Professors Maguire and Malmstad have given us in this publication a new passport to a novelistic continent. Their work is comparable in order of quality and importance to a new translation, fully annotated, of, say, Mannas Magic Mountain or Maria Dabrowska's chronicle of modern Poland, Adventures of aThinking Person. Maguire and Malmstad have provided, that is, ample access to a pioneering work which, with two or three others, stands on a lonely height of 20th-century fiction. Petersburg is one of those few, very few, novels which have broken the "realistic" mold and in the process revealed the texture of an opulent culture at the terminal point of an era.

Boris Nicolaevich Bugayev (1880-1934), a leading Symbolist who wrote verse and fiction under the pen name Andrei Bely, first published his landmark novel in 1913. For Petersburg, however, the term "novel" may be dubious. If even Tolstoy's and Dostoevsky's late novels, relatively conventional in form, struck Henry James as "baggy monsters," what might he have had to say of crowded wildernesses such as Joyce's Ulysses or Bely's equally stunning avant garde cityscape Petersburg?

Petersburg missed having the stunning impact of Ulysses partly because the Russian Revolution destroyed its first public and bred largely yahoos in their place, partly because translations into Western languages have been late, scarce, and flawed. But though the vagaries and compulsions of private memories are the propellants of Ulysses, and history, conspiracy, terror the moving forces of Petersburg, the nihilistic impacts of both novels are strikingly similar. Most conventions of plot, narrative viewpoint, sequentiality, causation, "character drawing," are dissolved in a heaving continuum of simultaneous here-and-now and then-and-there, the stream of consciousness of a human entity who is above and beyond having to decide whether it is author, or character, or surreally animate setting.

Joyce and Bely were the first writers to act out before us in fiction the insight that the time axis along which the "events" of "history" as well as the "experiences" of individuals are imagined to proceed is an abstraction of the human brain in its quest for stylization and manageability. Their artistic intuition enhancing and guiding their intellection, Joyce and Bely furnished the grandest, and still rather dizzying, demonstrations of parallel truths in the individual sphere.

What Dublin was to Joyce, St. Petersburg was to Bely: a planned, rectilinear, autonomous entity and, so to speak, setting. The "plot" of the novel pits a bright, confusedly "radical" young man, Nikolai, armed with a sardine-tin time bomb which ticks away all through the novel, against his bourgeois father, a high official, in an emblematic murder plot. The bomb, to quote from the editors' fine introduction, "is duly delivered to him, the clock mechanism is set to explode within twenty-four hours, and----. But we must not give away the ending: Petersburg is a novel of suspense. It is also a social novel, a family novel, a philosophical, political, psychological, historical novel - and even then we do not begin to exhaust the possible approaches to it."

The similarities between the aim and the achievement of Bely and his close contemporary Joyce are striking and not wholly random. Among other parallels are their panoramic cultural optics, diffuseness in detail of time and form, musical principles of structure, verbal innovation to and beyond normal limits of comprehension. To have come as close as they do, by translation and apparatus, to opening Bely's wilderness to English readers is an achievement of lasting merit for Maguire and Malmstad.

PETERSBURG by Andrei BelyTranslated by Robert Maguire '51and John MalmstadIndiana, 1978. 356 pp. $17.50

Walter Arndt, professor of Russian Languageand Literature, won a Bollingen prize for atranslation of Pushkin. His recent books include translations of Akhmatova's Selected Poems and Goethe's Faust.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

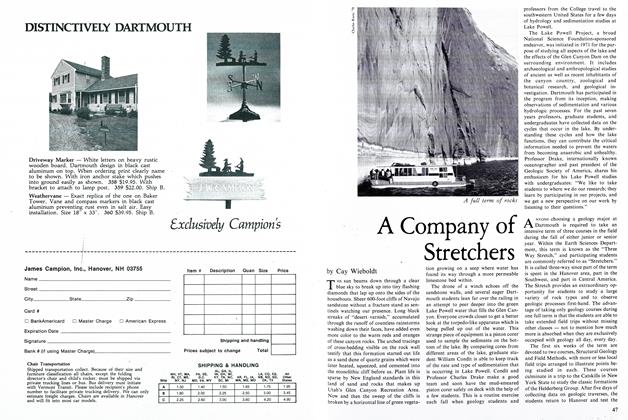

FeatureA Company of Stretchers

September 1978 By Cay Wieboldt -

Feature

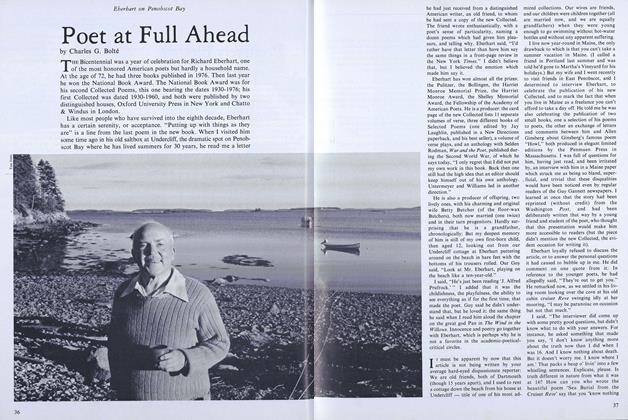

FeaturePoet at Full Ahead

September 1978 By Charles G. Bolte -

Feature

FeatureTHE RIVER and THE DAMS

September 1978 -

Article

ArticleA Journey: Five days to Big Rapids

September 1978 By Dan Nelson -

Article

ArticleDickey-Lincoln: Who wants it? Who needs it?

September 1978 By Greg Hines -

Article

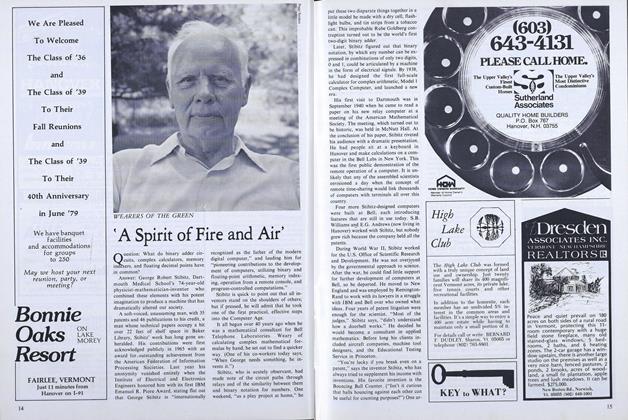

Article'A Spirit of Fire and Air'

September 1978 By NARDI REEDER CAMPION

WALTER W. ARNDT

Books

-

Books

BooksTHE BIG E: The Story of the USS Enterprise

MARCH 1963 By ALBERT L. DEMAREE -

Books

BooksTHE STORY OF ARCHEOLOGY IN THE AMERICAS.

April 1962 By ALFRED F. WHITING -

Books

BooksCOOPERATIVE ADVERTISING

July 1953 By C. N. ALLEN '24 -

Books

BooksTHE CATCH AND THE FEAST.

JANUARY 1970 By FRITZ HIER '44 -

Books

BooksTHE HISTORY OF SEGREGATION.

February 1951 By GEORGE H. KALBFLEISCH -

Books

BooksNEUROLOGY AND PSYCHIATRY FOR GENERAL PRACTICE

May 1951 By NIELS L. ANTHONISEN, M. D.