NEVER mind the doctors! We should ignore their Hippocratical remarks. They tell us running is the best way not to die (too soon). And hence our parks now teem with converts chasing immortality.

No. Running isn't merely prophylaxis any more than music is an aural tranquilizer, though it also soothes the savage breast. Running is to therapy what Mozart is to Muzak. We do not run to live. We live to run.

Let me expatiate.

Man in a state of nature is a runner. Look at children: They are always running. Their first halting steps are but a transient stage towards culmination in a sprint. We smile to watch them scamper. But if we ever asked ourselves precisely why, we would discover that our smile betrays a deep-felt envy. For a child is free. We grownups must be "civilized." Oh Freud, the most pernicious of our Discontents {das schlechteste Unbehagen, Sig) is that society has arbitrarily set down that adults walk, not run. What tyrant forged this brutal legislation, tearing the Achilles tendon of the Id?

A child who runs along Fifth Avenue is charming. But an adult sprinting in his streetclothes is a lunatic, a lover, or a thief.

The Bible says King David "danced and leaped" before the Ark. I always thought these lines meant that he was joyous. But a recent medical interpretation argues he was doing calisthenics, with longevity in view.

Horace in his Ars Poetica dichotomized the world into the dulce and the utile. And strict dogmatic Roman that he was, he recognized no art in anything that had no usefulness. The modern "classicists" who have inherited this puritan mentality are those prosaic souls who only harp upon the utile of running.

Well, yes. A grain of truth. It is a scientific fact that running is, by chance, salubrious as well. But so is sex. Yet has a man in passion ever cried, "I only do it for my health?" Nay, love transcends the logical. Le coeur a ses raisons. . . .

It has been said that great ideas afflate themselves to people as they run. Perhaps. Once upon a 20 miler, I was struck (or stricken) with the following profundity: Is it mere linguistic hazard that the English word for soul is voiced exactly like the word betokening the bottom of a trackshoe? And is it but coincidence that "sole" is also like the sole in solitary? Surely there is meaning in all this. For when a runner hears the sound of sol, it klangs in him a triad of associations which, religiously appropriate, become a unity. (Run 20 miles and see.)

The distance runner finds his soul in solitude. He is not, pace Alan Sillitoe, a lonely man, for every time one sole alights upon the earth, the other is aloft. He is at one with nature. And he flies. (The winged foot is everywhere in iconology.)

We know that, fellow runners, don't we? When we run, we fly. It is sublimity that few except the mystic poets can express. And it is sensual. Read Roger Bannister (The First Four Minutes). Not the part about his fainting when he breaks the record, but where he describes the ecstasy of running through the woods. He candidly admits there is a touch of eros in it. Who could gainsay Bannister? The man's a doctor, too.

We know that running is both metaphysical and metaphorical. And we recall what Mar veil tells his mistress:

though we cannot make our sunStand still, yet we can make him run.

Or, as the philosopher remarked just after running 20 miles: la course a sesraisons.

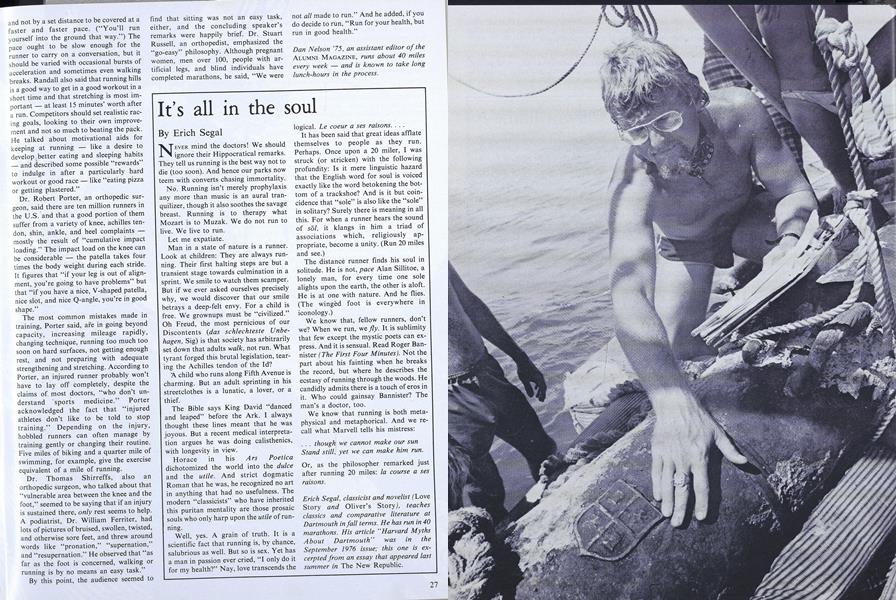

Erich Segal, classicist and novelist (Love Story and Oliver's Story, teachesclassics and comparative literature atDartmouth in fall terms. He has run in 40marathons. His article "Harvard MythsAbout Dartmouth" was in theSeptember 1976 issue; this one is excerpted from an essay that appeared lastsummer in The New Republic.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

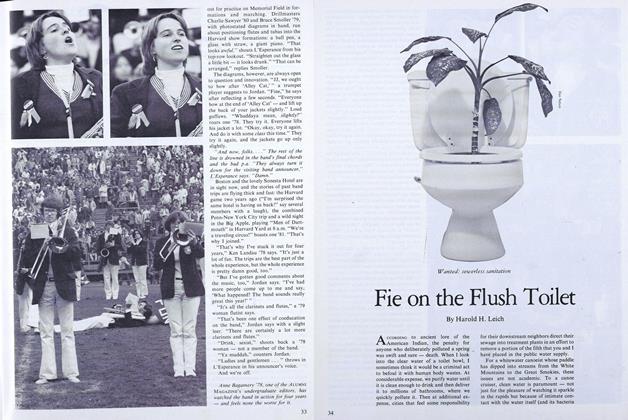

FeatureFie on the Flush Toilet

November | December 1977 By Harold H. Leich -

Feature

FeatureSee How They Run

November | December 1977 By Dan Nelson -

Feature

FeatureThe Campaign for Dartmouth

November | December 1977 -

Article

ArticleThe DCMB Double-entendre March

November | December 1977 By Anne Bagamery -

Article

ArticleDick's House Is Her House

November | December 1977 By S.G. -

Article

ArticleTheir Fathers' Sons

November | December 1977