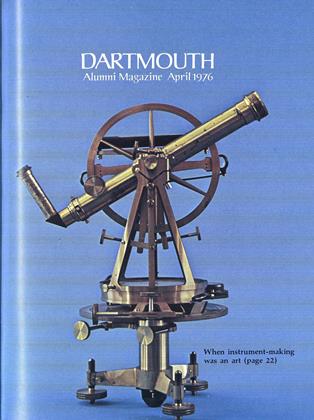

THE 18th century highboys of Benjamin Randolph's Philadelphia studio or the roadsters of the Isotta-Fraschini works in Milan have no parallels in today's world of furniture and motorcars. And rarely do modern scientific devices have the appeal and attractiveness - the artfulness - of the old hand-crafted instruments. The samples on these pages and the cover, photographed recently by Adrian Bouchard, are drawn from the College's collection of instruments acquired in the 19th century, when instrument-making was an art and when Dartmouth's scientific curriculum reached maturity.

Because of his meager supply of scientific apparatus for the course in natural philosophy of 1776, tutor Bezaleel Woodward frequently must have drawn Upon his practical experiences of weighing with a steelyard, of surveying and measurement with Wheelock's graphometer and Gunter half-chain, or of determining solar time by :neans of the dial presented to Wheelock in 1773. The pair of 18-inch globes and solar microscope, mentioned by Dr. Jeremy Belknap in his diary of 1774, would have aided him in teaching geography and astronomy and in revealing the wonders of the subvisible world. No other instructional devices are listed in the records. We can only surmise that none of note existed. Missing were such indispensable items as an air pump with accessories, an electrostatic friction machine, a set of mechanical powers, and an astronomical telescope. The College would acquire these and a few other devices during the next decade and add to them intermittently in succeeding years.

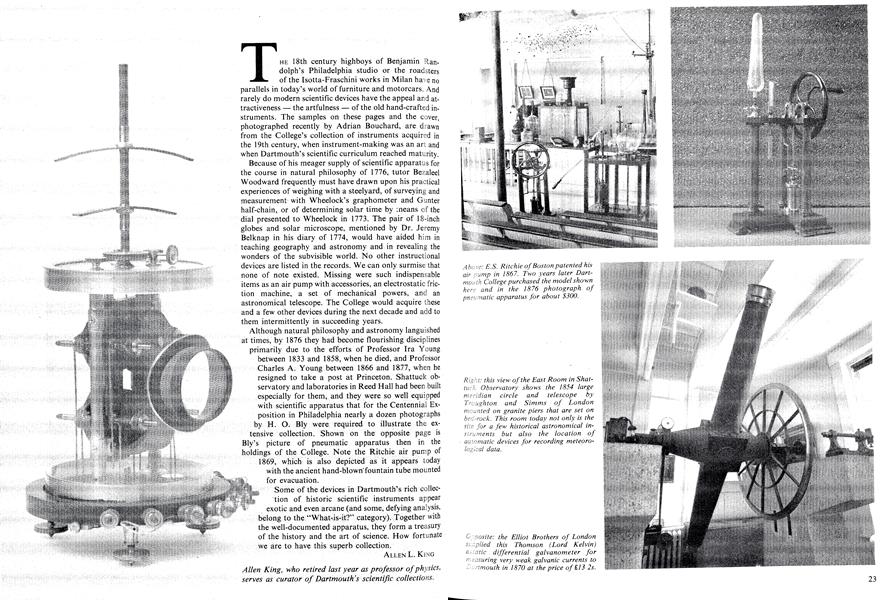

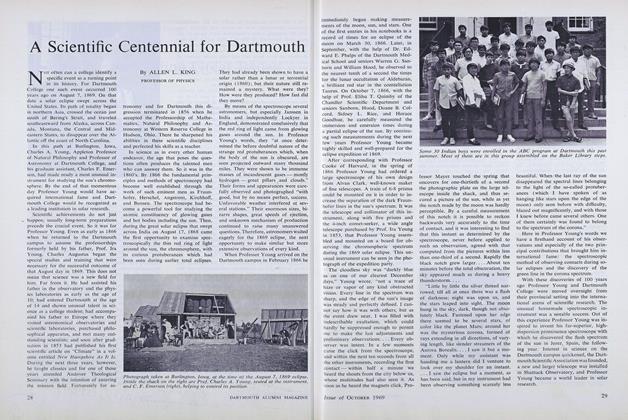

Although natural philosophy and astronomy languished at times, by 1876 they had become flourishing disciplines primarily due to the efforts of Professor Ira Young between 1833 and 1858, when he died, and Professor Charles A. Young between 1866 and 18.77, when he resigned to take a post at Princeton. Shattuck observatory and laboratories in Reed Hall had been built especially for them, and they were so well equipped with scientific apparatus that for the Centennial Exposition in Philadelphia nearly a dozen photographs by H. O. Bly were required to illustrate the extensive collection. Shown on the opposite page is Bly's picture of pneumatic apparatus then in the holdings of the College. Note the Ritchie air pump of 1869, which is also depicted as it appears today with the ancient hand-blown'fountain tube mounted for evacuation.

Some of the devices in Dartmouth's rich collection of historic scientific instruments appear exotic and even arcane (and some, defying analysis, belong to the "What-is-it?" category). Together with the well-documented apparatus, they form a treasury of the history and the art of science. How fortunate we are to have this superb collection.

Opposite: the Elliot Brothers of Londonsupplied this Thomson (Lord Kelvin)astatic differential galvanometer formeasuring very weak galvanic currents toDartmouth in 1870 at the price of £13 2s.

Above: E.S. Ritchie of Boston patented hisair pump in 1867. Two years later Dartmouth College purchased the model shownhere and in the 1876 photograph ofpneumatic apparatus for about $300.

Above: E.S. Ritchie of Boston patented hisair pump in 1867. Two years later Dartmouth College purchased the model shownhere and in the 1876 photograph ofpneumatic apparatus for about $300.

This LeRoy-type electrostatic diskmachine with its prime conductor and theLeyden jar battery probably werepurchased about 1840 by Professor IraYoung from an American craftsman. Thedevice stands about five feet tall.

Professor Ernest F. Nichols purchased thishand-made demonstration balance fromA. Ruprecht of Vienna in 1899 for 217Austrian florins (equivalent to $88.43).

Allen King, who retired last year as professor of physics,serves as curator of Dartmouth's scientific collections.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureWORDS AND PICTURES MARRIED The Beginnings of DR.SEUSS

April 1976 By Edward Connery Lathem -

Feature

FeatureStrangers in the House?

April 1976 By RAYMOND L.HALL -

Feature

FeatureLap After Grim Lap, Note After Sparkling Note

April 1976 By DAVID M. SHRIBMAN '76 -

Class Notes

Class Notes1975

April 1976 By GILBERT F. PALMER IV, FREDERICK H. WADDELL -

Article

ArticleVox Clamantis et Clamantis; or College Bites Man

April 1976 By TERENCE R. PARKINSON '71 -

Article

ArticleIn Defense of Prejudice

April 1976 By DAN NELSON '75

ALLEN L. KING

-

Letters to the Editor

Letters to the EditorLetters to the Editor

December 1976 -

Letters to the Editor

Letters to the EditorLetters to the Editor

March 1980 -

Books

BooksCOLLEGE PHYSICS

July 1960 By ALLEN L. KING -

Feature

FeatureA Scientific Centennial for Dartmouth

OCTOBER 1969 By ALLEN L. KING -

Article

ArticleDartmouth Names on the Moon

MARCH 1971 By ALLEN L. KING -

Article

ArticleThe Toppled Towers of Wilder

JUNE 1973 By ALLEN L. KING

Features

-

Feature

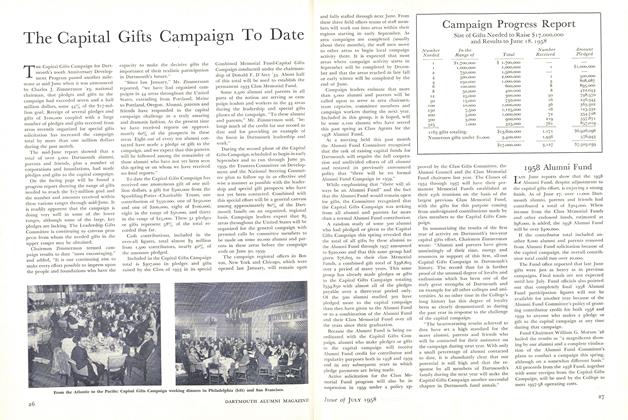

FeatureThe Capital Gifts Campaign To Date

July 1958 -

Feature

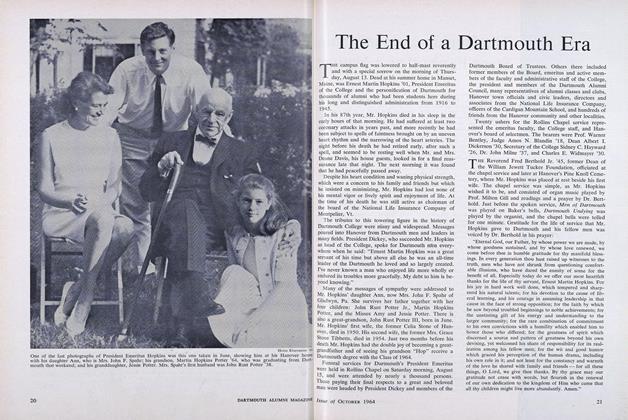

FeatureThe End of a Dartmouth Era

OCTOBER 1964 -

Feature

Feature1960 Commencement

July 1960 By D.E.O. -

Feature

FeatureFour-Star Summer

October 1959 By JIM FISHER '54 -

Feature

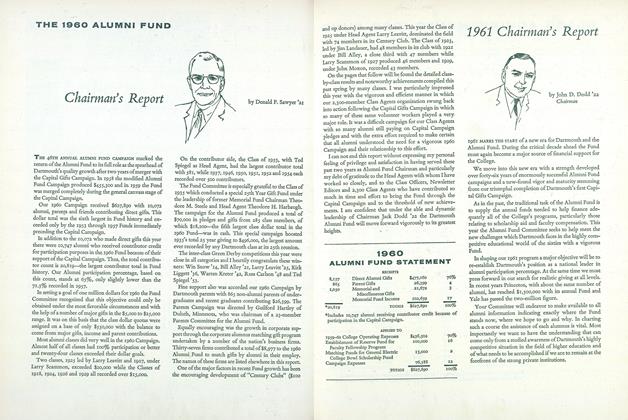

Feature1961 Chairman's Report

December 1960 By John D. Dodd '22 -

Cover Story

Cover StoryRobinson's Undoing

MARCH 1995 By Pam Kneisel '76