"I BET there isn't a town in New A England - maybe the country - that has better elms than we have here in Hanover."

The speaker was J. Gordon Cloud, the Norwich man who is coming up on his 50th year of keeping a solicitous eye on the College's trees in general and these stately fountains of greenery in particular. He was speaking with justifiable pride about his custody of these lovely but fragile trees, for Hanover's American elms have been no less susceptible to the devastating Dutch elm disease than have those in Connecticut or Ohio or any number of other states east of the Mississippi.

However, due to the perseverance and solicitude and just plain stubbornness of Gordon Cloud and those working under and over him, a significant number of Hanover's elms still lift their distinctive wine-glass crowns to the skies. While this is heartening, the statistics for the past score or so of years are somewhat grimmer.

Since 1954, when the College began keeping figures on Dutch elm disease (one tree was removed that year) through most of 1976, when 52 were taken down, 797 elms have been lost in Hanover. Of this number 272 were on College property; 269 on town property; and the remainder either on private property or on land of unknown ownership. Richard Plummer '54, superintendent of buildings and grounds, estimates there are perhaps 250-300 elms left on College property.

Further than that, he says that 1976 was "a bad year for Dutch elm disease everywhere."

There is a tiny ray of hope that a chemical solution known as Benlite-P, which is held under patent by the DuPont Corporation, may turn out to be an effective preventative and possibly a cure for the disease. Used as a therapeutic agent in an attempt to save already diseased trees, Benlite is pumped into the vascular system of an elm through a severed root. As a preventative applied to healthy trees, it is pumped into holes drilled in the trunk of the tree. Benlite-P is a recent soluble form of Benlate, also a DuPont product, and is more easily absorbed by elms.

A good part of the impetus for the Benlite treatment, including pressure on DuPont to release the chemical for the treatment, has come from the Elm Research Institute of Harrisville, New Hampshire, which distributed more than 7,500 gallons of the fungicide to arborists, municipalities, universities, and private individuals in 1975. The jury, quite properly, is still out on the efficacy of Benlite, but preliminary figures are hopeful.

The overall prognosis on the American elm and Dutch elm disease has changed a bit from the 1950s and 1960s, when the range of the disease was widening and dire predictions were made that the elm would go the way of the American chestnut. Experts point out that the elm is now seeding heavily in the wild and that over the long haul, the species is safe.

Such a cheery millennial view is cold comfort, however, to communities that have seen whole arcades of elms disappear from their streets, or the wide and gentle shade of them fade from parks and village greens to be replaced by lovely, but lesser, trees - maples, say. That is why so many and so various efforts have been made to fend off the disease, which has only been known in the United States since 1930.

THE disease, which most arborists believe originated in the Orient, acquired its name from the fact that it made its first recorded outbreak in Holland and was first analyzed by Dutch plant pathologists. It is, they determined, caused by a fungus which attacks the water-conducting vessels of the tree. The fungus, ceratocystis ulmi, can exist in living trees as a parasite, but can also exist and reproduce in dead elm wood as a saprophyte, or an organism that lives on decayed organic material.

A European elm-bark beetle, with a flight range of several hundred yards, is the culprit in spreading the disease. These beetles breed beneath the bark of dead or dying trees and there come in contact with the fungus. When they emerge to feed on healthy trees, they carry the fungus with them.

The nature of the disease was first isolated in 1921 by a University of Utrecht researcher. Within a year it had visited Belgium and a good bit of northern France. It leap-frogged the English Channel in 1926, had spread through most of Europe by the late 1920s and by 1930 it was discovered in Ohio, at Cleveland and Cincinnati.

The agent in bringing the disease to the United States was elm burl logs imported from Europe by veneer manufacturing plants. Ironically, it is only this wood from the elm, which is caused by a goiter-like formation on the trees, which has any value at all in the wood-working world.

It wasn't, however, until the mid-1930s that the burl logs were discovered to be harboring both the fungus and the beetles. And, although the importation of them was banned in 1935, the threat to the elm population of North America was already mounted.

ALTHOUGH the word "elm" has been used this far and will continue to be so used, it is really shorthand for a particular species, the American, or white elm, the ulmusamericanus. It has been a particularly loved and protected tree throughout American history. In a tribute to the elm several years ago in a "Profile" entitled "The Great Green Cloud," Berton Roueché, the gifted New Yorker writer, said that the beauty of the tree "owes nothing to flower and little to leaf, and everything to structure. It is an architectural beauty, a splendor of line and form."

Roueche, in classic New Yorker style, was being both precise and restrained. More so, in fact, than an earlier commentator, Oliver Wendell Holmes, from whom he got the title for his profile. For the good doctor, in rather non-Brahmin and un-Holmesian effusiveness, described the effect of a particularly noble elm upon himself as: "I saw a great green cloud swelling in the horizon, so vast, so symmetrical, of such Olympian majesty and imperial supremacy among the lesser forest growths, that my heart stopped short, then jumped at my ribs as a hunter springs at a five-barred gate."

Five-barred gates aside, there is no denying the affection Americans have entertained for elms. As Roueche points out in his article, there have been elms running all through American history - the Washington Elm in Cambridge, Massachusetts, under which the Father of His Country assumed command of the rebel army; Penn's Elm in Philadelphia, under which the good Quaker gained title to the Keystone State; and numerous Liberty Trees (all elms), under which New England Sons of Liberty pledged their opposition to the Stamp Act of 1765.

And there is in Northwood, New Hampshire, as anyone who has driven from Hanover to Durham can testify, what is believed to be the granddaddy of all the elms - the Berry Elm - which, with a circumference of more than 23 feet, is said to be the largest and oldest elm in the United States. Estimates place its age at more than 300 years, so it could well have been standing when the Mayflower reached these shores.

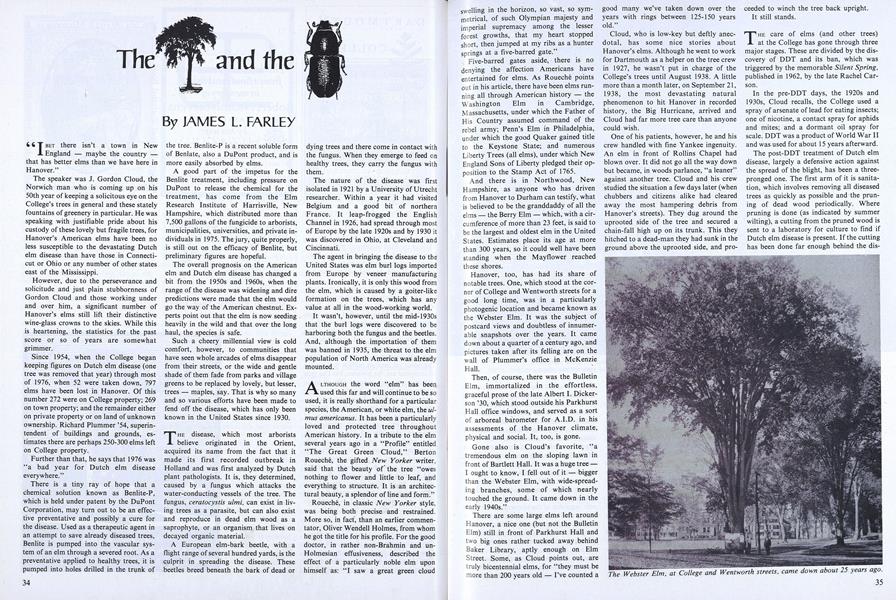

Hanover, too, has had its share of notable trees. One, which stood at the corner of College and Wentworth streets for a good long time, was in a particularly photogenic location and became known as the Webster Elm. It was the subject of postcard views and doubtless of innumerable snapshots over the years. It came down about a quarter of a century ago, and pictures taken after its felling are on the wall of Plummer's office in McKenzie Hall.

Then, of course, there was the Bulletin Elm, immortalized in the effortless, graceful prose of the late Albert I. Dickerson '30, which stood outside his Parkhurst Hall office windows, and served as a sort of arboreal barometer for A.I.D. in his assessments of the Hanover climate, physical and social. It, too, is gone.

Gone also is Cloud's favorite, "a tremendous elm on the sloping lawn in front of Bartlett Hall. It was a huge tree - I ought to know, I fell out of it - bigger than the Webster Elm, with wide-spreading branches, some of which nearly touched the ground. It came down in the early 1940s."

There are some large elms left around Hanover, a nice one (but not the Bulletin Elm) still in front of Parkhurst Hall and two big ones rather tucked away behind Baker Library, aptly enough on Elm Street. Some, as Cloud points out, are truly bicentennial elms, for "they must be more than 200 years old - I've counted a good many we've taken down over the years with rings between 125-150 years old."

Cloud, who is low-key but deftly anecdotal, has some nice stories about Hanover's elms. Although he went to work for Dartmouth as a helper on the tree crew in 1927, he wasn't put in charge of the College's trees until August 1938. A little more than a month later, on September 21, 1938, the most devastating natural phenomenon to hit Hanover in recorded history, the Big Hurricane, arrived and Cloud had far more tree care than anyone could wish.

One of his patients, however, he and his crew handled with fine Yankee ingenuity. An elm in front of Rollins Chapel had blown over. It did not go all the way down but became, in woods parlance, "a leaner" against another tree. Cloud and his crew studied the situation a few days later (when chubbers and citizens alike had cleared away the most hampering debris from Hanover's streets). They dug around the uprooted side of the tree and secured a chain-fall high up on its trunk. This they hitched to a dead-man they had sunk in the ground above the uprooted side, and proceeded

to winch the tree back upright.

It still stands.

THE care of elms (and other trees) at the College has gone through three major stages. These are divided by the discovery of DDT and its ban, which was triggered by the memorable Silent Spring, published in 1962, by the late Rachel Carson.

In the pre-DDT days, the 1920s and 1930s, Cloud recalls, the College used a spray of arsenate of lead for eating insects; one of nicotine, a contact spray for aphids and mites; and a dormant oil spray for scale. DDT was a product of World War II and was used for about 15 years afterward.

The post-DDT treatment of Dutch elm disease, largely a defensive action against the spread of the blight, has been a three-pronged one. The first arm of it is sanitation, which involves removing all diseased trees as quickly as possible and the pruning of dead wood periodically. Where pruning is done (as indicated by summer wilting), a cutting from the pruned wood is sent to a laboratory for culture to find if Dutch elm disease is present. If the cutting has been done far enough behind the diseased portion of the tree and done soon enough, the tree often can be saved.

The second arm of the treatment is deep-root feeding, which is done on a two-year basis in an attempt to keep the trees healthy. The third is a spraying program - a spring spray with methoxychlor (two sprays about a week apart) and a foliar spray around the middle of June.

Of course, there is still the small ray of hope of Benlite. Dartmouth has not been slow to try this route, either. It started an experimental program in 1972 by treating ten elms by trunk injection, and has begun to treat other selected ones by root injection. The data, as indicated earlier, is still inconclusive on this treatment. In any case, it is manifestly impossible, even if the data proves the treatment efficacious, to inject every elm in the township of Hanover.

"I guess you could describe our success," Plummer said in a 1974 memo to vice president Rodney A. Morgan '44, "as a delaying action until a real cure or preventative can be found."

As a corollary to all of this, work has been done on trying to develop Dutch-elmdisease-resistanttrees. One is named the Buisman elm, after an early University of Utrecht researcher. About a half-dozen have been planted on the Dartmouth campus, some by Russell Sage and Richardson dormitories. And some hackberry trees have been planted over the years, but Plummer will only say, "They look something like elms."

The Buismans, disease resistant or not, "will never replace the American elm," in Cloud's opinion, with what he succinctly calls "the umbrella shape."

A look at that shape was given all of us by Adrian Bouchard, the College photographer, who retired last July. As one of his many valedictories (which promise happily to be as numerous as Sarah Bernhardt's) he picked out, for the front cover of the June issue of this magazine, a wonderful, regal shot of his of a line of these majestic trees as they once stood in front of Dartmouth Row by College Street in the 1930s. The archives in Baker Library has a bulging couple of folders of absolute tunnels of elms covering various Hanover streets, but notably Main Street, which can give assiduous researchers yet other glimpses of these shapes as they existed in the 1890s.

Roueché quoted the 18th-century French botanical explorer Andre Michaux as typifying the elm as "the most magnificent vegetable of the temperate zone." Let us hope that Benlite-P will bring it back to flourish in the garden of the Hanover Plain again, and that we will not have to live by photographs, however regal, alone.

The Webster Elm, at College and Wentworth streets, came down about 25 years ago.

Arching elms and maples made north Main Street a bosky place in 1886. Parkhurstand other administration buildings now occupy the block at the right of the picture.

James L. Farley '42, himself an assessor ofthe physical and social climate of Hanover,is a frequent contributor to this magazine.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureJUST LIKE THE REST OF US

November 1976 By A. KELLEY FEAD -

Feature

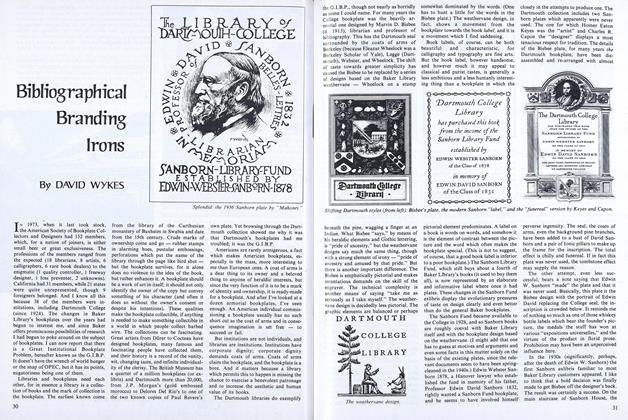

FeatureBibliographical Branding Irons

November 1976 By DAVID WYKES -

Feature

FeatureFive Deadly Threats

November 1976 By John G. Kemeny -

Article

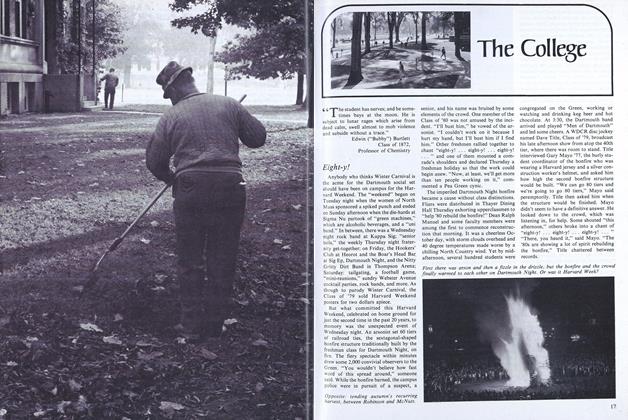

ArticleEight-y!

November 1976 -

Article

ArticleAlan versus Them 'It would be boring otherwise'

November 1976 By PIERRE KIRCH'78 -

Article

ArticleEleazar, Dan and Liz

November 1976 By ELIZABETH CRONIN '77

JAMES L. FARLEY

-

Class Notes

Class Notes1942

October 1948 By JAMES L. FARLEY, JOHN H. HARRIMAN -

Class Notes

Class Notes1942

October 1951 By JAMES L. FARLEY, JOHN H. HARRIMAN -

Class Notes

Class Notes1942

December 1951 By JAMES L. FARLEY, JOHN H. HARRIMAN -

Class Notes

Class Notes1942

May 1948 By JAMES L. FARLEY, JOHN H. HARRIMAN, ADDISON L. WINSHIP II -

Class Notes

Class Notes1942

March 1951 By JAMES L. FARLEY, JOHN H. HARRIMAN, ADDISON L. WINSHIP II -

Class Notes

Class Notes1942

February 1951 By JAMES L. FARLEY, JOHN H. HARXIMAN

Features

-

Feature

FeatureClass Rankings on 1940 Achievement

April 1941 -

Feature

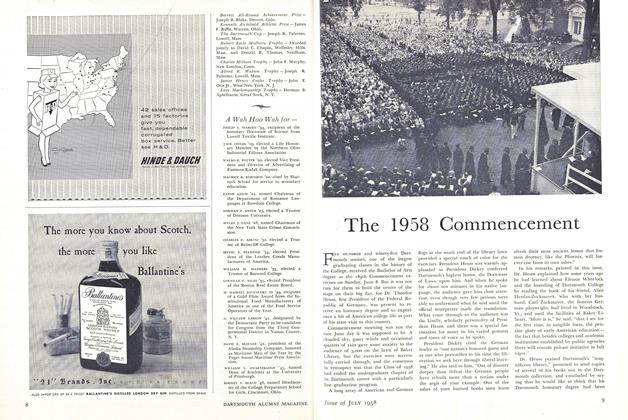

FeatureThe 1958 Commencement

July 1958 By C.E.W. -

Feature

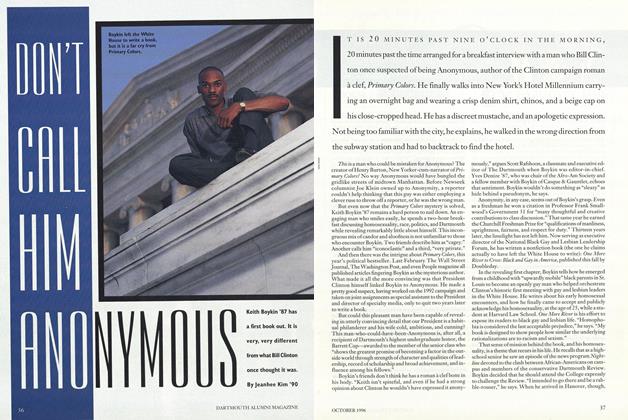

FeatureDON'T CALL HIM ANONYMOUS

OCTOBER 1996 By Jeanhee Kim '9O -

Cover Story

Cover StoryHoney, They're HOME

January 1996 By Mary Cleary Kiely '79 -

Feature

FeatureThe Dinan Decade

OCTOBER, 1908 By Shelby Grantham -

Feature

FeatureThayer School's Centennial

OCTOBER 1971 By WILLIAM P. KIMBALL '28