Reed Browning's biography of Thomas Pelham, Duke of Newcastle (1693-1768), is not only a scholarly and literary event of the first importance, an indispensable work for 18th-century studies, but also a book that can be read with pleasure and indeed excitement by the general reader - a claim that can be made for too few scholarly works. This book calls to mind as comparable J. H. Plumb's great biography of Sir Robert Walpole. Like Plumb, Browning is not only a superb scholar, but an imaginative and graceful stylist.

Thomas Pelham was not one of the great political stars of the 18th century. He does not glitter in the political firmament like the elder Pitt, or Walpole, or even the brilliant but erratic and flawed Bolingbroke. Pelham was constructed of more common clay. But because his personality does not overwhelm his surroundings and provide the focus for all of the reader's attention, his story may actually afford us a better impression of the day-to-day nuts-and-bolts reality of 18th-century politics.

With his enormous inherited wealth, Pelham controlled or influenced a substantial block of votes in the House of Commons. This, com- bined with luck and some agility in maneuver, enabled him to hold high office for almost half a century. He was dominant Secretary of State during one war and First Lord of the Treasury - the 18th-century equivalent of Prime Minister - during another. He was also the most celebrated political boss of his day.

Politics of that era would not have appealed to the gentlemen at Common Cause, but that for me is a large part of its charm. Methods were direct, basic. In the key election of 1722, for example, in which the new Hanoverian political establishment was in some danger because of popular indignation over the South Sea Bubble scandal, Newcastle shored up the foundations of his own power and consolidated the power of the Whig establishment by the simplest of expedients: he bought every vote he could lay his hands on. "For the county elections in Sussex Newcastle spared no expense. His territorial possessions and his governmental patronage assured him of wide influence in Sussex; his readiness to lavish wealth upon an eager electorate assured him of preeminence. His election trips through the country were magnificent processions. A letter from 1722, penned to the duchess, is as revelatory of electioneering as it is of its author: 'I can assure my dear I have thoroughly kept my word with you, for I have been perfectly sober ever since I left you ...' Everywhere he travelled his largesse won him friends." And votes.

Reed Browning writes about the Duke of Newcastle with the kind of objectivity for which the best modern scholarship strives, and also with quiet affection. As a historian, however, he frankly - and interestingly - avows his point of view: "The following prejudices (using that word in its Burkean richness) are the ones I fee] to have been most influential: I am a Christian rather than an agnostic or atheist, a conservative rather than a liberal or radical, a formalist rather than a romantic, a humanist rather than a social scientist." This constellation of attitudes is nowhere intrusive, but I judge it to be pervasive throughout, more as a matter of tone than anything else. Browning is patient with human imperfection, and Newcastle had more than his share. He savors the oddity and unpredictability of life. He has a sense of the pastness of the past, and - perhaps especially where politicians and statesmen are concerned - of the vanity of human wishes.

His Grace, the Duke of Newcastle

THE DUKE OF NEWCASTLE.By Reed Browning '60. Yale, 1975.388 pp. $20.

Mr. Hart, whose newspaper articles aboutpolitics and the American scene are widely circulated,is Dartmouth Professor of Englishspecializing in 18th-century English literature.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureThe Battle of Bunker Hill

June 1975 By LEWIS STILWELL -

Feature

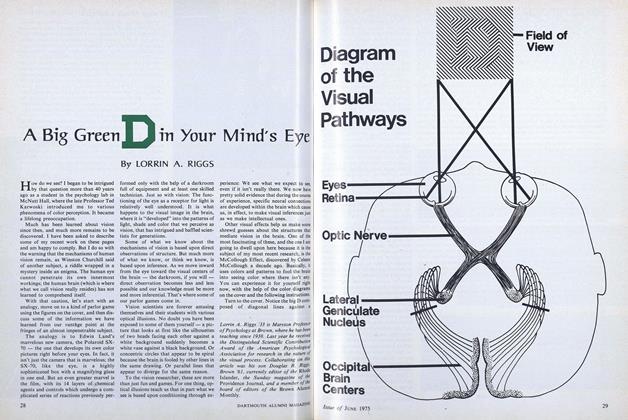

FeatureA Big Green D in Your Mind's Eye

June 1975 By LORRIN A. RIGGS -

Feature

FeatureCommencement

June 1975 By JAMES L. FARLEY '42 -

Feature

FeatureThe Orioles Are Back

June 1975 By DANA S. LAMB -

Article

ArticleBig Green Teams

June 1975 By JACK DEGANGE -

Article

ArticleHonorary Degrees

June 1975

JEFFREY HART '51

-

Letters to the Editor

Letters to the EditorLetters to the Editor

June 1981 -

Letters to the Editor

Letters to the EditorLetters

SEPTEMBER 1983 -

Letters to the Editor

Letters to the EditorLetters

DECEMBER • 1985 -

Letters to the Editor

Letters to the EditorLETTERS

FEBRUARY 1991 -

Books

BooksGODWIN AND MARY: LETTERS OF WILLIAM GODWIN AND MARY WOLLSTONECRAFT.

JULY 1967 By JEFFREY HART '51 -

Article

ArticleGrades Ad Parnassum

MARCH 1978 By JEFFREY HART '51

Books

-

Books

BooksAlumni Publications

January 1936 -

Books

BooksSAGE OF THE SACRED MOUNTAIN.

March 1954 By E. BRADLEE WATSON '02 -

Books

BooksBIBLIOGRAPHY OF TEXAS

March 1956 By HAROLD G. RUGG '06 -

Books

BooksWITHIN THESE BORDERS.

January 1954 By JOSEPH B. FOLGER '21 -

Books

Books* DARTMO UTH OUTING CLUB HANDBOOK.

February 1933 By N. L. Goodrich -

Books

BooksTHE EVOLUTION OF A MEDICAL CENTER: A HISTORY OF MEDICINE AT DUKE UNIVERSITY TO 1941.

NOVEMBER 1972 By WILLIAM L. WILSON '34