This account, by the late Lewis Stilwell,professor of history at Dartmouth from1916-59, is the second in a series describingpivotal engagements during the Revolution.The assault on Quebec took place inlate December 1775, shortly after BenedictArnold's heroic, if ill-planned, marchnorthward through the uncharted NewHampshire wilderness. After occupyingAspen Point, a few miles from the Citadel,Arnold's tattered force soon linked up withthe troops of General RichardMontgomery, who had taken Montreal inNovember. The prize was all of Canada,and against grim odds - obvious even tothe Americans - the fight was joined in apre-dawn snowstorm on the last day of theyear.

QUEBEC was the front door to Canada. The back door to Canada was Ticonderoga. The Americans had held the back door for six months but the front door was still British. As long as the King's troops held the river citadel, reinforcements could come in by sea, the British Navy could push up the Saint Lawrence to Montreal, and the whole of Canada might be lost.

This was a strategic fact which everyone then. understood. It had been proved dramatically in the last war. General Wolfe had taken Quebec in 1759 in the famous fight on the Plains of Abraham. Then and there the whole of Canada had fallen. It was this memory of Wolfe's success that was in the minds of Montgomery and Arnold as they planned the climax of the Canada campaign.

The same thoughts dominated General Carleton as he hurried to defend Quebec. Carleton had served with Wolfe. He had seen the great mistake made by the French when they came out of their defenses and gave battle to the British in an open field. Carleton would not repeat that mistake. He meant to stay strictly on the defensive.

Carleton was now in Quebec. On that same 19th of November that marked Arnold's withdrawal to Aspen Point, Carleton was passing down the river on the last lap of his escape from Montreal. The guns of the British garrison saluted his return.

Carleton in Quebec was all energy. A line of log palisades was built on the north side and on the south side of the Upper Town. In the Lower Town two sets of barricades were made, closing in each case the narrow pass between the waterside and the high cliff. The wall of masonry that faced the west was repaired and strengthened, and a hundred cannons were taken from the ships or resurrected in the towns and placed where they would count the most.

Carleton at the same time stiffened his personnel. The mixed garrison of regulars, colonials, sailors, marines, and militia was organized in four divisions. Regular watches and patrols were set. The men were to sleep in their clothes ready for instant duty.

American sympathizers were ordered out of the town. By Carleton's proclamation every man who would not fight for England must leave not merely the town but the province by the fourth of December. A little stream of refugees filed out of Quebec to take their chances in the Canadian winter. Some of these men enlisted with the Americans. There was no neutrality or defeatism allowed where Carleton was in command.

The time required for such rush measures had been a present, so to speak, by Arnold to the British. The formal parade of the Americans before the bastions of Quebec had given most effective notice of an intention to attack. After this warning Arnold had withdrawn for two weeks. It was obviously a mistake to give the enemy first a challenge and after that a lapse of time in which to meet the challenge.

Montgomery had meant originally to spend the winter in Montreal. For this safe policy there were two reasons. He faced an acute problem of reenlistment. His troops, like those at Boston, were eight-months' men whose term expired on or about the first of January. But Montgomery, in order to spur on his men, had promised an even earlier discharge. The soldiers, he had said, could leave for home as soon as Montreal was taken. Now that Montreal was taken the promise had to be made good.

Montgomery tried hard to induce reenlistments. A whole new suit of woolens, to be taken from the British stores, was offered to those who would rejoin, together with a reenlistment bounty of one dollar.

Most of Montgomery's New York troops agreed to stay, but the Connecticut men departed in large numbers. The old grudge between the New Englanders and General Schuyler was thus paid off.

Montgomery at the close of November had remaining a total of only 800 men, and even these would need to be reorganized. This was not the best condition for a renewed offensive.

The long, semi-polar winter of Canada had also to be faced. The coming cold might literally kill an army if too long exposed or clad in less than Arctic costumes. The prospect of temperatures considerably below zero is a strong inducement for staying indoors in a well-established town like Montreal.

The winter, moreover, would freeze the waterways. Ships and boats would be unusable. Once the rivers were thoroughly iced over they would become highways for horse-drawn sleds. But there was bound to be a period of weeks in which the ice would be too thick for navigation and yet too thin to carry vehicles. If Montgomery, therefore, were to move against Quebec he must move quickly while the Saint Lawrence was still open, or else he must delay for a whole month until the great river might become a solid thoroughfare.

It was Arnold's predicament that forced Montgomery to move. There he was at Aspen Point in an almost desperate condition. The clothing of his men if new would have been a very shivery protection in Canada; and the clothing was not new, it was in shreds. Arnold's powder was so scarce that Carleton might have marched out from Quebec and forced wholesale surrender without a fight.

Arnold might perhaps have abandoned Aspen Point and pushed upstream himself to Montreal. But Arnold was short of boats sufficient for a water movement, and so many of his men were barefoot that a land march to Montreal would be impossible. Indeed, there is no evidence at all that Arnold even considered such a move. Retreats for any purpose whatever were not compatible with Arnold's temperament.

So it came, to pass that Montgomery moved to the support of Arnold. In three schooners and several batteaux he set forth from Montreal on November 28. He brought with him a supply of powder, a dozen pieces of artillery, a stock of captured British uniforms, and about 300 soldiers.

The expedition reached its goal by a close shave. The British sloop-of-war Hunter had passed up the river above Aspen Point, and Arnold had duly warned Montgomery of its approach. But the fear of being icebound caused the Hunter to withdraw. With a clear river the American boats came through, the ice closing in behind them.

The arrival of Montgomery at Aspen Point, on December 1, was a happy day. The new general outranked Colonel Arnold, and Arnold's troops were favorably impressed. "He is a gentle, polite man," wrote one of Arnold's lieutenants, "tall and slender in his make, bald on the top of his head, mild, and of a fine temper and an excellent general." The boys would follow Montgomery.

The word now was back to Quebec. By December fifth the American lines were reestablished facing the old citadel.

It was an odd-looking army. Most of the troops now were wearing British uniforms, captured in Montreal. This was, of course, quite contrary to the rules of war and made it very hard to tell the difference between the Americans and the enemy. Scarlet, moreover, was hardly the color to wear against a snowclad background of pure white. Some of the riflemen got themselves white "blanket coats" from the local people. But for the most part it was a choice between looking like a redcoat or freezing to death.

Montgomery established a sort of siege line around Quebec. His troops formed a semi-circle from Beauport to Cape Diamond, cutting off land communication with the town. With the river in a semi-frozen state, there was no movement of supplies by water.

This investment of the city had possibilities. The inhabitants and garrison had plenty of food but they were short of firewood. In that climate there was a fair chance that Quebec might be frozen into a surrender in a month or so. The test of the blockade would come when the river became solid and passable. Then the American lines would have to be extended further in order to cut off the supplies of fuel. But Montgomery did not wait that long.

HE first attempted to take Quebec by propaganda. He wrote to General Carleton, promising generous terms for a surrender and terrible destruction if the offer of surrender were refused. Carleton refused even to receive any communication from "rebels." A local woman was then employed to transmit the message. She managed to reach the general's presence only to have her message burned and herself drummed out of town. Montgomery next resorted to Indian arrows shot over the walls and carrying appeals in French and English to the civilian inhabitants. But Carleton had already driven out all pro-American civilians. The American propaganda was a total failure.

Next Montgomery tried his artillery. A battery of six guns was placed within 300 yards of the Saint John gate. There was no possibility of earthworks to protect this battery. The ground was too completely frozen. So the guns were sheltered with a parapet of snow hardened by sprays of water.

An artillery duel ensued. The British used 32-pound shot against the American 12-pounders. The American snow works were an easy target as compared with the British walls of solid masonry. The duel was hopelessly one-sided. After losing several gunners, Montgomery gave up the idea.

Smallpox meantime had broken out. The men were huddled in the close quarters of the local farmhouses. The disease spread. A hundred or so out of the whole force of a thousand were in the hospital. No one knew how many more would be brought down.

There was a reenlistment problem, too, at Quebec as there had been at Montreal. Arnold's troops were eight-months' men, and their term was up on January 1. The 200 riflemen were willing to stay on. They came, of course, from points so far away that they could hardly hope to reach their homes in the dead of winter. But the 400 or so New Englanders were bent on leaving. Winter or no winter the Yankees had had enough of service under Arnold. It was clear that the American force would be reduced by about one-third on New Year's Day.

So Montgomery determined to assault. It was a desperate decision in view of Carleton's thorough preparations. But it seemed to be the only choice remaining. Otherwise the American army hardly could outlast the winter.

The first plan called for a feint attack upon the Lower Town and a main attack with scaling ladders upon the west wall of the Upper Town. This would be difficult enough. Carleton's total garrison was almost twice that of the Americans. The only hope lay in the fact that the British had almost three miles of works to defend and might therefore be surprised at a weak point.

This first plan was carried to the British by an escaped prisoner. So Montgomery made a second plan.

The second plan was even riskier. The feint now was to be made upon the Upper Town and the real attack upon the Lower Town. This real attack upon the Lower Town involved two columns, one on the north side, the other on the south side. The hope was that the two columns would meet at the eastern tip of the Lower Town, and then perhaps be able to push up from that point by a winding road into the Upper Town.

Montgomery determined on a night attack and he further insisted upon waiting for a cloudy, snowy night. With visibility at almost zero the British could not see to shoot, but the Americans could not see where they were going.

The attempt was known to be desperate. Some of the officers wrote out their farewell messages. Montgomery himself prepared one more appeal to Carleton to surrender on the night of the attack, but the appeal was never sent.

The awaited snowstorm came on the night of the 30th, only 24 hours before the New England enlistments would expire. The snowstorm was almost a blizzard.

At about two o'clock in the morning the troops moved.

Two small parties moved - one against the Saint John gate, the other toward the Cape Diamond bastion. These were the fake attacks. They shot off rockets and made a big commotion. The British garrison was alarmed and rushed to man their western battlements.

Thus far the plan worked. The British would concentrate on the west, and would be weak at the barricades in the Lower Town.

General Montgomery led a column of 200 of his New York troops against the south side of the Lower Town. They worked their way down Wolfe's Path through the darkness and the storm. They reached the first barricade and sawed a hole through it. There was not even a single sentry on guard there. They reached the second barricade and sawed their way through that. Not a sign of British resistance.

The little column was by now strung out. The space between the high cliff and the river bank was narrow, and the long, blind march had produced straggling. Montgomery was ahead shouting to "come on."

A blaze of grapeshot came from the windows of a house. British cannon. General Montgomery fell dying in the snow. Several others were killed or wounded.

That was the end of that advance. .Colonel Campbell, who was next in command, took charge of the retreat. Why the retreat occurred, or how, we do not know. There are no records of what happened after the general fell. The British found Montgomery and the other bodies the next morning.

For the other attack on the north side Colonel Arnold had 500 men. The riflemen went first, then the main body of Arnold's New England troops.

They had with them one small cannon on a sled, but the cannon would not fire. The snow had wet the fuses.

Arnold was wounded almost immediately. He was hit in the leg by musket fire from the palisade of the Upper Town. Arnold limped back past his advancing troops and urged them to push forward.

Captain Daniel Morgan was now in command. He was a fighter.

The first barricade was reached and scaled with ease. The British guard was weak. Inside the first barricade Morgan captured a whole British company that was coming to meet him.

The second barricade was also weak. Apparently the gate in it was open, and Morgan was all for pushing on. The other officers were cautious. They wanted to wait for the main body of New Englanders to catch up. So they waited in the darkness in a narrow street hemmed in by houses at the second barricade.

In the Upper Town the British had by now caught on to the pattern of the attack. The Americans on the west, it was now evident, were only feinting. The real attack was in the Lower Town. So British reinforcements were rushed down to meet Morgan at the second barricade.

The fight there was bitter and confused. The American rifles were wet by the snow and would not fire. But the Americans grabbed the muskets of the captured British company and fired them. There was no chance now of directly storming the barricade. The battle shifted to the windows of the houses on either side of the high wooden barrier. In that hour or more in the black and white morning there was no decision.

The British sallied, 200 or more strong, from the Palace gate of the Upper Town. This was a new threat. It put a British force behind the Americans. With another British force in front, a rock cliff on one side and the river on the other side, it was a trap. A few took their chances on the broken river ice and escaped. Most of the rest surrendered.

Over 400 Americans, including more than 30 officers, were taken there between the first and second barricades at daybreak on the 31st of December. Captain Morgan was blazing mad. He refused to surrender to the British, and finally gave his sword to a French priest.

General Carleton that morning had a chance to sally forth and finish off what was left of the American army. But all that he did was send a small force out to take the American hospital. Colonel Arnold in his hospital bed called for his pistols and proposed to fight. But an American cannon, well placed, drove back the British.

The fight was finished, but the siege dragged on. The New England men could not go home now. They were closely locked as prisoners inside Quebec. There were over 100 Americans dead and wounded. The British loss was reported to be under 50. Arnold sent urgent calls to Montreal for further reinforcements. There was still a little hope.

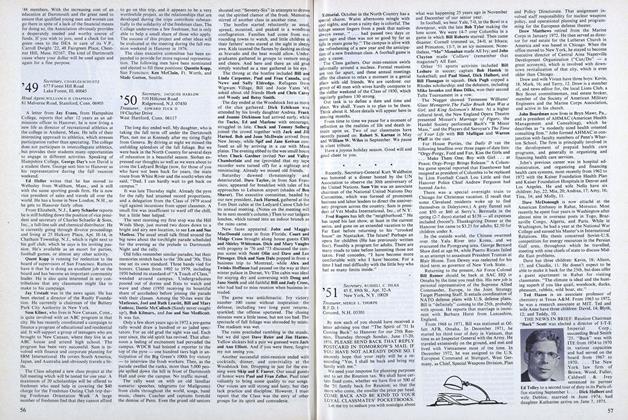

Opposite: several exercises in bearing armsfrom an 18th century British drill manual.

Whatever desperate hopes the Americansheld for victory were dealt a crushing blowwhen General Montgomery was killed inthe swirling snow at the barricades of theLower Town. When the popular officerwas felled by a blast of grapeshot, histroops broke into retreat. Leading anotherattack in the ghostly blackness, BenedictArnold received a painful leg wound andhad to give up his command. John Trumbull."painter of the Revolution" and anaide-de-camp to Washington early in thewar, finished his heroic version ofMontgomery's death in 1788. In the detailat right the general falls into the arms ofhis staff, two of whom were also killed.Above, other American officers - onewould be struck down moments later - recoil from the awful carnage.

The siege was maintained through thewinter, with the opposing armies eyeingeach other warily across the frozensnowscape. On the American side incomingreinforcements were offset bysickness and heavy desertion. Then camethe rumor that 15 British ships had enteredthe mouth of the St. Lawrence, and onMay 5, 1776 the disillusioned invadersscattered for home.

The siege was maintained through thewinter, with the opposing armies eyeingeach other warily across the frozensnowscape. On the American side incomingreinforcements were offset bysickness and heavy desertion. Then camethe rumor that 15 British ships had enteredthe mouth of the St. Lawrence, and onMay 5, 1776 the disillusioned invadersscattered for home.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureQuite Contrary

December 1975 By SAMUEL PICKERING -

Feature

FeatureHigh On Your Dial

December 1975 By DAN NELSON -

Feature

FeatureDartmouth Radical Union

December 1975 By M.B.R. -

Class Notes

Class Notes1959

December 1975 By DOUGLAS WISE, BARRY R. BLAKE -

Class Notes

Class Notes1950

December 1975 By JACQUES HARLOW, EDWARD TUCK II -

Class Notes

Class Notes1970

December 1975 By STEWART G. ROSENBLUM, MARK A. PFEIFFER

Features

-

Feature

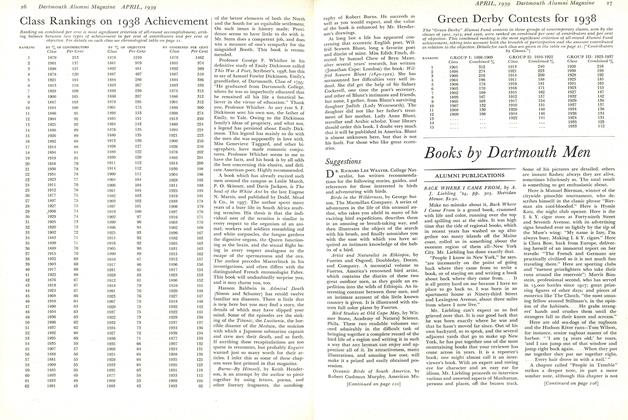

FeatureGreen Derby Contests for 1938

April 1939 -

Cover Story

Cover StoryJohn Ledyard 1776

NOVEMBER 1990 -

Feature

FeatureSailing Dreams and Random Thoughts

MARCH 1973 By JAMES H. OLSTAD '70 -

Feature

FeatureA Day in the Life

Mar/Apr 2004 By JONI COLE, MALS ’95 -

Feature

FeatureOur Place in the Sky

November 1959 By PROF. MILLETT G. MORGAN -

Feature

FeatureThree Staff Members Reach Retirement

JULY 1973 By ROBIN ROBINSON '24