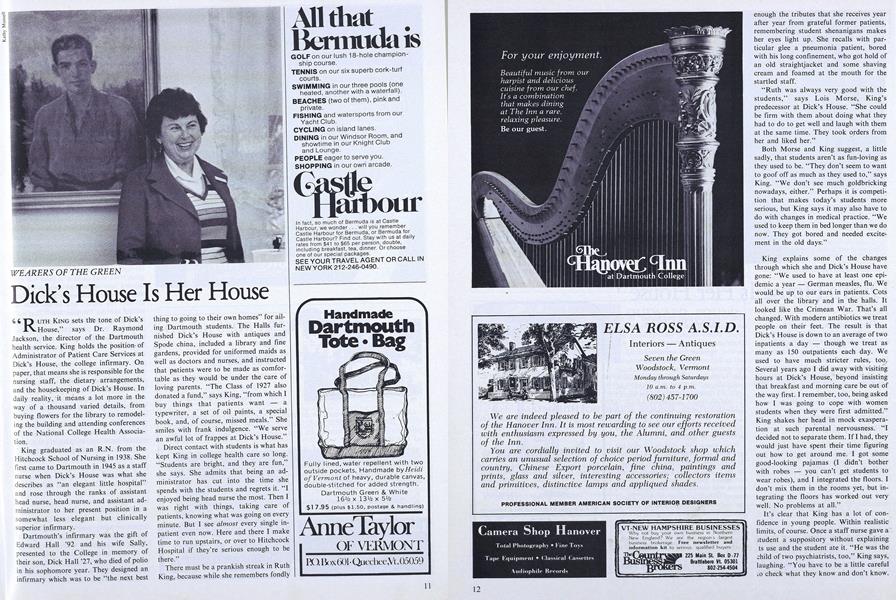

"RUTH KING sets the tone of Dick's House," says Dr. Raymond Jackson, the director of the Dartmouth health service. King holds the position of Administrator of Patient Care Services at Dick's House, the college infirmary. On paper, that means she is responsible for the nursing staff, the dietary arrangements, and the housekeeping of Dick's House. In daily reality, it means a lot more in the way of a thousand varied details, from buying flowers for the library to remodeling the building and attending conferences of the National College Health Association.

King graduated as an R.N. from the Hitchcock School of Nursing in 1938. She first came to Dartmouth in 1945 as a staff nurse when Dick's House was what she describes as "an elegant little hospital and rose through the ranks of assistant head nurse, head nurse, and assistant administrator to her present position in a somewhat less elegant but clinically superior infirmary.

Dartmouth's infirmary was the gift of Edward Hall '92 and his wife Sally, presented to the College in memory of their son, Dick Hall '27, who died of polio in his sophomore year. They designed an infirmary which was to be "the next best thing to going to their own homes" for ailing Dartmouth students. The Halls furnished Dick's House with antiques and Spode china, included a library and fine gardens, provided for uniformed maids as well as doctors and nurses, and instructed that patients were to be made as comfortable as they would be under the care of loving parents. "The Class of 1927 also donated a fund," says King, "from which I buy things that patients want - a typewriter, a set of oil paints, a special book, and, of course, missed meals." She smiles with frank indulgence. "We serve an awful lot of frappes at Dick's House."

Direct contact with students is what has kept King in college health care so long. "Students are bright, and they are fun," she says. She admits that being an administrator has cut into the time she spends with the students and regrets it. "I enjoyed being head nurse the most. Then I was right with things, taking care of patients, knowing what was going on every minute. But I see almost every single inpatient even now. Here and there I make time to run upstairs, or over to Hitchcock Hospital if they're serious enough to be there."

There must be a prankish streak in Ruth King, because while she remembers fondly enough the tributes that she receives year after year from grateful former patients, remembering student shenanigans makes her eyes light up. She recalls with particular glee a pneumonia patient, bored with his long confinement, who got hold of an old straightjacket and some shaving cream and foamed at the mouth for the startled staff.

"Ruth was always very good with the students," says Lois Morse, King's predecessor at Dick's House. "She could be firm with them about doing what they had to do to get well and laugh with them at the same time. They took orders from her and liked her."

Both Morse and King suggest, a little sadly, that students aren't as fun-loving as they used to be. "They don't seem to want to goof off as much as they used to," says King. "We don't see much goldbricking nowadays, either." Perhaps it is competition that makes today's students more serious, but King says it may also have to do with changes in medical practice. "We used to keep them in bed longer than we do now. They got bored and needed excitement in the old days."

King explains some of the changes through which she and Dick's House have gone: "We used to have at least one epidemic a year - German measles, flu. We would be up to our ears in patients. Cots all over the library and in the halls. It looked like the Crimean War. That's all changed. With modern antibiotics we treat people on their feet. The result is that Dick's House is down to an average of two inpatients a day - though we treat as many as 150 outpatients each day. We used to have much stricter rules, too. Several years ago I did away with visiting hours at Dick's House, beyond insisting that breakfast and morning care be out of the way first. I remember, too, being asked how I was going to cope with women students when they were first admitted." King shakes her head in mock exasperation at such parental nervousness. "I decided not to separate them. If I had, they would just have spent their time figuring out how to get around me. I got some good-looking pajamas (I didn't bother with robes - you can't get students to wear robes), and I integrated the floors. I don't mix them in the rooms yet, but integrating the floors has worked out very well. No problems at all."

It's clear that King has a lot of confidence in young people. Within realistic limits, of course. Once a staff nurse gave a student a suppository without explaining ts use and the student ate it. "He was the child of two psychiatrists, too," King says, laughing. "You have to be a little careful to check what they know and don't know. After all, most of them are away from home and on their own for the first time."

The responsibility for educating young people to care for their health is one that King feels deeply. She has been working closely with Doctor Jackson on his recently introduced program of training student health aides, a Dick's House effort which she describes with pride. The dormitories choose their own health aides, who are trained by Dick's House, to which they report with a weekly log. Each aide is provided with a kit - a black briefcase - containing basic home medical supplies (thermometer, bandages, ice bag, throat lozenges, aspirin, and so on) and instruction sheets for self-care of colds, minor injuries, menstrual cramps, and indigestion. Also being reviewed for inclusion in the kits are two cassette films about breast and pelvic examination procedures.

"They do a really fine job," says King about her aides. "Just last year two difficult cases, one a student too drunk for her own safety and another a student who had had a severe fall on the head, were handled beautifully. Both aides knew immediately that they ought to call the campus police get the students over to us for professional care."

The drastic switch from long-term inhouse care to outpatient service has occasioned many changes in Dick's House during King's tenure. Some of them are clearly a disappointment to her, for she takes seriously her duty to the wishes of Dick Hall's parents. On a tour of the infirmary, she points out a recently bricked-up fireplace. A wall now runs into the fireplace at right angles, making two small examining rooms out of what was originally a large, airy lounge. "It's a shame to lose the fireplace," King explains. "But we must meet the needs of the students." '

Other lapses from the elegant standards set by the Halls are the result of increases in the costs of things, especially things medical. And building alterations required to meet the fire safety specifications for accredited hospitals were a major expense. Such alterations also required the replacement of a great deal of lovely wooden molding with plain steel framing.

However, a special fund created by Sally Hall's will keeps the fine upholstery and the lovely wallpaper in good repair. King is glad that this fund exists. It would be impossible, she says, to keep up the crewelembroidered wing chairs and the murals in the hall out of the infirmary budget.

In King's office is preserved the 1927 Dick's House log, which testifies to the persistence among students of the tummy ache and the runny nose. The terminology for them has changed, however: "Grippe" and "catarrh" figure largely in the complaint column of the 1927 log (along with an occasional "drunk"), whereas today's sign-in sheets say "stomach ache" and "cold" (along with an occasional "drunk"). King once made a collection of interesting responses to the question "What is wrong?" on the sign-in sheets used at Dick's House. It includes such gems as "Squirrel bite - we brt. the sq." and "Larangiditis - my voice doesn't go."

Asked what she does by way of recreation, King replies that she belongs to the Grenfell Society, referring to the group of medical practitioners who carry on the pioneering work of Sir Wilfred Grenfell, English medical missionary to the isolated fishing villages of Labrador. Before year-round operation, King spent her summers there as a volunteer nurse, in the small hospital in St. Anthony and at the primitive outport station cabin on Spotted Island. There she ministered to the fishing folk who sent for her, pulling teeth, dressing infected fishhook wounds, and delivering an occasional baby, by kerosene lamp and with water drawn from a brook. Her services were paid for in wood and fish. Although she hasn't had a summer to devote to Labrador in several years now, King still contributes to the work of the society as a member of its board of directors.

Finding out about Ruth King's life off duty is difficult. She will say that she married just last year, and that a St. Bernard came with the husband, and she mentions in an aside that she hopes a professional meeting won't last too long I for her to get back for the Brown game; but most of her conversation is about her work. And if those early nursing days of 12-hour shifts and six-day weeks are added to the volunteer work in Labrador, the tenhour days she puts in now, and the being on call every night as well, the result is a very dedicated nurse.

About her dedication to nursing, King is frustratingly self-deprecating. "Don't print anything about my working ten hours a day," she says. "It will sound as though I'm complaining. And I'm not. It's my own doing." She retreated hastily from owning to anything which sounded as "corny" as "dedication."

But you can't leave Ruth King's pleasant office, or go on a tour of Dick's House with her, or talk with those who have worked with her, without sensing her dedication - in the humane authority with which she discharges her manifold duties and the witty realism with which she happily shoulders the burden of watching over, caring for, putting up with, and teaching the young men and women of Dartmouth.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

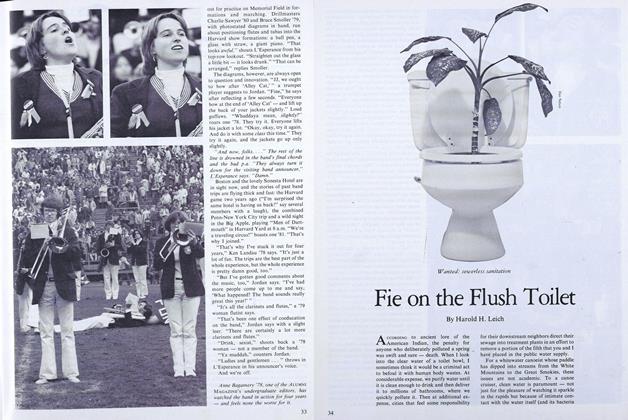

FeatureFie on the Flush Toilet

November | December 1977 By Harold H. Leich -

Feature

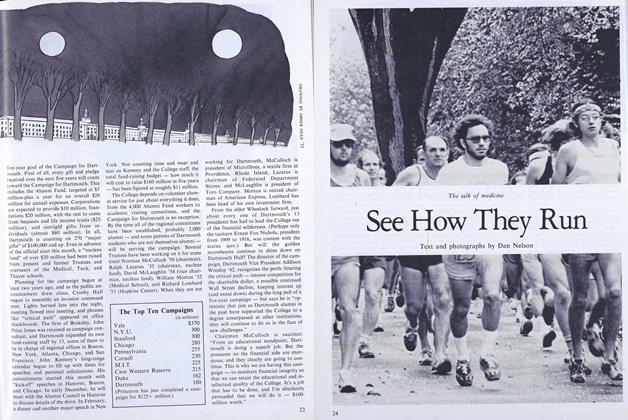

FeatureSee How They Run

November | December 1977 By Dan Nelson -

Feature

FeatureThe Campaign for Dartmouth

November | December 1977 -

Article

ArticleThe DCMB Double-entendre March

November | December 1977 By Anne Bagamery -

Article

ArticleTheir Fathers' Sons

November | December 1977 -

Class Notes

Class Notes1974

November | December 1977 By STEPHEN D. SEVERSON

S.G.

-

Article

ArticleA Versatile, Admirable Teacher With "Every Feature of a Drill Sergeant'(sic)

March 1977 By S.G. -

Article

ArticleA Red Letter Day

April 1977 By S.G. -

Article

ArticleThe Call Heard Round the World

OCT. 1977 By S.G. -

Article

ArticleResident Rotiferologist

DEC. 1977 By S.G. -

Article

ArticleOf God, Man, and Mountains

JAN./FEB. 1978 By S.G. -

Feature

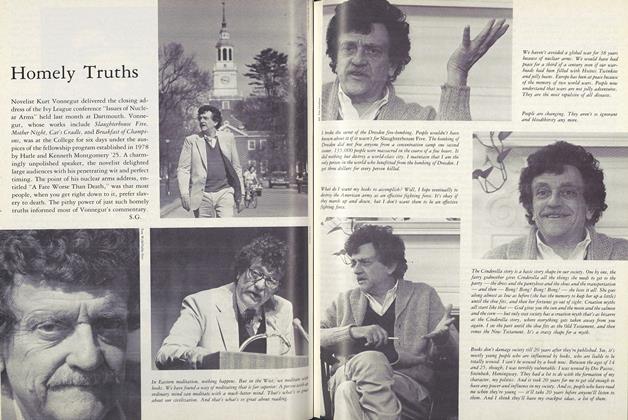

FeatureHomely Truths

JUNE 1983 By S.G.