Planning to give the little nipper a gift of reading from the good old days? Don't.

ONCE upon a time, my happiest memories were made of books, particularly those small, spring-colored volumes I read as a child. Like oatmeal on a cold winter's morning they stuck with me even as I trudged over the hills and far away. The days when I tumbled scratchless through the briar patch with Brer Rabbit or humped fiercely over the handlebars of my tricycle and pedalled wildly along sidewalks like "Toad the terror, the traffic queller" once seemed forever golden. Later, when getting and spending edged into my consciousness and I wanted more than the sum the orthodontic fairy left under my pillow, I opened a neighborhood "store" and like Ginger and Pickles did a thriving business for a day or two in lemonade and curiously speckled cookies.

From across the bar of time, those cookies and that lemonade, so sourly sugared by flying, buzzing things, glimmered like milk and honey - at least they did until last summer, when Dartmouth and the National Endowment for the Humanities linked checkbooks and air mailed me to the British Museum for a sabbatical year. Nestling down in the Reading Room like cheery old Horton on the egg, I naively decided to study 18th century English children's books. Here, I thought, I would be able to amble down a country lane like that of my childhood, where the trees were sure to be all evergreen and the blown breezes jasmine sweet. Alas, like a drinking man's dream of fair women, the harsh daylight of research brought tawney Betty Lou with hairbrush in hand and not the fair Ophelia.

At the beginning of the 18th century, there were few books in print which were published specifically for children. Such books as to be found were written mostly by divines, and I began my studies with these, fully expecting to find the faith of my fathers comforting still. Seeing the unsaved child as the father of the demonic man, these books, I soon discovered, single-mindedly preached damnation. "Now we look to the preventing of evils," Hezekiah Woodward wrote in Of TheChild's Portion in 1649, "which while they are but in the seed may be crushed, as it were, in the egge, before there comes forth a flying Serpent or Cockatrice." Few children became cockatrices or flew hissing through the heavens in 1649, but it is doubtful whether this happy state of infancy resulted from the efforts of Woodward and his fellow laborers in the vineyard. What seems more probable is that such books shook many a child's frail "clayey tenement" and contributed to his early promotion to glory.

In A Token for Children James Janeway urged Satan's Brat" to read his book over an hundred times." Then when the "pretty Lamb" began to weep, he ought, Janeway preached, go into his garret, fall upon his knees, "weep and mourn," and beg Christ for "Grace and Pardon," pleading with Him to make "thee his Child. A certain "beggar boy," Janeway recounted, seems to have done just that. While he curled through alleyways as a "Bough from old Adam's Seed," the young beggar was robustly healthy. Taken into service, however, he was happily transformed by Grace; within a short time, his "Self-abhorrency" grew so great that "he could never speak bad enough of himself' and the only "Name he would call himself' was "Toad." Not surprisingly, it was not long until Toad was "received into the arms of Jesus." With Janeway's Rock of Ages lashed firmly to their backs, children seem to have had difficulty swimming through this Vale of Tears.

As the flowers along my path now hung like veined lilies and the trees squatted like yews, I fled the rocky wilderness of religious books, and with relief began reading chapbooks. In the first decades of the 18th century, chapbooks became the most popular kind of children's fare in England. Usually measuring four by six inches and consisting of 24 pages, chapbooks were published unbound and were printed on rough rag paper. Illustrated by crude woodcuts, they were distributed throughout Britain by hawkers who bought large numbers and sold them for a penny or twopence apiece.

Through chapbooks, Lilliputian readers made their first acquaintance with Perrault's "classic" fairy tales: Sleeping Beauty, Little Red Ridinghood, Bluebeard, Puss in Boots, Diamonds and Toads, Cinderella, and Hop o' my Thum. Like that odd menagerie, however, which sailed with the Bellman in search of the Snark, the matter of chapbooks was diverse. Chapbooks were written not only for children but also for the lower and middling classes. And much of the credit for the rapid spread of literacy in Britain can be attributed to their wide distribution and broad popularity. Still, what brought a cherry-red blush to the milk-white cheeks of buxom Chloe or made Strephon snort, guffaw, and then grip his thighs in hardy pleasure was not necessarily suited for Sammy Sweetchild or Little Master Worthy. Chapbook peddlers sold "adult" chapbooks, too. And doe-eyed Margy Meanwell sitting demurely before the grate was just as like to be studying the amorous adventures of "Wanton Tom," who got 16 maids with child in as many weeks, as she was the romantic swashbuckling of Guy ofWarwick, Hector Prince of Troy, or TheSeven Champions of Christendom.

In 18th century chapbooks, little Jack Horner was not the shy lad we now associate with corners and Christmas pie. Only 13 inches high, he was a rambunctious scalawag who delighted in upsetting his mother's cook, "lusty Joan." Having started a fight by stealing some of Joan's new bread, he darted under Joan's skirts. There he "strait way" seized "by both his hands her beauty spot." When he gnawed her behind her knees, Joan, somewhat understandably, "pist upon his head, and put out both his eyes." Not daunted by rough treatment, this little David then tipped Joan over and bit her "by the arse" until the female Goliath promised never to correct him again.

With my gentle amble through children's books fast becoming a salacious swagger, I hot-footed it away from Jack's corner. And with visions of Hobbitts and Doctor Doolittle dancing through my head, I picked up the chapbook history of The Foreign Travels of Sir JohnMandeville. Containing An Account ofremote Kingdoms, Countries, Rivers,Castles, etc. Together with a Descriptionof Giants, Pigmies, and various other People of odd Deformities. Master Jemmy Gadabout would certainly have been intrigued by Mandeville's account of men with lips so large that they covered their faces when they slept or by the people who had no heads but whose eyes were in their shoulders and mouths in their breasts. But I shudder to think what Jemina Placid's reaction was to the inhabitants of an island near India. It is "so warm" here, Mandeville reported, "that the men's members hang down to their shins." Lest sensitive travelers avoid the island, Mandeville reassuringly noted that the natives "of better breeding" concealed their endowments "by tying them up."

BY 1750 or so - not long after Mandeville's travels - British educators and parents had almost universally accepted John Locke's educational theories, and as a result chapbooks plunged from critical favor. Nine men out of ten, Locke taught, were formed "Good or Evil, useful or not, by their Education." "The little, and almost insensible Impressions on our tender Infancies," he wrote in SomeThoughts Concerning Education, "have very important and lasting Consequences." What was once thought high-spirited bawdiness now no longer seemed harmless. "The memory," Isaac Watts declared, was "a noble Repository or Cabinet of the Soul" and "should not be filled with Rubbish and Lumber." "Something more innocent, more solid and profitable" ought, he thought, to be invented. The search for something more profitable led to the moral or instructive tale as parents in "the middling stations of life" become convinced that childhood reading made not merely the moral but also the economic man. Consequently a large market for children's books developed, and by the last quarter of the 18th century, publishing books for children had become an important branch of the book trade with a score or more publishers devoting much of their energies to this "fair seed time of the soul."

Bending the narrative twig to produce proper behavior in a child has always been chancy. Moreover, having now had my literary expections twice scarred, I approached the moral tale hesitantly. Still, it is hard to keep a jack-in-the-box romantic down and as I thumbed my first moral tale, up popped the dream of recapturing that moment of splendor in the grass when Daddy Long Legs pranced smilingly under the "Daffy-down-dilly" new come to town. In many of the instructive tales published late in the century, children were taught kindness to animals. If the father of the man (the child) treated animals humanely, so the reasoning went, then the man himself would treat his fellow men kindly. Unfortunately, what was high seriousness in 18th century theory often turned out to be low foolishness in narrative practice. In The Life and Adventures of a Fly, when the hero became stuck in a jar of honey, Jack Lovebook spooned him out carefully, explaining to his father: "Perhaps, papa, this poor fly has a father, or a mother, or a brother, or a sister, who would have been grieved even to death, had he not returned to them. May we not venture to imagine that he was on his way to visit and comfort some uncle, or cousin, or friend in sickness or distress; and that he might dip into the honey only to carry with him a little load that might make a meal for some sick fly." Later when this aerial Humpty Dumpty tumbled into a milk jug, Sukey J. refused to kill him, explaining that "God Almighty" would not want her to be so cruel "to a poor innocent fly." Instead she stroked him "with a little feather," then cuddled him "upon her bosom" until "the kindly warmth of her little heart" restored his health.

Few of us would relish the return of the bad old times when man had a closer relationship with animals than he does now: when centaurs galloped off with nubile maidens slung across their haunches and Harpies fouled the flowing bowl before the taper of conviviality could be lit. In The History of Little Jack, however, Thomas Day envisioned a world in which the tattered ages returned golden and man was able to lie down with the lion - or with the goat as the case turned out. LittleJack told the story of a foundling who was abandoned on the steps of a tumbledown hut belonging to a decrepit soldier. So poor that he had barely enough barley to feed himself, the old man did not know what to do when he found Jack until he remembered his "one faithful friend," a goat named Nan. Fortuitously, Nan had just lost her kid, and seeing her "utter distended with milk," the old soldier called her to him, and "presenting the child to the teat," was "overjoyed to find that it suckled as naturally as if he had really found a mother." "Gentle Nan" was just as pleased, and "with equal tenderness," she adopted Jack. "She would stretch herself out upon the ground," Day hymned "while he crawled upon his hands and knees towards her; and when he satisfied his hunger by sucking, he would nestle between her legs and go to sleep in her bosom." This delicious harmony lasted for several years until "mammy Nan" died and was "buried in the garden." Not long afterwards, the old soldier turned his face to the wall, and young Jack was forced to seek his fortune. Treading lightly without the burden of a fashionable education on his shoulders, he survived being marooned on the desolate Cormo Islands, thrived as a prisoner of the Tartars on the incipient Empire's eastern border, and eventually returned to Britain to become "one of the most respectable manufacturers in the country."

Among the most popular kinds of children's books in the mid- and late 19th century was the gift book. Presented to budding girls by observant aunts from the country, it consisted of selections of prose and poetry, all of which, like "Excelsior," pointed onward and upward to the realms of heavenly and domestic bliss. Fifty years earlier, gift books pointed in odder directions, particularly when animals were involved. In his Ballads, William Hayley quaintly celebrated the virtues of Lucy's Fido. When Edward, "the monarch of her breast," was posted to India, Fido accompanied him, having been carefully instructed by Lucy to make Edward's "life thy care." Lucy's wish was Fido's command. When Edward planned to swim in a river which swarmed with reptiles, Fido tried to dissuade him. Unsuccessful in his efforts, Fido gallantly jumped into the water before Edward and with a farewell whimper disappeared down the gullet of a hungry crocodile. Fido's leap saved Edward's life, and although Fido was gone, he was never forgotten. Lucy commissioned a statue of him and had it placed in her bedroom. On Edward's return, she and Edward were married, and, Hayley wrote, "The marble Fido in their sight,/ Enhanced their nuptial bliss;/ And Lucy every morn and night,/ Gave him a grateful kiss."

Never again could I drop an innocent tear on the pages of Bob Son of Battle or let The Hound of the Baskervilles send a pleasant chill up my spine. Like a Trojan dog, Fido slipped into my unconscious. From his marble sides crept destroyers of childhood's happier times. No more would "Oh where, oh where has my little dog gone" simply lead to "Oh where, oh where can he be." What, I wondered, provoked that violent canine laughter when the cow jumped over the moon? And why did Uncle Wiggily Long Ears stop his car and nibble on its turnip steering wheel? In a world in which goats nursed the future giants of industry, little girls massaged flies, and marble dogs stood guard over hymeneal rites, there obviously could be no genteel answers. And sadly I condemned children's instructive animal stories to that region of chapbooks and darkness visible. Henceforth, I thought, the closest I would come to an animal would be an animal cracker. But even this, the 18th century soon taught me, was dangerous.

AT the beginning of the 1700s, the few children's books that there were stressed that religion was the one thing necessary for life. Since large numbers of children died in infancy, life meant eternal life. In hopes of providing enough spiritual food to enable the young transients to write their names on the heavenly stair, children's books taught cram courses in religion. As the century passed, however, more children began to survive the rigors of infancy, and a shift occurred in the subject of children's books. Emphasis began to be put on food for the body rather than nectar for the spirit. Religion remained an important topic of children's books, particularly in books written for children from the lower classes. But as children now had the leisure to grow religious, it was not pounded home with its former fervor. Typically, The Pretty Play Thing included a section entitled "Maxims for the Improvement of the Mind." Although the maxims began with the head, like Middle Bear's porridge they quickly sank to lower, more vital regions, warning that "he who is always feeding shall soon make a Harvest-home for the Worms."

In her Easy Lessons For YoungChildren, Sarah Trimmer told the sad story of Miss Page, who grazed upon sweetmeats until she foundered. In frightening the age's Little Miss Muffets away from sweetmeats, Mrs. Trimmer was actually a kindly spider. Her particular emphasis on care of the teeth appeared in many children's books and becomes understandable when one realizes that "Teeth" killed strikingly large numbers of people in the 18th century. In a typical week, January 6-13, 1759, 514 people died in London. Teeth killed 26, while among the others consumption killed 91; dropsy, 18; measles, 15; smallpox, 27; and old age, 63. In those days you were not what you ate. But if you ate wrongly, you were not. Even Tom Thumb climbed to the pulpit and spoke out against sweets.

A man of many unique culinary experiences, Thumb's advice was not to be taken lightly. He had as a youth, you may recall, been baked into a suet pudding, eaten by the Red Cow who "turned him out in a Cowturd," and swallowed by a giant who disgorged him "at least three miles into the Sea" where as soon as he splashed down a fish gobbled him up. Like that of Jonah in the whale, this dietary ordeal proved the making of him, for his finny jailer was caught and fortunately brought to King Arthur's table where Thumb was released to the amazement of all the gathered boast of heraldry. Accepted as "his Highnesse Dwarfe," Thumb became a self-indulgent courtier and journeyed about in a grand walnut-shell coach, drawn by "foure blew fleshflyes." Worse yet, he became a great favorite with "Gentlewomen" and amused himself by tilting "against their bosoms with a bul-rush."

By the end of the century, however, Thumb had thankfully reformed, and in Tom Thumb's Exhibition, he mounted a show of the "surprising Curiosities" which he had collected during his travels. Tom did not exhibit his bulrush, but he did show his "wonderful optic Glass" which made all objects viewed through it "appear in such a form as is most suitable" to their "natural qualities or probable effects." Mr. Soberman used it, Tom related, to great advantage to cure his son Jacky "of a most bewitching, and indeed dangerous relish, for sweet tarts and fulsome custards." Thinking that these "luscious geegaws" would ruin Jacky's health "and lay a foundation for some violent destructive disorder," Mr. Soberman borrowed the glass. "After setting out a table in the best parlour with the richest pies and tarts, and with the greatest dainties which could be procured in the pastry way," Mr. Soberman told Master Jacky that he could eat all he wanted after he looked through the glass. Jacky grabbed the glass eagerly from his father, Tom recounted, "but when he looked through it, and instead of pies, tarts, and custards, saw the table covered with ugly toads, newts, and scorpions (for that is the appearance it will always produce in such cases) he screamed out with great violence and ran out of the room immediately."

THIS past spring a thinner, grayer me walked out of the British Museum and into the honking world of Bloomsbury. Like Horton, I had hatched an egg, but it did not turn out exactly as I had planned. Still it is better to have had a childhood and lost it than never to have had one at all. And what advice, you ask, do I have for parents whose children are bursting their swaddling clothes and beginning to lisp in numbers? Keep them illiterate. But if they must read, let them read nursery rhymes. Even here one must remain sadly vigilant. According to Mother Goose's Melody, that doleful ditty about "Three children sliding on the ice" is "almost as diuretic as the tune which John the coachman whistles to his horses."

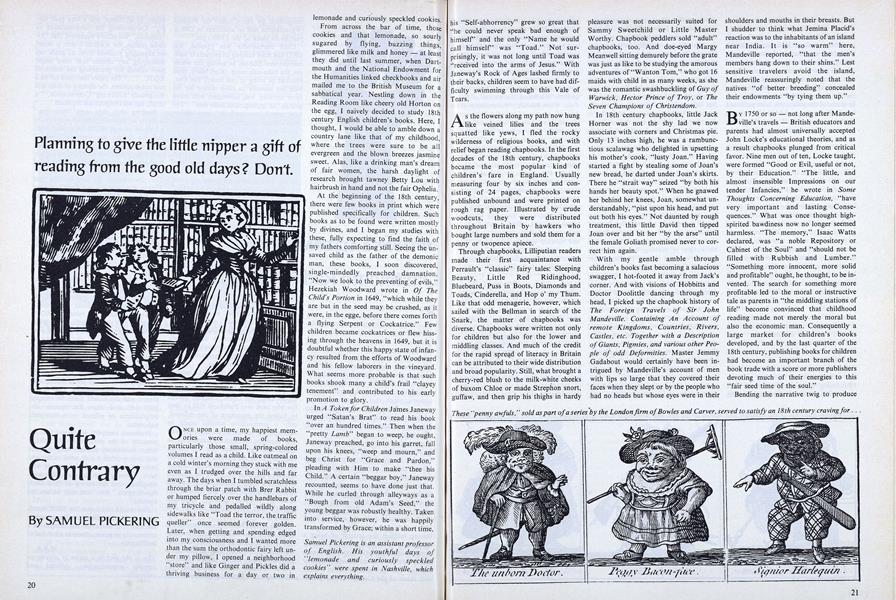

These "penny awfuls," sold as part of a series by the London firm of Bowles and Carver, served to satisfy an 18th century craving for...

These "penny awfuls," sold as part of a series by the London firm of Bowles and Carver, served to satisfy an 18th century craving for...

These "penny awfuls," sold as part of a series by the London firm of Bowles and Carver, served to satisfy an 18th century craving for...

alliteration, poke fun at the manners and morals of the day, and perpetuate some forgettable literary types like Barnaby Cheer-up,

alliteration, poke fun at the manners and morals of the day, and perpetuate some forgettable literary types like Barnaby Cheer-up,

alliteration, poke fun at the manners and morals of the day, and perpetuate some forgettable literary types like Barnaby Cheer-up,

Peggy Bacon-face and her spouse Swillgut. Other themes were patriotic allegory and tooth extraction. The children loved them.

Peggy Bacon-face and her spouse Swillgut. Other themes were patriotic allegory and tooth extraction. The children loved them.

Peggy Bacon-face and her spouse Swillgut. Other themes were patriotic allegory and tooth extraction. The children loved them.

Samuel Pickering is an assistant professorof English. His youthful days of"lemonade and curiously speckledcookies" were spent in Nashville, whichexplains everything.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureThe Assault On Quebec

December 1975 By LEWIS STILWELL -

Feature

FeatureHigh On Your Dial

December 1975 By DAN NELSON -

Feature

FeatureDartmouth Radical Union

December 1975 By M.B.R. -

Class Notes

Class Notes1959

December 1975 By DOUGLAS WISE, BARRY R. BLAKE -

Class Notes

Class Notes1950

December 1975 By JACQUES HARLOW, EDWARD TUCK II -

Class Notes

Class Notes1970

December 1975 By STEWART G. ROSENBLUM, MARK A. PFEIFFER

Features

-

Feature

FeatureOur Captivating Compendium

APRIL 1978 -

Cover Story

Cover StoryThe Geography Department

OCTOBER 1997 -

Feature

FeatureDARTMOUTH ALUMNI FUND REPORT

NOVEMBER 1963 By Charles F. Moore, Jr. '25 -

Cover Story

Cover StoryHow to Get to Outer Space

Sept/Oct 2001 By JIM NEWMAN ’78 -

Feature

FeatureDartmouth De Gustibus: More Food for Thought

December 1974 By JOAN L. HIER -

Feature

FeatureWhat It's All About

FEBRUARY 1968 By Robert B. Reich '68