In "Conservation by Conversation" John S. Dickey '29 begins humorously: "The fact that Grenville Clark was a large person in all ways was manifest to anyone who shared a duck blind with him. Physically it was a tight fit, but the conversation was capacious." He is writing in Memoirs of a Man: Grenville Clark, collected by Mary Clark Dimond, edited by Norman Cousins and J. Garry Clifford (Norton, $10).

More seriously, JSD observes that "Grenny's" conversation (it was 1951) quickly focused on the pivotal concern of his life, the development of world peace through world law. His talk on all subjects revealed an abiding faith in the power of education in establishing good human affairs. As a member of the Harvard Corporation, he espoused the cause of academic freedom in the face of strident anti-communism and loyalty-oath measures so hotly espoused after World War II.

After peace through world law, Grenville Clark was most concerned with equal justice for blacks in American society, and as John Dickey had committed himself to this cause in 1947 as a member of President Truman's Committee on Civil Rights, discussion between them centered almost as much on that issue as on international affairs. Clark interested himself in the Dartmouth ABC (A Better Chance) program and hoped to assist blacks in gaining entrance to highly competitive professional schools, especially law schools.

Grenville Clark also made a mighty impression on Stanley K. Piatt '29. When in 1959 Clark descending a narrow staircase in Dublin, New Hampshire, "his great craggy head bent' forward, a massive and impressive figure," he seemed to Piatt "like Moses on the mountain top pointing the way to his promised land." Clark told him that leadership for the United Nations Charter Transformation would be most effective if it came from the smaller nations, because if the USSR proposed it, the United States would oppose it, and the USSR would oppose it if the leadership were centered in the U.S.

In "Grenville Clark and the Uphaus Case," Robert H. Reno '38 tells how Louis C. Wyman, Attorney General of New Hampshire, acted as a one-man legislative "committee" to investigate World Fellowship, a summer camp near Conway, of which Willard Uphaus was director. Because he refused to divulge the names of some 300 visitors to the camp in 1954 and 1955, he was committed to Merrimack County Jail for a year or until he purged himself of contempt. Before the Supreme Court of New Hampshire Clark stated: "I regard the jailing of Dr. Uphaus as a glaring injustice, which is a disgrace to New Hampshire and a discredit to our country." At his own expense Clark tried to get Uphaus's case before the United States Supreme Court, but he lost out. Reno underlines the determination of Clark that a wrong must be righted and that regardless of the odds against him, he was willing to mobilize and finance such an effort.

Discussions about environment, ecology, and pollution have become increasingly hot and complicated. Books have proliferated, some 300. Enrollments in voluntary associations have increased to ten million. With diverse ideas, strong passions, sound and complicated information and unsound and lurid misinformation, the disentanglement of so many labyrinthian threads is a challenge hardly to be solved by a computer. David L. Sills '42 attempts to untie knots in a 36-page essay, highly condensed, in Human Ecology Volume 3, No. 1, 1975, entitled "The Environmental Movement and Its Critics." The bibliography runs to a couple of hundred items. Concluding, Sills asserts that the quality of life in the future will depend on what rights individuals, minorities, and corporations establish to enjoy, protect, utilize, and destroy the environment.

Because of lack of funds, scores of private colleges have closed their doors in the last three years or are on the verge of doing so. Why money for educational institutions is so tight is much on the mind of one of Dartmouth's fund raising experts, Robert J. Finney Jr. '63. Though "crisis" is an overworked cliche, Finney believes that the plight of many or indeed most institutions warrants the use of no weaker word. He gives reasons for the lack of funds: declining enrollments, fiscal mismanagement, rising costs of private education, cutbacks in federal spending, increased number of community colleges, unwise increases of faculty and courses, flagging alumni support, and erosion of the stock market. Finney's ideas and analyses appear in an essay in Reshaping American Higher Education ($3.95), A.M.I. Press, University of Dallas, Irving, Texas 75060.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureThe Battle of Bunker Hill

June 1975 By LEWIS STILWELL -

Feature

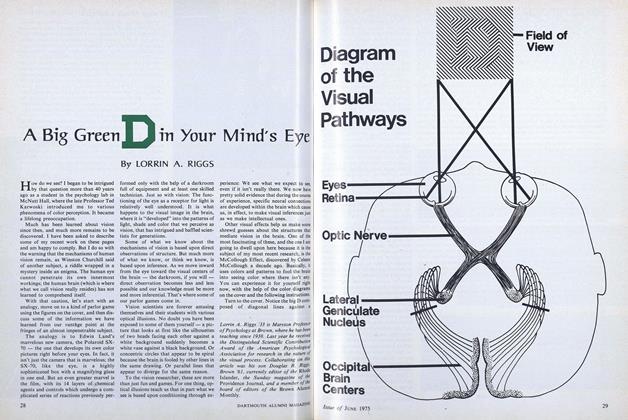

FeatureA Big Green D in Your Mind's Eye

June 1975 By LORRIN A. RIGGS -

Feature

FeatureCommencement

June 1975 By JAMES L. FARLEY '42 -

Feature

FeatureThe Orioles Are Back

June 1975 By DANA S. LAMB -

Article

ArticleBig Green Teams

June 1975 By JACK DEGANGE -

Article

ArticleHonorary Degrees

June 1975

J.H.

Article

-

Article

ArticleJersey Justice

March 1941 -

Article

ArticleFishing in the Land of Vikings

November 1952 -

Article

Article1957 Football Schedule

July 1957 -

Article

ArticleYou Should Be So Smart and Spry as Stan Cobb '03

April 1975 -

Article

ArticleAbout the Artist

Jan/Feb 2003 -

Article

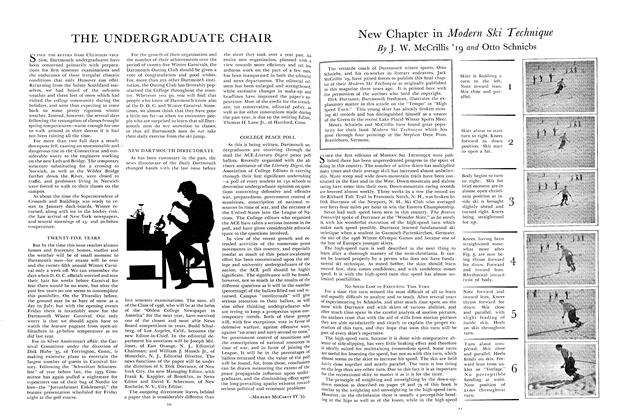

ArticleNew Chapter in Modern Ski Technique

February 1935 By J. W. McCrillis '19 and Otto Schniebs