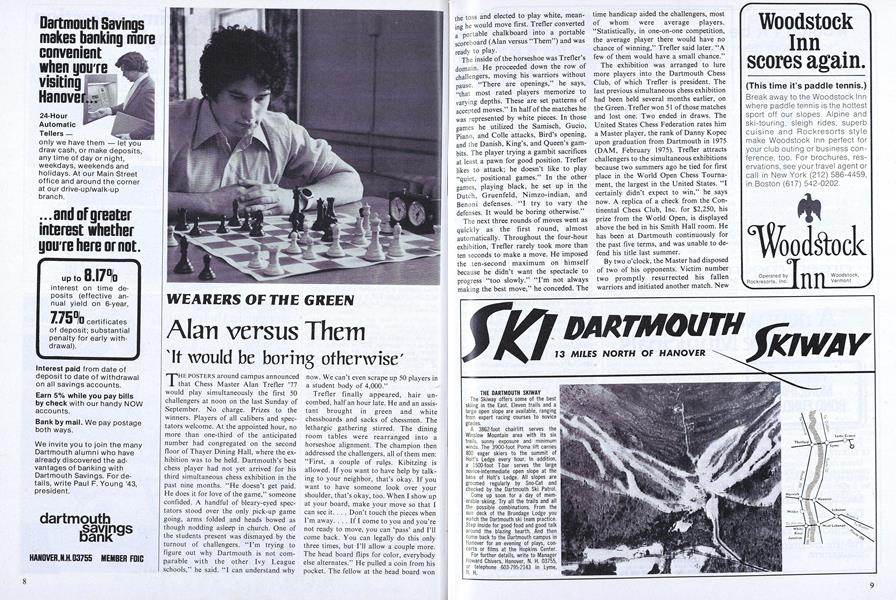

THE POSTERS around campus announced that Chess Master Alan Trefler '77 would play simultaneously the first 50 challengers at noon on the last Sunday of September. No charge. Prizes to the winners. Players of all calibers and spectators welcome. At the appointed hour, no more than one-third of the anticipated number had congregated on the second floor of Thayer Dining Hall, where the exhibition was to be held. Dartmouth's best chess player had not yet arrived for his third simultaneous chess exhibition in the past nine months. "He doesn't get paid. He does it for love of the game," someone confided. A handful of bleary-eyed spectators stood over the only pick-up game going, arms folded and heads bowed as though nodding asleep in church. One of the students present was dismayed by the turnout of challengers. "I'm trying to figure out why Dartmouth is not comparable with the other Ivy League schools," he said. "I can understand why now. We can't even scrape up 50 players in a student body of 4,000."

Trefler finally appeared, hair uncombed, half an hour late. He and an assistant brought in green and white chessboards and sacks of chessmen. The lethargic gathering stirred. The dining room tables were rearranged into a horseshoe alignment. The champion then addressed the challengers, all of them men: "First, a couple of rules. Kibitzing is allowed. If you want to have help by talking to your neighbor, that's okay. If you want to have someone look over your shoulder, that's okay, too. When I show up at your board, make your move so that I can see it.... Don't touch the pieces when I'm away.... If I come to you and you're not ready to move, you can 'pass' and I'll come back. You can legally do this only three times, but I'll allow a couple more. The head board flips for color, everybody else alternates." He pulled a coin from his pocket. The fellow at the head board won the toss and elected to play white, meaning he would move first. Trefler converted a portable chalkboard into a portable scoreboard (Alan versus "Them") and was ready to play.

The inside of the horseshoe was Trefler's domain. He proceeded down the row of challengers, moving his warriors without pause. "There are openings," he says, "that most rated players memorize to varying depths. These are set patterns of accepted moves." In half of the matches he was represented by white pieces. In those games he utilized the Samisch, Gucio, Piano, and Colle attacks, Bird's opening, and the Danish, King's, and Queen's gambits. The player trying a gambit sacrifices at least a pawn for good position. Trefler likes to attack; he doesn't like to play "quiet, positional games." In the other games, playing black, he set up in the Dutch, Gruenfeld, Nimzo-indian, and Benoni defenses. "I try to vary the defenses. It would be boring otherwise."

The next three rounds of moves went as quickly as the first round, almost automatically. Throughout the four-hour exhibition, Trefler rarely took more than ten seconds to make a move. He imposed the ten-second maximum on himself because he didn't want the spectacle to progress "too slowly." "I'm not always making the best move," he conceded. The time handicap aided the challengers, most of whom were average players. "Statistically, in one-on-one competition, the average player there would have no chance of winning," Trefler said later. "A few of them would have a small chance."

The exhibition was arranged to lure more players into the Dartmouth Chess Club, of which Trefler is president. The last previous simultaneous chess exhibition had been held several months earlier, on the Green. Trefler won 51 of those matches and lost one. Two ended in draws. The United States Chess Federation rates him a Master player, the rank of Danny Kopec upon graduation from Dartmouth in 1975 (DAM, February 1975). Trefler attracts challengers to the simultaneous exhibitions because two summers ago he tied for first place in the World Open Chess Tournament, the largest in the United States. "I certainly didn't expect to win," he says now. A replica of a check from the Continental Chess Club, Inc. for $2,250, his prize from the World Open, is displayed above the bed in his Smith Hall room. He has been at Dartmouth continuously for the past five terms, and was unable to defend his title last summer.

By two o'clock, the Master had disposed of two of his opponents. Victim number two promptly resurrected his fallen warriors and initiated another match. New players walked in and started up games. One player meticulously recorded his moves on a sheet of paper. "We have a really bizarre game ... nothing's developed," a challenger said. "I think I got him now," said another. How's that? "I'm not disappointed with my position, let's put it that way." When his next turn came, he traded bishops with Trefler. The match later ended in a draw.

The tireless Trefler continued on the inside of the horseshoe without a break. Last summer, he played continuously on the Green for six hours. "Any good challenge wears you out. You feel good when it's over, to be able to sit down and relax," he says. When Trefler plays in tournaments, he is not a sit-down player; while his opponent cogitates, he moves around and watches other games. In the exhibition, he bantered with his challengers but played seriously. "If I didn't concentrate, I could never pull it off.... All these people are getting more than 20 times the amount of time I'm getting. To make the moves, I've got to be intense." How does he keep the different games straight in his mind? "Not all of them have to be remembered at one time. Sometimes when a game is different or interesting or I'm in a lot of trouble, I remember what's key."

Trefler doesn't play chess every day. But he does play out moves in his head every day. He reads chess games in books like Selected Chess Masterpieces and 100Soviet Chess Miniatures for enjoyment and "to keep in practice." "It is a study.

You have to work at it," he says. He subscribes to Chess Life and Review, a publication that presently lists him as the ninth ranking United States player under age 22. He also reviews compilations of the Grand Master matches to "see what the competition is doing."

At four o'clock, the chalkboard recorded 18 victories for Alan and two for "Them." "I've had a lot of bad games today," Trefler said. Actually, he had won more than 18 matches, but he had stopped keeping score to save time. The dining association would need the room at 4:30. The remaining contestants numbered four and Trefler looked more relaxed.

He won the last four, games, and the final score was 28 wins for Trefler with two losses and two draws. One of the losses resulted from a self-confessed "gross blunder" at the game's outset that caused the forfeiture of his queen. The other loss came when the challenger "made some good moves" and outplayed Trefler. The two vanquishers were both rated players. There are 60,000 rated players in the United States. As for prizes, one of the winners said he would settle for having the $3 Chess Club fee paid for him.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureJUST LIKE THE REST OF US

November 1976 By A. KELLEY FEAD -

Feature

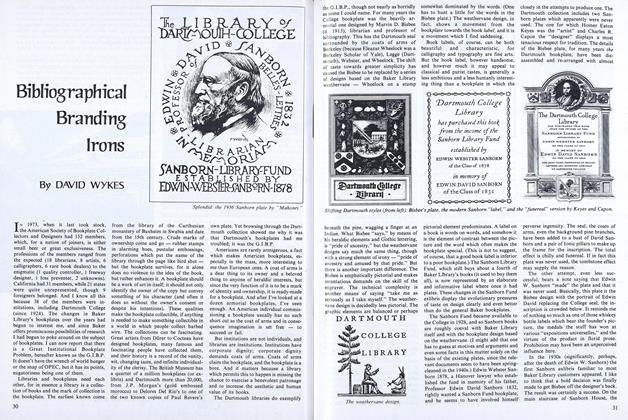

FeatureBibliographical Branding Irons

November 1976 By DAVID WYKES -

Feature

FeatureThe and the

November 1976 By JAMES L. FARLEY -

Feature

FeatureFive Deadly Threats

November 1976 By John G. Kemeny -

Article

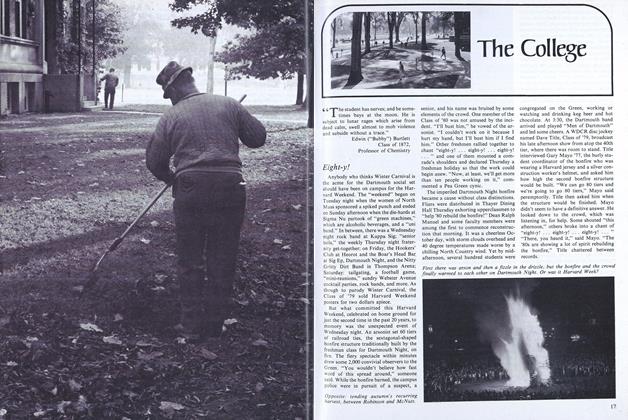

ArticleEight-y!

November 1976 -

Article

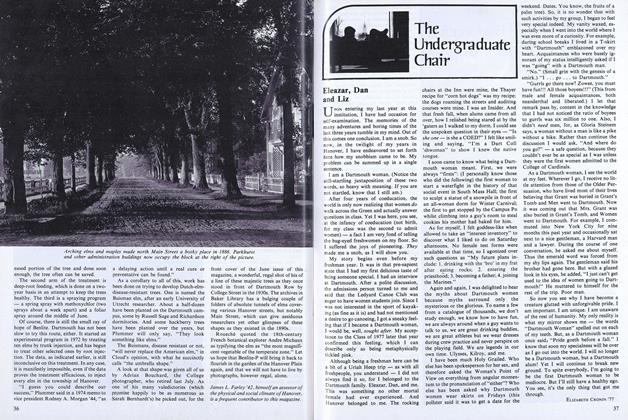

ArticleEleazar, Dan and Liz

November 1976 By ELIZABETH CRONIN '77