CONTRARY to common assumption, there is nothing wrong with intolerance, per se. it is a common and erroneous liberal notion, particularly prevalent on college campuses, that everything and everyone ought to be tolerated. Intolerance itself is the only thing that is not tolerated. Prejudice, of course, is anathema. It shouldn't be; in fact I think it has some real value. Disregard for a moment certain prejudicial connotations and consider one definition: "A preliminary or anticipatory judgment; an anticipation." Such judgments have their place as a sort of ballast. In four years of jettisoning old ideas and old opinions one easily gets carried away and throws over all standards.

A liberal education is incomplete unless one develops the proper sort of prejudices. I'm not advocating bigotry, but rather the development of a repertory of precepts for which there is some justification. Most of us are educated into a bland openness to everything, a pale willingness to concede legitimacy to almost any assertion. As a consequence, most of us are boring, possessors of the "low profile" when it comes to strong opinions.

I'm going to risk raising my head to offer a particular prejudice, namely that a liberal education, particularly one in the humanities, ought not to be a waste of time. Mine, for the most part, hasn't been, but some of its aspects I have found intolerable. I confess a prejudice, for example, against the format of class discussions. I am equally prejudiced in favor of lectures. This prejudice has as much to do with the nature of professors as it does with the nature of students.

I find it very difficult to remain indifferent to the fact that my time, money, and attention are being wasted in the occasional course in which a professor has no idea, at the beginning of the hour, of anything he's going to say or of the conclusion, if any, he might stumble upon at the end. The usual ploy of the lazy, indifferent, or otherwise incapacitated teacher in this position, as often tenured as not, is to conduct a discussion.

He asks a vague question. The usual response from his students, particularly at the beginning of the term, is dead silence. The teacher rephrases the question, rendering it a shade more obscure. More silence. The silence becomes embarrassing, unbearable. Finally someone speaks. Usually it is someone in the front two rows. He or she doesn't answer the question, doesn't intend to, but offers in response a statement or counter-question more obscure, if that is possible, than the ambiguity mumbled by the professor.

The professor is at an advantage in this situation. Most students are convinced that he is smarter than they. It isn't a question of his superior intelligence, only of his more extensive experience. The somnolent majority, slouched in the back of the room, assumes something important is being said. Several students take notes, underlining them perhaps. My freshman year, in classes of this sort, I regarded my ignorance with continuous amazement. Not being able to understand the mentor's esoteric subtleties, I used to resort to searching my neighbor's notebook for content for my own.

This situation is a source of great satisfaction to most parties concerned. Nothing in the way of effort is required of anyone, except for the effort of staying awake. A professor only needs an earnest facade coupled with an off-hand manner, a few stock witticisms, and the ability to read, when all else fails, from an irrelevant source so rapidly as to be unintelligible. The vocal student in the front row gets to hear himself talk, about anything he wants, without being challenged by anyone. The silent majority is reinforced in the belief that college is a bore, that ideas are beyond grasp.

Occasionally, in a discussion class, the professor does have something to say. Usually he is misguided by the perverse notion that he ought not to say it in a lecture. He formulates a series of leading questions designed to elicit a desired response which will be the basis for another question. Students, sensing that the professor has something definable in mind, snap at the bait and fall in the trap.

Any response, no matter how reasonable, if not the particular answer required by the coach's game-plan, is ignored. Not only ignored but not comprehended. A few of the more perceptive players sense at the start what the conclusion will inevitably be, record it in their notebooks, and fall into a slumber which has every appearance of attention. The less perceptive, or the more dedicated, wallow their way, inch by inch, closer to the brimming trough of truth.

Near the end of the hour the pace picks up. The professor, now in the full glow of imminent success, may be prancing up and down in front of the class with all the enthusiasm of a cheerleader. "Give me a B!" he cries. The class shouts out, "B!" "Give me a U!" "U!" the happy reply. "Give me an L!"... "What's that spell?" Not much. The bell in Baker tower rings. The session is over. The salivating pack romps out, tails wagging, in the happy conviction that it is being educated.

I've exaggerated my case. In four years I've had few classes like these. Still, a few is too many. Don't misunderstand me. It isn't intelligent discussion I disdain. I have taken a few classes, conducted as or incorporating discussions, which have been excellent. The excellence was not so much a consequence of the topic (one professor claimed there was no such thing as a boring course or professor, only boring students) or a particular collection of students, as it was of the talent of the professor.

In each instance the professor began discussion with a pointed question. Any student responding with only a summary of the larger topic under consideration, or with reference to an only tangential topic, was put on the spot with the immediate interjection, "That wasn't what I asked. Do you want to begin again?" Any reply which inaccurately or witlessly cited a source for support was challenged by the demand, "Where do you find that in the text?" These classes demanded more in the way of preparation and lucid articulation than any others. A few students thought that the professor was antagonistic. Most of us cursed the work load. All of us learned something.

I'm convinced that few professors know how to teach well enough to be anything more than lecturers. A relatively poor teacher may still present a tolerable lecture. Few students know enough to know when they are being short-changed. In the continuous debate over who does or who doesn't get tenure and why, I hope the College pays as much attention to teaching ability as it does to scholarship. We should expect both.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureWORDS AND PICTURES MARRIED The Beginnings of DR.SEUSS

April 1976 By Edward Connery Lathem -

Feature

FeatureStrangers in the House?

April 1976 By RAYMOND L.HALL -

Feature

FeatureLap After Grim Lap, Note After Sparkling Note

April 1976 By DAVID M. SHRIBMAN '76 -

Feature

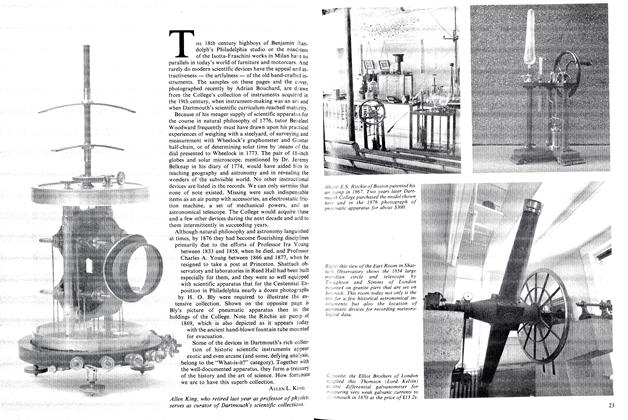

FeatureTHE 18th century highboys of Benjamin Randolph's

April 1976 By ALLEN L. KING -

Class Notes

Class Notes1975

April 1976 By GILBERT F. PALMER IV, FREDERICK H. WADDELL -

Article

ArticleVox Clamantis et Clamantis; or College Bites Man

April 1976 By TERENCE R. PARKINSON '71

DAN NELSON '75

-

Article

ArticleA Dorm Is Not a Home

December 1975 By DAN NELSON '75 -

Article

ArticleThe American Forum

January 1976 By DAN NELSON '75 -

Article

ArticleWarm Memories, Cold Pleasures

February 1976 By DAN NELSON '75 -

Feature

FeatureThanks to Daniel Oliver, A Gathering of Lovers

May 1976 By DAN NELSON '75 -

Article

ArticleNeeded: More Misfits

June 1976 By DAN NELSON '75 -

Feature

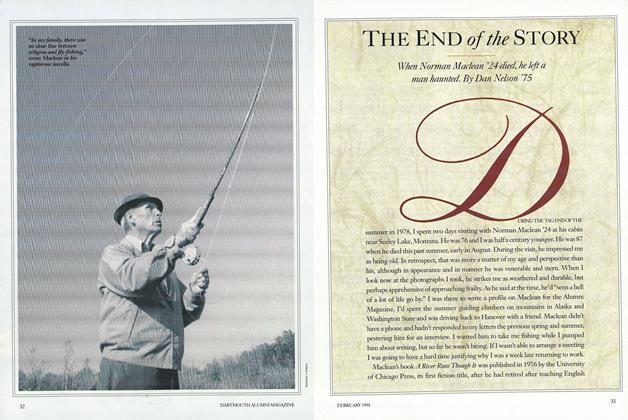

FeatureThe End of The Story

FEBRUARY 1991 By Dan Nelson '75

Article

-

Article

ArticleMr. Kimball's comprehensive and sympathetic account of his well-loved friend,

March 1918 -

Article

ArticleALUMNI ARE APPROACHED FOR LOUVAIN CONTRIBUTIONS

May, 1924 -

Article

ArticleTop Club President

November 1956 -

Article

ArticleWoodrow Wilson Fellows

April 1961 -

Article

ArticleBOARD GOES UP

MARCH 1964 -

Article

ArticleNew President of Skidmore College

JUNE 1965