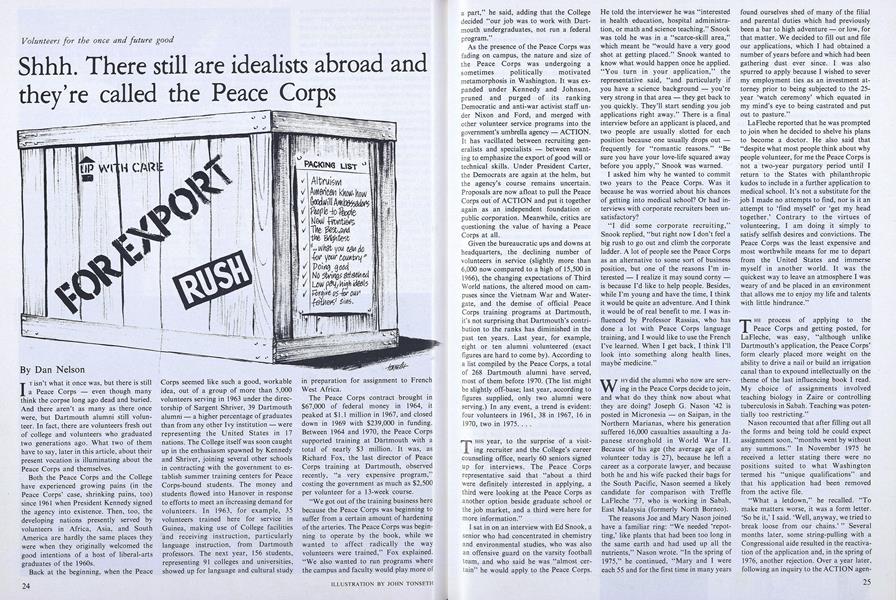

Shhh. There still are idealists abroad and they're called the Peace Corps

JUNE 1978 Dan NelsonVolunteers for the once and future good

IT isn't what it once was, but there is still a Peace Corps - even though many think the corpse long ago dead and buried. And there aren't as many as there once were, but Dartmouth alumni still volunteer. In fact, there are volunteers fresh out of college and volunteers who graduated two generations ago. What two of them have to say, later in this article, about their present vocation is illuminating about the Peace Corps and themselves.

Both the Peace Corps and the College have experienced growing pains (in the Peace Corps' case, shrinking pains, too) since 1961 when President Kennedy signed the agency into existence. Then, too, the developing nations presently served by volunteers in Africa, Asia, and South America are hardly the same places they were when they originally welcomed the good intentions of a host of liberal-arts graduates of the 1960s.

Back at the beginning, when the Peace Corps seemed like such a good, workable idea, out of a group of more than 5,000 volunteers serving in 1963 under the directorship of Sargent Shriver, 39 Dartmouth alumni - a higher percentage of graduates than from any other Ivy institution - were representing the United States in 17 nations. The College itself was soon caught up in the enthusiasm spawned by Kennedy and Shriver, joining several other schools in contracting with the government to establish summer training centers for Peace Corps-bound students. The money and students flowed into Hanover in response to efforts to meet an increasing demand for volunteers. In 1963, for example, 35 volunteers trained here for service in Guinea, making use of College facilities and receiving instruction, particularly language instruction, from Dartmouth professors. The next year, 156 students, representing 91 colleges and universities, showed up for language and cultural study in preparation for assignment to French West Africa.

The Peace Corps contract brought in $67,000 of federal money in 1964, it peaked at $1.1 million in 1967, and closed down in 1969 with $239,000 in funding. Between 1964 and 1970, the Peace Corps supported training at Dartmouth with a total of nearly $3 million. It was, as Richard Fox, the last director of Peace Corps training at Dartmouth, observed recently, "a very expensive program," costing the government as much as $2,500 per volunteer for a 13-week course.

"We got out of the training business here because the Peace Corps was beginning to suffer from a certain amount of hardening of the arteries. The Peace Corps was beginning to operate by the book, while we wanted to affect radically the way volunteers were trained," Fox explained. "We also wanted to run programs where the campus and faculty would play more of a part," he said, adding that the College decided "our job was to work with Dartmouth undergraduates, not run a federal program."

As the presence of the Peace Corps was fading on campus, the nature and size of the Peace Corps was undergoing a sometimes politically motivated metamorphosis in Washington. It was expanded under Kennedy and Johnson, pruned and purged of its ranking Democratic and anti-war activist staff under Nixon and Ford, and merged with other volunteer service programs into the government's umbrella agency - ACTION. It has vacillated between recruiting generalists and specialists - between wanting to emphasize the export of good will or technical skills. Under President Carter, the Democrats are again at the helm, but the agency's course remains uncertain. Proposals are now afloat to pull the Peace Corps out of ACTION and put it together again as an independent foundation or public corporation. Meanwhile, critics are questioning the value of having a Peace Corps at all.

Given the bureaucratic ups and downs at headquarters, the declining number of volunteers in service (slightly more than 6,000 now compared to a high of 15,500 in 1966), the changing expectations of Third World nations, the altered mood on campuses since the Vietnam War and Water-gate, and the demise of official Peace Corps training programs at Dartmouth, it's not surprising that Dartmouth's contribution to the ranks has diminished in the past ten years. Last year, for example, eight or ten alumni volunteered (exact figures are hard to come by). According to a list compiled by the Peace Corps, a total of 268 Dartmouth alumni have served, most of them before 1970. (The list might be slightly off-base; last year, according to figures supplied, only two alumni were serving.) In any event, a trend is evident: four volunteers in 1961, 38 in 1967, 16 in 1970, two in 1975

THIS year, to the surprise of a visiting recruiter and the College's career counseling office, nearly 60 seniors signed up for interviews. The Peace Corps representative said that "about a third were definitely interested in applying, a third were looking at the Peace Corps as another option beside graduate school or the job market, and a third were here for more information."

I sat in on an interview with Ed Snook, a senior who had concentrated in chemistry and environmental studies, who was also an offensive guard on the varsity football team, and who said he was "almost certain" he would apply to the Peace Corps. He told the interviewer he was "interested in health education, hospital administration, or math and science teaching." Snook was told he was in a "scarce-skill area," which meant he "would have a very good shot at getting placed." Snook wanted to know what would happen once he applied. "You turn in your application," the representative said, "and particularly if you have a science background - you're very strong in that area - they get back to you quickly. They'll start sending you job applications right away." There is a final interview before an applicant is placed, and two people are usually slotted for each position because one usually drops out frequently for "romantic reasons." "Be sure you have your love-life squared away before you apply," Snook was warned.

I asked him why he wanted to commit two years to the Peace Corps. Was it because he was worried about his chances of getting into medical school? Or had interviews with corporate recruiters been unsatisfactory?

"I did some corporate recruiting," Snook replied, "but right now I don't feel a big rush to go out and climb the corporate ladder. A lot of people see the Peace Corps as an alternative to some sort of business position, but one of the reasons I'm interested I realize it may sound corny is because I'd like to help people. Besides, while I'm young and have the time, I think it would be quite an adventure. And I think it would be of real benefit to me. I was influenced by Professor Rassias, who has done a lot with Peace Corps language training, and I would like to use the French I've learned. When I get back, I think I'll look into something along health lines, maybe' medicine."

WHYdid the alumni who now are serving in the Peace Corps decide to join, and what do they think now about what they are doing? Joseph G. Nason '42 is posted in Micronesia - on Saipan, in the Northern Marianas, where his generation suffered 16,000 casualties assaulting a Japanese stronghold in World War 11. Because of his age (the average age of a volunteer today is 27), because he left a career as a corporate lawyer, and because both he and his wife packed their bags for the South Pacific, Nason seemed a likely candidate for comparison with Treffle LaFleche '77, who is working in Sabah, East Malaysia (formerly North Borneo).

The reasons Joe and Mary Nason joined have a familiar ring: "We needed 'repotting,' like plants that had been too long in the same earth and had used up all the nutrients," Nason wrote. "In the spring of 1975," he continued, "Mary and I were each 55 and for the first time in many years found ourselves shed of many of the filial and parental duties which had previously been a bar to high adventure - or low, for that matter. We decided to fill out and file our applications, which I had obtained a number of years before and which had been gathering dust ever since. I was also spurred to apply because I wished to sever my employment ties as an investment attorney prior to being subjected to the 25year 'watch ceremony' which equated in my mind's eye to being castrated and put out to pasture."

LaFleche reported that he was prompted to join when he decided to shelve his plans to become a doctor. He also said that "despite what most people think about why people volunteer, for me the Peace Corps is not a two-year purgatory period until I return to the States with philanthropic kudos to include in a further application to medical school. It's not a substitute for the job I made no attempts to find, nor is it an attempt to 'find myself or 'get my head together.' Contrary to the virtues of volunteering, I am doing it simply to satisfy selfish desires and convictions. The Peace Corps was the least expensive and most worthwhile means for me to depart from the United States and immerse myself in another world. It was the quickest way to leave an atmosphere I was weary of and be placed in an environment that allows me to enjoy my life and talents with little hindrance."

THE process of applying to the Peace Corps and getting posted, for LaFleche, was easy, "although unlike Dartmouth's application, the Peace Corps' form clearly placed more weight on the ability to drive a nail or build an irrigation canal than to expound intellectually on the theme of the last influencing book I read. My choice of assignments involved teaching biology in Zaire or controlling tuberculosis in Sabah. Teaching was potentially too restricting."

Nason recounted that after filling out all the forms and being told he could expect assignment soon, "months went by without any summons." In November 1975 he received a letter stating there were no positions suited to what Washington termed his "unique qualifications" and that his application had been removed from the active file.

"What a letdown," he recalled. "To make matters worse, it was a form letter. 'So be it,' I said. 'Well, anyway, we tried to break loose from our chains.' " Several months later, some string-pulling with a Congressional aide resulted in the reactivation of the application and, in the spring of 1976, another rejection. Over a year later, following an inquiry to the ACTION agency by a Congressman, Nason received a telephone call asking him if he wanted to serve as a lawyer in Micronesia, working as an adviser to a mayor or municipal council on one of the islands. A job where Mary could use her training as a nurse was also mentioned, but not guaranteed.

"I was exhilarated by the prospects, even though it came as such a surprise," Nason noted, "but when I told Mary the news she was not very enthusiastic. After several more phone calls, further medical and dental exams, and additional intra-spouse soul-searching, Mary and I had crossed the Rubicon, or, should I say, the Pacific."

For both LeFleche and the Nasons, leaving home was not terribly traumatic. LaFleche said he wanted to avoid slipping into a life he would eventually look back on with dissatisfaction and that "the decision to leave the U.S. became rather easy, even desirous. I had no need for graduate school or to make business connections, although it was emotionally difficult to lose the constant presence of companions or family. Intellectually, however, I wanted to make a conscious and decisive step in another direction."

Nason simply stated that "I left my job with no regrets or pangs of conscience as to whether it was the right move, only some pity for the men who were stuck there. I have a leave of absence from my position, so I can return to it if I choose."

If the volunteers made their decision easily, their families and friends took it harder. Nason's 80-year-old mother greeted his decision with vehemence: " 'You're going where? You must be crazy! How could I possibly explain your irrational and childish behavior to my friends?' " was her first reaction, Nason said. "And our friends were incredulous," he added. "At the office where I had labored so long and faithfully, I was regarded by my fellow officers as a pariah. I had broken faith with not only 'The American Group' (a rather high-blown name for State Mutual Life and its affiliated companies) but with corporate America, which had turned me off for a long time. Most of our contemporaries think we're nuts, but most young people think our volunteering is great. In fact, during training, one'comment we heard several times was, 'I wish my folks would do something like you're doing.' "

LaFleche's contemporaries, although young, were definitely skeptical. When he told them what he was planning, "some snickered with apparent contempt. (These were fellow graduating seniors who played the game of comparing the annual salaries of their new positions in banks and firms, or the impact of the prestigious name of the grad school to which they had been accepted. Peace Corps was low on the list, maybe not even a contender.) Some replied with an 'Oh, I'm sorry to hear that,' and some simply replied, 'Oh.' Some laughed in disbelief, some were first angered then confused (these were members of my family), and a few smiled and understood. Most curious of all was the reaction of those persons who considered my decision as an escape from something. They tried to reason with me, employing a placating tone of voice."

AFTER an application is accepted and an assignment to a country is made, a volunteer receives cultural and language training designed, according to LaFleche, to satisfy two goals: "Preparation for life in a new culture and to ferret out those persons insecure about their reasons for becoming a volunteer. The training was intense and demanding. Days of tedium and instances of paternalism were never rare, but basically I was pleased to find the training staff as individual and motivated as the trainees."

Before being flown to Micronesia for language training, the Nasons went through three days of "staging" in Los Angeles which consisted, in part, of "advice and counsel on such exotic subjects as what happens when a trainee gets im- pregnated, marries a native, gets bitten by a shark, gets dysentery, needs money, gets robbed, etc."

Language training, for the Nasons, was frustrating, partly because in the Chamorro language "one verb, for exampie, can be transformed into 26 different words by the addition of various suffixes," and mostly because Chamorro "is only spoken by about 150,000 people, most of whom live on Guam where English is rapidly taking its place." In addition, because Chamorro is a spoken language only, without any literature, "grammar and syntax depend more on sound than on rules." Mary Nason pointed out that the six weeks of language classes, which lasted from 7:30 a.m. until noon, six days a week, were "taught by a new method called the 'silent way.' The teacher, a 21-year-old college girl attending the University of Guam, says nothing all morning and we have to learn to pronounce the words and learn what they mean from her pointing to word charts on the board. We are not allowed to take notes, have a book, or look anything up, so we have to learn the language by memory. It is very difficult."

LaFleche said that when he volunteered for Malaysia he was confident he'd made the right choice but was "scared of the unexpected." He explained that'"Sabah is one of the 13 states in the Malaysian federation. Malaya, the pre-independence name, was easy to locate on the map. Sabah didn't seem to exist. Was the Peace Corps pulling my leg? When I discovered that Sabah was once known as North Borneo, images and expectations ran wild within my mind - naked, savage headhunters, primitive life, eating with my hands, dancing and singing to the moon, working in a tiny village 'with the people.' Typical American romanticism? Yes, I had it, too." Nonetheless, LaFleche maintains he went with a clear head, simply hoping "that Sabah would still be there when I arrived. I didn't want the place to make any 'great leap forward' in development before I got there."

LaFleche works in the government program to control tuberculosis in Sabah. "That is what I do, on government forms," he wrote. "To assign a positional title in front of my name, other than volunteer, would be impossible. Actually, the government is reluctant to tell me exactly what I should do, and my local co-workers have no interest in telling me what should be done, which means I am completely free to try most anything in controlling TB, which is still the largest killer in Sabah."

He went on to say that "in my attempts to help Sabah control TB, my interest, energy, and activities are spread like a French pate over the program. I am a technician when examining sputum slides for evidence of tuberculosis germs; I am a nurse when I go to the jungle and give vaccinations; I am a health educator when I make attempts to assuage the traditional fears of school children that vaccination will cause, not help, sickness; I am an administrator when I try to inject some further efficiency and continuity into the structure and function of the program; I am an energetic coach when I try to dispell the "it-doesn't-really-matter" attitude of

the typical government employee in Sabah. In the rural jungle villages I am considered the orang-putih, or white man, who is to be as strong and capable as the Six Million Dollar Man in solving any current problem."

NASON said that although he and his wife went to Micronesia with the "hope of helping and training a less-advantaged native people, we did not have the rosy, optimistic outlook of some of the younger volunteers." Nonetheless, they still experience disappointments and frustrations. "My wife sometimes wonders if her work at Public Health is only allowing her co-workers to take more time off. My work at the legislature is certainly necessary, as they need many more than the five young local Chamorro lawyers here at this difficult time when their new country is being born. What sometimes gives me pause, however, is the realization that if I wasn't working here the government would simply hire another stateside lawyer on a contract basis, and the money they save by my working free, they dissipate in the grossest extravagances and waste."

Nason has been working as an adviser to the legislature during the establishment of a bicameral congress, occasioned by the transition from Trust Territory to commonwealth status, and he has been caught in the tension between the islands' desire for independence and the dependence on U.S. aid and war-claims funds. He has observed a certain amount of anti-American feeling in Saipan, but has not noticed it directed against Peace Corps volunteers "who are regarded to a certain extent as freaks because they work for nothing." Nason predicts that an independent Saipan will come to "hate" Americans and "will condemn us for having destroyed their culture which, in my opinion, is neither very distinctive nor illuminating. No doubt they will spray the buildings and fill the air with 'Yankee Go Home!'" U.S. mismanagement of the Trust Territories after the war, and the way in which aid and war-claims monies have been spent, Nason maintains, is part of the reason why "the local Chamorro and Carolinian peoples are hardly ready for independence and self-government."

Frankly admitting that neither he nor the other volunteers are happy with their jobs, Nason says "the reason for our frustration is that most of us are not using our full potential. This is not the fault of the volunteers, but of the people and agencies with whom we work here. This is not, of course, an uncommon reaction of Peace Corps volunteers; in fact, it is standard. The Chamorro way of doing things is slow, inefficient, corrupt, and dictated by politics and familial considerations. Naturally, it is frustrating to operate in this atmosphere. It is my understanding that this is the rule rather than the exception in other countries. It is certainly a testing experience, particularly for the younger volunteers, in adapting and learning how to roll with the punch. Once one learns to cope with the situation and adopt a fatalistic attitude, he has arrived at the threshold of survival in the Peace Corps."

Despite his dissatisfaction with his assignment, Nason maintains that the overall effect and influence of the Peace Corps on Saipan is beneficial - "not so much as a result of what we do in our jobs, but more because of the face-to-face contact with the natives and the example we set in showing that not all Americans are interested in them in order to exploit them." He says he enjoys working with and being accepted as an equal by the younger volunteers, and that serving with his wife has made for a closer marriage. Other than missing family and friends, both the Nasons say they have no regrets about their decision.

Nason qualified his criticisms by stating that "our experience has to be considered representative of Saipan, the most developed of all the islands of Micronesia. Many volunteers are sent to remote atolls with no modern conveniences whatsoever. We would have been willing to give such a life a try, but didn't have the opportunity." Another volunteer, who had taken two years off from Vassar to serve on one of those remote Micronesian atolls, was asked what he thought of Nason's impression of Saipan - whether or not it was perhaps jaundiced by unfortunate personal experience. "They are legitimate gripes," he said. "Micronesia is probably one of the most frustrating places in the world to be a volunteer, and Saipan is the worst place in Micronesia. It has one of the highest, if not the highest, drop-out rates of all Peace Corps programs."

LAFLECHE wrote from Sabah that his satisfactions "usually come in slivers." His greatest frustration, common, it seems, to most volunteers, is with the almost imperceptible rate of progress, a problem brought to a head by the differences between American expectations and the pace of life in the host country. In Sabah, LaFleche said, there is reluctance to allow even for the possibility of improvement.

"I kept wanting to influence major changes," he added. "I wanted co-workers' attitudes to change within days. This was unrealistic. I had to realize that the situation wouldn't change here even in months. I became aware that my presence in Sabah, and with the TB program, was individual and basically minimal. It followed that my energy and efforts had to be directed to achieve goals that I, as one individual, was capable of achieving. Placing the extent of my influence in its proper perspective has released me from the burden of frustration and disappointment. Today, the personal rewards come frequently, not from the realization of major changes, but from the satisfaction that a progression of minor changes is being achieved."

There has been no mistrust or animosity between the volunteers in Sabah and the people they work with, LaFleche said, although there is some curiosity about motives. "The local people don't really understand the meaning of a volunteer. Their own time and energy are constantly spent on acquiring their own needs. Of course, they believe in helping one another, but the idea of a foreigner coming so far to help confuses them. Why would I desire to leave an environment that in their eyes has everything and come to a place that is far behind? Sometimes they simply laugh." LaFleche wouldn't make any generalization about his hosts, partly because Sabah is comprised of 32 different racial groups, each with its own language, and partly because he felt his impressions and interpretations were still incomplete. But he did say that "although the people exhibit an observable degree of Westernization, it is truly a veneer that barely covers the traditional culture and Asian manner of each racial group."

"The atmosphere is relaxed," he wrote. "The weather is tropically beautiful. Sabah was named 'The Land Below the Wind' by European sailors in the 16th century, as it is below the typhoon belt surrounding the Philippines and Hong Kong. [Nason noted that sailors described the Northern Marianas as 'The Isles of Thieves'] The pace is slow and the people are refreshingly friendly. The environment is culturally exciting and challenging. The food and tropical fruits are priceless. The women are intoxicatingly beautiful. 1 think the living conditions are bearable."

I asked him what he planned on doing when he returned to the States. "Who said anything about my coming home?" he replied.

THE effect of the Peace Corps experience on the volunteers who do come home just might be the best justification for the continued existence of the Peace Corps - quite aside from the help the agency might be giving to developing nations and aside from the potential impact of volunteers as good-will ambassadors. A surprising number of volunteers have returned to positions in all levels of government, with public-service institutions, in foreign affairs, as journalists, and as educators - as makers of policy and molders of opinion.

David Dawley '63, who served in Honduras and is now on the Peace Corps' National Advisory Board, cited as examples a few of his acquaintances from Dartmouth: Tim Kraft '63, a former volunteer in Guatemala and later a college recruiter for the Peace Corps, is a political adviser to President Carter. Leonard Levitt '63, who worked in Tanganyika and wrote An African Season, is a journalist. Whit Foster '64 volunteered in Nigeria, worked on the Peace Corps staff in Ghana and Morocco, and now works for the United Nations in Tunisia. Ash Hartwell '63 served in Tanganyika, then came back to teach school in a Washington ghetto, and subsequently went to Uganda as an educational planning expert for UNESCO. Kevin Lowther '63, once a volunteer in Sierra Leone and a Peace Corps officer in Washington, just resigned as editor of the Keene (N.H.) Sentinel to become a field representative in Africa for the Washington-based non-profit organization Africare.

Other former Peace Corps volunteers or staff members who have returned to influence people and policy include Fred Jasperson '61, who has been an economist with AID and the World Bank, Robert Binswanger '52, who has held a variety of top positions in HEW's Office of Education, Paul Tsongas '62, a U.S. Representative from Massachusetts, Henry Homeyer '68, the new director of Peace Corps programs in Mali, and Charles F. "Doc" Dey '52, former dean of the Tucker Foundation and now headmaster at Choate-Rosemary Hall. The list is illustrative, not inclusive.

"Certainly many Dartmouth Peace Corps volunteers are much different than if they had gone directly into the world from Dartmouth." Dawley observed, "and that is certainly worth thinking about."

"I left my job with no regrets or pangs of conscience as to whether it was theright move, only some pity for the men who were stuck there," Joseph Nason '42observed from Saipan, Micronesia, where he is serving as a Peace Corps volunteer.

The pace of life in Sabah is leisurely, Treffle LaFleche '77 reported. "The foodand tropical fruits are priceless. The women are intoxicatingly beautiful...."

Dan Nelson '75 is an assistant editor of the ALUMNI MAGAZINE.

Dan Nelson

-

Feature

FeatureA Delicate Balance

November 1975 By DAN NELSON -

Feature

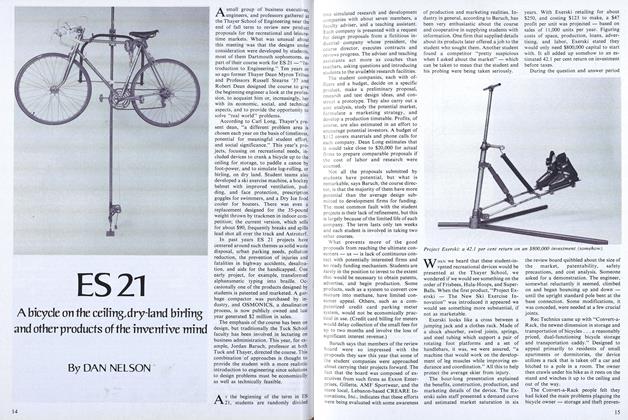

FeatureES 21

January 1977 By DAN NELSON -

Feature

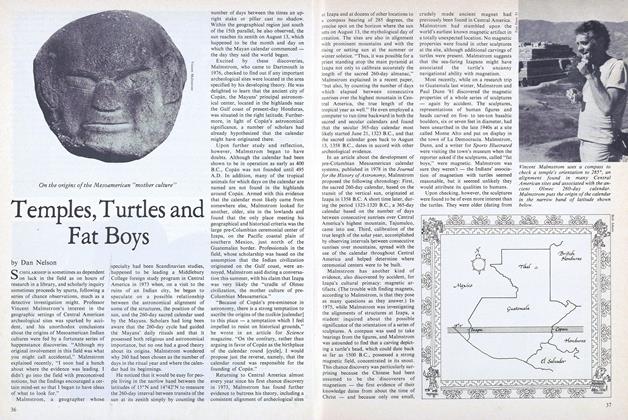

FeatureTemples, Turtles and Fat Boys

September 1979 By Dan Nelson -

Feature

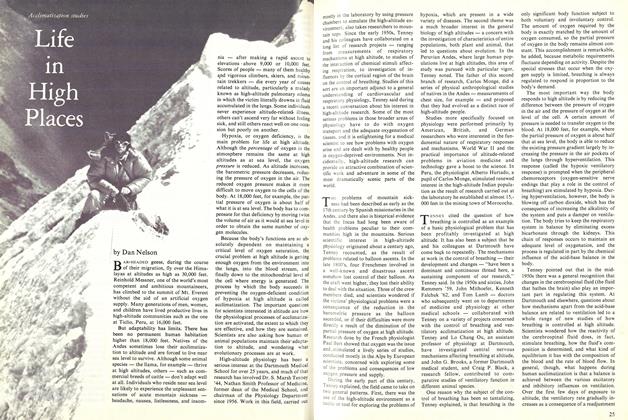

FeatureLife in High Places

April 1980 By Dan Nelson -

Cover Story

Cover StoryIn Two Worlds

May 1980 By Dan Nelson -

Feature

FeatureConjuring Ethics in the Curriculum at Dartmouth

March 1981 By Dan Nelson

Features

-

Feature

FeatureEqual Opportunity

April 1975 -

Feature

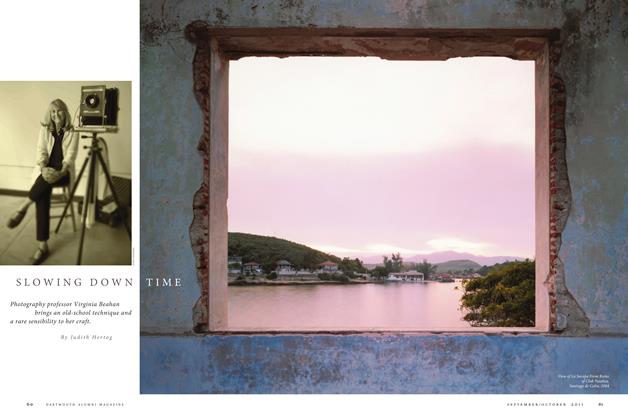

FeatureSlowing Down Time

Sept/Oct 2011 By Judith Hertog -

Cover Story

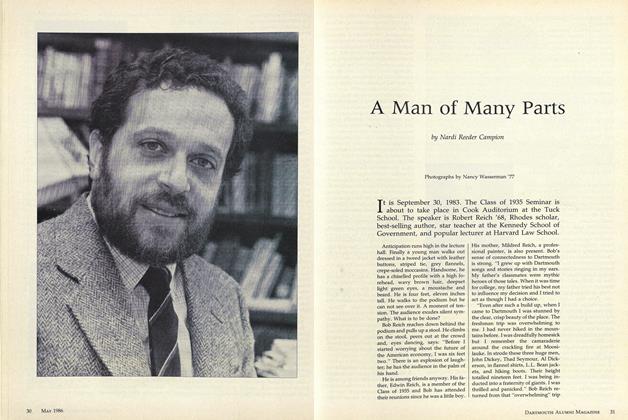

Cover StoryA Man of Many Parts

MAY 1986 By Nardi Reeder Campion -

Feature

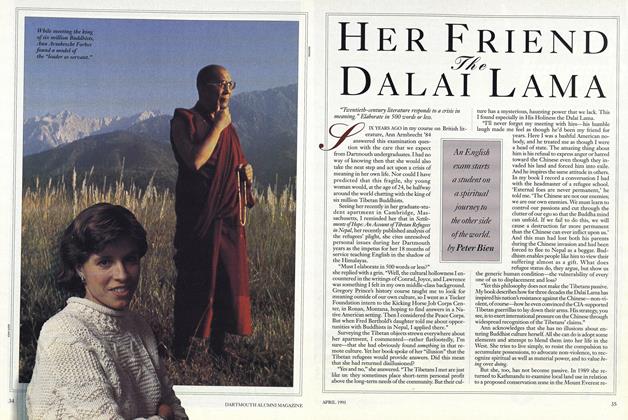

FeatureHer Friend the Dalai Lama

APRIL 1991 By Peter Bien -

FEATURE

FEATUREThe Voice

JULY | AUGUST 2019 By RICK BEYER '78 -

Feature

FeatureBeyond the Glory

Jan/Feb 2010 By SARAH TUETING ’98