I had my own reasons for accepting the invitation. It was going to be the first reunion I attended since graduation 16 years ago. I'd been an active undergraduate but was caught up with commitments as an intern at the time of my fifth reunion and as a staff psychiatrist in San Francisco when the tenth came around. But this time we definitely would be there. When the reunion organizing committee contacted me and asked me to prepare a talk for the occasion, I saw a chance to become personally involved again. Yet, the clearer it became to me what thoughts I wanted to share with my classmates, friends, and their wives, the more uncertain I was of my ability to present it in an acceptable and helpful way, and of their capacity to hear what I had to say.

I wanted to talk about manhood at Dartmouth: about our hypermasculine culture,its potential impact on our relationships inlater life, and the fear of homosexuality.

At lunch with some professionalcolleagues the week of the reunion, I tentatively discussed some of my ideas.They'd gone to Yale, Smith, and Harvard.They told me that if I gave such a talk atDartmouth, either my audience woulddesert me or my college years would be recast to discredit me, or both!

Obviously, they were wrong, or I wouldnot be pushing my luck with this submission to the A LUMNI MAGAZINE, with itswider access to the Dartmouth communityand its vocal readership. Since I am addressing the implications of the Dartmouthexperience on relationships in mid-life, Iwill begin by briefly presenting some of thepsychological issues that we all confront inthese years.

L.L.G.

THE middle years of adulthood have attracted a lot of popular and scholarly interest recently, with the publication of Sheehy's Passages, Levinson's Seasons of aMan's Life, and Vaillant's Adaptation toLife. The interest in this subject is impressive considering the general repugnance that greets the term "middle age" and the pervasive doubts regarding life after 30 in our society. The loss of physical youth is often felt as the loss of hope and meaning in one's life, the beginning of inevitable stagnation and decay in which the choices are those of surrender to one's own decline or of looking foolish in self-deluded resistance to one's decline.

Yet, in recent years researchers have identified sequences of psychological growth and development that characterize adulthood in our culture. Specific and predictable issues and milestones are confronted throughout the life cycle, including mid-life. Far from signaling the end of life at 30 (or when bald or noticeably slower on a fastbreak or whatever is one's own tangible marker), these issues chart the course to a meaningful maturity in which self- acceptance and fulfilling relationships are realistically possible. The bottom line is this: People face an identifiable set of developmental tasks at relatively specific times throughout their adult lives, and how well or poorly these are handled has a determining influence on life's subsequent satisfaction.

Some of these issues at mid-life are, I believe, particularly relevant for those of us who have shared the Dartmouth experience. I will highlight three that Levinson describes at greater length in his book.

First, mid-life presents the opportunity to integrate the masculine and feminine aspects of the personality. The concept of masculinity is used here to mean an emphasis on bodily prowess/endurance/ toughness/action/rationality/coldness. "Femininity" refers to those aspects of the self that are tender/nurturant/weak/passive/emotionally responsive. Obviously, I do not mean that men and women are, in reality, so qualitatively polarized. In fact, I mean just the opposite: that both men and women contain the spectrum of these qualities but that these characteristics are culturally thought of as polar "masculine" and "feminine" traits. To try to be 100 per cent masculine is to deny and suppress the inherent potential of the feminine aspects of the self.

In early adulthood, men frequently attempt to subordinate their feminine aspects in the interest of consolidating their identities as men. Mid-life provides the opportunity and challenge to reclaim and develop the dormant feminine potential.

The second mid-life issue I want to focus upon is "mentoring." An older, more experienced individual often serves as a combination teacher-ally-father figure for a younger man. This mentor can become a central force in one's personal and professional development, and such relationships hold great potential on both sides for emotional support and growth as well as for feelings of bitter disappointment and betrayal. Mid-life generally provides the chance to become a mentor, if one is emotionally available and prepared to fulfill this role.

The last mid-life issue I want to highlight is Levinson's notion of "the ladder." By their late thirties, most men begin to evaluate their degree of success in advancing up their occupational hierarchy, and for virtually everyone this ascent of the ladder means dealing with some sense of failure to achieve one's original goals. The pyramidal shape of our corporate and institutional organizations is partially responsible: Apparently, as few as one in twenty makes it from middle-management to corporate leadership. Even those who achieve pre-eminence face some probability of disillusionment, if not at the cost of their victory then at its inability to assure an enduring sense of self-worth. Mid-life may provide the first sobering perspective on the likely outcome of one's attempt to ascend the ladder, and, in this light, offers an opportunity to re-evaluate personal priorities.

WHILE an institution as multi-faceted as Dartmouth has been over the years cannot be fairly described as providing a monolithic "Dartmouth experience," I believe a predominating flavor in the undergraduate culture can be ascertained at given times.

When I reflect on my years at Dartmouth in the early sixties, I recall an all- male college comprised of some 3,000 or so undergraduates, most of whom had the choice of going elsewhere but who selected for themselves this all-male environment. My recollection is that we were far from casual about our masculine identities; in fact, we knowingly selected and then perpetuated and enlarged upon a hypermasculine culture and imagery. All of us can remember our robust cheerleader dressed as an Indian, braving 45-degree weather (and sometimes rain) barechested. Fraternity life specified standards of hard-drinking imperviousness to hazing, to feminine reticence, and, often, to the need to be studious and serious. We wore our hair short, dressed like outdoorsmen, and viewed deviations with suspicion. Our alma mater, in a line that made me squirm even as an undergraduate, describes us as having "the granite of New Hampshire in their muscles and their brains." A friend of mine insists there was even a Dartmouth way to deal with puddles: walk right through them, without rubbers. Our ambitions in relationships with women were addressed in "the real words" to "Dartmouth's In Town Again": "...Our pants are steaming hot, We'll give you all we've got. Virgins are just our meat Rape, rape, rape!" A conscious caricature, surely, but also a sort of cultural ideal, albeit not to be implemented literally.

The expression of emotion, I believe, was similarly codified. It was far more acceptable to be "pissed off' than tearful or confused. I remember crying twice as an undergraduate I hid both times. But anger or physically threatening behavior was tolerated and, to be truthful, even displayed with tacit pride. Feelings of affection and wishes for closeness were problematic. They were acceptable in the context of alcohol, team play, and the structured expectations of fraternity life; outside of these, we learned to tread carefully. "For here we're good fellows/and the beechwood and the bellows/and the cup is at the lip/in the pledge of fellowship."

This depiction of an aspect of the Dartmouth experience that I've termed hypermasculine may sound exaggerated, even distorted. Yet, I believe it captures something implicit and pervasive in my own life at the College, and something, moreover, that I valued very highly. This hypermasculinity was a package solution to the lingering uncertainties about my own manhood that were alive and troublesome in early adulthood. For many of us, it was a profoundly appealing and solidifying contribution to our identities as emerging young men to be able to say and believe "we wear the Dartmouth Green and that's enough" enough to prove we are men and therefore worthy of respect. (I sometimes wonder if gratitude for this timely and valued affirmation of our sense of ourselves is part of the explanation for our noteworthy alumni loyalty and generosity.) Surely we knew that there was a price we were paying in terms of peer pressure to maintain a somewhat rigid and stereotyped persona that often felt artificial and foreign. Yet, we were proud of being notoriously masculine, and, in fact, we were widely envied by peers at other institutions. Some of these on-lookers have admitted to me in recent years that they had thought: "I can't believe those Dartmouth guys are for real with this macho stuff, but what chutzpah they've got" they act like animals, and it works!"

Clearly, this phenomenon was not unique to Dartmouth: It has its roots in our broader culture and in personality development, points to which I will return. But I believe it came together in a notable way at Dartmouth, building upon societal issues, the traditions of the College, and our personal age-specific needs, and providing a backdrop for our lives together.

Still, for all of the utility of this hypermasculinity in terms of affirming ourselves, and developing ideals of leadership and toughness, for all this, ours was a society flavored by intense concern about the feminine aspects of ourselves. And because revealing and expressing these feminine aspects was equated broadly (and erroneously) with unacknowledged or unconscious homosexuality, our culture was permeated with intense anxiety about homosexuality.

What is the evidence for such an assertion? At first, it's not easy to prove. There were no Dartmouth songs that nervously hinted of the danger of insidious homosexuality. Quite the contrary: Our songs were affirmations of manly virtues; our enemies were Crimson, not gay. Yet, I believe the evidence is there: in the memory of my own anxiety, in the hushed memories of others.

I read somewhere that the Eskimos have several words for "snow." At Dartmouth, we had as many names for homosexuals, and each was a term of derogation. I believe that our injunction to dress with conspicuous indifference and always to act "like men" carried an implicit warning: to deviate would be to invite questions about one's true manliness. (Many of us took up the vigil and cautioned offenders; one snide remark was usually enough.) Our enemies from Harvard were derisively seen as effete, in fact, as effeminate.

To me the most cogent evidence lies in our silence and all the noise on the other side. Our private doubts and the loud boasts. Our squeamishness and the overdone doings. Our proclaimed confidence and the constant vigil

In short, we idealized the masculine aspects of ourselves and urgently undertook the wholesale repudiation of the feminine.

Another way of understanding this is to review the issues facing us as new arrivals at the College. We had selected this all-male college with its hypermasculine image (it was there already God knows who started it), and yet had very little opportunity for heterosexual interaction. In fact, we were surrounded by hundreds of other young men. We were anxious. In this setting, a solution was needed, and one in particular was vigorously promoted all around: the hypermasculine myth. The hypermasculine myth went something like this: At Dartmouth the guys are tough, virile, and unbelievably horny, barely contained until their infrequent orgiastic encounters with women. That much was the verbalized common wisdom. The unspoken corollary was: And there is no sexual life or feelings in between, except as part of the build-up for the next blast. No homosexuality. No masturbation. Just a bunch of heterosexual performance machines being charged to their hydraulic limits. And maybe taking out their frustrations with excess aggression on the athletic field, through too much beer drinking, and in sporadic reckless acts of dubious wisdom. These discharge phenomena, naturally, were means of confirming the myth for the individuals involved.

Again, I believe that the urgency surrounding this hypermasculine fear of homosexuality stemmed from the faulty- but-nigh-universal assumption that any thought, feeling, or action arising from the feminine aspect of the self was equivalent to unconscious or unacknowledged homosexuality. We had to be 100 per cent men for fear of a total loss of our treasured masculinity. We had to pretend to be so to avoid the stigma placed on those whose appearance or behavior challenged the hypermasculine myth.

The equivalence of hypermasculinity with undiluted heterosexuality is palpably erroneous, as we all know now and probably suspected then. Men who are violinists, elementary school teachers, and poets are often unambiguously virile while, with some frequency, those who are N.F.L. quarterbacks, jet pilots, and "Marlboro Men" are not. The relationship between one's interpersonal style and sexual orientation is more subtle and less stereotypical than we acknowledged.

THE most obvious and direct result of this skew in our experience at Dartmouth is that many of us left Hanover not only in ignorance of an important dimension of ourselves and one another but also unenlightened regarding women and their needs and capabilities. In our urgency to live a caricature, we tended to view them in complementary modes. Such a need is likely to have enhanced the tendency to dichotomize women, a process sometimes referred to as the madonna/whore split.

In the madonna/whore split, there are two kinds of women: one virtuous, the other sexual. The madonnas are maternal, idealized, and sexually unexciting. The whores are held in contempt; they are good for sexual conquest and as audiences for exhibitionistic display but unthinkable as mothers, sisters, or daughters. Levinson points out that for men who view women through the madonna/whore split, emotional closeness is as impossible with any woman as it is for such men to come to know the feminine aspects of themselves. This is true for their relationships with women as wives, friends, mothers, lovers, bosses, daughters, and subordinates.

(I should add that many women are eager to gain acceptance within the madonna/whore polarity, and they will vigorously insist on the validity of this one-sided picture of themselves and their mates. They seek the security of a ready fit with hypermasculine men, despite the constriction and self-derogation involved. I believe these women are self-hating in the same way that some Jews are among the most virulent anti-Semites and some blacks are masochistically racist.)

Obviously, such rigidities and distortions drastically compromise the chance for fulfilling intimate relations with women or even genuinely congenial associations.

Another direct outgrowth of the fostering of hypermasculinity is a progressively stereotyped and constricted relationship between peers. Competitive posturing and hero worship may be the only available ways of relating to one another, so that superiority at tennis/golf/poker/wealth- accumulation/sexual exploits are all that can be shared, other than vicarious rivalry through professional teams. Not only does this manner of relating to other men greatly impoverish our potential knowledge and enjoyment of each other, but when it does not command our attention by being anxiety-provoking, it often becomes predictable and boring. In mid- life, it may also become a critical handicap.

In mid-life, we all have to deal with the realities implied by Levinson's concept of the ladder. One of the most fruitful ways of escaping the tyranny of the ladder, in which success is everything and failure is catastrophic, is by becoming a mentor; that is, through developing a nurturant relationship to the younger generation in one's field as an alternative to compulsive and desperate rivalry. As a mentor, one maintains ties to youth and avoids obstinate irrelevancy. The mentor can be fulfilled not only by his own narrowly defined acts and accomplishments but through facilitating the growth and achievement of others.

To be a successful mentor requires the capacity to relate in a broadly nurturant, tolerant, emotionally connected, and non- controlling way toward other men it rests on the sufficient development of the mentor's feminine aspects. Uneasiness about closeness to men or demands for competition are intrusive and disruptive. A background of unreflective hypermasculinity may be crippling, thereby cutting off access to a major route toward resolving mid-life issues. Inhibited by the rigid requirements of a hypermasculine identity, such individuals continually try to solve new problems with an old, increasingly inappropriate formula.

Hypermasculinity also directly continues to alienate us from ourselves and fills us with self-doubt. What kind of man am I to cry, to feel overwhelmed, to long to be cared for, to have a homosexual impulse, to be scared, to lack the killer instinct?

Lastly, hypermasculinity inevitably leads to increased anxiety about and rationalized persecution of homosexuals, fostered by the illusion that they are qualitatively unrelated, alien, and defective people.

I certainly think it is possible to overstate the connection between the Dartmouth experience and our hypermasculine attitudes. At one extreme, it would be inaccurate and unfair to blame the institution or impact of the years in Hanover for a constellation of values that is widely distributed and perhaps even predominant in society at large. If Dartmouth men have cultivated a hypermasculine image, so, too, have others of West Point, the Marines, and Tommy's Bar and Grill (ladies invited).

Many factors unrelated to Dartmouth College have favored the growth of hyper- masculinity, but the nature of an article such as this permits only the enumeration of some, without elaboration. The popular culture has well-established commercial and educational imagery that inculcates and reinforces hypermasculine attitudes through television, movies, advertising, and the classroom. The psychological development of boys regularly includes the so-called latency phase that conspicuously features the hatred of girls, the repudiation of feminine traits, the over-drawn identification with manly heroes, and the anticipatory elaboration of rivalries and showing off. This phase solidifies the justresolved oedipal issues, and it prepares the way for the re-working in adolescence of powerful themes in relationship to women and identification with men. Obviously, some of these solutions, appropriate for a nine-year-old latency-aged boy, can be and are carried forward virtually unmodified in the posture of adult hypermasculinity. (I think that is why some men make awful Little League coaches the issues are too intense and real for them.)

At the other extreme, I think it would be needlessly defensive and misleading to fail to acknowledge the ways in which the Dartmouth experience has fostered and legitimized a hypermasculine perspective in many of us. My point in discussing this state-of-mind is, emphatically, not to stigmatize the College or its alumni but to promote the clarification of a problem which, to my knowledge, hasn't been broached in this way. I think one who remains unconvinced by these arguments linking what I have called the Dartmouth experience of the early sixties (and perhaps other eras) to an increased likelihood of difficulties with hypermasculinity still might acknowledge that these difficulties occur with some frequency among us and represent substantial impediments in later life. Others who would agree that their experiences at Dartmouth have fostered these attitudes, or at least retarded their critical examination, might see a special justification for an open discourse in this forum.

My hope is that this communication will lead to a forthright and responsible exchange of ideas and feelings on this subject. I believe an alumni community that could foster a sharing of divergent assessments of the impact of what I have described as hypermasculine culture would become proportionately more open, exciting, and relevant. Exploration of these issues is, in my experience, far more likely to lead to feelings of relief and disburdenment than to lasting shame or confusion. At a minimum, we could hope that reunions could become free of the queasy compulsion to try to recapture or re-enact remnants of a sterile, out-grown past; that new avenues for broader friendship and growth would be possible; and that many gifted and sensitive men who were damaged or turned off by their painful rejections at not meeting hypermasculine standards when undergraduates could come to enrich our associations and realize that we're not so unenlightened and unchanging.

With even greater personal effort and candor we might become better able to accept, value, and find expression for all aspects of ourselves and in the process become more comfortable and authentic fathers, sons, bosses, husbands, friends, subordinates, and mentors. At the risk of sounding corny, we could find broader and richer meaning in our identities as Men of Dartmouth.

A way of walking through puddles

"The Wedding of the Gods Inferno," engraving by Stefano della Bella, 1637; Dartmouth College collections

The American college male was and is givento "high spirits," but some say the artform has been institutionalized at Dartmouth: (top) aftermath of the annual mudbowl; (center) a young man's fancy turnsto beer; (bottom) the Harvard Riot of 1957.

The American college male was and is givento "high spirits," but some say the artform has been institutionalized at Dartmouth: (top) aftermath of the annual mudbowl; (center) a young man's fancy turnsto beer; (bottom) the Harvard Riot of 1957.

The American college male was and is givento "high spirits," but some say the artform has been institutionalized at Dartmouth: (top) aftermath of the annual mudbowl; (center) a young man's fancy turnsto beer; (bottom) the Harvard Riot of 1957.

Besides memories of "soft September sunsets," many can recall the Great Road Trip(top) as a singular rite of passage. Andthere was the football Indian (center) tomanifest maleness to all the world. Andsometimes the girls could watch the fun.

Besides memories of "soft September sunsets," many can recall the Great Road Trip(top) as a singular rite of passage. Andthere was the football Indian (center) tomanifest maleness to all the world. Andsometimes the girls could watch the fun.

Besides memories of "soft September sunsets," many can recall the Great Road Trip(top) as a singular rite of passage. Andthere was the football Indian (center) tomanifest maleness to all the world. Andsometimes the girls could watch the fun.

The freshmen at convocation in 1962: "We had selected this all-male college [and] we had to be 100 per cent men."

Leonard L. Glass M.D. '64 is a clinical instructor in psychiatry at the HarvardMedical School and in the private practiceof psychiatry in the Boston area.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureMonitoring Nature's Big Blow-Up

September 1980 By Dan Nelson -

Cover Story

Cover StoryHorsin' Around

September 1980 By Marsha Belford -

Article

ArticleCombating the Crippler

September 1980 By D.M.N. -

Article

ArticleColor, Charm, Whatever

September 1980 -

Article

ArticleSteel Elected

September 1980 -

Class Notes

Class Notes1940

September 1980 By RICHARD J. GOULDER

Features

-

Feature

FeatureThe Reunion Week

JULY 1959 -

Feature

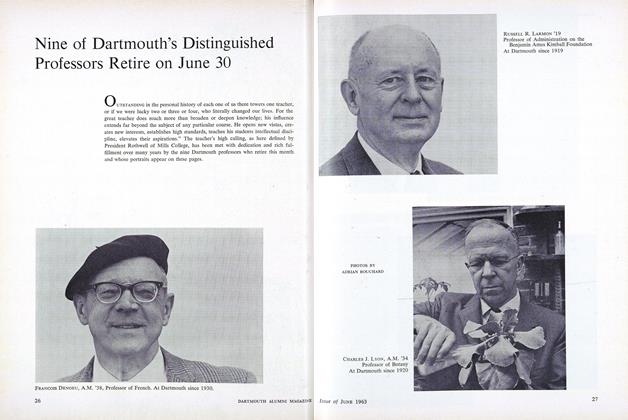

FeatureNine of Dartmouth's Distinguished Professors Retire on June 30

JUNE 1963 -

Feature

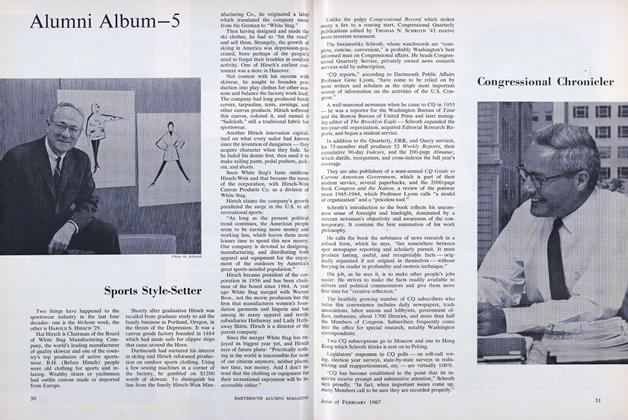

FeatureSports Style-Setter

FEBRUARY 1967 -

Feature

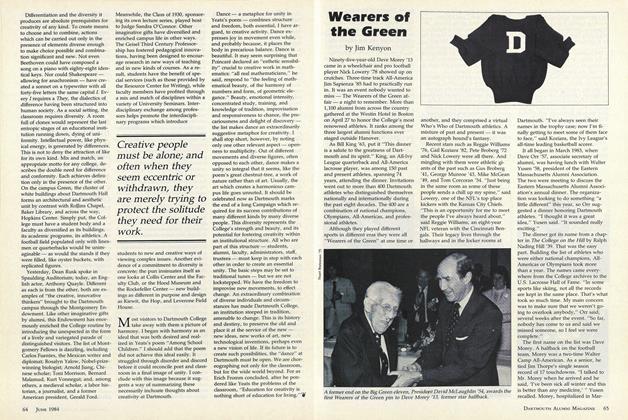

FeatureWearers of the Green

JUNE/JULY 1984 By Jim Kenyon -

Cover Story

Cover StoryHOW TO BUILD YOUR OWN IGLOO

Jan/Feb 2009 By NORBERT YANKIELUN, TH'92 -

Feature

FeatureValedictory to 1967

JULY 1967 By PRESIDENT JOHN SLOAN DICKEY