I have a strong feeling of pride about the significant role that colleges and universities have played in the history of our nation. Particularly during its second century they seem to have been almost a decisive force. They have vastly expanded human knowledge, they proved to be a major force in upward mobility in our society, and they have helped the growth and strengthening of our nation. One would therefore think that in this Bicentennial year higher education in the United States would be basking in its glory. Instead, today, the system of higher education is under, attack from all sides and is fighting for survival.

The most obvious attack is financial, and therefore I shall dwell on it least. The fiscal developments of the 1970s almost seem to have been designed to ruin higher education, particularly private education. The recession has hurt many of our sources of income; rapid inflation has doubled our costs in a few years; the safety of our endowment has been eroded by a decade of lack of growth on the stock market; the cost of our energy has quadrupled; and now a rapidly declining population in the number of 18-year-olds, which will be significantly smaller 15 years from now, is threatening many institutions. But if the only threat were financial, most colleges would survive because they have survived very difficult financial periods in the past.

THERE are much deadlier attacks abroad today. It is becoming quite common for the national media to have periodic critiques on the subject of "Is college worth the money you pay to go there?" These attacks are primarily on private higher education, where the customer pays the bill instead of the taxpayer. And it is true that if you look at the rise of the cost of college, you find some staggering increases. In 1940, tuition, room and board at Dartmouth was $910 a year. It has since increased seven-fold. That fact in isolation is quite scary. But I happen to remember 1940 very well. It was the year I arrived in the United States and settled in New York City. Some of the things I remember very well from that year are that you could buy a hot dog in Times Square for a nickel and you could ride the subway forever for another nickel. Both of those costs have increased not seven-fold but ten-fold. And there is a further difference. During the past 36 years there have been vast improvements in our colleges and universities. We have expanded our facilities, we have responded to the knowledge explosion by a greatly expanded curriculum, we offer much greater quality than we did 36 years ago. Yet the last time I had a hot dog in Times Square, I did not notice it was any better than it was 36 years ago, and I can assure you that the New York subway is not nearly as good as it was in 1940.

The media have great fun hammering at absolute costs, but they fail to make meaningful comparisons - especially the most important comparison, that college over these three decades have incosts creased no faster than average family income in the United States. But it is not just the cost that is being attacked. There is a much subtler argument afoot now. It says, "There was a time when colleges used to be a good investment but now they are not."

For example, in an article on higher education a well-known national news magazine asserted: "In 1965 the lifetime income advantage that the recent college graduate could expect was 11 per cent, by 1974 it had fallen to 7 per cent."

I spent considerable time thinking about that particular quotation, and I confess that it puzzles me. How do they know how much a 1965 graduate is going to earn during his or her lifetime, let alone what a 1974 graduate will earn? Of course, they might have some estimates based on somebody's assumption, they might come up with a very crude and rough estimate - which could be off by 50 per cent or 100 per cent, in which case a swing of four per cent does not seem quite as significant as it does in that kind of dramatic statement. I suspect the prediction is about as reliable as foretelling the weather for a certain day six months from now. I would define one of the key aims of a liberal arts education as the hope that when one of our graduates reads a statement like the one quoted above, he or she will recognize it as nonsense.

But there is a more basic question underlying these spurious statistics. The question is whether financial advantage is the purpose of a college education. The original mission of higher education was training for the ministry, closely followed by training of teachers. I doubt that even in the 18th century those were the most highly paid professions in the colonies. And yet individuals flocked to our colleges and universities from the beginning because colleges and universities opened the doors to the most desirable professions - not necessarily the best paid ones. A trend in our society suggests that in order to have people work at undesirable jobs - that is, jobs that most people would rather not take - we give significant financial rewards for such occupations, e.g., to street cleaners. I think this is a just trend. Perhaps the objective of colleges in the long run should be that our graduates should make significantly less money than those who did not go to college! In any case, an earning differential is a very poor measure of the value of college.

I find with some horror that the language of investments is being applied to higher education to compare costs and financial rewards; any day now I expect to see a copy of the Wall Street Journal with a listing of the price/earnings ratios of colleges. The greatest rewards of college have always been intangible. The arousing of curiosity, the satisfaction of a thirst for knowledge, and helping individuals to become better human beings are achievements that cannot be measured in monetary terms.

THE third attack says that there are too many college graduates and we ought to stop turning out more. The same article quoted earlier contained this fascinating claim: "27 per cent of the naion's work force is over-educated." Again, I puzzled about that particular quotation and I asked myself: "Who are these poor 27 per cent who suffer from this terrible disease of over-education?" And all of a sudden it hit me - I am one of them. A Ph.D. in mathematics is hardly a requirement for college presidents, so quite clearly I am in the category of the over-educated.

One can speculate about lots of fascinating examples from the history of mankind. Without doubt Socrates was over-educated. His life could have been quite different - he might have retired as a prosperous businessman if he had not been over-educated or overly interested in intellectual matters, and, of course, the whole history of Western Civilization would have been significantly different. The question we must ask ourselves is why is it that the word "over-educated" is used in a derogatory sense? It presumably means that you know more than you absolutely need to know for your present occupation. Clearly, if you are under-educated, i.e., not qualified for your job, I understand why that is a derogatory term. But why is it somehow a terrible thing if you know more than the absolute minimum you need to know to earn a living? Think about what has happened to our civilization that highly respectable publications can get away with turning a word like "over-educated" into a derogatory term.

THE next attack is that we are not preparing students for today's world. This is one assertion I hope is correct. We shouldn't be preparing young men and women for today's world but for a highly uncertain future. Jobs and requirements for jobs, professions and what is expected of those who hold those professions, change rapidly. If we prepare students precisely for what their profession needs at the moment they enter it, they will be totally unprepared a quarter of a century later. It may very well be that trade schools have an effective short-range objective and are worthwhile, but a liberal education tries to do more than that.

I give you one example from my own life: I never had a course on computers. There is a very simple reason for that - there were no computers when I was in college. Yet when computers came I was able to make a contribution to their development, not because of any one particular thing I had learned but because of the breadth of a liberal arts education I was fortunate enough to acquire, because of learning to think in a certain way, and having been prepared to react to totally unexpected challenges. In a rapidly changing world the need for such a broad liberal education has never been greater. And amidst so many examples of pragmatic amoral behavior amongst the leaders of government and industry, the questioning of fundamental values has never been more important.

I saved for last the fifth attack because it bothers me most. It is a new attack on academic freedom. In our history the right to question has very often been challenged, and the threat is again on the rise. I was quite horrified to learn that some alumni of my own alma mater organized to urge industry not to support their college. They have urged companies to send representatives into the classrooms at that institution to see what is being taught there and urged them not to give financial support unless they like what each professor teaches. I am deeply sorry that alumni of such a great institution learned so very little during their undergraduate years. In this Bicentennial year we must re-assert that censorship of higher education either by government or by those who control wealth is the gravest possible threat to our nation.

Higher education faces great challenges in the nation's third century. Our system of higher education is probably overextended and may have to contract. It is under attack by a pragmatic society that measures value in terms of dollars. It has been forced to re-argue the importance of free expression. It will have to fight - if not for survival - at least for the right to maintain the highest quality. I don't know how successful we will be in responding to these challenges, but I am certain that the outcome will have a decisive influence on the third century of our nation.

This article is adapted from a portion ofPresident Kemeny's Convocation addressin September.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureJUST LIKE THE REST OF US

November 1976 By A. KELLEY FEAD -

Feature

FeatureBibliographical Branding Irons

November 1976 By DAVID WYKES -

Feature

FeatureThe and the

November 1976 By JAMES L. FARLEY -

Article

ArticleEight-y!

November 1976 -

Article

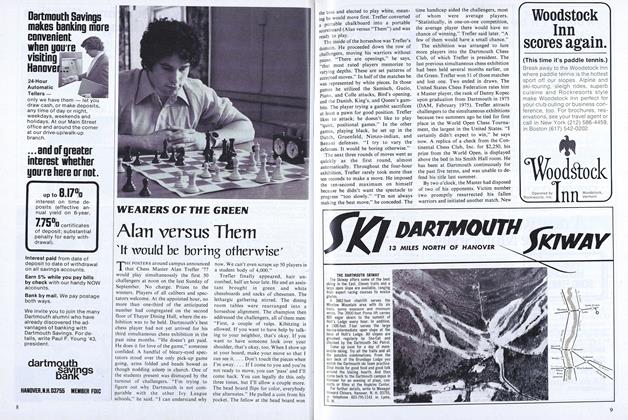

ArticleAlan versus Them 'It would be boring otherwise'

November 1976 By PIERRE KIRCH'78 -

Article

ArticleEleazar, Dan and Liz

November 1976 By ELIZABETH CRONIN '77

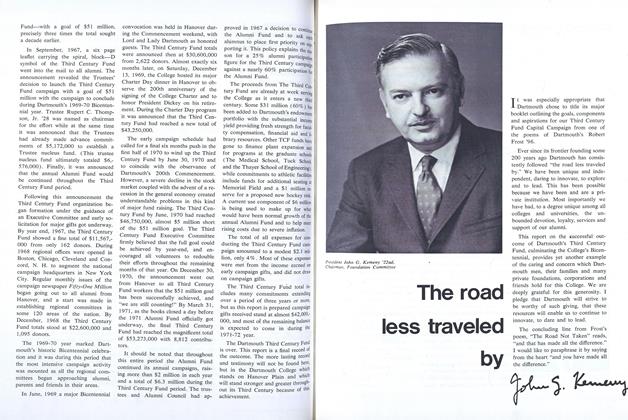

John G. Kemeny

-

Feature

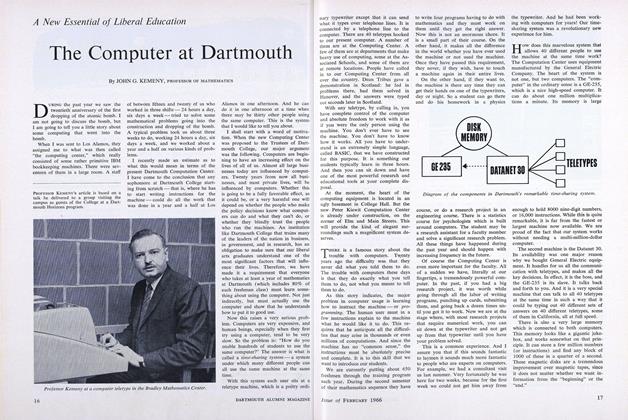

FeatureThe Computer at Dartmouth

FEBRUARY 1966 By John G. Kemeny -

Article

ArticleThe road less traveled

DECEMBER 1971 By John G. Kemeny -

Feature

FeatureThe Bakke Case

OCT. 1977 By John G. Kemeny -

Feature

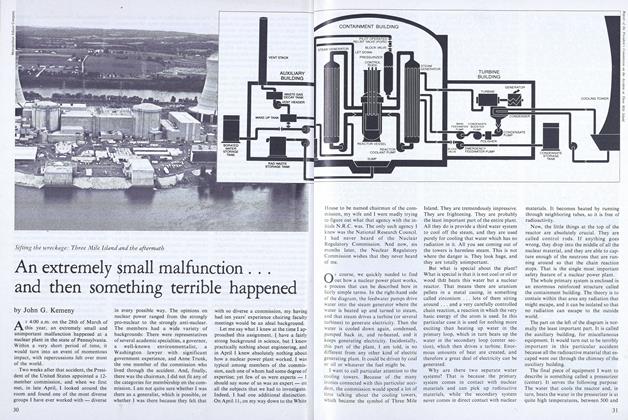

FeatureAn extremely small malfunction ... and then something terrible happened

December 1979 By John G. Kemeny -

Feature

FeatureWHEN THE YOUNG TURKS CAME

December 1990 By John G. Kemeny -

Article

ArticleA Compressed Life

February 1993 By John G. Kemeny

Features

-

Feature

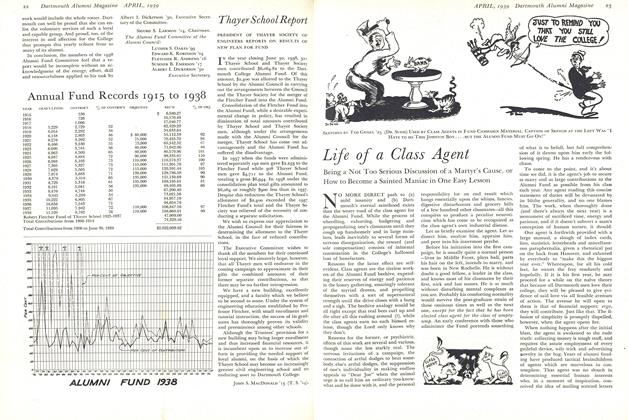

FeatureAnnual Fund Records 1915 to 1938

April 1939 -

Feature

Feature"The Era of the Shrug"

November 1960 -

Feature

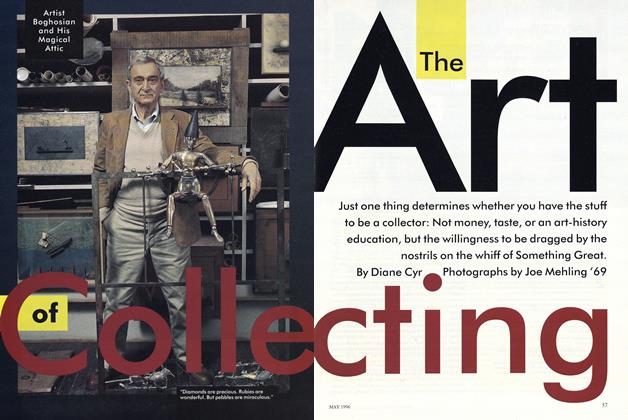

FeatureThe Art of Collecting

MAY 1996 By Diane Cyr -

Feature

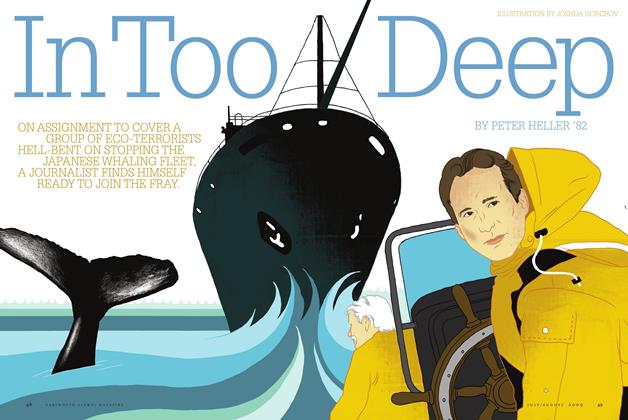

FeatureIn Too Deep

July/Aug 2009 By PETER HELLER ’82 -

Feature

FeatureThe Wooden Shoe: A Commune

May 1979 By Shelby Grantham -

Cover Story

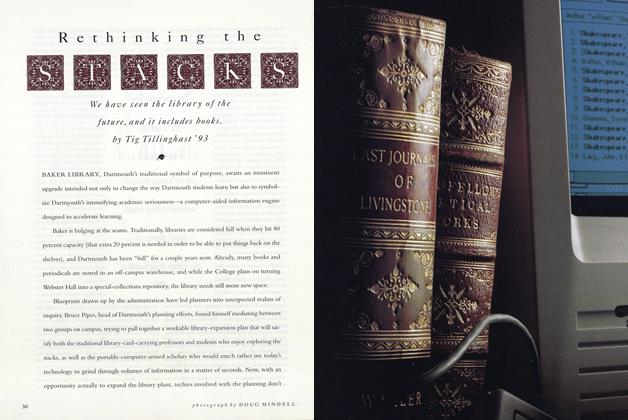

Cover StoryRethinking The Stacks

December 1992 By Tig Tillinghast '93