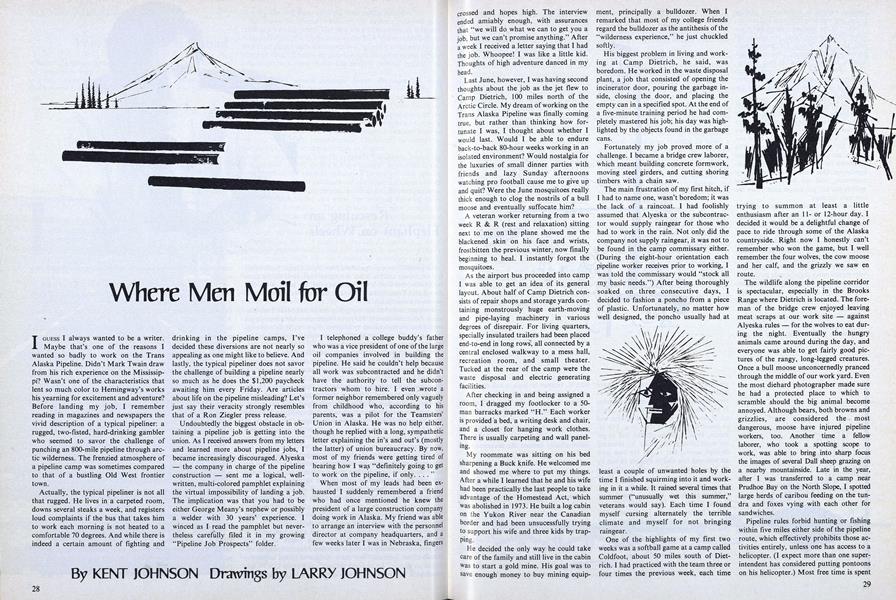

I GUESS I always wanted to be a writer. Maybe that's one of the reasons I wanted so badly to work on the Trans Alaska Pipeline. Didn't Mark Twain draw from his rich experience on the Mississippi? Wasn't one of the characteristics that lent so much color to Hemingway's works his yearning for excitement and adventure? Before landing my job, I remember reading in magazines and newspapers the vivid description of a typical pipeliner: a rugged, two-fisted, hard-drinking gambler who seemed to savor the challenge of punching an 800-mile pipeline through arctic wilderness. The frenzied atmosphere of a pipeline camp was sometimes compared to that of a bustling Old West frontier town.

Actually, the typical pipeliner is not all that rugged. He lives in a carpeted room, downs several steaks a week, and registers loud complaints if the bus that takes him to work each morning is not heated to a comfortable 70 degrees. And while there is indeed a certain amount of fighting and drinking in the pipeline camps, I've decided these diversions are not nearly so appealing as one might like to believe. And lastly, the typical pipeliner does not savor the challenge of building a pipeline nearly so much as he does the $1,200 paycheck awaiting him every Friday. Are articles about life on the pipeline misleading? Let's just say their veracity strongly resembles that of a Ron Ziegler press release.

Undoubtedly the biggest obstacle in obtaining a pipeline job is getting into the union. As I received answers from my letters and learned more about pipeline jobs, I became increasingly discouraged. Alyeska - the company in charge of the pipeline construction - sent me a logical, wellwritten, multi-colored pamphlet explaining the virtual impossibility of landing a job. The implication was that you had to be either George Meany's nephew or possibly a welder with 30 years' experience. I winced as I read the pamphlet but nevertheless carefully filed it in my growing "Pipeline Job Prospects" folder.

I telephoned a college buddy's father who was a vice president of one of the large oil companies involved in building the pipeline. He said he couldn't help because all work was subcontracted and he didn't have the authority to tell the subcontractors whom to hire. I even wrote a former neighbor remembered only vaguely from childhood who, according to his parents, was a pilot for the Teamsters' Union in Alaska. He was no help either, though he replied with a long, sympathetic letter explaining the in's and out's (mostly the latter) of union bureaucracy. By now, most of my friends were getting tired of hearing how I was "definitely going to get to work on the pipeline, if only...."

When most of my leads had been exhausted I suddenly remembered a friend who had once mentioned he knew the president of a large construction company doing work in Alaska. My friend was able to arrange an interview with the personnel director at company headquarters, and a few weeks later I was in Nebraska, fingers crossed and hopes high. The interview ended amiably enough, with assurances that "we will do what we can to get you a job, but we can't promise anything." After a week I received a letter saying that I had the job. Whoopee! I was like a little kid. Thoughts of high adventure danced in my head.

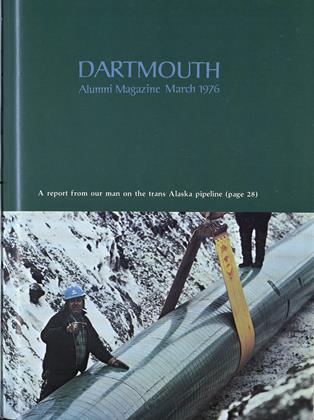

Last June, however, I was having second thoughts about the job as the jet flew to Camp Dietrich, 100 miles north of the Arctic Circle. My dream of working on the Trans Alaska Pipeline was finally coming true, but rather than thinking how fortunate I was, I thought about whether I would last. Would I be able to endure back-to-back 80-hour weeks working in an isolated environment? Would nostalgia for the luxuries of small dinner parties with friends and lazy Sunday afternoons watching pro football cause me to give up and quit? Were the June mosquitoes really thick enough to clog the nostrils of a bull moose and eventually suffocate him?

A veteran worker returning from a two week R & R (rest and relaxation) sitting next to me on the plane showed me the blackened skin on his face and wrists, frostbitten the previous winter, now finally beginning to heal. I instantly forgot the mosquitoes.

As the airport bus proceeded into camp I was able to get an idea of its general layout. About half of Camp Dietrich consists of repair shops and storage yards containing monstrously huge earth-moving and pipe-laying machinery in various degrees of disrepair. For living quarters, specially insulated trailers had been placed end-to-end in long rows", all connected by a central enclosed walkway to a mess hall, recreation room, and small theater. Tucked at the rear of the camp were the waste disposal and electric generating facilities.

After checking in and being assigned a room, I dragged my footlocker to a 50-man barracks marked "H." Each worker is provided a bed, a writing desk and chair, and a closet for hanging work clothes. There is usually carpeting and wall paneling.

My roommate was sitting on his bed sharpening a Buck knife. He welcomed me and showed me where to put my things. After a while I learned that he and his wife had been practically the last people to take advantage of the Homestead Act, which was abolished in 1973. He built a log cabin on the Yukon River near the Canadian border and had been unsucessfully trying to support his wife and three kids by trapping.

He decided the only way he could take care of the family and still live in the cabin was to start a gold mine. His goal was to save enough money to buy mining equipment, principally a bulldozer. When I remarked that most of my college friends regard the bulldozer as the antithesis of the "wilderness experience," he just chuckled softly.

His biggest problem in living and working at Camp Dietrich, he said, was boredom. He worked in the waste disposal plant, a job that consisted of opening the incinerator door, pouring the garbage inside, closing the door, and placing the empty can in a specified spot. At the end of a five-minute training period he had completely mastered his job; his day was highlighted by the objects found in the garbage cans.

Fortunately my job proved more of a challenge. I became a bridge crew laborer, which meant building concrete formwork, moving steel girders, and cutting shoring timbers with a chain saw.

The main frustration of my first hitch, if I had to name one, wasn't boredom; it was the lack of a raincoat. I had foolishly assumed that Alyeska or the subcontractor would supply raingear for those who had to work in the rain. Not only did the company not supply raingear, it was not to be found in the camp commissary either. (During the eight-hour orientation each pipeline worker receives prior to working, I was told the commissary would "stock all my basic needs.") After being thoroughly soaked on three consecutive days, I decided to fashion a poncho from a piece of plastic. Unfortunately, no matter how well designed, the poncho usually had at least a couple of unwanted holes by the time I finished squirming into it and working in it a while. It rained several times that summer ("unusually wet this summer," veterans would say). Each time I found myself cursing alternately the terrible climate and myself for not bringing raingear.

One of the highlights of my first two weeks was a softball game at a camp called Coldfoot, about 50 miles south of Dietrich. I had practiced with the team three or four times the previous week, each time trying to summon at least a little enthusiasm after an 11- or 12-hour day. I decided it would be a delightful change of pace to ride through some of the Alaska countryside. Right now I honestly can't remember who won the game, but I well remember the four wolves, the cow moose and her calf, and the grizzly we saw en route.

The wildlife along the pipeline corridor is spectacular, especially in the Brooks Range where Dietrich is located. The foreman of the bridge crew enjoyed leaving meat scraps at our work site - against Alyeska rules - for the wolves to eat during the night. Eventually the hungry animals came around during the day, and everyone was able to get fairly good pictures of the rangy, long-legged creatures. Once a bull moose unconcernedly pranced through the middle of our work yard. Even the most diehard photographer made sure he had a protected place to which to scramble should the big animal become annoyed. Although bears, both browns and grizzlies, are considered the most dangerous, moose have injured pipeline workers, too. Another time a fellow laborer, who took a spotting scope to work, was able to bring into sharp focus the images of several Dall sheep grazing on a nearby mountainside. Late in the year, after I was transferred to a camp near Prudhoe Bay on the North Slope, I spotted large herds of caribou feeding on the tundra and foxes vying with each other for sandwiches.

Pipeline rules forbid hunting or fishing within five miles either side of the pipeline route, which effectively prohibits those activities entirely, unless one has access to a helicopter. (I expect more than one superintendent has considered putting pontoons on his helicopter.) Most free time is spent reading, talking or complaining, playing poker, and watching television and movies.

Many of the pipeline welders hail from either Oklahoma or Texas. It's easy to tell who they are. Watch for leather belts carved with their names, silver-dollar belt buckles, and big "chaws" in their mouths. They like to get together over cheap whiskey and reminisce about the time they "punched out a line from Kilgore to the East Texas line in 41 days."

Of all the pipeline workers, the welders probably do the most complaining. Shortly before I started on the pipeline, the welders had closed one of the camps for four hours because Alyeska had refused to hand out steaks for their lunchtime barbecues. The welders are generally a prideful, competent lot known for not backing down from confrontations. One welder, who later was my roommate, told me he and his fellow welders like to "tell 'em jez zackly how the cow eats cabbage."

Working on the pipeline is most difficult for those who have wives and families, or girlfriends. One mechanic at Dietrich who had been "pipelining" for six months without an R & R received his divorce papers in the mail one day. He told us that was the first time he had known something was wrong with his marriage. I consider myself lucky that the only girlfriend I have is someone from Cadillac, Michigan, whom I met once on a train and who thoughtfully sends me a Christmas card each year.

One of my best friends on the pipeline was a 31-year-old Eskimo named Frank. Because the pipeline route does not pass through many villages, there seems to have been very little effect on the lifestyle of most Eskimos. The main effect, it seems to me, has been to enable them to earn a lot of money in a short period of time and to spend it to improve their lives. For instance, Frank told me that he had to get his water during the winter by breaking through several feet of ice. He lives with his wife and two kids in a house 16 feet by 20. Next summer he hopes to install indoor plumbing or even build an entirely new house with his pipeline earnings.

Many pipeliners, however, spend their money frivolously. One friend of mine arrived home in a Lear Jet. Somehow he was able to locate an airline that would charter it for him for $600 or $700 an hour. On top of that, he arranged for a chaffeured Rolls Royce to meet him at the airport. Another bought a new motorcycle and when it wouldn't start one day he didn't even try to find out what was wrong with it. Instead he took a cab downtown and bought another one.

Beginning about the first part of October, the temperature so frequently drops below zero that one is spared the inconvenience of saying "minus." Whether someone says "18," "35," or "14," you automatically assume the temperature to be below zero.

During the summer I made a nuisance of myself asking others about working in the wintertime. I learned what kinds of arctic gear are recommended, and by the end of September I had purchased about $700 worth of clothing. I have a good pair of "bunny boots," so-called because of the relatively-large toe part of the boot. I have three kinds of long underwear, since each had its ardent supporters and I couldn't make up my mind. I have an insulated pair of coveralls - from a company called Refrigi-wear - which cost about twice the price of normal insulated coveralls. I have a $175 down parka complete with a fur ruff on the hood, made of "genuine Canadian prairie coyote." I don't wear it very much because I sweat in it at 35 below and also because I don't want to spill diesel fuel on such a prized possession.

I began to learn the techniques of staying warm. Don't wear cotton next to your body; try not to wear it at all. Wool, albeit itchy, does not make you cold when it gets wet. Make sure your socks are absolutely clean and dry - change them twice a day if need be. Wear a beard, even though they are not recommended in orientation because "beards make it more difficult to detect frostbite." Don't put nails in your mouth (a painful 30-below lesson). Stay away from anything wet, like water or fuel, as if it were the plague. Try to keep your facemask dry because the condensation will freeze it to your beard. One can never feel very comfortable in subzero tempera- tures. What you gain in keeping yourself warm is lost in more frustration and reduced mobility in doing the work.

Sometimes, though, the low temperatures could be fun. One brisk morning - a temperature of 35 below was proclaimed in the mess hall, where each camp in winter posts the temperature, wind speed, and wind chill - I was able to break the wooden handles of three sledge hammers. Wood becomes brittle at such temperatures, and although I realized this, I rather liked the idea of being so strong. Another activity I enjoyed was football or keepaway at the end of the day. Being bundled up in pillow-like clothing makes it easy to tackle and roughhouse without much fear of being hurt.

One frustration of working in the winter is the lack of light. At one camp to which I was assigned, Franklin Bluffs, the sun was down from Thanksgiving to January 15. Lighting facilities are necessary wherever work is being done.

Another frustration is trying to keep the equipment running. The struggle of men and machines against the elements is very real at 60 below. Although equipment is supposed to be kept running 24 hours a day, it stops for various reasons. Then one must construct a makeshift shelter, usually a parachute, and put a Herman Nelson heater (renowned in arctic climates for dependability) inside to bring the temperature up so the vehicle can be repaired and restarted.

Although I've worked on the line for six months, I still enjoy receiving newspaper clippings from an aunt in Peoria, Illinois, about what it's like working on the pipeline - about the frontier atmosphere and the gusto which prevails.

The writers don't realize that all the action is in Fairbanks, where pipeliners returning from the North Slope are celebrating and trying to drink the slope off their minds. That's where you'll find the bars, booze, gambling, high rollers, boomers, and "painted ladies." Probably the most excitement I've experienced working on the pipeline is meeting and talking with people who think it's an exciting job. My monologue, laced carefully with bits of profanity and East Texas colloquialisms, is beginning to sound pretentious.

Say, you ever hear about the road going through the middle of the Amazon? Yep, the Trans Amazon Highway. Now, that may be one place that could be termed a new frontier. Hell, I'd believe you if you said that was exciting....

Kenneth A. Johnson '75, whose accomplishments at Dartmouth included building his own log cabin in Thetford (A Place in the Country, January 1975) and graduatingwith honors six months early.,worked on the pipeline from June toDecember of last year. He returned toAlaska in late January.Larry Johnson (no relation) is an artistwho works in the wintry wastes of NewHampshire.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureGod and Man at Dartmouth

March 1976 By DAN NELSON -

Feature

FeatureA MEMORANDUM

March 1976 By McF. -

Feature

FeatureOPTIONS & ALTERNATIVES

March 1976 By D.N. -

Article

ArticlePeople & Places

March 1976 By JACK DEGANGE -

Class Notes

Class Notes1974

March 1976 By STEPHEN D. SEVERSON, JACK E. THOMAS JR. -

Class Notes

Class Notes1919

March 1976 By WINDSOR C. BATCHELDER, CHESTER W. DeMOND

Features

-

Feature

FeatureToro's President

DECEMBER 1966 -

Feature

FeatureA Recent Interview with Ernest Martin Hopkins' 01

APRIL 1991 -

Cover Story

Cover StoryWEBSTER’S TOP HAT

MARCH | APRIL 2014 -

Feature

FeatureTruckin' from the Meat Bar

July 1974 By JOHN GANTZ -

Feature

FeatureThe Dinan Decade

OCTOBER, 1908 By Shelby Grantham -

Feature

FeatureDartmouth's Medical Opportunity

October 1960 By WARD DARLEY