OPTIONS & ALTERNATIVES

RADICAL, it seems safe to say, is no longer chic; it probably isn't even cool. It's a tough, and rather lonely, business being a radical these days, especially on the Dartmouth campus. As one undergraduate observes wryly, "a Dartmouth radical is a Humphrey Democrat."

Hereabouts and otherwhere, the pendulum has swung far back from the days of the late '60s. Whether it be the-end of the war in Vietnam and the draft or the economic pinch that has most students focusing on graduate-school admission and future job security, there's a new mood abroad that some call common sense, some apathy.

Last spring a new campus organization, the Dartmouth Radical Union, was formed in a local effort to swim against the national tide, to revive the social issues that stirred the campus a decade ago. Opposition to ROTC was its major stimulus; its aim is "to provide a continuing forum for the discussion and critique of contemporary social institutions, both in the Dartmouth community and in the society at large, from a radical or left perspective ...." Having fulfilled the criteria of being a legitimately established group, with a duly elected student executive committee and a faculty adviser, with no outside control or funding, with aims deemed not in conflict with those of the College, it has gained recognition by the Council on Student Organizations and an allotment of $200 a year as its piece of the COSO pie.

Until membership was granted, the DRU had been funding its projects in such conventional fashion as selling the whole pie, the bake-sale route. (Karl Marx, thou shouldst be living at this hour!) The first; held last summer to raise money for the farm workers, was advertised with some glee as "an underground bake sale." "The food wasn't very radical," says adviser John Lamperti, professor of mathematics, "but it was good."

The membership of DRU fluctuates with the issue. About 20 or 25 of the faithful make a nucleus, with 100 or so students and faculty members participating at one time or another. Their projects have included gathering and printing information for last spring's Food Day, involvement in the campus appearance of the leader of the People's Bicentennial Movement, and the preparation of a still undistributed "Disorientation" pamphlet, designed as "an antidote" to the unrelieved positivism of Dartmouth's official orientation guides. Among future enterprises are continuing participation in the People's Bicentennial and involvement in the presidential election, concentrating on issues rather than candidates.

The main target of the DRU remains prevention of the return of ROTC to the campus. But where thousands of students milled about the Green, cheering on the few who took over Parkhurst Hall in 1969 to hasten the departure of the military, only a comparative handful could be mustered last month to demonstrate their determination that military training not be restored as an option for Dartmouth students. Even the DRU's tactics mirror the changing times. Instead of strident shouts of defiance, the 50 to 100 students and faculty members clustered around the door of Parkhurst while the Trustees met upstairs, listened quietly, applauded politely, then folded their banners and drifted off.

The Radical Union's most controversial activity this year was picketing Convocation which opened the fall term. Even TheDartmouth, which has exhibited a generally dour stance toward ROTC's return, intoned rather pompously the following day: "Picketing on Convocation Night, of all things, was a very poor tactic." Condemning the demonstration as "tasteless," the editors suggested that "for some reason, the Radical Union is intent on alienating students from its goals and destroying any chance that once might have existed for preventing the return of ROTC. . ." The paper then took off on a real cause célèbre, the absence of cider and doughnuts following Convocation, "a small, but not insignificant tradition...."

Denying that they were "hounding" students at "the only occasion in the entire scholastic year at which the student body and the faculty are together present," members of the DRU took issue with what they saw as The Dartmouth's "editorially hounding the traditions of free speech and assembly." Furthermore, they claimed, "If The Dartmouth defines passing out leaflets, posting signs, and silent picketing as 'pestering' and 'hounding,' then the Bill of Rights is 'tasteless,' too."

Protests against protests - and ensuing protests against protests against protests - swelled the letters columns of The Dartmouth for some time, with one writer suggesting that the editors draw up a list of "Helpful Hints for Tasteful Revolution," complete with tips on "Gracious Guerrilla Garb."

The issue, the DRU maintained, was democracy. The Trustees, wielders of "absolute authority" who "appoint their own replacements in typical aristocratic fashion," had seen fit to reinstitute ROTC in disregard of an 83-7 faculty vote against it and alleged widespread student opposition. Support of ROTC, the group claims, is tantamount to support of "military dictatorships and local elites."

The Jack-O-Lantern contributed its bit of collective wisdom to the proceedings by staging a sit-in at the DRU office, with "non-negotiable demands" that Patty Hearst and the Lizard Lady be released forthwith and that Dartmouth undergraduates be offered more bourgeois experience.

Professor Lamperti speculates that the intensity of the reaction to the DRU's rather modulated protests may indicate that they touched a sore point in the majority of students concerned mainly with such burning issues as cider-and-doughnuts and the revival of "the Dartmouth spirit," but "that may be too optimistic."

Few would claim that the DRU stands much chance of radicalizing Dartmouth in the mid-'70s. Some see the campus as a community at peace, others as a hot-bed of indifference.

This is the first in a series of articles oncampus organizations, official andotherwise.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureQuite Contrary

December 1975 By SAMUEL PICKERING -

Feature

FeatureThe Assault On Quebec

December 1975 By LEWIS STILWELL -

Feature

FeatureHigh On Your Dial

December 1975 By DAN NELSON -

Class Notes

Class Notes1959

December 1975 By DOUGLAS WISE, BARRY R. BLAKE -

Class Notes

Class Notes1950

December 1975 By JACQUES HARLOW, EDWARD TUCK II -

Class Notes

Class Notes1970

December 1975 By STEWART G. ROSENBLUM, MARK A. PFEIFFER

M.B.R.

Features

-

Feature

FeatureHeart Specialist

JUNE 1968 -

Feature

FeatureAlumni Council Report

JANUARY/FEBRUARY 1983 -

Feature

FeatureThe Dartmouth Plan

JANUARY 1972 By C.E.W. -

Feature

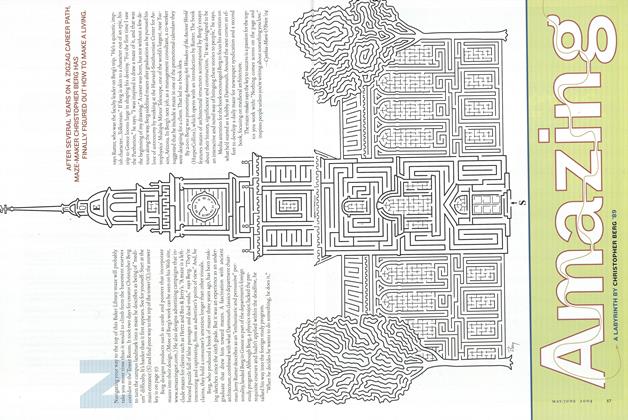

FeatureAmazing

May/June 2004 By Cynthia-Marie O'Brien '04, CHRISTOPHER BERG '89 -

Feature

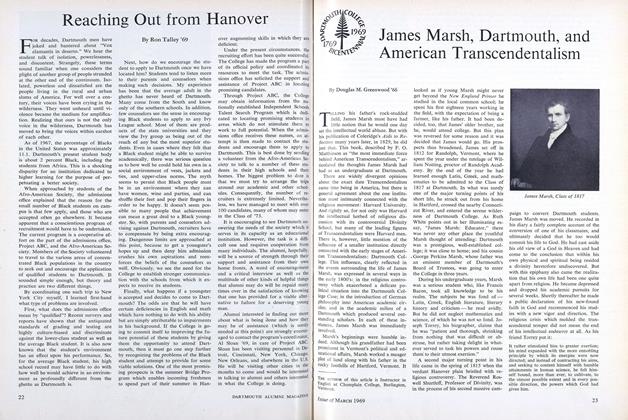

FeatureJames Marsh, Dartmouth, and American Transcendentalism

MARCH 1969 By Douglas M. Greenwood '66 -

Feature

FeaturePOETRY AT DARTMOUTH

MARCH 1963 By RICHARD EBERHART '26