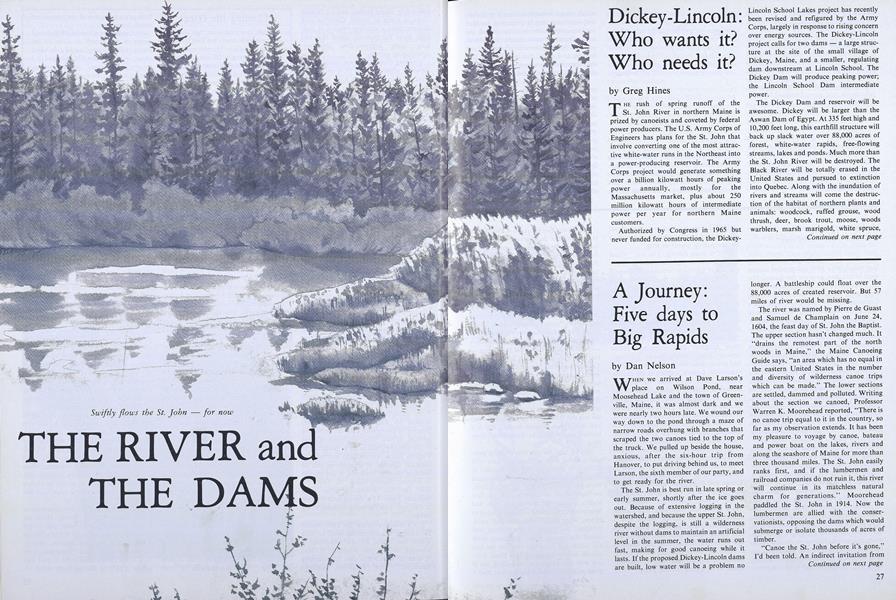

THE rush of spring runoff of the St. John River in northern Maine is prized by canoeists and coveted by federal power producers. The U.S. Army Corps of Engineers has plans for the St. John that involve converting one of the most attractive white-water runs in the Northeast into a power-producing reservoir. The Army Corps project would generate something over a billion kilowatt hours of peaking power annually, mostly for the Massachusetts market, plus about 250 million kilowatt hours of intermediate power per year for northern Maine customers.

Authorized by Congress in 1965 but never funded for construction, the Dickey-Lincoln School Lakes project has recently been revised and refigured by the Army Corps, largely in response to rising concern over energy sources. The Dickey-Lincoln project calls for two dams - a large structure at the site of the small village of Dickey, Maine, and a smaller, regulating dam downstream at Lincoln School. The Dickey Dam will produce peaking power; the Lincoln School Dam intermediate power.

The Dickey Dam and reservoir will be awesome. Dickey will be larger than the Aswan Dam of Egypt. At 335 feet high and 10,200 feet long, this earthfill structure will back up slack water over 88,000 acres of forest, white-water rapids, free-flowing streams, lakes and ponds; Much more than the St. John River will be destroyed. The Black River will be totally erased in the United States and pursued to extinction into Quebec. Along with the inundation of rivers and streams will come the destruction of the habitat of northern plants and animals: woodcock, ruffed grouse, wood thrush, deer, brook trout, moose, woods warblers, marsh marigold, white spruce, tamarack. The list could be expanded.

Habitat destruction sounds innocuous, but what it really amounts to is a net reduction in the number of animals and plants: the arctic woodpecker, the deer, the Canadian lynx, the white-throat sparrow, cedar, lady slipper, and painted trillium. Mobility will not save a species; destruction of habitat brings reduction of numbers, since other areas generally are environmentally incompatible or populated to capacity.

But what's so new here? Man has been pushing plants and animals aside for hundreds of years. If the Army Corps says the Dickey-Lincoln project is economically justified with a satisfactory benefit-cost ratio, doesn't that put an end to the issue? And this is precisely what the more than 30 volumes of report on the Dickey-Lincoln project attempt to establish beyond argument. The economic justification for construction of the Dickey-Lincoln dams rests on the Army Corps' benefit-cost study, which arrays benefits and costs in dollars and concludes that a project is justified economically if the benefits exceed the costs. Dickey-Lincoln passes the benefitcost test by the narrowest of margins, 1.2 benefits to 1 costs. But in reaching 1.2:1, the Army Corps engages in some extraordinary data manipulation.

Note that the Army Corps, which is responsible for the design and construction of the project, prepares the benefit-cost study that recommends the project to Congress for funding. Remember, also, that an above-one benefit-cost ratio, justifies withdrawing resources from private use for public projects, an important incentive for the Army Corps to underestimate costs and pad benefits in reaching the 1.2:1 ratio. For example, in mid-1978, the prime rate of interest - the cost of money for lowrisk private borrowers - was about 8.5 per cent. For purposes of analysis, however, the Army Corps employed interest rates of 3.25 per cent and 6.38 per cent in computing the Dickey-Lincoln benefit-cost ratios. Neither of these interest rates provides a realistic market test for Dickey-Lincoln, and the 3.25 rate is so far from reality that its use can only be an embarrassment even to the most hardened Army Corps champion.

Congress expects benefit-cost analysis to show two things: how a project ranks in comparison with others and whether a particular project is justified economically. In other words, projects with benefit-cost ratios of 2.8:1 and 3.2:1 are clearly superior to a project with a ratio of 1.2:1, although all three pass the benefit-cost test for economic justification. If the ratio is greater than 1, resources employed in the private sector can be shifted to public output without economic loss to society. But for the above-one ratio to be a reliable guide to the optimum private-public resource distribution, project data on benefits and costs must not be under- or overstated. In more cases than not, however, the federal agencies have been better at discovering project benefits than at acknowledging costs. The benefit-cost analysis of the Dickey-Lincoln project continues this tradition.

Early in the 20th century, the Army Corps of Engineers built dams mainly for flood protection. But as years passed and the flood potential lessened as Corps projects were completed, dam building had to be justified on other grounds. Projects were designed to be "multi-purpose," with power production generally the main purpose. Also, other benefits than power have come to be relied upon to justify project development. Recreational opportunities from reservoir use, for example, have frequently added more to the project benefits than flood control, and since the private market does not establish a dollar value for the reservoir use by water skiers and fishermen, Congress has designated the dollar value range of such benefits. To establish recreational benefits, the extent of recreational use of the project - "visitor days" - must be estimated and assigned a value. All visitor days have dollar value, but some kinds of recreational opportunities are worth more than others, depending upon whether the recreational opportunity offered by the project is unusual or commonplace. Recreational benefits for Dickey-Lincoln, according to the Army Corps, fall mainly in the middle range, which critics contend is a totally unjustified attribution of value to a fluctuating slack-water impoundage.

These added benefits usually continue for the life of the project, increase with population growth, and improve the chances of a project passing the benefit-cost test. In addition to recreational benefits, the Dickey-Lincoln benefit-cost ratio is raised by "redevelopment" benefits, which are project outlays for labor that otherwise would be unemployed or underemployed in northern Maine. Redevelopment benefits are not confined to labor expenditures during dam construction, but take account of later operation and maintenance expenditures as well, thus assuming the depressed conditions in the project's labor market will extend beyond the period of construction. Finally, Dickey- Lincoln counts "downstream" benefits of $3.5 million annually for the increase in power availability to the United States from New Brunswick hydroelectric producers. Because Dickey-Lincoln will impound the spring runoff of the St. John River, making this water available for later power generation in New Brunswick as well as in Maine, a credit for the value of the New Brunswick power sold in the United States is added to project benefits. Significantly, however, the benefits but no share in the production costs of this power are attributed to Dickey-Lincoln.

It is clear that the benefit-cost analysis of the Army Corps, although purporting to follow market standards, does not find these standards to be much of a restraint in computing benefits. What about costs? For a project such as Dickey-Lincoln, costs cover the full range of economic goods and services. Some of these costs can be manipulated; that is, adjusted or selected by the analyst. Others simply must be transcribed from market data. The most important single project cost, the interest rate, is at least partially within the control of the federal agencies, since the rate used is adopted by a committee of high-level federal agency representatives. Over the years, this committee has selected an interest rate for project analysis that has been well below the market rate, for example, employing 6.38 per cent in the case of Dickey-Lincoln, when the market rate is about 8.5 per cent. The reason for the lower rate is simple: The lower the interest rate, the easier it is to justify economically a federal project.

The rate of interest enters benefit-cost analysis at two points: as a financing charge during the four or five years of project construction and as a discounting rate to convert the project's future output to present worth. For an economic undertaking to cover full cost - whether public or private, internally or externally financed - it must account for interest during construction, the cost of using moneny in this economic activity. If the interest rate is 6.38 per cent, a smaller cost is incurred than if the rate is 8.5 per cent. Since the Dickey-Lincoln project is capital intensive and the early construction and equipment expenditures dwarf later operation and maintenance costs, the interest rate chosen for analysis exerts a crucial influence on project justification. A low rate means projects pass the benefit-cost test easily; a high rate means they fail.

Discounting, a process which many view as a kind of economic legerdemain, also employs the interest rate to determine the present worth of a project. To compare investments - whether public projects or private business undertakings - the benefits and costs that occur over the life of these investments must be adjusted to the present by discounting. For the capitalintensive project, in which the major cost outlays are for the building of the project but the benefits extend over its later life, the use of a low rate of interest for discounting decreases the benefit stream less than a higher rate. The result: The lower the interest rate for discounting, the higher are benefits relative to costs.

Projects such as Dickey-Lincoln do not pay taxes, which in itself is entirely defensible. But most federal agencies, including the Army Corps, ignore taxes as an element of cost in their analysis; that is, no account is taken in the benefit-cost ratio for such levies as corporation taxes and other outlays that are an inevitable feature of business in the private sector. As a result, the benefit-cost analysis by the agency does not truly reproduce conditions comparable to those of the private economy. If an above-one benefit-cost ratio is to signify a resource use that is equally or more efficient than that of the private sector, the public project must demonstrate a capacity to cover taxes as costs. This does not mean that the Dickey-Lincoln project should actually pay taxes; it does mean, however, that it should be efficient enough to do so.

Few would maintain that the role of government should be limited to functions in which it is equally or more efficient than the private sector. Some things can't be left to private direction and control: national defense, justice, mass education, prevention of poverty, among others. The public interest is not automatically served, however, by federal power production, although it may be justified to subsidize it at times, as in the case of rural electrification. But Dickey-Lincoln does not fulfill any such welfare objective. Under the circumstances, the benefit-cost analysis of Dickey-Lincoln simply conceals from Congress the uneconomic nature of the project by employing a below-market interest rate, neglecting tax costs, padding the benefit stream, and disregarding other sources of power.

Transmission of the Dickey-Lincoln power from its far northern Maine point of production to the Massachusetts market also raises serious environmental and economic considerations. The proposed power line would cut a swath of environmental and aesthetic blight across New England, destroying habitat and promoting the use of herbicides. The transmission route recommended in the draft Environmental Impact Statement would cross northern New Hampshire near Errol, continuing south through Vermont to Boston. An alternate route, not the first choice in the draft report, would bisect the John Sloan Dickey Area in the Dartmouth College Grant, a portion of the Grant recently designated for special protection as a natural area.

How soon can Dickey-Lincoln put power on the market and how much is it needed? Six years after construction starts, if all goes well, Dickey-Lincoln power could be in Boston. In the meantime, power from the James Bay Development Corporation, a Quebec-owned hydroelectric project, will be looking for a market for its output, and there is no place for it to go but the United States. Premier Rene Levesque is anxious to sell ten billion kilowatt hours annually to New England by 1983 - two years before the earliest possible Dickey-Lincoln power. Moreover, ten billion kilowatts of James Bay power annually is over eight times the expected yearly output of Dickey-Lincoln. But if Quebec's price is too high or if we are reluctant to trust the volatile Quebecers - although we have accommodated to an autarchic OPEC - pumped hydro power combined with conventional steam genera- tion near the major market is the obvious lower-cost alternative to Dickey-Lincoln.

At least three alternative pumped-hydro developments are clearly superior to Dickey-Lincoln in terms of benefit-cost ratios - Great Barrington, with a benefit-cost ratio of 1.58:1; Fall Mountain, with 1.67:1; and Percy No. 3, with 1.56:1. These potential developments have the additional advantage of being close to the main power market, thus avoiding extensive construction of new transmission lines. Moreover, the benefit-cost ratios for the pumped hydro installations are computed at an interest rate of ten per cent, a project life of 50 years, and a five per cent tax cost factor. In short, the analysis of the Great Barrington, Fall Mountain, and Percy No. 3 power options imposes substantially higher economic standards than are followed in the case of Dickey-Lincoln and still shows superior benefit-cost results.

How urgent is the need for more power in New England? The frequent reference to the energy crisis, the pleas for conservation of energy, and continued population and economic growth give the impression of an unchecked, burgeoning demand for a shrinking supply of energy. In the long run, New England will face increasing difficulties in meeting its energy needs, but for the short-term - say, the next eight to ten years - there will be no unusual pressure on energy supply sources. Indeed, because of the reduction in power consumption in response to rate increases - price is a great persuader - and because of its moderate growth rate, New England has an exceptionally high electricity reserve. In 1975, for example, New England had an electricity reserve margin of around 50 per cent, compared with a traditional margin of around 20 per cent. This reserve margin will be reduced by future growth in electricity demand, but it affords the opportunity to delay major capital investment decisions in power production facilities.

This reserve margin is reported by the New England Federal Regional Council (NEFRC), an organization made up of representatives of agencies of the federal government that are involved in some way with New England energy problems. The federal agencies in the NEFRC include the Departments of Energy, Interior, Commerce, the Environmental Protection Agency, and - significantly - the Army Corps of Engineers. The NEFRC report of August 1977 forecasts that the average price of electricity in New England will decline in constant dollars between now and 1985. Before rejecting this forecast as simply evidence that the bureaucracy has lost touch with reality, note that this does not mean that electricity rates are going to drop, but that they will not go up as fast as the prices of other goods and services. Electricity rates are forecast to lag behind other prices in large part because of the reserve capacity buffer in New England power production.

But short term or long run, Dickey- Lincoln is economically and environmentally too costly. According to the Army Corps' estimate in 1976 prices, the project will cost more than $822 million, but it is certain that the final figure will top a billion dollars as a result of the usual engineering modifications and price-level increases. By any standard, a billion-dollar investment is impressive, the more so in this case because it is economically unjustified, and even this extraordinary figure does not tell the full story. Environmental destruction does not carry a price tag, but it is an inescapable cost of Dickey-Lincoln power.

Professor Hines has focused his recentstudies on the field of environmentaleconomics. He describes himself as "theoldest but by no means the most conservative member of the economics department."

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureA Company of Stretchers

September 1978 By Cay Wieboldt -

Feature

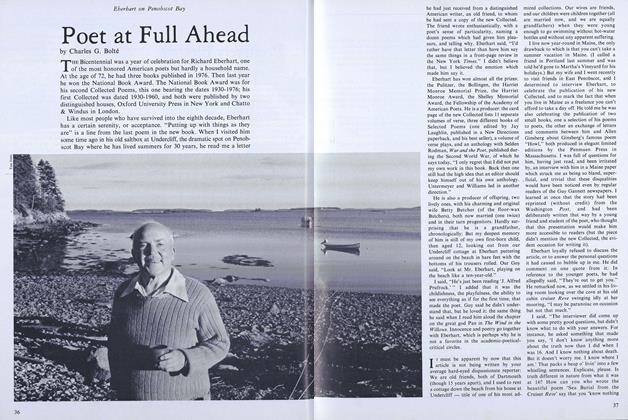

FeaturePoet at Full Ahead

September 1978 By Charles G. Bolte -

Feature

FeatureTHE RIVER and THE DAMS

September 1978 -

Article

ArticleA Journey: Five days to Big Rapids

September 1978 By Dan Nelson -

Article

Article'A Spirit of Fire and Air'

September 1978 By NARDI REEDER CAMPION -

Article

ArticleTennis: The Coach Wore New Underwear

September 1978 By CHRIS CLARK