THE checkered history of crew at Dartmouth is a story of snow, fire, world wars, and logging operations interfering with the unheralded hard work of a band of college rowers. Crew began in 1856 but was effectively killed two years later when a nocturnal flood carried away the boats, which were stored on a raft moored to the Connecticut River bank. They were never seen again.

Crew was revived after a mass meeting of the student body in the late fall of 1872, and Dartmouth competed, without too much success, in regattas at Saratoga, New York. On one trip to Saratoga, the rowers' practice shell, which was strapped to the top of a railroad car, caught fire from the sparks of the engine. The collapse of the boathouse under heavy snow during the winter of 1877 and the destruction of the rowing association's shells and paraphernalia caused the abandonment of rowing.

There were occasional efforts to revive the sport, but none was successful until 1933 when a rowing club was established. The crew was forced to row on nearby Lake Mascoma in Enfield because loggers were using the Connecticut to get their lumber to market. Crew continued to be a fairly low key operation and then during World War II stopped once more. The rowers started up again after the war, locating their boathouse on the Connecticut River.

"The best thing that happened was when the boathouse collapsed under heavy snow in 1952," says Peter Gardner, who is now in his 21st season as head coach of the Dartmouth crew. "They got considerable publicity and the crews got better after that." The rebuilt facility was named Fuller Boathouse, after Alvan T. Fuller, the former Massachusetts governor who contributed reconstruction funds.

Dartmouth's heavyweight crews dominated the Class II division in which they competed during the late 1950s under the coaching of Thaddeus Seymour, an English professor who later became Dartmouth's dean and, successively, president of Wabash College and Rollins College. Gardner was hired in 1958 when Dartmouth ambitiously decided to go big time in crew.

On May 6, the 1978 edition of the Dartmouth heavyweight crew captured the Cochrane Cup in a regatta at Hanover, defeating Wisconsin and M.I.T. in the annual triangular meeting of the three schools. It was the fourth time, and first time since 1970, that Dartmouth won the cup, which honors Admiral Edward L. Cochrane, a former vice president of M.I.T. who was a director of the Navy's Bureau of Ships during World War 11. Wisconsin has won the race ten times and M.I.T. four times in the 18 years of competition.

The Green crew covered the 2,000-meter race in 6:03.6 and moved to a length lead as the shells crossed the finish line. "The victory was a satisfying one," says the laconic Gardner, a 1949 Princeton graduate who is the dean of the nation's collegiate rowing coaches and, for the second year in a row, is serving as head coach of the U.S. National Rowing Team. "Wisconsin has been quite a powerhouse in recent years, so the successes have been few and far between. I'm glad to get back on the winning track. Some success helps any program because it spurs you on."

A week after the Cochran Cup victory, the freshman lightweights provided a nice surprise by winning the Eastern Sprints championship. They beat Navy and pre-race favorite Harvard in what was only the second time ever that a Dartmouth crew won a Sprints championship. Meanwhile, the varsity heavyweights finished ninth overall.

Capturing the Cochrane Cup or the lightweight Sprints doesn't necessarily make a successful season, however. "What we really shoot for are the national championships," Gardner explains. "Even to make the finals - the top six crews - is a real accomplishment."

At Dartmouth, crew is a club composed of about 100 men and women. The Dartmouth College Athletic Council pays the basic expenses of running the rowing program with the Friends of Dartmouth Rowing and the members' dues paying other expenses. There are three squads: the heavyweights, the lightweights (the average weight of the rowers can't exceed 155 pounds) and the women. These squads are further broken down into varsity, second varsity, and freshmen. Women rowers have a novice category open to upperclassmen who have not rowed before and freshmen.

A lot of students try out for crew during the fall term when some of the upperclassmen rowers are not on campus. A lot of those who try out don't stick with it. "This is not a sport you'd get into for glory," observes Gardner. "It takes a lot of hard work, and the exposure to the press and campus recognition is much less than it would be in other sports. Crew is very similar to cross-country skiing and crosscountry running. In fact, one of my best oarsmen, Dan Billman, is a good crosscountry skier and is on the ski team. Heavyweight crew captain Rob Wilkes is a top squash player at Dartmouth."

The outstanding oarsman on the varsity heavyweight squad, whose members average six feet four inches and 190 pounds, is Kurt Somerville, a junior. Last summer he made the Gardner-coached U.S. National Rowing Team that finished sixth at the world championships in Amsterdam. "He's in an elite class," says Gardner of Somerville. "We haven't had many at Dartmouth in international competition. It's like being an all-American."

Rowers go through a rugged physical training period. Fall is devoted to rowing and some running with the goals of developing more efficient technique and a conditioning base. Part of the running includes racing as many as 20 times (with 50 second "rest" intervals) to the top of the football stands. During the winter, team members ski cross-country three to four times a week for 60 to 90 minutes. The other three days of the week are set aside for weight-lifting and rowing practice in the simulator tanks in the basement of Alumni Gymnasium. "On Saturday morn- ings we hold a cross-country ski race and Sunday is our day off, although some people ski on Sunday," notes Gardner. Toward the end of the winter the rowers switch to circuit training, which is designed to improve muscular endurance.

The crew spends ten days of spring vacation in Tampa, Florida. "The people get down any way they can," says Gardner. "They pay their own way and I drive the truck. Once we're there, the College picks up the room and board." The team rows in Tampa Bay most of the time in double sessions. "We get up at 5 and row in the morning and at 3 in the afternoon. They sleep in between." The training period culminates with a race against other schools.

When the crew members return to Hanover they have to hope the ice is out of the Connecticut River. They were unlucky this year and couldn't get onto the water until April 14. "That's the latest since I've been here," says Gardner. "It's a disadvantage for us in races early in the season, but by the end of May we're usually able to overcome that. The water's been pretty good this spring; we haven't had any problems with the currents. The water is still cold and that's a constant threat if anyone falls in or a boat sinks."

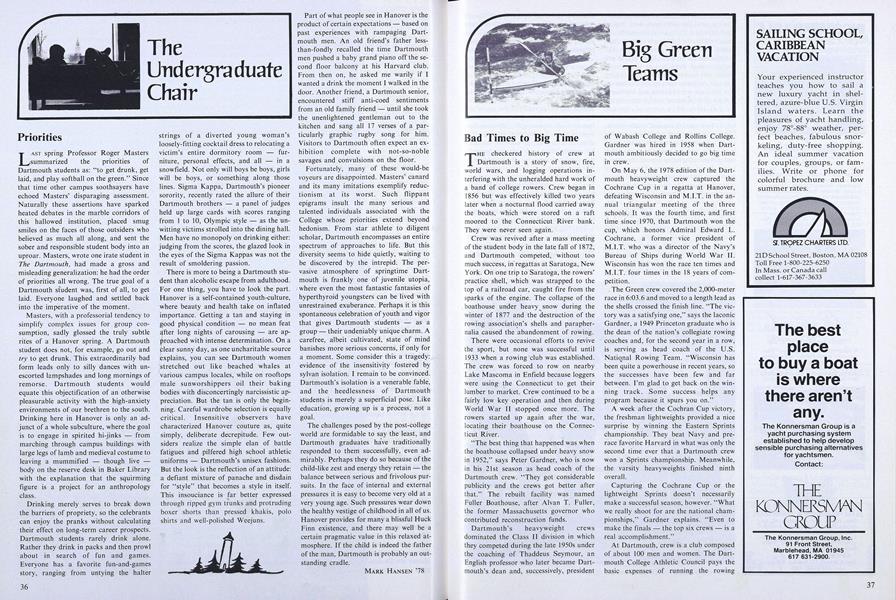

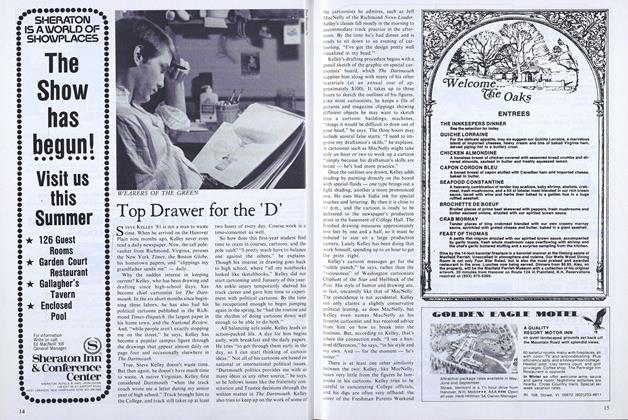

The Dartmouth crew, with poles instead of oars, struck a manly pose in the 1870s.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureShhh. There still are idealists abroad and they're called the Peace Corps

June 1978 By Dan Nelson -

Feature

FeatureHonorary Degrees

June 1978 -

Feature

FeatureThe Valedictories

June 1978 -

Feature

FeatureFancies, Toyes and Dreames

June 1978 By Mark Hansen -

Class Notes

Class Notes1974

June 1978 By STEPHEN D. SEVERSON -

Article

ArticleTop Drawer for the 'D'

June 1978 By A.E.B