From: Lord Dartmouth To: My Namesake Subject: The Rebellion

IN MY TIME I was called "good Lord Dartmouth." Not a whisper of scandal sullied the good name. I had a loving wife and nine obedient children, tended my estates as befitted a peer, and was devout. (One jackanape, making sport of my piety, did call me a "psalm-singer," and, true, my great-grandfather was imprisoned in the Tower, but these were minor quibbles.) I took sincere interest in the Indian and when my king - your king, too - provided £200 to start a school in New Hampshire, I gave £50. I allowed myself no more than mild pique when your Reverend Doctor Wheelock, quite without permission, appropriated my name for his college. My favorite subject at Oxford was mathematics, an art which I understand still earns high favor among you. An exemplary life, I would say.

Yet we were enemies, you and I. In politics I was loyal to my friends and a Whig, and therein lay my troubles. In 1765, at the age of 34, I entered the Rockingham ministry as First Lord of Trade. For helping repeal the hated Stamp Act the people of Massachusetts thanked me for my "noble and generous patronage" and John Randolph of Virginia sent me an eagle. On that happy note I left politics to care for my family and my properties in St, James's Square, in Blackheath, Sandwell Park near Birmingham, and Woodsome Manor in Yorkshire. A lord of the realm has his obligations.

But after my stepbrother, Lord North, led his ministry' into power in 1770, he asked me to serve as Secretary of State for the Colonies. Could I refuse? With a staff of two undersecretaries, one first clerk, two senior clerks, two ordinary clerks, one chamber keeper and his deputy, and a "necessary woman," I thought I could get along nicely.

The first glimmer of difficulty came when that Pennsylvania electrician and his friends encouraged me to open up the Western lands and establish a new colony of Vandalia, comprising what you call, with notable lack of poetry, West Virginia. Then in June of '73 a band of Rhode Island smugglers burned our patrol schooner Gaspée, claiming the captain was a "pirate." You Americans always had a knack for twisting the truth. The Gaspée incident was galling to us and a source of glee to your radicals. Matters were not made any easier by the activities of Dr. Franklin, who - how to put it delicately? - was borrowing letters from the governor of Massachusetts.

You will recall that as a means of raising revenue and coming to the aid of the East India Company, we had levied a threepence-per-pound tax on tea. Barely a year after I took office, in December of '74, your "Indians" protested this mild duty by dumping 340 chests of tea into Boston harbor. Oh yes, one of the tea ships was the Dartmouth. A most unwarrantable insult, as I said at the time.

This was becoming serious, with one challenge to Parliamentary supremacy after another. My king let it be known that firm measures were in order, while I favored mild rebuke and conciliation. Some of my fellow ministers accused me of being soft on America.

In the wake of that little Tea Party came what your Boston hotheads called the Intolerable Acts. I confess to misjudging the temper of the times. "I am willing to suppose," I said, "that the people will quietly submit to the correction of their illconduct...." That wretched Franklin, who once called me "truly a good man," now claimed I was "easily prevailed with to join the worst."

This was base insult. At that very moment my private physician was deputed to carry forth secret negotiations with Franklin toward reconciling the Mother Country with her fractious children. I am afraid that we mistrusted you and that you mistrusted us. I desperately hoped for peace and I worked frightfully hard to bring it about.

April of '75. Lexington and Concord. Shots heard 'round the world, as your man Emerson so quaintly put it. Truth be known, General Gage was not all that I hoped for in a commander. He took orders from me, but wanted instructions for this and instructions for that. He took everything so literally. I suggested it might be a good idea to capture the Massachusetts ringleaders and whatever gunpowder could be found, and look what he did. Some even said the war was my fault.

The king, bless him, stood by me, referring to the unhappy events outside Boston merely as "bad news." I began to suspect the worst, but put up a brave front, telling one of my undersecretaries, "... though both sides will have a great way to go before they will be within the sound of each other's voice, it is not impossible that they may come near enough to shake hands at last." Rather nicely put, don't you think?

However, as I wrote Governor Wentworth of New Hampshire, "a spirit of rebellion has gone forth." My job for the next few months was decidedly unpleasant. To my regret, I agreed to the enlistment of Indians as combatants. While I was trying to run a war, the Governor of Virginia was petulantly complaining that his furniture had been lost at sea. That sort of thing. Finally, I gave it up in November of '75, exchanging the post of Secretary of State for the less demanding Lord of Privy Seal. (I had been offered Groom of the Stole, but wouldn't accept.) My last official act in the American Department was to authorize the evacuation of Boston.

So now you Americans, you men of Dartmouth, celebrate your Revolution. You won and we lost. If I had had my way, we still would be brothers, but perhaps it is not too late "to shake hands at last."

There is one thing I ought to tell you. While old Wheelock, who thought he was so shrewd, was using my name without my permission, I was wondering what to do with this grant of land I had acquired somewhat to the south of you. What land? Oh, just 100,000 acres in east Florida, encompassing a place they now call Miami. Ever heard of it?

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureGod and Man at Dartmouth

March 1976 By DAN NELSON -

Feature

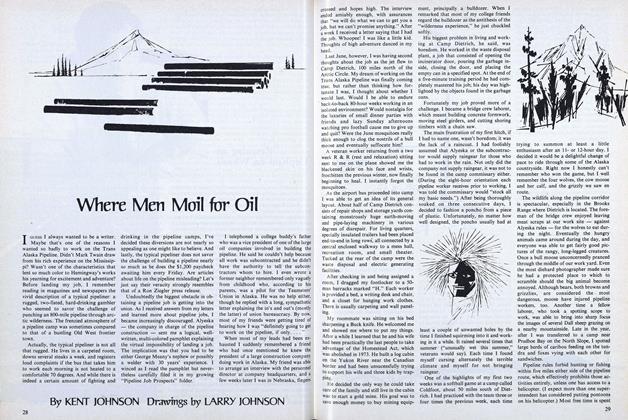

FeatureWhere Men Moil for Oil

March 1976 By KENT JOHNSON -

Feature

FeatureOPTIONS & ALTERNATIVES

March 1976 By D.N. -

Article

ArticlePeople & Places

March 1976 By JACK DEGANGE -

Class Notes

Class Notes1974

March 1976 By STEPHEN D. SEVERSON, JACK E. THOMAS JR. -

Class Notes

Class Notes1919

March 1976 By WINDSOR C. BATCHELDER, CHESTER W. DeMOND

Features

-

Feature

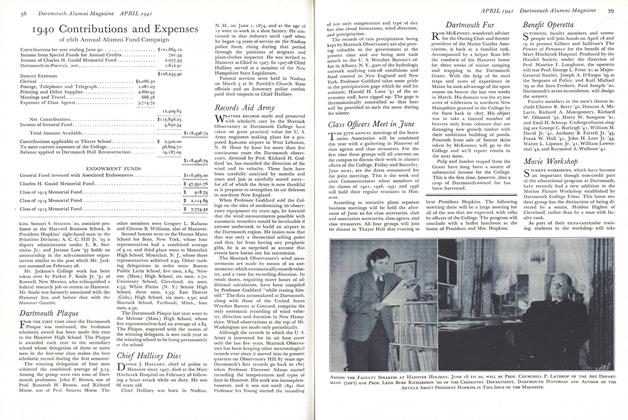

Feature1940 Contributions and Expenses of 26th Annual Alumni Fund Campaign

April 1941 -

Feature

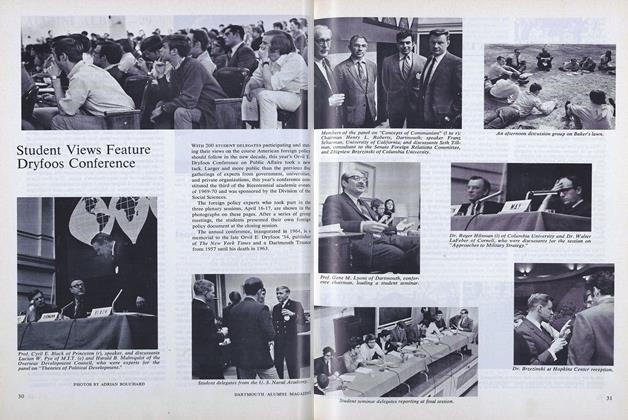

FeatureStudent Views Feature Dryfoos Conference

MAY 1970 -

Feature

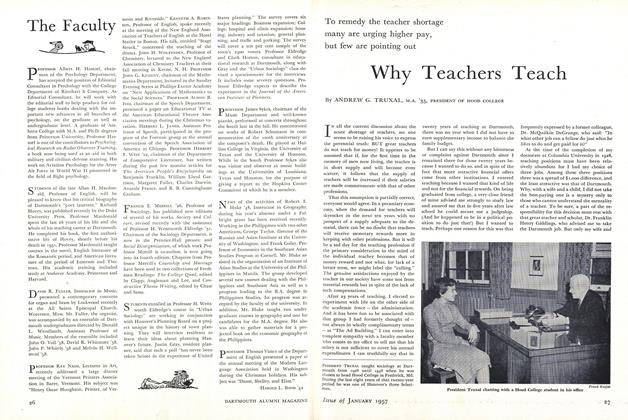

FeatureWhy Teachers Teach

January 1957 By ANDREW G. TRUXAL -

Features

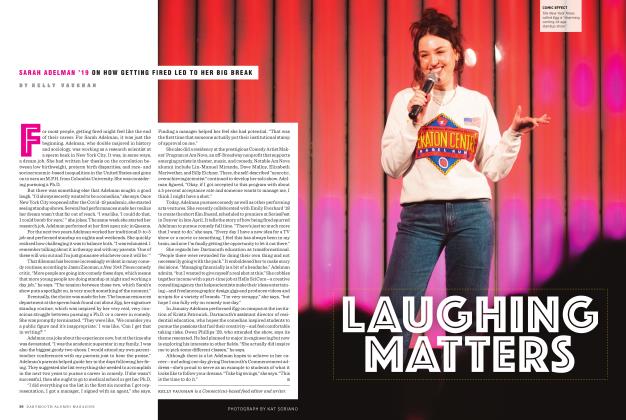

FeaturesLaughing Matters

MAY | JUNE 2025 By KELLY VAUGHAN -

Feature

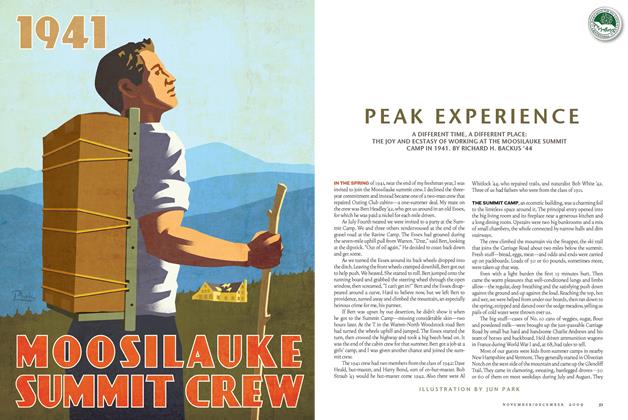

FeaturePeak Experience

Nov/Dec 2009 By RICHARD H. BACKUS ’44 -

Feature

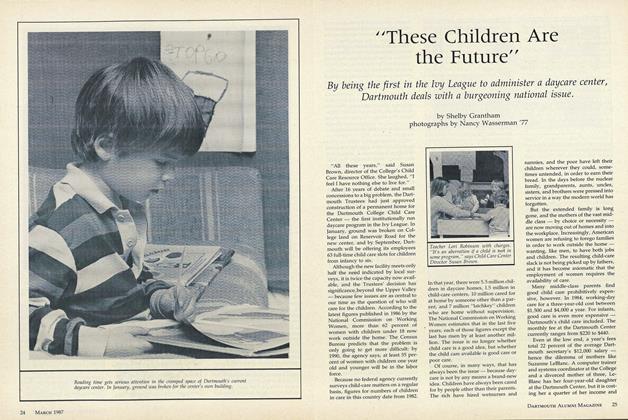

Feature"These Children Are the Future"

MARCH • 1987 By Shelby Grantham