professor ofGovernment. New York: W.W. Norton &Co., 1973. 339 pp. Hard cover, $9.75;Paperback, $3.25.

At any given time and place, society's operative goals (as differentiated from its more noble stated goals) are merely the collective objectives of the most aggressive humans in control of a certain piece of territory. The Ship of State is filled with those unwilling or unable to manipulate, captained by those drawn or driven to manipulation.

If we accept the premise that the future of the environment is vitally keyed to the actions of corporate managers too often environmentally callous or ignorant, it becomes crucial to impart an environmental sensitivity to these masters of our fate, and to the ranks of replacements moving through our colleges and graduate schools.

Many books are written. Some authors contend that any attempt to define environmental "right" or "wrong" in terms of Man's paper system of buying and selling is self-serving, delusional, and ultimately meaningless. Others, ecologically sensitive though admirers of the market system, strive to sell ecology to the businessman. Their strongest technique is the effective identification of dollar value that has been displaced or ignored. Once the market system can assign a dollar cost to an item, it can deal with it.

While Professor Hines' outlook tends toward the latter, his writing exhibits sufficient environmentalist ambience to create a stimulating tension which he wisely does not resolve.

Although he rarely reveals his personal reaction to an issue, seems to consider natural things primarily as resources available to man, and writes somewhat unevenly, Hines is clearly not among those who publish to nourish on the withering tit of environmental concern. His close and interested observation of the relationships between environmental and market systems is apparent.

The book is most compelling in a series of chapters on population, economic growth (containing important comments on growth vs no-growth), the market economy and benefit-cost analysis. The author is an economist and his writing in these chapters is clear and confident.

Subsequent chapters (energy, water pollution, air pollution, solid waste, the future) are subtly paler. The presentation of facts continues apace, but with perceivably less focus.

Disturbingly, Hines seems complacent about the inexorable depletion of the earth's petroleum. He is confident that plenty of oil is left and to all appearances unbothered by the escalating consumption of an irreplaceable commodity, as if it does not matter that once it's gone, it's gone for good. As in the ecosystem, ironically, in this economic system the fiscally hardy resource moves into a niche made available by the fiscal weakening of another resource. The fullness of the niche becomes all-important; the fate of the depleted resource is not.

Environmental Issues is a wide-ranging introduction to these issues which the nonconversant would do well to read.

A freelance graphic designer Mr. Sheaff hasheld positions in several New Hampshire environmental organizations.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureJournal of a Long Season

March 1974 By TOM EGGLESTON -

Feature

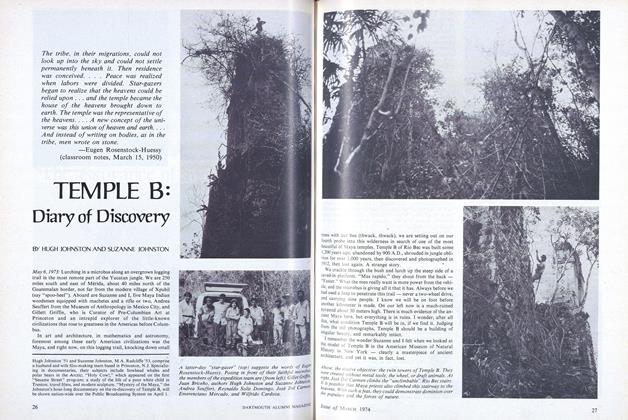

FeatureTEMPLE B: Diary of Discovery

March 1974 By HUGH JOHNSTON AND SUZANNE JOHNSTON -

Feature

FeatureConduit for the Faith)

March 1974 -

Feature

FeatureDelivery Man

March 1974 By M.B.R. -

Feature

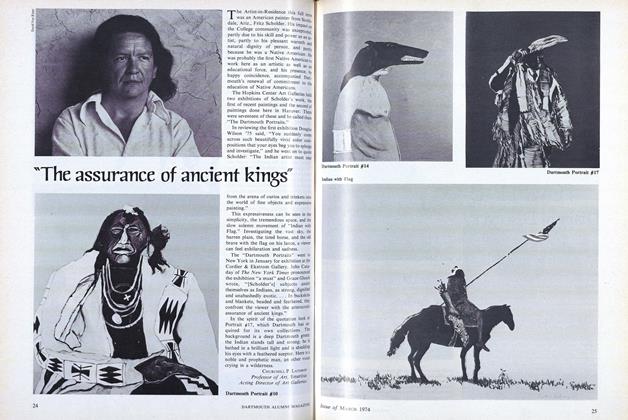

Feature"The assurance of ancient kings"

March 1974 By Churchill P. Lathrop -

Article

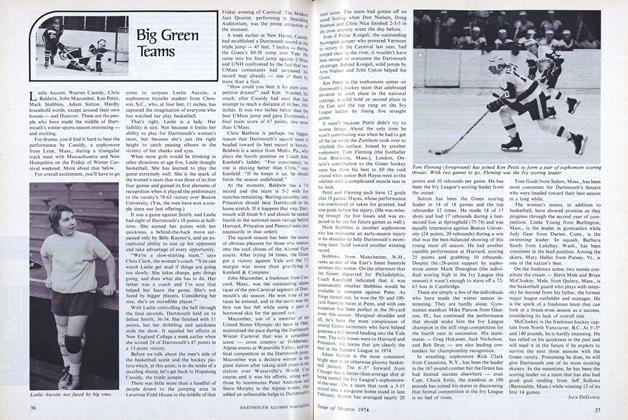

ArticleBig Green Teams

March 1974 By JACK DEGANGE

Books

-

Books

BooksFaculty Publications

June 1929 -

Books

BooksShelflife

Jan/Feb 2006 -

Books

BooksPETER HARRISON, FIRST AMERICAN ARCHITECT

July 1949 By Hugh Morrison '26 -

Books

BooksJ. RAMSAY MACDONALD

January, 1930 By L. H. Evans -

Books

BooksINTRODUCTION TO BUSINESS

March 1948 By Nathaniel G. Burleigh '11 -

Books

BooksMACHINE REPLACEMENT FOR THE SHOP MANAGER.

May 1962 By PROF. GEORGE A. TAYLOR