Thinking positively:

BECAUSE science and technology lack a sensitive and flexible contact with the outside world, they have spread ugliness over the earth, constructed cities which are degrading, turned workers into automatons, and invented diabolic forces of destruction. Science has also distorted the human condition by perpetuating the myth of the golden age. My colleague Peter Bien, of the Dartmouth English Department, made these charges in the October 1974 issue of the ALUMNI MAGAZINE. His article, "More than a beast, less than an angel," took a kind view toward the humanities and a generally critical one toward science and technology.

The charges left me in a state of mind which was critical and, to use a word from the article, "reflexive" at the same time. Critical, because my colleagues and I felt that science and technology had not received a completely fair and understanding treatment; "reflexive," because the article raised some fundamental questions to which I, a person from the physical sciences, did not have a clearly formulated answer.

Since that time, I have tried to order my own thoughts on some of Peter Bien's points. Because of my long-standing interest in languages and literature, I have, in particular, tried to get a good idea of how humanists of the literary brand have felt about science and technology in the last couple of centuries when science was in the midst of rapid growth and technology became increasingly pervasive. I will use the results of this inquiry into literature to respond to the humanists' views concerning science and technology. My approach will be to conduct a kind of dialogue in which I refer to the pertinent material in literature, and then respond either with my own thoughts, or, if this appears more appropriate, in the words of some other person from the scientific community. I shall try to be totally honest to my own beliefs in this undertaking and let approbation and critique fall where they may - it will be seen that neither will fall exclusively on the same side of the fence separating what C. P. Snow has called the "two cultures."

IT is dangerous to make generalizations covering centuries in which the reactions of individual writers to science have been different and varied, but it appears that for about 100 years after the publication of Newton's Principia in 1687, many writers not only looked upon science with approval, but actually participated in its advancement. At that time, science was widely, regarded as a new, excitingly enlightening, but nonthreatening manifestation of the human spirit.

The comparatively harmonious relationship did not last. As the scientific point of view became increasingly dominant in the 19th century, and as the darker sides of industrial society became more apparent, the writers tended to withdraw themselves into a world in which science and its applications played only a peripheral role. In that more familiar world isolated from science and technology, the writers con- tinued to emphasize the exploration of the emotional and instinctive core of the human animal. It is as if the ever-changing technological outer world had provided the authors only with different stage settings in which to play out age-old human-interest stories involving love, hate, jealousy, ambition, generosity, greed, and courage. It is ironic that many humanists have turned against science because they consider it too "rationalistic," even though, as discussed in great detail by Alfred North Whitehead in his Science and the Modern World, reaction against the inflexible rationality of medieval thought was a key ingredient in the birth of modern science.

The preoccupation of the writers with nontechnical topics has had the consequence that science and technology do not constitute a major theme in the literature of the past 150 years. Still, many literary works of a high quality exist which comment more or less directly on science and its applications. Not surprisingly, writers have never presented a united front, and literature contains points of view which range from one extreme to the other. Some poets have praised science for enlarging the scope of human understanding and have been impressed by technology for creating a world of power, speed, and dynamism; others have protested vehemently against the "coldness" of science and the various real and imaginary ills of a technological society. There are also those who have taken a comparatively sympathetic view of the goals of scientific and mathematical inquiry, but have rejected the applications of science as manifested in an industrial society. On the whole, however, it appears that in the last 150 years or so the negative attitudes have outweighed the positive ones. The literary artists have tended to view science and its applications with resentment, suspicion, or outright hostility.

As to the views of literature concerning technology, poets from Wordsworth to Frost have resented it as an ugly, smelly, peace-disturbing and nature-destroying intruder. In his poem "On the Projected Kendal and Windermere Railway," Wordsworth exclaimed in 1844: "Is then no nook of English ground secure from rash assault?" - a question which has continued to echo with small modifications all around the globe with reference to the location of railroads, interstate highways, airports, nuclear power plants, oil refineries, paper mills. Writing at about the same time as Wordsworth, the French poet Alfred de Vigny stated in one of his best-known poems that man has mounted "this blind monster," "this smoking, breathing, and bellowing iron bull" too early. About 100 years later, in a poem entitled "The Egg and the Machine," Robert Frost gave expression to similar feelings of resentment, suspicion, and fear about technology, or more precisely, about the locomotive as a symbol of technology.

The image of technology as a threaten- ing intruder emerges not only in poetry but also in prose. For example, in LadyChatterley's Lover (1928), D. H. Lawrence refers to "wicked electric lights" which have "an undefinable quick of evil in them." The thoughts of the game-keeper, Mellors, appear to reflect Lawrence's own views:

The fault lay there, out there, in those evil electric lights and diabolical rattlings of engines. There, in the world of the mechanical greedy, greedy mechanism and mechanised greed, sparkling with lights and gushing hot metal and roaring with traffic, there lay the vast evil thing, ready to destroy whatever did not conform. Soon it would destroy the wood, and the bluebells would spring no more. All vulnerable things must perish under the rolling and running of iron ...

It is pertinent to point out that immediately after having written these lines, Lawrence thoughtlessly lets Mellors pick up his gun to go to a cottage to light a petroleum lamp. We know, as Lawrence undoubtedly knew but was apparently too biased to admit, that it takes technology to produce petroleum, gunpowder, and metal guns and lamps. Contemporary humanists are open to criticism for the same kind of inconsistency if they wash their hands and consciences of technology by rejecting it vehemently in words, but continue to accept and enjoy the goods and services technology provides.

My second response to Lawrence is at a much more personal level.

I grew up in surroundings which were at the technological level of rural America of about 100 years ago. Our home was heated by a huge wood-fired central oven; my mother did the cooking and the heating of water on a wood-burning stove; cold water was carried into the house in buckets after hand-pumping a well out in the yard; the long Estonian nights were dimly lit by kerosene lamps; my mother did all of her ironing using irons which were kept hot by charcoal (which gave off carbon monoxide gas); and horses provided the motive power in private transportation. Our house had, of course, no refrigerator or freezer (which made the preservation of food especially difficult in summer months), no vacuum cleaner, no washing machine, no clothes dryer - nothing in the way of modern household appliances. (By the way, we did not feel underprivileged because everybody else we knew, or were conscious of, lived the way we did.)

Anybody who feels that those were the "good old days" may wish to debate that assertion with my mother who survived all of the hard work - and the carbon monoxide gas - and is still living in Estonia. (I would like to mention that in addition to her household duties, she also served as the midwife of the region, helping hundreds of babies to be born in home surroundings without an attending physician.)

From the perspective of the people living in that society, the arrival of technology in the form of electricity was progress which had no evil connotation whatsoever. I still remember the night when we walked from room to room through the house, not by carrying a smelly and smoky kerosene lamp as before, but by switching electric lights on and off.

Actually, I could have kept myself out of the argument, and let some other writer respond to Lawrence's overcritical writings. In fact, in some of the poems of the 19th century the optimistic expectations concerning the "fruits of science" reached such heights that they are a source of embarrassment to present-day scientists and engineers. Two years after Wordsworth had protested against the railroad's encroachment on the peaceful English countryside, Charles Mackay wrote his poem "The Railways," in which he expressed the hope that by linking town to town and land to land, men would be joined in amity, and concluded with a burst of enthusiasm:

Blessings on Science, and her handmaid Steam! They make Utopia only half a dream; And show the fervent, of capacious souls, Who watch the ball of Progress as it rolls, That all as yet completed, or begun Is but the dawning that precedes the sun.

Alas, the decades that have passed since Mackay's sunny optimism have shown that rails can be used both for fostering friendships and for transporting war material, and that progress is a concept which is much more difficult to define and measure than was anticipated.

ONE probable cause of the falling-out between science and the humanities has been the detached and somewhat condescending attitude that science has developed toward man. Whereas literature has always tended to emphasize close-range subjective exploration of man, scientific inquiry has ranged far and wide, and the perspective provided by its findings has led to a constant demotion of our place in the universe. Science has, in effect, dethroned man from the unique and lofty position into which he had lifted himself in earlier times. We may still be the kings of the castle earth, but the study of man's evolutionary background has shown that we share our royal family tree with the monkeys, and our castle is but a relatively small chunk of rock and molten iron which circles a run-of-the-mill hydrogen furnace. As George Rombi has written in Dimensions of Science, scientific discoveries which used to be considered as conquests of the rational can now just as well be thought of as victories of the absurd for the reason that they strip human life of all transcending significance. The distressing view of the ultimate fate of man revealed by science is understandably unattractive to the humanists, and the bringers of bad tidings have never been popular. However, if the principle of searching for the truth were relaxed, the pleasant fairy tales would not return alone. As certainly as night follows day, they would be accompanied by fear, superstition, black magic, and all the other goblins of the human imagination.

It seems to me that the writers have not given science enough credit for its contributions to human enlightenment. Instead, they have complained bitterly about the demythification and the demystification of nature which has placed some restrictions on the traditional paths of the poets' flights of imagination. Edgar Allen Poe's "Sonnet to Science" (1829) is a good example of this complaint:

Science! true daughter of Old Time thou art! Who alterest all things with thy peering eyes. Why preyest thou thus upon the poet's heart, Vulture, whose wings are dull realities? How should we love thee? or how deem thee wise, Who wouldst not leave him in his wandering To seek for treasure in the jewelled skies, Albeit he soared with an undaunted wing? Hast thou not dragged Diana from her car? And driven the Hamadryad from the wood To seek a shelter in some happier star? Hast thou not torn the-Naiad from her flood, The Elfin from the green grass, and from me The summer dream beneath the tamarind tree?

My response to such complaints is that scientific interpretations of nature have indeed deprived us of the elves, nymphs, gods and goddesses of the woods, fields, mountains and meadows. However, to maintain that this has also removed the mystery from nature shows a lack of understanding of what science has or has not been able to reveal to the human mind. The mystery has not been removed - it has only been moved to a less superstitious and naive level.

For example, I have personally been involved in studies of the generation and propagation of radio waves with experiments placed in satellites and with apparatus set up at ground stations from Labrador to Antarctica. I must have written tens of thousands of words on what we have found out. But when I turn on my short-wave radio receiver and hear voices which originated in Europe only a small fraction of a second before, I feel like saying: Isn't this fantastic! Isn't this mysterious! The Nobel prize-winning American physicist Isidor Rabi recently observed:

My view of physics is that you make discoveries but, in a certain sense, you never really understand them. You learn how to manipulate them, but you never really understand them. "Understanding" would mean relating them to something else - to something more profound. But these basic things in physics can't be related to anything more profound. Everything has to be related to them. So in that sense you never really understand them.

As to the beauty of the world around us, I agree with Wordsworth that "the beauty in form of a plant or animal is not made less but more apparent as a whole by more accurate insight into its constituent properties and powers." The realization that one is looking at a system of some 100 billion suns does not necessarily detract anything from the beauty of the starry heavens on a clear winter night. To me at least, the sense of beauty is only increased by the awareness that I am not looking at a spherical crystal shell studded with twinkling Christmas tree lights but at something that by human standards is incomprehensibly vast and enduring.

I still have to respond to the charge of writers and other humanists that the scientific method is cold and inhuman, that it separates the subject (the investigator) from the object (the phenomenon). An eloquent exposition of the scientist's point of view on this was given by Steven Weinberg in the 1974 summer issue of Daedalus. In his article, entitled "Reflections of a Working Scientist," Weinberg responded to a suggestion of Theodore Roszak that research be subordinated "to those contemplative encounters with nature that deepen, but do not increase knowledge." (Roszak has also stated that "the ideal of scientific objectivity is a common disease of alienation.") I quote part of Weinberg's response:

My answer is that science cannot change in this way without destroying itself, because however much human values are involved in the scientific process or are affected by the results of scientific research, there is an essential element in science that is cold, objective, and nonhuman.

At the center of the scientific method is a free commitment to a standard of truth. The scien- tist may let his imagination range freely over all conceivable world systems, orderly or chaotic, cold or rhapsodic, moral or value-free. However, he commits himselt to work out the consequences of his system and to test them against experiment, and he agrees in advance to discard whatever does not agree with observation. In return for accepting this discipline, he enters into a relationship with nature, as a pupil with a teacher, and gradually learns its underlying laws. At the same time, he learns the boundaries of science, marking the class of phenomena which must be approached scientifically, not morally, aesthetically, or religiously.

One of the lessons we have been taught in this way is that the laws of nature are as impersonal and free of human values as the rules of arithmetic. We didn't want it to come out this way, but it did. ... If a correlation were discovered between the positions of constellations and human personalities, or between the fall of a meteor and the death of kings, we would not have turned our backs on this discovery, we would have gone on to a view of nature which integrated all knowledge - moral, aesthetic, and scientific. But there are no such correlations.... Nowhere [in the heavens] do we see human value or human meaning.

Note that in referring to science, Weinberg did not use the word "inhuman," which has a negative connotation, but the more neutral term "nonhuman." Weinberg's point of view thus appears to be one with which I am personally in sympathy - namely, that in themselves, dissociated from applications, scientific results are neutral.

OF COURSE, the important question arises whether it is realistic to consider scientific results apart from their potential applications. After all, our society if full of ambitious and in some cases even demented men and women, and the world is divided into selfish nation states which are always searching for new ways to increase their powers. In such a world the sound of explosions may well drown out a debate of whether or not a formula which permits the easy fabrication of dynamite is in itself "neutral."

In the recent play The Physicists (1962), the Swiss playwright Friedrich Dürrenmatt explores the conflict between the ideal of scientific freedom and the need for scientists' accountability and social responsibility. Dürrenmatt raises the question of how the physicists, as well as the nonphysicists, should behave in a world in which "it is impossible to adopt the ethical principle that one should remain an idiot" and yet in which it is also obvious that "thinking of a certain kind is dangerous - just like smoking in a gunpowder factory." While sympathetic to the dilemma that confronts the physicists, Dürrenmatt is more critical of the engineers for not being conscious of the broader implications of their work. One of the three physicists in the play says:

[As a scientist], I ... elaborate a theory about [electricity] on the basis of natural observation. I write down this theory in the mathematical idiom and obtain several formulae. Then the engineers come along. They don't care about anything except the formulae. They treat electricity as a pimp treats a whore. They simply exploit it. They build machines - and a machine can only be used when it becomes independent of the knowledge that led to its invention. So any fool can nowadays switch on a light or touch off the atomic bomb.

There are signs, such as the publication of a special report by the American Association for the Advancement of Science, that the whole scientific community is starting to become increasingly aware of the importance and the complexities of the issues relating to the scientists' freedoms and responsibilities. The current debate concerning the advisability of research on recombinant DNA also indicates that these questions would have surfaced sooner or later even in the absence of the guilty conscience about Hiroshima and Nagasaki. (The research in question involves the joining of genetic material DNA of two different living species. The resulting recombinant DNA can then be inserted into bacteria for reproduction. Fear has been expressed that if research of this type is pursued, it could result in the creation of new and highly dangerous bacteria.) Indeed, the statements of some prominent scientists start to sound as if they were written by Dürrenmatt. As Robert Sinsheimer, the chairman of the biology division of Caltech, recently said, "To impose any limit upon freedom of inquiry is especially bitter for the scientist whose life is one of inquiry; but science has become too potent. It is no longer enough to wave the flag of Galileo."

Sinsheimer may be magnifying the dangers of continuing the research on the recombinant DNA, but it could be argued on his behalf that in such matters it is prudent to be cautious. Also, the experience with nuclear research has shown that the scientists tend to be rather nearsighted concerning the likely consequences of their work. The key persons who were working on the experimental and the theoretical research which made possible the construction of the atomic bomb apparently did not believe as late as 1939 that anything practical, good or bad, might come out of their work. During a seminar discussion of the possible practical applications of his discovery, Otto Hahn, the German scientist who discovered nuclear fission, is reported to have exclaimed, "Das kann doch Gott nicht wollen!" "But God cannot possibly want this!"

What actually happened shows two things: 1) We cannot rely on God for keeping research harmless; 2) at least occasionally, writers have a better imagination and greater vision than the scientists in such matters.

The first point has been proven by history. Concerning the second point, H. G. Wells used the term "atomic bomb" at the beginning of this century. In his book World Set Free he staged an atomic war, although even his lively imagination fell far short of what the Americans and the Russians could actually unleash half a century later. If a writer could visualize an atomic war in about 1910, why did the scientists themselves not start to think about the bomb for 30 more years? Is it an indication that scientists put too much of their energy and imagination into advancing the immediate frontiers of knowledge, and do not spend enough time thinking about where the frontier may lie a couple of decades later? Do we have enough Sinsheimers even now? If not, should we perhaps, as an added insurance, pay more attention to the views of writers and other humanists?

I personally feel that we should indeed pay the views of the humanists greater heed. From the short dialogue we have just had with literature, we can conclude that at worst an exchange of views with the humanists will do the scientific-technical community no harm. If the humanists are on firm ground, it should not hurt them, either. It is also possible that an understanding exposure to the humanists' point of view might not only make us more sensitive to human concerns, but perhaps even increase our vision so that we can recognize some new dangers that may be lurking ahead.

The humanists, in turn, should keep in mind that it is scientific knowledge applied through technology that clothes us in new fabrics; feeds us with food produced in a highly mechanized and chemically supported agriculture; provides us with the means of information and entertainment through the printed word, movies, radio, long-playing records, and television; gives us the opportunity of almost instant communication with our next-door neighbor and the distant parts of the world; tremendously increases our capacity to analyze difficult problems with the help of computers and electronic calculators; produces the vehicles of transportation that move us and our food and goods on land, sea, and in air. Technology also helps to cure us from serious disease in hospitals full of sophisticated machines and instruments, or better yet, keeps us from getting sick by methods of modern sanitation and largescale immunization. Are we not more, rather than less, human with all this? Furthermore, it is certain that if the technological base of present-day societies were suddenly removed or even seriously disrupted, the result would be chaos and suffering of staggering proportions.

I also wish to make it clear that while in my opinion man-made science can never completely remove the basic mystery of nature, it is nevertheless the best approach we now have for explaining and predicting the behavior of all living and inert matter. Even if we are not capable of grasping the "absolute truth," the evidence is by now overwhelming that science can at least provide us with an image of the truth. As a specific example, the theories concerning the processes which have kept the sun hot for billions of years must have a close correspondence with reality since they have enabled us to imitate those processes in hydrogen bombs. (Whether these bombs should have been built at all is an entirely different question.) I am firmly convinced that no amount of sun-gazing, quiet meditation, or loud prayer would have provided us with a better understanding of the workings of the sun.

If all of mankind is not to slide backward into poverty, disease, strife, ignorance, and superstition, humanity must learn to live with science and technology to adapt to ever changing conditions caused by resource depletion, climatic changes, and population growth. It is obvious but perhaps worth repeating that literature will not keep us physically warm as the fossil fuels get used up in the coming decades. It would be equally unrealistic to expect beautiful paintings and inspiring music to cure leukemia. In matters such as these, our only hope - if there is any - lies in the scientific community.

Although literature does not provide us with new knowledge of the type that would directly shape the future course of humanity, it can do so indirectly by a continuous, sensitive, penetrating, and forceful assessment of the human condition, and by imaginative projections of possible future paths for humanity. In addition to serving humanity as a mirror of its conscience and as a guide for its future, literature should continue to be valued for expanding our consciousness, developing and enriching our imagination, and vicariously broadening our contacts with the outer and the inner worlds of our fellow human beings. Also, as one of the arts, literature will be cherished by many for providing their lives with that feeling of beauty which an agnostic accepts as a substitute for religious sentiments.

In a lecture at Dartmouth College more than 50 years ago, Edwin Slosson, then the director of Science Service, stated that "the question on which the future depends is whether men can muster up among them enough mentality and morality to manage the stupendous powers which applied science has recently placed in their hands." With the experiences of World War I still clearly in his mind, he expressed the pessimistic opinion that "man is mounted on a bigger horse than he can ride."

I personally witnessed World War II at very close range, and I find it hard to be less anxious than Slosson was 50 years ago. The genie of the atomic bomb is out of the bottle - out of the research and development laboratory - and the chances of getting it back in are close to zero. There are some hopeful signs, however. As was demonstrated by the discontinuance of the supersonic transport program which had gathered considerable interest-group support, there is no invincible "technological imperative" as has been suggested. As Dorothy Griffiths, a social scientist, recently stated, "Technology does not thunder forward under the impetus of a mysterious inner momentum" - it can be controlled, but this must apparently be done in the open as part of the political process with broad public participation. Another hopeful sign is that more than 30 years have passed without a third world war.

With all of the above in mind, I cast my personal vote for proceeding with science and technology, although I do so somewhat hesitatingly. It is possible that the aggressive, greedy, and fanatic traits of the human race will eventually lead to a large-scale, catastrophic misuse of science and technology - but at least humanity will have had an active and exciting existence while it lasted!

A professor of engineering sciences,Thomas Laaspere teaches courses in electricalengineering. His interests in theeffects of scientific thought andtechnological development led him toorganize a course in comparative literatureon "Science and Technology as Reflectedin Literature," which he teaches jointlywith a faculty colleague from thehumanities. A native of Estonia, ProfessorLaaspere came to this country as a displacedperson, joining the Dartmouthfaculty in 1961.

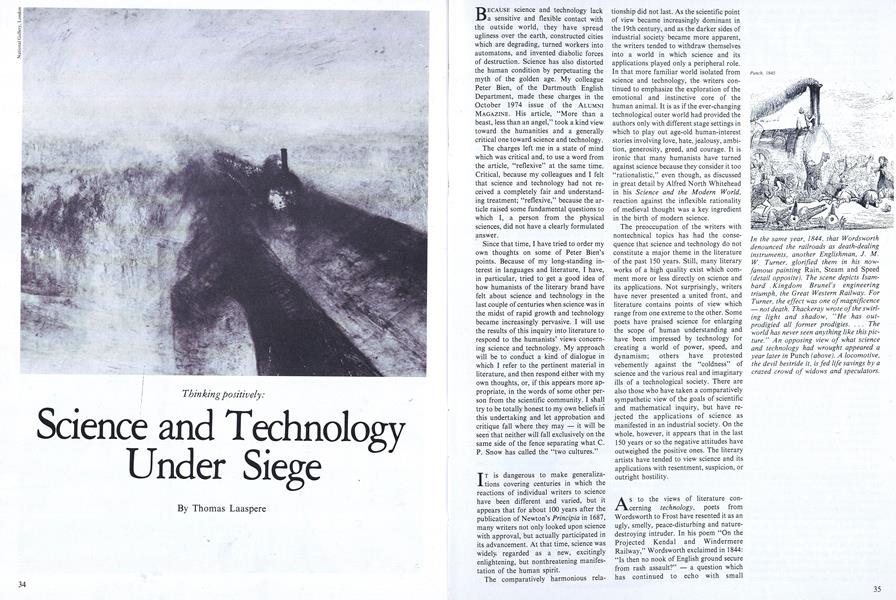

In the same year, 1844, that Wordsworthdenounced the railroads as death-dealinginstruments, another Englishman, J. M.W. Turner, glorified them in his now-famous painting Rain, Steam and Speed (detail opposite). The scene depicts IsambardKingdom Brunei's engineeringtriumph, the Great Western Railway. ForTurner, the effect was one of magnificence- not death. Thackeray wrote of the swirlinglight and shadow, "He has out-prodigied all former prodigies.... Theworld has never seen anything like this picture."An opposing view of what scienceand technology had wrought appeared ayear later in Punch (above). A locomotive,the devil bestride it, is fed life savings by acrazed crowd of widows and speculators.

After watching birds in flight, French airpioneer Louis Mouillard (above) prophesiedin 1881 that man would be able to"rise up in the air and direct himself atwill, even against the wind itself." Lessthan a century later Mouillard's vision ofriding the wind had taken on a moreominous meaning, symbolized by theArmy missile site below.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

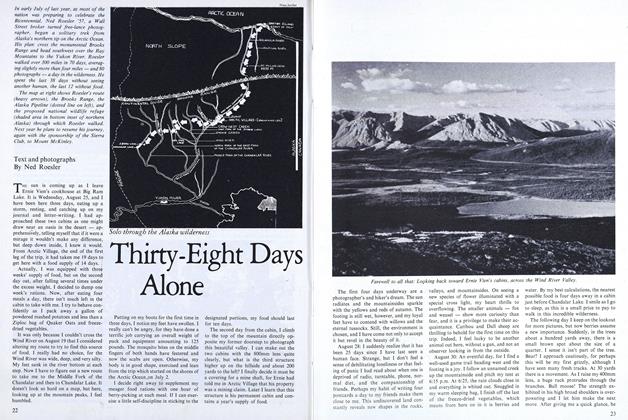

FeatureThirty-Eight Days Alone

September | October 1977 By Ned Roesler -

Feature

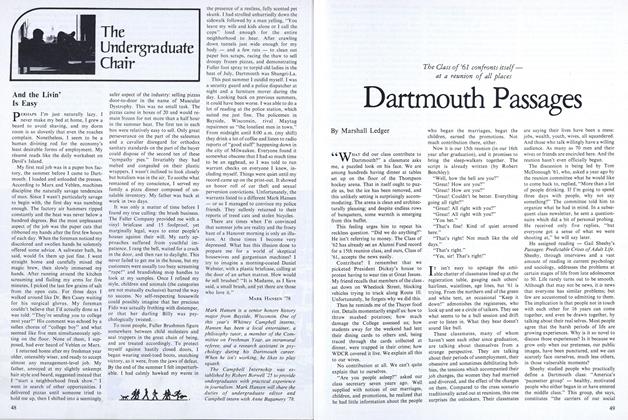

FeatureDartmouth Passages

September | October 1977 By Marshall Ledger -

Feature

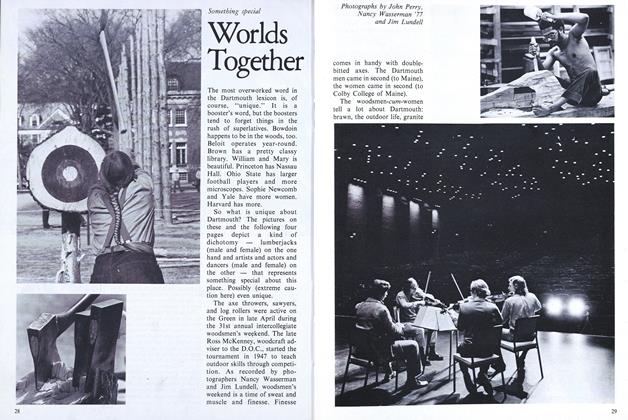

FeatureWorlds Together

September | October 1977 -

Article

ArticleFanciers

September | October 1977 By BRAD HILLS '65 -

Class Notes

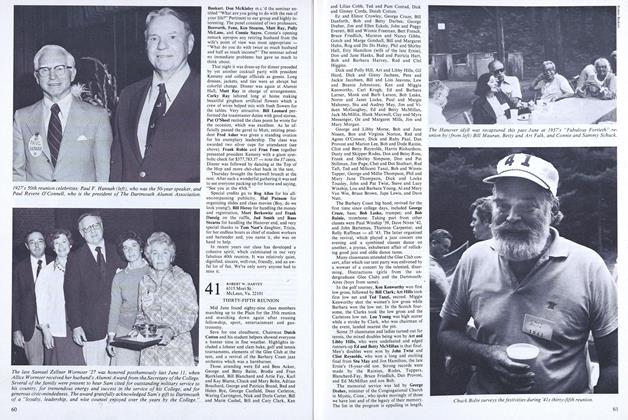

Class Notes1927

September | October 1977 By ERWIN B. PADDOCK -

Class Notes

Class Notes1941

September | October 1977 By ROBERT W. HARVEY, STEVE WINSHIP

Thomas Laaspere

Features

-

Feature

FeatureA Teacher's Real Reward

JUNE 1964 -

Feature

FeatureCarole Berger Professor of English 2 wolves in a single run

January 1975 -

Feature

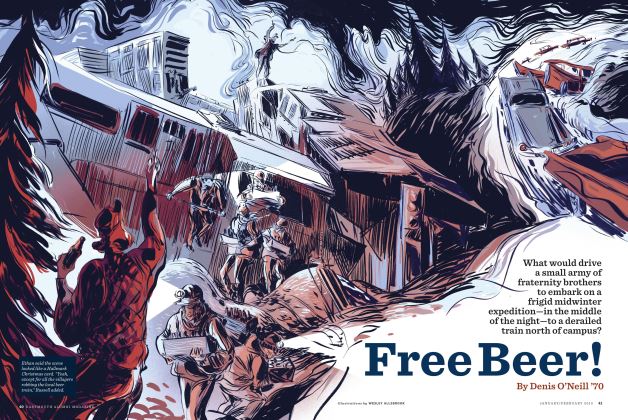

FeatureFree Beer!

JAnuAry | FebruAry By Denis O'Neill ’70 -

Cover Story

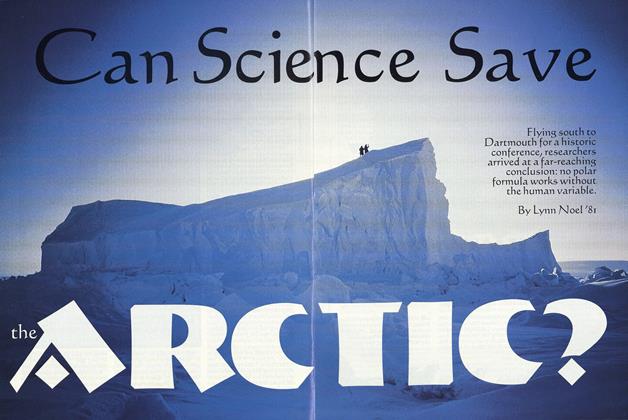

Cover StoryCan Science Save the Arctic?

March 1996 By Lynn Noel '81 -

FEATURES

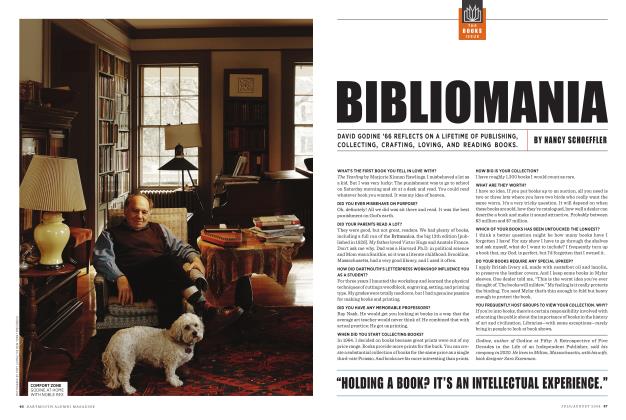

FEATURESBibliomania

JULY | AUGUST 2024 By NANCY SCHOEFFLER -

Feature

FeatureHigh Tech Crisis

JUNE 1983 By Shelby Grantham