Twenty years ago most texts and courses in American history paid little attention to Negro slavery and tended to dismiss abolitionists as irresponsible fanatics. During the past decade or so literally hundreds of studies have reexamined every facet of slavery and antislavery, and in so doing have transformed the entire fabric of American history. Indeed, given the prodigious outpouring of fresh and exciting historical discovery, it is difficult to tell students or interested laymen where to begin. Fortunately, James Brewer Stewart has now produced an admirable synthesis of the best work on antislavery, a synthesis that is clear, readable, and remarkably balanced in selectivity and moral judgment.

Professor Stewart has an enviable ability to condense without sacrificing either salient detail or a sense of the larger picture - in this case, the world picture within which America's struggles over slavery took place. Unlike many previous surveys of the subject, Holy Warriors begins by placing the slavery issue within a framework of world history and by providing informative accounts of the origins of American slavery and racial prejudice, of the emergence of antislavery sentiment in the colonial era, and of the reasons that the Founding Fathers could not get rid of an institution that seemed to mock their ideals and aspirations. Stewart is frankly sympathetic to the abolitionists and endorses, with important qualifications, the view expressed by-Wendell Phillips, at the climax of the Civil War, that abolitionism would be a long fight, "only one part of a great fight going on the world over, and which began ages ago,... between free institutions and caste institutions, Freedom and Democracy against institutions of privilege and class."

But this is essentially a history of American abolitionism in its religious and political phases, not a history of slavery in American life. Although Stewart devotes commendable attention to racism, to the critical role that free blacks played in the antislavery movement and as soldiers in the Civil War, and to the complex antipathies and alliances between black and white reformers, he tends to ignore the great majority of Northern whites who even in the 1850s regarded abolitionists with hostility or indifference. This chilling response was not only the result of racism, as Stewart implies, but of complex divergences on many issues including Anglophilia and Anglophobia, an issue that Stewart curiously neglects. I suspect, however, that attitudes toward Britain divided Americans in the 1830s and 1840s even more profoundly than did attitudes toward the Soviet Union in the 1930s and 19405.

On the positive side, Professor Stewart goes well beyond a popular summary of the most recent scholarly literature. He makes new and intriguing points about the family background of abolitionists, a background of internalized principles, respect for parents, and "rebellion" governed by high moral expectations that stands in striking contrast to the patterns described in Christopher Lasch's forthcoming study of the modern family, Haven in a Heartless World. Stewart also raises interesting questions about the geographic regions in which abolitionism flourished, and thus sheds new light on the connections between reformist ideology and the stages of economic growth. Having already written a fine study of Joshua R. Giddings, an early abolitionist Congressman from Ohio, Stewart is at his best in clarifying the complexities of antislavery politics and the processes which transformed a religious movement of "moral suasion" into a potent political force. He also gives a succinct, yet detailed account of the growing militancy of free blacks in the North and of the dramatic struggle against legal segregation, which in 1855 finally triumphed in Massachusetts (many readers will be surprised to learn that in 1850 Charles Sumner and Robert Morris argued before the Massachusetts Supreme Court, without success, "most of the grounds which were to be adopted by the plaintiffs one hundred four years later in the 1954 Brown v. Board of Education of Topeka desegregation suit," and that subsequent sit-ins and boycotts soon led to the first state laws against distinctions of color and religion in the schools).

In short, Holy Worriers can be recommended as an excellent introduction to a subject that has commanded center stage in the continuing reconstruction and re-evaluation of our past.

HOLY WARRIORS:THE ABOLITIONISTS ANDAMERICAN SLAVERYBy James Brewer Stewart '62Hill and Wang, 1976. 226 pp. $10

David Brion Davis is Farnam Professor ofHistory at Yale. He has written several bookson slavery and antislavery. At last June'sCommencement he received an honoraryLitt. D. from Dartmouth.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

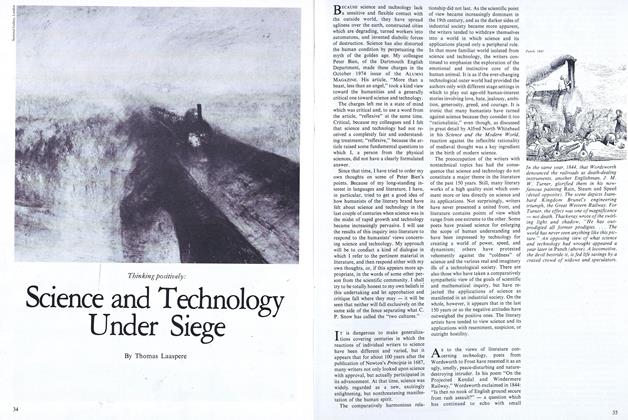

FeatureScience and Technology Under Siege

September | October 1977 By Thomas Laaspere -

Feature

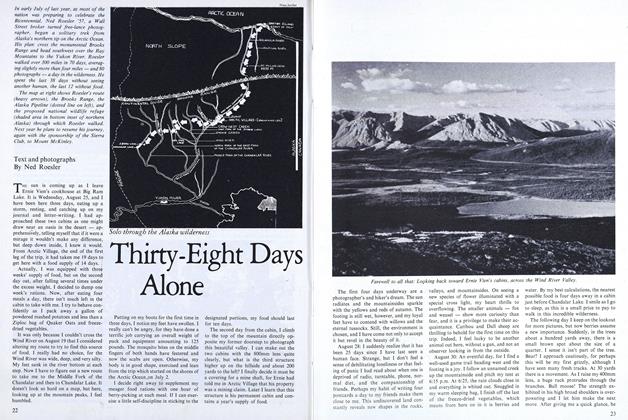

FeatureThirty-Eight Days Alone

September | October 1977 By Ned Roesler -

Feature

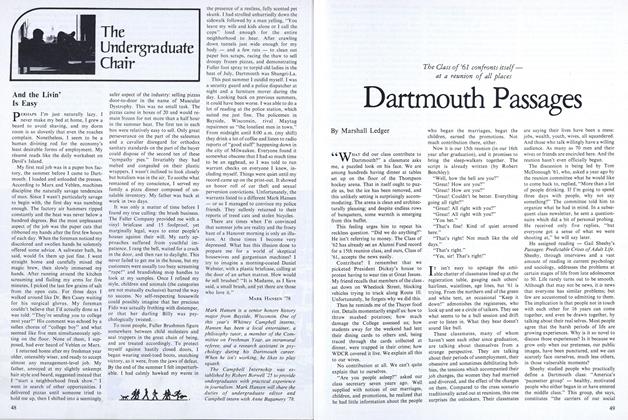

FeatureDartmouth Passages

September | October 1977 By Marshall Ledger -

Feature

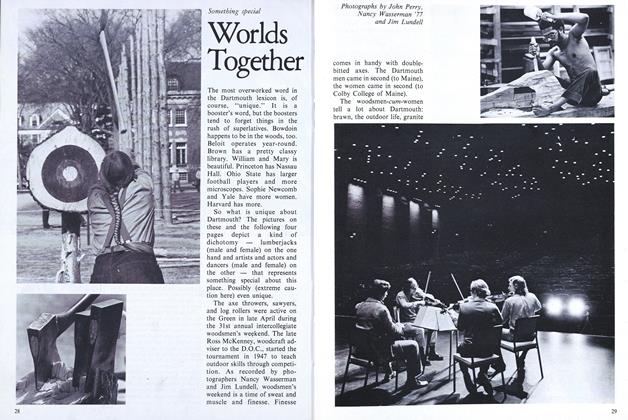

FeatureWorlds Together

September | October 1977 -

Article

ArticleFanciers

September | October 1977 By BRAD HILLS '65 -

Class Notes

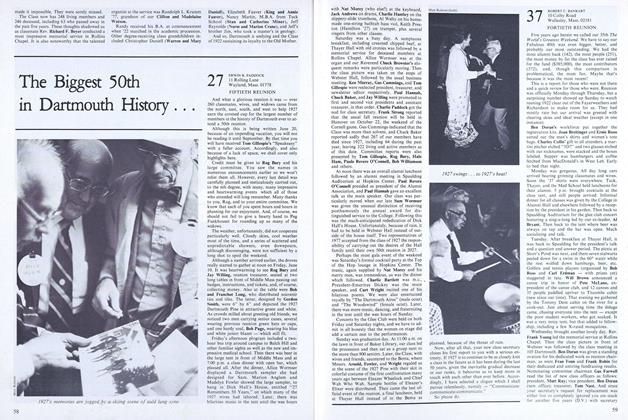

Class Notes1927

September | October 1977 By ERWIN B. PADDOCK

DAVID BRION DAVIS '50

Books

-

Books

BooksALUMNI PUBLICATIONS

March, 1923 -

Books

BooksA SYNOPTIC HISTORY OF THE GRANITE STATE,

February 1940 By Herbert W. Hill -

Books

BooksExperiential Education

OCTOBER 1981 By Michael Colacchio '80 -

Books

BooksTHE INCHWORM WAR AND THE BUTTERFLY PEACE.

JANUARY 1971 By SYLVIA MORSE MCKEAN -

Books

BooksTHE COLLECTED POEMS OF DILYS LAING.

JANUARY 1968 By VERA VANCE -

Books

BooksHUMAN EMBRYOLOGY

October 1946 By W. W. Ballard '28