Bx Carlos Baker '32. New York: CharlesScribner's Sons, 1969. 697 pp. $10.00.

On trouve au fond de tout le vide etle néant.

—EUGENIE DE GUERIN

Historians, biographers, and other scholarly writers might as well hang on to their manuscripts for the time being. Carlos Baker's Ernest Hemingway is virtually certain to walk off with the major non-fiction prizes this year. And the acclaim will be deserved.

The fact is that this is an awe-inspiring work. It took him seven years to write it - a length of time which seems all too brief when you consider the amount of research the book represents. Toward the rear of the volume a hundred pages of closely printed notes discuss the sources of the information presented in the preceding narrative; these notes, indeed, constitute a sort of second scholarly work, for they contain a good deal of further information about Hemingway. It is clear that this could have been a three-volume work such as the Victorians produced, but that Baker - like Hemingway himself - was ruthlessly selective. Then again, Baker says that he is indebted to "hundreds of men and women" for their assistance and for their recollections of Hemingway. That "hundreds" is modest indeed. At the end of the volume is a list of some thousand people with whom he corresponded or conferred.

This enormous effort to reconstruct a colorful and complicated life has been richly rewarded. Baker has been able to present Hemingway's life in great detail — sometimes, it seems, on a day-to-day basis. "If Ernest Hemingway," he says, "is to be made to live again, it must be by virtue of a thousand pictures, both still and moving, a thousand scenes in which he was involved, a thousand instances when he wrote or spoke both publicly and privately of those matters that most concerned him. ... If all the pictures are not here, there may still be enough of them for the reader to work with as he attempts to comprehend the phenomenon of Ernest Hemingway."

The photographic metaphor is apt. This is the life as it would have been recorded by an expert cameraman, who carried along tapes to record Hemingway's conversations, and who had permission to look over his shoulder as he wrote his letters. Here therefore are the "thousand scenes" in which he was involved from boyhood on: the adventures in the First World War, his days as a newspaperman, living in Paris and perfecting his style (starting out in 1922 it took him four months to write six entirely satisfactory sentences), his marriages, the years of success and renown, Spain, his bully-boy exploits in World War II, the decay of his powers, his suicide. But do these pictures, though they enable us to see Hemingway with great clarity, also enable us to comprehend the phenomenon of Ernest Hemingway"

In planning this biography Baker seems to lave made an important theoretical decision The method of the book would be something like that of a Hemingway story. In Death in the Afternoon Hemingway described his own method by comparing it to an iceberg. "The dignity of movement of an iceberg," he said, "is due to only one-eighth of it being above water." In his stories, much of the meaning is beneath the surface, and so the details of the stories continually suggest startling things concealed deeply underneath. In writing a story, he thought, "you could omit anything if you knew what you omitted, and the omitted part would strengthen the story and make people feel something more than they understood." Some similar theory underlies Baker's biography. He is ruthlessly objective. He shows the life admirably. He evidently expects what is thus seen and heard to suggest the experience, the psychological reality - the seven-eighths of Hemingway that lies behind the pictures.

Above all, he does not allow the fiction to comment on the external reality of the life. I do not mean that he ought to have written a "critical biography," repeating here what he has already said in his critical study of Hemingway. But there is a strange lack of congruence between the outer events of the life and what we can discern, through the fiction, as the inward reality. Hemingway boxed with Morley Callaghan, skied in the Alps, went to bullfights, drank at the Dome; but at the same time he was writing In Our Time, projecting a nightmare world of deaths, screams, fear, homosexuality, violence, and despair.

How relevant this is to biography may be glimpsed in the following minor "picture" and the trouble Baker runs into when he comments on it. It is 1932, and Hemingway, in Key West, is revising the galley proofs of Death in the Afternoon. As he works the proofs over he happens to notice at the top of each long sheet a printer's abbreviation of the book's title: "Hemingway's Death." He loses control. Here is Baker's account:

As he knew perfectly well, it was only typesetter's shorthand for the full title. But his irascibility was such that he 'chose to make an issue of it. "DID IT SEEM VERY FUNNY TO SLUG EVERY GALLEY HEMINGWAY'S DEATH," he wired Perkins, "OR WAS THAT WHAT YOU REALLY WANTED?" Next day he wrote that he would like to break the neck of the punk who was responsible. For one who was superstitious to start with, it was a hell of a damn dirty business to stare at those two words a thousand times while reading the proof. In the latest "filthy batch" some nameless nincompoop had even written out the offending words in red and purple ink! If he died in the midst of proofreading, Perkins' goddamned typesetter would be to blame.

Irascibility! In Hemingway's fiction the role of death is absolutely central. Hemingway was, in a real sense, born as a writer when he had to face the fact of his own mortality on the Italian front during World War I. It is fair to say that all his best writing is indirectly about death - about life lived under the aspect of mortality, and about how death can be faced. And so Baker's "irascibility," which is simply left hanging in the "photographic" biography, is drastically inadequate as a description of Hemingway's behavior.

This inadequacy is paradigmatic. All sorts of manic behavior are explained in just such terms. A middle-aged Hemingway, we hear, was "still a boy." This, in my opinion, is the last thing he was. Rather, as Malcolm Cowley once said, he was a haunted writer, akin to Hawthorne and Melville. He was a lot like Picasso's painting of a woman looking into a mirror - one face full of sunlight and health (Hemingway the fighter, lover, hunter, drinker, fisherman, humorist); but the other face, the night face, sick with the awareness of nothingness: traumatized, haunted by death, pain, fear, nada. It is this second "night-face" that doesn't quite get into Baker's biography, and without it much remains inexplicable in his behavior itself - from the special desperate quality of his pursuit of pleasure to his extraordinarily difficult personal relationships. His relationship with Scott Fitzgerald, for example, was incredibly complex. It is all through the fiction of both writers. To each the other was a challenge, but also a threat: each saw, I think it can be shown, the psychic weaknesses of the other. This kind of complexity does not get into Baker's biography; much of the iceberg remains out of sight.

Still, there is so much here that one is glad to know. About Hemingway's wives for example. On Baker's showing, Hemingway was oddly passive in bringing about the last three marriages; after his first marriage, he seems to have had little to do with willing these transactions. And we gather from Baker as well as from Hemingway's own remarks in A Movable Feast that his acquiescence in the destruction of his first marriage - Pauline Pfeiffer's money played an important role - was a disaster he always regretted.

Much of Hemingway's reputed Don Juanism was daydream and idle boast. He did not, for example, have intercourse with the nurse in Milan who provided the model for Catherine Barkley. For all his boasts, Hemingway was rather straight-laced; though in one wild episode while on safari he went native, hunted with a spear, and acquired a young native girl as a mistress. His reputation as a sportsman, on the other hand, was genuinely deserved. He was an expert shot and deep-sea fisherman, a good swimmer and boxer. And though there is something pathological in the way in which he sought out danger in combat, the courage he showed in the front lines during World War II was real enough.

Everywhere you turn in Baker there are interesting details. In 1950, for example, Evelyn Waugh defended Hemingway against charges of brutishness and primitivism, calling him a proponent of "decent feeling" with an "elementary sense of chivalry." This conjunction of Hemingway and Waugh is suggestive. At first no two writers seem more unlike; but when you reflect upon it, affinities appear. Baker also has important things to say about the way pressure from the critics in the 1930's forced him to become political, beginning with To Have andHave Not, a development which went against the grain of his solitary genius, but which provides another example of his passivity, as well as of his consuming desire for critical and financial success.

Baker is also completely convincing about Hemingway's suicide in 1961. Not only had he been physically undermined by his astonishing multiplicity of wounds and in- juries, but his personality had, for at least a decade, been showing signs of disintegration. Paradoxically, Scott Fitzgerald's manifest vulnerability proved psychologically and morally more resilient and enduring than Hemingway's famous toughness.

Mr. Hart is Associate Professor of Englishat Dartmouth and for some years has madErnest Hemingway a particular interest.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

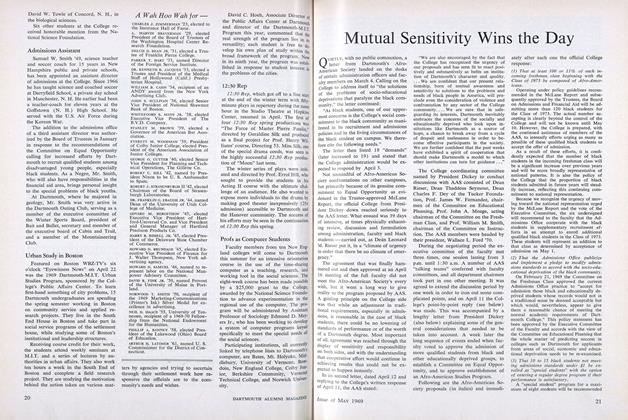

FeatureMutual Sensitivity Wins the Day

May 1969 By JOHN DICKEY -

Feature

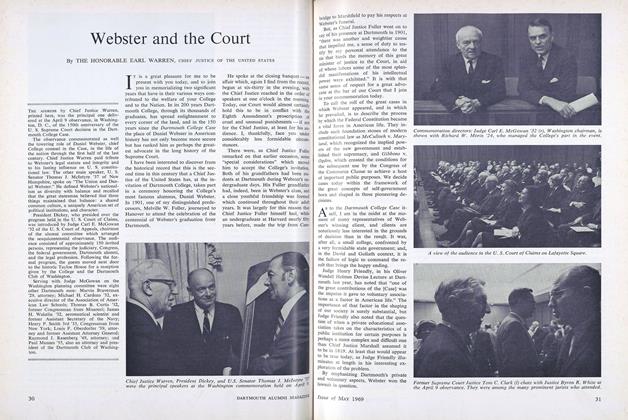

FeatureWebster and the Court

May 1969 By THE HONORABLE EARL WARREN -

Feature

FeatureWarner's 41 Dramatic Years

May 1969 By MARGARET BECK McCALLUM -

Feature

FeatureMay 17 Event to Salute Eleazar's Starting Point

May 1969 -

Article

ArticleThe Undergraduate Chair

May 1969 By CHRIS KERN '69 -

Class Notes

Class Notes1934

May 1969 By STANLEY H. SILVERMAN, WILLIAM S. EMERSON

JEFFREY HART '51

-

Letters to the Editor

Letters to the EditorLetters

SEPTEMBER 1983 -

Letters to the Editor

Letters to the EditorLetters

DECEMBER • 1985 -

Books

BooksGUARDED BY WOMEN.

MAY 1964 By JEFFREY HART '51 -

Books

BooksBOSWELL'S POLITICAL CAREER.

JULY 1965 By JEFFREY HART '51 -

Books

BooksSparing No Expense

June 1975 By JEFFREY HART '51 -

Article

ArticleGrades Ad Parnassum

MARCH 1978 By JEFFREY HART '51

Books

-

Books

BooksAlumni Articles

December 1960 -

Books

BooksSTATE AND FEDERAL CORRUPT PRACTICES LEGISLATION

JANUARY 1929 By Harold R.Bruce -

Books

BooksTHE ACHIEVEMENT OF RICHARD EBERHART.

MAY 1968 By J. D. O'HARA '53 -

Books

BooksNEW JERSEY HISTORICAL PROFILES REVOLUTIONARY TIMES.

April 1974 By JOHN HURD '21 -

Books

BooksAMERICAN SCHOOLS, A CRITICAL STUDY OF OUR SCHOOL SYSTEM,

October 1943 By Louis P. Benezet '99 -

Books

BooksZilpah's Boy

JAN./FEB. 1980 By Richard W. Bailey '61