WHEN we arrived at Dave Larson's place on Wilson Pond, near Moosehead Lake and the town of Greenville, Maine, it was almost dark and we were nearly two hours late. We wound our way down to the pond through a maze of narrow roads overhung with branches that scraped the two canoes tied to the top of the truck. We pulled up beside the house, anxious, after the six-hour trip from Hanover, to put driving behind us, to meet Larson, the sixth member of our party, and to get ready for the river.

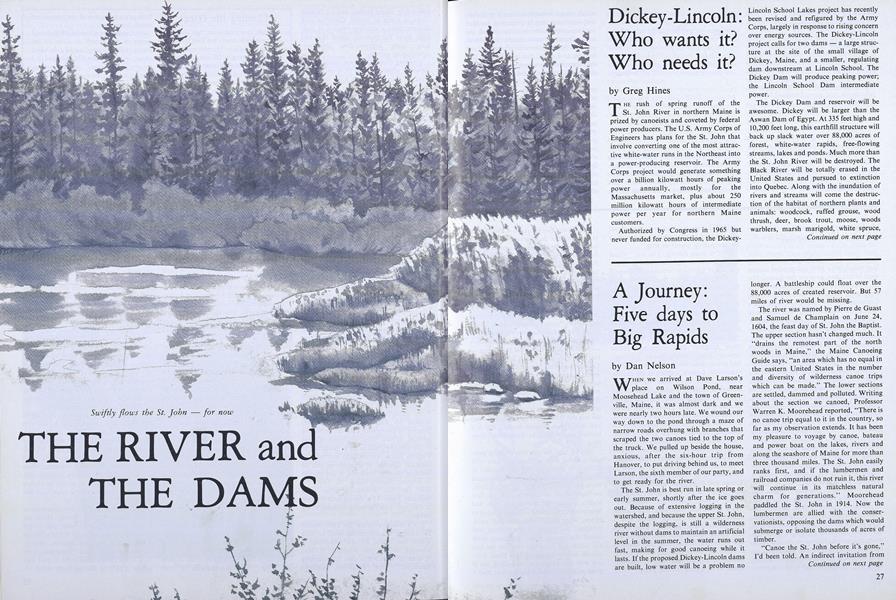

The St. John is best run in late spring or early summer, shortly after the ice goes out. Because of extensive logging in the watershed, and because the upper St. John, despite the logging, is still a wilderness river without dams to maintain an artificial level in the summer, the water runs out fast, making for good canoeing while it lasts. If the proposed Dickey-Lincoln dams are built, low water will be a problem no longer. A battleship could float over the 88,000 acres of created reservoir. But 57 miles of river would be missing.

The river was named by Pierre de Guast and Samuel de Champlain on June 24, 1604, the feast day of St. John the Baptist. The upper section hasn't changed much. It "drains the remotest part of the north woods in Maine," the Maine Canoeing Guide says, "an area which has no equal in the eastern United States in the number and diversity of wilderness canoe trips which can be made." The lower sections are settled, dammed and polluted. Writing about the section we canoed, Professor Warren K. Moorehead reported, "There is no canoe trip equal to it in the country, so far as my observation extends. It has been my pleasure to voyage by canoe, bateau and power boat on the lakes, rivers and along the seashore of Maine for more than three thousand miles. The St. John easily ranks first, and if the lumbermen and railroad companies do not ruin it, this river will continue in its matchless natural charm for generations." Moorehead paddled the St. John in 1914. Now the lumbermen are allied with the conservationists, opposing the dams which would submerge or isolate thousands of acres of timber.

"Canoe the St. John before it's gone," I'd been told. An indirect invitation from Greg Hines, who has taught economics at Dartmouth since 1948 and paddled canoes since before then, gave me the chance. The St. John, for Hines, was familar territory, a, warm-up for a two-week run down the Coppermine in the Northwest Territories later in the summer. His other passion is tennis. I don't know how many racquets he owns, but he has two canoes hanging in his garage, plus a dozen hand-made paddles.

Hines recruited Bob MacArthur '64, the director of the Dartmouth Outward Bound Center and also an Episcopal priest, who recruited me, a canoeing novice. We invited Ed Geehr, a former Dartmouth Medical School student, a specialist in emergency medicine, and a veteran of a previous St. John trip. Geehr invited his "bowperson" Laura Dickson, who came to Hanover as a one-year college exchange student four years ago. Larson, a canoeing cohort of Hines', graduated from Dartmouth in 1952 and teaches political science at the University of New Hampshire. He had spent the previous week at his cabin on Wilson Pond, fishing. I was to be Larson's bowman on the trip.

My white-water canoeing baptism had been with MacArthur on the White River in Vermont, where I had dunked the preacher along with myself. Would Larson mind getting wet? He came booming out of the house, one hand grasping a glass, the other supporting Helen, an emigre from Hanover to Greenville, who was to pick us up at the end of the week when we came off the river. "Where the hell have you been, Hines?" Larson hollered as he barged out into the yard to welcome and admonish us for postponing dinner so long.

"We've been driving, you sot," Hines retorted, "something that in your condition you would be totally incapable of doing."

"Well, you probably can't tell but we've been drinking," Larson admitted, grinning.

Hines, gray-haired and slender, feigned a punch at Larson, burly, red-haired and, after a week in Greenville, unshaven and scraggly. Hines would probably describe himself as wiry; Larson calls him wispy, "the oldest jock in Hanover." The two of them laughed and embraced, Helen between them, trading insults, greetings, and gossip about life in Hanover and life in Greenville. Larson, scoffing at the canoes, paddles, and equipment we brought, shooed us inside to bottles and glasses and a box of stale pretzels. The rest of us, strangers to Wilson Pond, milled about, overwhelmed by the tone of the hospitality, uncertain if we should best be polite by exchanging pleasantries or gibes. Larson, Helen, and Hines, all talking at once, at length agreed, at Hines' insistence, that we ferry over to his island camp to grill steaks.

Dinner was a party to excess, a homecoming for Hines and a reunion with Larson and Helen, who was beside herself with delight at having company from the world beyond Greenville. Afterward, Laura and Geehr went back with Larson while MacArthur, Hines, Helen, and I slept on the island. At least I slept. Hines and Helen talked until late. MacArthur said he fretted. It wasn't the river that was a worry, or the competence of the party, but rather the spirit of what at midnight boded to be a long, six-day party.

A late-May day breaks at 4:30 in Maine. Hines said that the morning mist hanging over Wilson Pond promised a good day for flying from Greenville to Fifth St. John Pond, the last of the ponds forming the headwaters of the St. John, inaccessible except by float plane or a long, upstream paddle with several portages. By 6:30 we were eating breakfast at Larson's - eggs and bacon, seasoned with more of the previous evening's raillery. Larson took off on Hines' "undergraduate" suede saddle shoes, which Hines had worn hoping they'd be noticed. From shoes it went to ancestry - Hines is Irish, Larson is Norwegian - and canoes - Hines has an Old Town, Larsons paddles a Mad River. The debate would have extended to packs, but the two of them discovered they each had purchased the same model from L. L. Bean. Larson is the more assertive character, but Hines is crafty, able to slip the rug out from under an insult and wrap you in it. Hines despises hunting, but in a hunting camp he'd be formidable company.

Sorting food for the trip, packing gear, and making sure we had two cast iron skillets for frying the fish we intended to catch, we regained the momentum mislaid the night before. Despite our precautions, we found when we came to cook the first night's dinner that the skillets also had been mislaid. All of the evidence pointed to Hines, who packed the pots and pans, criticized the weight of the skillets, and touted the virtues of his aluminum cook kit, which did make the trip. At the last minute before leaving Wilson Pond, Larson won my allegiance by lending me a good paddle to replace the six-foot club I brought from Hanover.

It cost $35 apiece to fly the six of us and three canoes from Greenville to Fifth St. John Pond. Our plane could carry only canoes and duffle for four, so Laura and Geehr flew ahead of us, a pattern they followed on the river. We flew in an old Beaver, purchased used by Folsom's Flight Service in 1958. It has logged more than 6,000 hours, a fraction of the time our pilot, "Cranky" Charlie Coe, a veteran of World War II fighters, has reputedly spent in the air. Charlie wore a belt buckle the size of a pancake with "Bush Pilot" stamped on it. He also wore a red baseball cap probably as old as his plane.

The area north of Moosehead Lake looks empty on a map. It looks emptier from the air. After a half-hour flight, Charlie set us down on Fifth Pond and told us to take care. The week before, one of the other pilots had recovered three bodies from Allagash Lake. Wind ana high waves swamped the canoe. The water was too cold for swimming long.

The flies, not the cold, were bothering us. The previous week of hot weather and no rain had warmed the shallow ponds feeding the St. John and had accelerated the hatch. We bolted our lunch, portaged around an old loggers' dam, and started downstream. The north-flowing St. John is a mighty river by the time it is joined by the Allagash and reaches Ft. Kent, 160 miles away on the border of New Brunswick. By the time it flows another 260 miles and reaches the Atlantic it's as wide as the Mississippi and 220 feet deep. But when it leaves the pond where we started it's only a shallow brook, a thin squiggle on even a large-scale map.

I was relieved to discover the first few miles of paddling were not on white water. I had apprehensions of stepping into the canoe and being swept to the ocean. There was a current to contend with, but the riffles were manageable. It , was a beginner's stream the first day, with just enough action to be educational. As a beginner I left my mark - green paint from the bottom of Larson's canoe - on some prominent rocks. Larson was patient.

I was busy untangling my draw stroke from my sweep when we heard a great shouting and splashing from Hines and MacArthur in the lead boat. They had turned a bend to face a choice of two small channels, one on each side of an obvious boulder. As they were deciding, they hung up on a not-so-obvious sleeper, a barely submerged rock, and swung broadside to the current. The upstream side of the canoe tipped, the water rushed in and swamped the boat. None of the gear was lashed to the canoe and everything fell out, including the paddlers and Hines' new waterproof pack, which turned out to be not so waterproof. It did hold water though, as Hines discovered when out of its depths he fished his clothes, binoculars, cameras, and lenses. The clothes dried, the rest was ruined.

While Larson and I, with great discretion and not much valor, slipped through an easy third channel to chase wreckage floating downstream, and while MacArthur and Hines, diving for canned goods, wondered to themselves who was to blame, Laura and Geehr narrowly missed swamping on the same rock that sank our flagship. "My weight in the back was tipping us over," Geehr said later, "so I jumped out." Geehr's dunking helped dry two soggy egos.

As we neared Baker Lake, our destination for the first night and the usual starting point for a St. John trip, the stream slowed, grew deeper and wider, and began to look more like a river. There were fewer deadfalls and logjams to carry around. The last few miles were through open, marshy country where we saw muskrat and beaver, a cow moose, hawks, herons, and loons. Camped on the beach at the head of the lake we heard at sunset the whirring of woodcock as they worked themselves up for mating. "Those horny birds kept me awake all night," Larson said in the morning.

I was awake at 4:30 and fishing at 5:00. By 5:15 I was up to my waist in the water, trying to untangle my lure from the bottom. MacArthur was soon patrolling the beach, too, but neither of us contributed anything to breakfast except our appetites. Our fishing mentor, Larson, ordinarily would have nothing to do with spin-casting, but he left his fly rod at the first portage. Hoping to make the three-mile paddle down Baker Lake before the wind came up, we were underway by 8:00, Larson and I trolling for lunkers with a sure-fire Allagash Supervisor. Maybe it was the name the fish didn't like.

Baker Lake contributes volume to the St. John. Immediately below it are sets of rapids which alternate with sections of smooth water. Wide, shallow sections with riffles are separated by miles of deeper slow water. Laura and Geehr, carrying the lightest load, led most of the way. Hines and MacArthur followed, and Larson and I tended to drag behind, dragging bottom as well. When queried, we pointed to the wooden footlocker, lashed amidships, containing most of the canned goods. The others pointed to the scratched, v-shaped hull of Larson's canoe.

Although breakfast had been finished by 6:30, and lunch, unaccountably, had been postponed until 1:00, the first order of business when we finally stopped was swimming. We had anticipated cold, high water because the ice had broken out two weeks later than usual. What we hadn't counted on was the lack of rain and the week of mid-eighties temperatures before we arrived. During our week on the river the hot dry-spell didn't let up, and the river dropped about four inches a day. Another week, we kept saying to each other, and we'd be walking instead of paddling. Another week and the St. John would be too warm to mix with bourbon.

Lassitude set in after lunch. We paddled for only 20 minutes before deciding to camp on an island below the confluence of the Southwest Branch. "Too hot to continue," we said as we beached the canoes and stripped for swimming. "Tough day tomorrow," was the consensus when we later looked at the map, discovering we were 40 miles from Seven Islands, our prospective third night's campsite. But our schedule was becoming increasingly flexible after two days on the river, the amount of time it takes, we agreed, to relax fully, to remember reasons for coming and to forget what was left behind on the desk.

Stories, frequently but not always canoeing stories, followed dinner every, night. Whatever the topic of conversation, Larson or Hines had a story, typically tangential, to go with it. One story, sometimes only half completed, would lead to another. Geehr and Laura did more listening than talking, even when tempted with bait like "Doctors are a bunch of crooks," or "Did I ever tell you my feminist story?" Attempts to provoke Laura always failed, squashed by her accomplished smile of sarcasm. Mac Arthur, usually addressed as "The Reverend" after dinner, was distinguished by his efforts to salvage serious discussion when it degenerated. "Have you guys ever had a serious conversation in your lives?" he asked once, half in jest, half seriously. "It's very disconcerting."

"Did I ever tell you my mathematics story?" Hines inquired one evening when we were trying to figure how many miles we were from the next set of rapids. "We don't want to hear it. Math is for dullards," Larson cut in. "Easy now," MacArthur objected, "some of us go into theology because we can't do math." "You're just another compulsive Protestant," Hines retorted. "Did I ever tell you my fallen-away Catholic story?"

Hines and Larson did talk seriously one evening, about why certain ethnic groups excel in certain endeavors. "Why," Larson asked, "are there so many Irish writers?" Hines' first response was that "Ireland is a country of low productivity," that there is "nothing to do but drink, talk, and write." The question engendered much speculative discussion, replete with references to obscure but worthy writers and pubs, before Larson succumbed to the temptation to comment on the title of one of Hines' economics books, Persuasion ofPrice. "Persuasion of Price," repeated Larson with a pronounced lilt. "What kind of an Irishman's title is that?"

Because of the previous day's heat, and because we wanted to camp at Seven Islands, we were on the river at 6:30 Monday morning. By 8:00 the temperature was nearing 80. Larson was looking after me, pointing out the holes where he figured the big trout were lurking. My lack of success didn't seem to discourage him. Through each set of rips he asked me how I was reading the river. Where was the most water flowing? On which side of that rock would I go? Later in the day he took the bow and gave me the stern, flinching only occasionally when we bumped or scraped.

While we paddled we kept up an intermittent conversation, the changes in topic punctuated by a mile or two of silent drifting. We'd give Dartmouth and education a mile's worth of talk, marriage and home ownership another two or three, and canoeing and the river mile after mile. "I can't understand why anyone would want to dam this river. What they ought to do with anybody in favor of the dams is make them take this canoe trip," Larson said, with Senator Muskie in mind. "Can you think of any other river in this part of the country that flows this far through this much wilderness?" he asked. "There isn't one. This is the last one."

The river continued to broaden and, as .the stretch of the Connecticut near Hanover was the summer before it was dammed, it was shallow enough to wade across. Although we supposedly paddled 40 miles our third day, it seemed considerably less. We saw a deer crossing the river, another moose and her calf, a number of merganser ducks, an osprey, and more loons. What we didn't see, because there weren't any, were signs of human habitation other than a couple of empty hunting camps and a logging bridge or two. We saw other canoeing parties, but the river wasn't crowded the way the neighboring Allagash usually is.

A mile below the remains of Nine-Mile Bridge, a tough-looking character, a friendly but firm representative of the North Maine Woods Association, beckoned us to shore. Toll for the troll, I guessed. He charged us $14 for the privilege, which we acknowledged it was, of camping on the logging association's land.

I noticed there were more than seven islands as we paddled to the farthest island to camp. A large party camped at one of the upper islands was using 12-foot set poles, normally employed for polling up or snubbing down a river, for vaulting into it. Extensive meadows cover the low-lying islands and the land along the shore. Hines said this place was once farmed to support logging operations. Now the area supports the birds and moose we saw. Since the reservoir created by the Dickey Dam would flood the St. John drainage to a 910- foot elevation, the islands would be under hundreds of feet of water if the dam were approved.

The next day we went through Big Black Rapids, the second-largest rapids on the river. After ten days without rain, the water wasn't as heavy as it had been during previous trips Hines, Larson, and Geehr had taken, but it was heavy enough for me. The way those three approach mediumsized rapids, a bit disconcerting until the rest of us could adapt, is to maneuver to the middle of the channel, stand up in the stern, see where the most water flows, and follow it. I was surprised to find how much the canoe can be controlled in rapids, delighted to learn about back-paddling and ferrying across the current to hold a position, or how to turn 180 degrees and pull into an eddy behind a rock to rest and reconnoiter. It was a great accomplishment, it seemed to me, to slip purposely close by a rock to pick up speed from the heavy water rushing past it.

Big Black, which we had intended to scout, begins innocuously. Larson and I found ourselves in it before we knew where we were. We came around a bend and saw Hines' and Geehr's canoes pulled up on the right bank, the wrong side for scouting, according to the guide book. While we were making up our minds whether or not to join them, we drifted into heavy water and hung up on a rock. Larson said all he could think about was the ignominy of dumping at the head instead of the bottom of the rapids.

Later that day a jet, an FB-111 with missiles slung from the wing, flew over. Hines remarked that we weren't far, as jets fly, from Loring Air Force Base in Limestone, Maine. He said the last death on the St. John occurred in 1975 at Big Rapids, below us yet, when three men from the base decided, after a few beers, that they could all make it through together in one aluminum canoe. Two of them made it, although the canoe didn't, and it took a while to find the body of the third.

Camped at Seminary Brook Tuesday night, our last night on the river, we were visited by another party of six. Feeling protective of our seclusion and of our record of having previous campsites to ourselves, we feigned smiles and greetings while eavesdropping on the group's debate over whether or not to camp with us. Half of them were tired of paddling, the rest wanted to continue and look for another spot. After a narrow vote they departed. When the leader of the tired faction sat down in his canoe, he missed his seat. There was a moment of embarrassed silence before we all laughed and exchanged sincere farewells.

We alternated the cooking and cleaning chores according to canoes. What Geehr and Laura didn't contribute to the daily banter, they made up for in the meals they prepared. They concocted our memorable last supper before Big Rapids. We had hors d'oeuvres of kippered herring, corned beef, and peanut butter on English muffins. The main course consisted of a three-pound, $9 Danish canned ham which had come perilously close to being crossed off the shopping list in Hanover. The ham was smothered with pineapple rings and glazed with raisins and brown sugar. Potatoes, baked in Geehr's reflector oven, and semifresh carrots and peas were served on the side. Dessert was a gingerbread cake laced with bourbon and raisins and topped with chocolate pudding and peanuts. There was pudding left for breakfast. Larson and I had a different culinary style. For dinner one night we opened two cans of beef stew; for breakfast we set out a box of dry cereal.

Big Rapids, according to the guidebook, is "two miles long and very beautiful, constantly dropping among large boulders. CAUTION: This is a very dangerous rapid and several persons have drowned in trying to run it. ... There is one part near the bottom which is difficult in any stage of water and dangerous in high water. ... There is a road on the left if the canoeist decides to carry the rapid."

Stories told by Geehr, Larson, and Hines intimated that the Big Rapids could be frightening. Larson has a story, which Hines says originated in fantasy inspired by terror, about what happened when he acquiesced to his son's suggestion that they ferry across the rapids to try the water on the right-hand side. Larson maintains they were driven up on a ten-foot-high haystack of turbulent water, and that while from the stern he was frantically digging with his paddle to keep the canoe upright, his son in the bow was hanging in space, paddling air. At the last moment, the story goes, they slid off the side into the hole behind the haystack. "All people could see above the waves," Larson concluded, "was the top of my red hat as we bobbed up and down."

Hines has a story about an accomplished friend, a Dartmouth drop-out, whose feat of shooting Big Rapids solo, standing up all the way down, assumes mythic proportions. The best part of the story is when Hines mimics the look on the faces of a more conservative Sierra Club group which witnessed the spectacle.

I don't remember very much about Big Rapids; we went through them so quickly. The three veterans of heavy water tell me the flow was light, "just enough to make things interesting." I remember Larson yelling instructions above the roar, and I remember Hines observing, when we beached our canoes at our pick-up point at the base of the rapids, that "of all the commands in canoeing, the one that is probably the most counterproductive is 'watch that rock!' It sets up terror, panic, and hysteria, since at that moment there are probably 50 to watch for."

It probably isn't practical to follow Larson's suggestion of sending supporters of the dams on a week-long canoe trip. I'd settle for sending them down Big Rapids - if not three to a canoe, at least at high water, just so they'd be familiar with more than electrical current. After running Big Rapids, it might be difficult to watch Dickey Reservoir slowly working its way upstream, spilling over the banks, drowning the St. John. "We'd better slow down," Larson said the last morning of our trip. "We're running out of river."

Dan Nelson '75, an assistant editor of the ALUMNI MAGAZINE, wrote about currentPeace Corps activities in the June issue. Sixweeks after canoeing the St. John, he ledan expedition up Mt. McKinley.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureA Company of Stretchers

September 1978 By Cay Wieboldt -

Feature

FeaturePoet at Full Ahead

September 1978 By Charles G. Bolte -

Feature

FeatureTHE RIVER and THE DAMS

September 1978 -

Article

ArticleDickey-Lincoln: Who wants it? Who needs it?

September 1978 By Greg Hines -

Article

Article'A Spirit of Fire and Air'

September 1978 By NARDI REEDER CAMPION -

Article

ArticleTennis: The Coach Wore New Underwear

September 1978 By CHRIS CLARK

Dan Nelson

-

Feature

FeatureA Delicate Balance

November 1975 By DAN NELSON -

Feature

FeatureHigh On Your Dial

December 1975 By DAN NELSON -

Feature

FeatureShhh. There still are idealists abroad and they're called the Peace Corps

JUNE 1978 By Dan Nelson -

Feature

FeatureTemples, Turtles and Fat Boys

September 1979 By Dan Nelson -

Feature

FeatureLife in High Places

April 1980 By Dan Nelson -

Feature

FeatureHAIR

November 1980 By Dan Nelson

Article

-

Article

ArticleCONGRATULATIONS

March 1935 -

Article

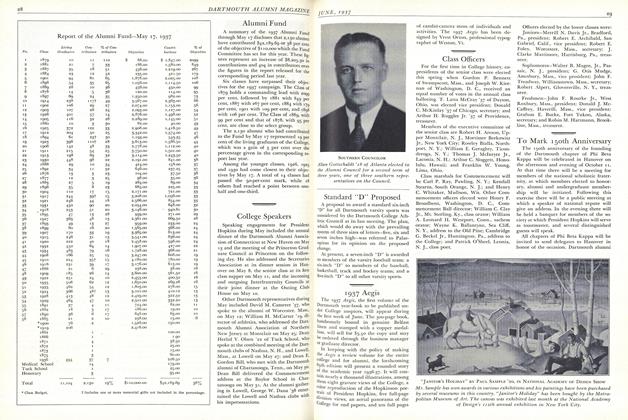

ArticleTo Mark 150th Anniversary

June 1937 -

Article

ArticleCold Dogs

SEPTEMBER 1998 -

Article

ArticlePlants with Attitude

JANUARY 1997 By Cynthia Berger ’79 -

Article

ArticleThe Undergraduate Chair

November 1950 By Peter B. Martin '51 -

Article

ArticleThayer School

November 1954 By WILLIAM P. KIMBALL '29