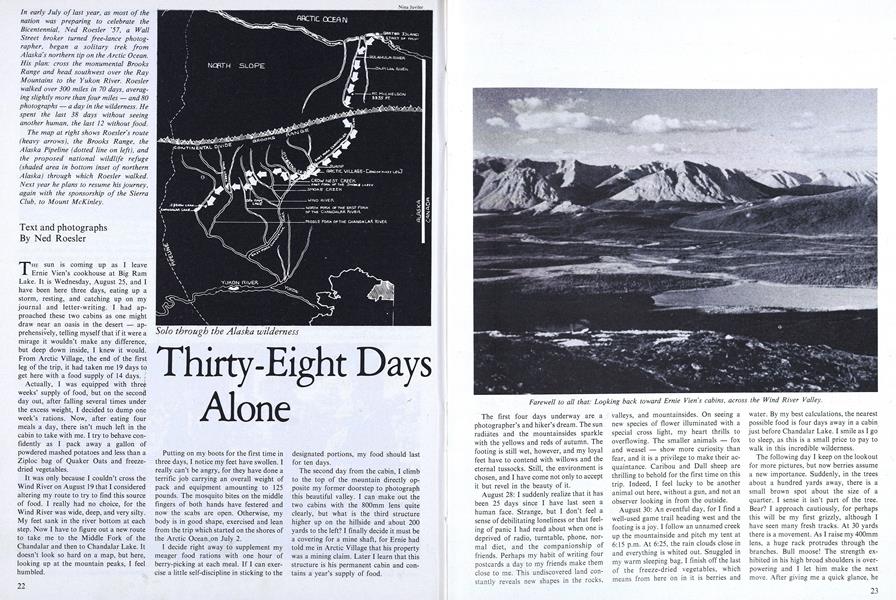

In early July of last year, as most of the nation was preparing to celebrate the Bicentennial, Ned Roesler '57, a Wall Street broker turned free-lance photographer, began a solitary trek from Alaska's northern tip on the Arctic Ocean.His plan: cross the monumental Brooks Range and head southwest over the Ray Mountains to the Yukon River. Roesler walked over 300 miles in 70 days, averaging slightly more than four miles - and 80 photographs - a day in the wilderness. Hespent the last 38 days without seeinganother human, the last 12 without food.The map at right shows Roesler's route(heavy arrows), the Brooks Range, theAlaska Pipeline (dotted line on left), andthe proposed national wildlife refuge(shaded area in bottom inset of northernAlaska) through which Roesler walked.Next year he plans to resume his journey,again with the sponsorship of the SierraClub, to Mount McKinley.

THE sun is coming up as I leave Ernie Vien's cookhouse at Big Ram Lake. It is Wednesday, August 25, and I have been here three days, eating up a storm, resting, and catching up on my journal and letter-writing. I had approached these two cabins as one might draw near an oasis in the desert - apprehensively, telling myself that if it were a mirage it wouldn't make any difference, but deep down inside, I knew it would. From Arctic Village, the end of the first leg of the trip, it had taken me 19 days to get here with a food supply of 14 days.

Actually, I was equipped with three weeks' supply of food, but on the second day out, after falling several times under the excess weight, I decided to dump one week's rations. Now, after eating four meals a day, there isn't much left in the cabin to take with me. I try to behave confidently as I pack away a gallon of powdered mashed potatoes and less than a Ziploc bag of Quaker Oats and freeze-dried vegetables.

It was only because I couldn't cross the Wind River on August 19 that I considered altering my route to try to find this source of food. I really had no choice, for the Wind River was wide, deep, and very silty. My feet sank in the river bottom at each step. Now I have to figure out a new route to take me to the Middle Fork of the Chandalar and then to Chandalar Lake. It doesn't look so hard on a map, but here, looking up at the mountain peaks, I feel humbled.

Putting on my boots for the first time in three days, I notice my feet have swollen. I really can't be angry, for they have done a terrific job carrying an overall weight of pack and equipment amounting to 125 pounds. The mosquito bites on the middle fingers of both hands have festered and now the scabs are open. Otherwise, my body is in good shape, exercised and lean from the trip which started on the shores of the Arctic Ocean on July 2.

I decide right away to supplement my meager food rations with one hour of berry-picking at each meal. If I can exercise a little self-discipline in sticking to the designated portions, my food should last for ten days.

The second day from the cabin, I climb to the top of the mountain directly opposite my former doorstep to photograph this beautiful valley. I can make out the two cabins with the 800mm lens quite clearly, but what is the third structure higher up on the hillside and about 200 yards to the left? I finally decide it must be a covering for a mine shaft, for Ernie had told me in Arctic Village that his property was a mining claim. Later I learn that this structure is his permanent cabin and contains a year's supply of food.

The first four days underway are a photographer's and hiker's dream. The sun radiates and the mountainsides sparkle with the yellows and reds of autumn. The footing is still wet, however, and my loyal feet have to contend with willows and the eternal tussocks. Still, the environment is chosen, and I have come not only to accept it but revel in the beauty of it.

August 28: I suddenly realize that it has been 25 days since I have last seen a human face. Strange, but I don't feel a sense of debilitating loneliness or that feeling of panic I had read about when one is deprived of radio, turntable, phone, normal diet, and the companionship of friends. Perhaps my habit of writing four postcards a day to my friends make them close to me. This undiscovered land constantly reveals new shapes in the rocks, valleys, and mountainsides. On seeing a new species of flower illuminated with a special cross light, my heart thrills to overflowing. The smaller animals - fox and weasel - show more curiosity than fear, and it is a privilege to make their acquaintance. Caribou and Dall sheep are thrilling to behold for the first time on this trip. Indeed, I feel lucky to be another animal out here, without a gun, and not an observer looking in from the outside.

August 30: An eventful day, for I find a well-used game trail heading west and the footing is a joy. I follow an unnamed creek up the mountainside and pitch my tent at 6:15 p.m. At 6:25, the rain clouds close in and everything is whited out. Snuggled in my warm sleeping bag, I finish off the last of the freeze-dried vegetables, which means from here on in it is berries and water. By my best calculations, the nearest possible food is four days away in a cabin just before Chandalar Lake. I smile as I go to sleep, as this is a small price to pay to walk in this incredible wilderness.

The following day I keep on the lookout for more pictures, but now berries assume a new importance. Suddenly, in the trees about a hundred yards away, there is a small brown spot about the size of a quarter. I sense it isn't part of the tree. Bear? I approach cautiously, for perhaps this will be my first grizzly, although I have seen many fresh tracks. At 30 yards there is a movement. As I raise my 400mm lens, a huge rack protrudes through the branches. Bull moose! The strength exhibited in his high broad shoulders is over- powering and I let him make the next move. After giving me a quick glance, he ambles off, keeping the trees between us. Quickly leaning my pack against a tree, I start to follow this magnificent creature. Crack! I jump as his mate crashes through the underbrush. I trail them by sight for over a half mile until they disappear over a small hill. I never get a clear shot of them, but seeing these huge animals underway will do by itself for now.

Making my way back to my pack, under threatening storm clouds, I suddenly feel in my stomach that the place where I left it won't be so easy to find. I had marked the location by a clump of three trees, but now clumps of three trees appear all over the place. After criss-crossing a quarter square mile for the fifth time, a voice from my childhood sounds: "Ned, look where it can't possibly be!" And there it is!

That evening I am wet and cold from walking in the rain, and, more to the point, from crossing the Middle Fork of the Chandalar. There had been no difficulty, and, as I slip into my sleeping bag, I still marvel at the rare opportunity to cross this virgin land. For me, this trip is the culmination of a boyhood dream to see Alaska; to find out first-hand the meaning of "North of the Arctic Circle"; to see the North Slope; walk through the Brooks Range; and wander across the tundra. It is a chance to be in true wilderness with no traces of man, where the animals, birds, and plants are sovereign. Even without food, my heart still beats excitedly upon seeing the two moose or coming upon a tiny new plant at my feet.

True, the mosquitoes have been omnipresent, the tundra practically unwalkable by any standards in the "Lower 48," but my heart is .soaring. How often does one get the opportunity to be out in the wilds alone for such a long time? This is a chance to assess metaphysical distances - where one has come from and where one is going. For most of us, such a trip is cast aside with the comment: "I" would love to go, if I had the time" or "Maybe when I retire."

September 1: 28 days without seeing another human being. The camera motor-drive is on the blink, so I open up the small compartment on the back and scratch the metal plates with my knife. It works.

My ETA could be three days hence, but the tundra has taught me to be positive and then multiply by two or three. I start to think of the bounteous meals that were served to me by Nina in the Indian settlement of Arctic Village, where I ended the first leg of the trip after 26 days. My senses conjure up that first dinner of three giant pork chops, three bowls of rice, three helpings of vegetables, ten biscuits, five mugs of tea, and three servings of fruit compote.

Thinking of my present predicament, I know the first question everybody will ask: "But how did you run out of food?" Best answer: a miscalculation of the number of miles I can walk in a day. This is certainly true, for no one from the Lower 48 can imagine what it is to wander among the ubiquitous tussocks.

Second, the rivers and the creeks run swift and deep and often have silty bottoms. Rarely does a traveler get across the first time, and the Wind River held the record for me - three days.

Third, I never let a photograph go by. A picture of a small plant might take an hour as I use different lenses and photograph it at various distances and from different angles.

Finally, I am carrying 125 pounds, counting pack, boots, clothing and equipment. The 800mm lens when assembled is about a yard long and weighs close to ten pounds. This lens is backed up by four others, including an 8mm f2.8 fisheye. The two camera bodies, the motor-drive, plus 110 rolls of film add up.

Right now, I have to accept the fact that I am going to come off this second leg with a very lean body. Since the start of my unintentional berry fast, my thoughts wander from the junk food one claims he never eats to the good restaurants visited during my Wall Street days.

This evening I see a seaplane disappear behind the trees several miles ahead. My hopes for food soar with the plane and then plummet precipitiously as the plane reemerges from what must have been a lake and then continues south. Now a decision has to be made. Should I stick to the hillside going down the Chandalar Valley or walk a mile to the west and follow a creek up into the mountains? Both routes lead south, but it is a question of which will be the easier walking and where I will stand the best chance of coming across a hunter or, if necessary, be able to signal a plane. After much thought, I choose the valley.

Evening of September 3: I put on my ski clothing before slipping into the sleeping bag. My hands, even with gloves on, are cold for the first time. Perhaps the loss of weight is beginning to effect the insulative capacity of my body. Rather than ponder this possibility, I concentrate on yesterday's successful crossing of Yours Creek after trying for six hours. I have to admit, though, that winter is in the air, and I know full well that the Arctic can get its first big snow any time around the middle of this month.

September 5: Up at 8:35. Tent frosted on the outside and the clothes lying on my pack in the tent are frozen stiff. My boots have a white glaze on them, so I know from now on they must be wrapped in a stuff sack and put in my sleeping bag at night. It takes me a half hour to push my feet into them this morning. Getting up from my first rest stop, I start to black out and let myself drop to the ground as I did yesterday. It is no longer a one-time occurrence, and I have to admit to myself that my body might be trying to give me a signal. Finally making it to a standing position, I am convinced that one must learn to take the good and the bad in life and go one's own pace. Even though I know that time is critical from here on, I resolve not to miss a picture and to let my body rest when it wants, for panic or overtiredness will sap whatever strength I have left.

There is good berry-picking today, but the blueberries are beginning to splay as soon as one touches them, so the times when I could pick four or five at once are gone. Make camp at 6:30 p.m. and hang wet clothes and the damp sleeping bag and tent out on a line as I write in my diary. It strikes me that from now on I must force myself to drink at least two quarts of water a day. Today it has been cold and I haven't had but a few sips. The fingers with the mosquito bites have lost their ugly scabs, replacing them with transparent layers of skin. My right thumb still has tape over it as the deep crack across the top refuses to heal. I take pictures of the drying clothes before going to sleep.

Monday, September 6: Awake with temperature of 37° in tent. The top half of the water in the canteen is frozen. Had delicious blueberry pick before starting out. I cross Kern Creek and start up a 4,000-foot elevation, supposedly my last before I see Squaw Lake Valley. From there I have only to climb 5,000 feet to McLellan Pass and then descend to Chandalar Lake and my food supplies!

Going uphill is tough with the willows and the tussocks. Three things that add to my enjoyment in the wilderness are either now non-existant or severely limited: food, photography, and writing - both postcards and in my diary. Food is berries when they can be found; photography is curtailed, for there have been no ungulates since the two moose, and the ducks must be making their way slowly south; writing is limited to only the most critical observations and film notations, for the three remaining pencils are reduced to stubs.

Tuesday, September 7: Temperature is 30° inside tent. I wear my ski suit for the first time underway. I am cold. I photograph Kern Creek to my rear as well as the route I have been following along the Middle Fork of the Chandalar. I am still not sure in retrospect whether it wouldn't have been easier to skirt this promontory to the east and then enter Squaw Lake Valley, but such a decision would depend on unknowables: wetness of the terrain, tussocks, availability of berries, etc. It is too late to worry about such matters as I am over halfway to the top. By late afternoon I reach what I think is the top, but upon looking south, I see an alpine valley backed by tall masses of rock to the south. I can't believe it!

I am really confused - I should be looking down on my expected valley. Complete dejection overcomes me as I sit down with compass and map to figure out where I am going. My head says I should head due south and try to follow one of the narrow openings between the masses of rock, but my compass and map say that south is 90° to the right from where I am looking. I decide to hike down into the valley and sleep before making a decision.

Feeling deflated, I remember what my mother used to say to us children when things seemed gloomy and without solution: "Remember, tomorrow will be a better day!" Crawling into my tent, I stare at the wintry dark clouds racing by the descending sun.

Wednesday, September 8: Awake at 7:00 to hear a slightly familiar sound in the air. With trepidation, I raise my hand to the roof of my tent and feel a heavy mass slide to the ground. Springing to the front window of the tent, my dreaded suspicion is confirmed - snow! There are three inches already, with more flakes swirling to the ground in earnest, whiting out my alpine valley completely. The mountain walls are invisible. With the visibility so poor, I have no choice but to wait the storm out. When the snow turns to rain at 2:00 in the afternoon, an official rest day is declared. The rain continues until five o'clock, and I take several naps and think about friends back home, re-design my apartment, and envision all the restaurants I would love to visit, if I had the money.

Thursday, September 9: Awake at 9:30 to find the sun free of clouds. I have eaten nothing for 36 hours because the berries are covered with snow. Starting out, I feel ebullient seeing the sun, but with the snow cover, I don't know if I am going to fall through to a tiny streamlet, into a hole, or stumble over a small tussock. Getting up from my first rest stop, I start to black out again. On the next four tries exactly the same thing happens. How can I finish this trip if I can't even regain my feet?

At this point I know there is a distinct possibility that I won't make it. My mind flits back to Moses Sam, a veteran hunter in Arctic Village, who, when I explained I wasn't carrying a gun, said he and his wife Ginnie would remember me in their prayers. Not wanting to waste the energy thinking about not making it out, I decide just to take it easy and do the best I can. This time I am able to get to my feet. Starting up the ridge, I don't feel ready to depart from my friends and this life.

As the ridge seems determined to hang in the distance, I remember an entry I made in my diary as I entered the Brooks Range from the North Slope. I had photographed some of the 110,000 caribou in the Porcupine herd, Arctic fox pups, a family of weasels, birds, ducks, wildflowers, miniature plants, and the spectacular backdrop of the majestic Brooks Range. I was ecstatic about this unique opportunity and wrote that I could die for photography. Perhaps so, but I am going to do my best to make it out.

As I make for the top of the ridge, my wool knickers keep slipping to my kneecaps. Holding them out from my waist, there is a four-inch gap. Maybe this is why I feel the cold so much and my body insists on blacking out. Upon reaching what seems like the crest of the ridge, my heart stops. Instead of looking down into the expected valley, I am gazing out to snow-covered peaks stretching far into the distance. I might as well be in the Himalayas. The shock is so great that I feel like crying. It means that I really haven't made any progress at all and that I am miles from Chandalar Lake. However, this panorama is probably the most spectacular mountain scenery I have ever seen. I try to photograph it, but my hands are so cold that I can't depress the shutter. Disappointed, I walk forward to check out the terrain. After a hundred yards, I come over a rise and there down below is Squaw Lake Valley!

I let out a big yell and run part-way downhill just to give vent to my joy. I wonder as I say to myself: "I knew you would make it, if you could just keep going!" Once below the 3,000-foot level, the snow covering disappears and I dive for the first blueberries in sight. Even though they are covered with frost and still splaying, it helps psychologically to be able to taste something. My hands have very little feeling in them, so this effort might be counter-productive, but it feels good to sprawl out on the ground and taste the berry juices.

Making camp that evening, I gaze across the valley to McLellan Peak rising majestically from the valley floor. A decision will have to be made: to go up 5,000 feet over this pass or skirt the mountain by proceeding due west past Squaw Lake and then south to Chandalar Lake. It really depends on which cabins shown on this 20-year-old map might be inhabited or, if not, which ones might contain provisions. Even though the pass is covered with snow above the 3,000-foot level, it is the shorter route and the Chandalar Mine on top should still be in operation. If I were to black out completely at the higher altitudes, it could spell trouble. However, the map shows a cabin at the base of the mountain, so I decide to head for it.

Friday, September 10: The sun is shining brightly, which must be a good omen. I keep to the west side of the valley. The going is tough with the willows, firs, and the wet footing over and around the tussocks, but my spirits are up. My pencils are completely unusable at this point, so there is no more writing of any kind.

Saturday, September 11: I reach Slate Creek 30 minutes after starting out, which is my signal to head across the valley toward the mountain. As I approach a small lake, I am suddenly stopped by a familiar drone. Looking across the valley, I see two low-flying red planes coming from the direction of Squaw Lake. Food! My heart jumps as I realize their link between me and something to eat. The coloring of the aircraft suggests rescue planes, and I suddenly remember the agreement I had made with my backup man at the University of Alaska. "Give me three weeks on each leg, plus two weeks in case the going is slow or I get immeshed in some photographic study, and then notify the people at my food pickup point that I am overdue." Quickly calculating the elapsed time, I am three days past that grace period of two weeks.

I instinctively rip out a package of flares. Unscrewing the cap and putting my finger through the pull chain that will send a bright orange ball 200 feet skyward, I think to myself: "But Ned, you are still walking." Puff! The planes don't see it. Within seconds, another flare streaks skyward and this time the plane nearest to me peels off and circles overhead. He dips his wings and rejoins his partner, flying east.

An hour later my friend reappears, circles once, and drops what looks like a McDonald's bag. I know it is going to take more than a Big Mac to get me over the mountain, but I sprint like a crazy man after the bag, which is bouncing over the tundra.

Ripping the package open, I see what look like chunks of sausage. Not exactly what I had hoped for,'but my nearly frozen hands dive for a morsel. Chomping down on the first piece, I hear a cracking sound as my teeth hit something hard. What is happening? I take a closer look at the item in my hand. A rock! Is this supposed to be a joke? I am furious until I see some scribbling on the package. The rocks have been put in to weigh the bag down. The message gives instructions for summoning help by way of a helicopter located at Chandalar Lake. Raising my left hand and walking down to the lake gives the pilot the signal that this is exactly what I need.

As the plane flies off a second time, I know my days of starving are over. All of a sudden my body relaxes and I feel cold. The next hour and a half seem endless as I pace up and down to keep warm." Suddenly, I hear the sound of what seems like a winged plane. But where is the helicopter? It turns out to be a turbo helicopter, and what a beautiful sight to see the pilot set her down. Taking pictures of this event, I think of the coincidence: I started and ended my trip in a helicopter.

After a ten-minute ride, the helicopter sets down at the Chandalar Lake field camp of some 11 geologists from Resource Associates of Alaska. They are my first human contact in 38 days! After a brief introduction, the helicopter pilot suggests that I might wander over to the camp kitchen. I need no coaxing.

My nostrils come alive as I pull back the flap to the cook tent. My hands, instinctively reaching for a bag of chocolate cookies, are pried loose by Susie the cook. She explains that anyone who has lost as much as 50 pounds has to be brought back slowly with proteins. To remove me from temptation, she asks me to sit in the middle of the tent. And so I begin to eat again - eggs and fish now - and steak and fruit later that evening.

That night I am flown down to the landing strip to pick up my mail forwarded from Fairbanks. It is a unique experience to be sitting up by a lone lantern in a warm tent reading letters until three o'clock in the morning. As I snuff out the lantern, my mind drifts back to the 70 days I had just spent north of the Arctic Circle. The pictures of caribou, fox, wolf, weasel, birds, ducks, wildflowers in this indescribable land swim before my eyes. Drifting off to sleep, I'm glad to be alive. I hope, too, that Alaska's wilderness will not be just a catchword for today, but continue as a national treasure to be preserved for tomorrow.

Solo through the Alaska wilderness

Farewell to all that: Locking back toward Ernie Vien's cabins, across the Wind River Valley.

An Arctic fox (above), roused from a deepsleep, peers at the camera from a distanceof 16 feet. At the start of his journey, nearHulahula Valley, Ned Roesler (right)photographed himself by timed exposure.

Opposite (fisheye lens): "This undiscoveredland constantly reveals new shapes.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureScience and Technology Under Siege

September | October 1977 By Thomas Laaspere -

Feature

FeatureDartmouth Passages

September | October 1977 By Marshall Ledger -

Feature

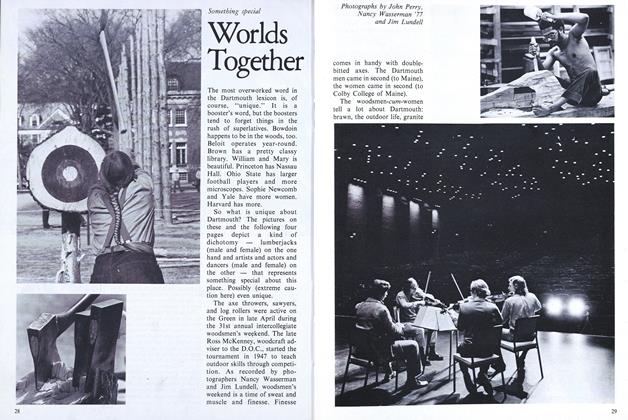

FeatureWorlds Together

September | October 1977 -

Article

ArticleFanciers

September | October 1977 By BRAD HILLS '65 -

Class Notes

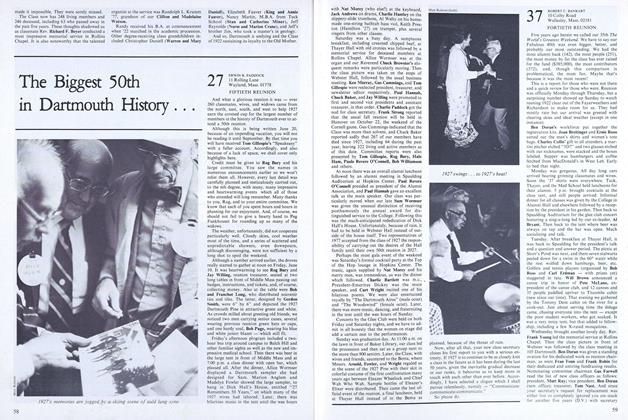

Class Notes1927

September | October 1977 By ERWIN B. PADDOCK -

Class Notes

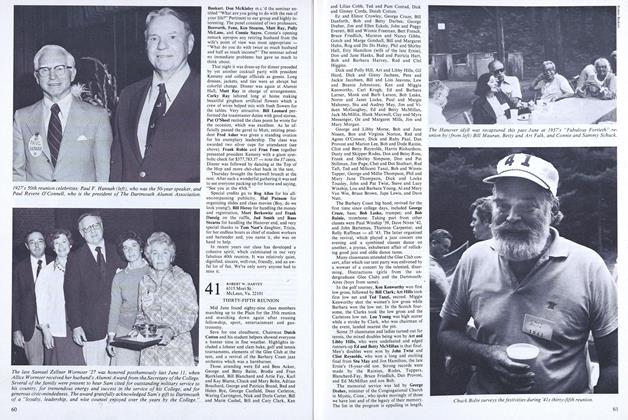

Class Notes1941

September | October 1977 By ROBERT W. HARVEY, STEVE WINSHIP

Features

-

Feature

FeatureBoat Rocker

OCTOBER 1966 -

Feature

FeatureJUNE IN HANOVER

JUNE 1990 -

Feature

FeatureTHE WORLD OF DONALD HYATT

January 1961 By CLIFFORD L. JORDAN JR. '45 -

Feature

FeatureConquest of the Antarctic

June 1957 By DAVID C. NUTT '41 -

Feature

FeatureOUR PASSIONATE PREFERENCE

FEBRUARY 1991 By Joseph D. Mathewson '55 -

Feature

FeatureValedictory to 1957

July 1957 By PRESIDENT JOHN SLOAN DICKEY