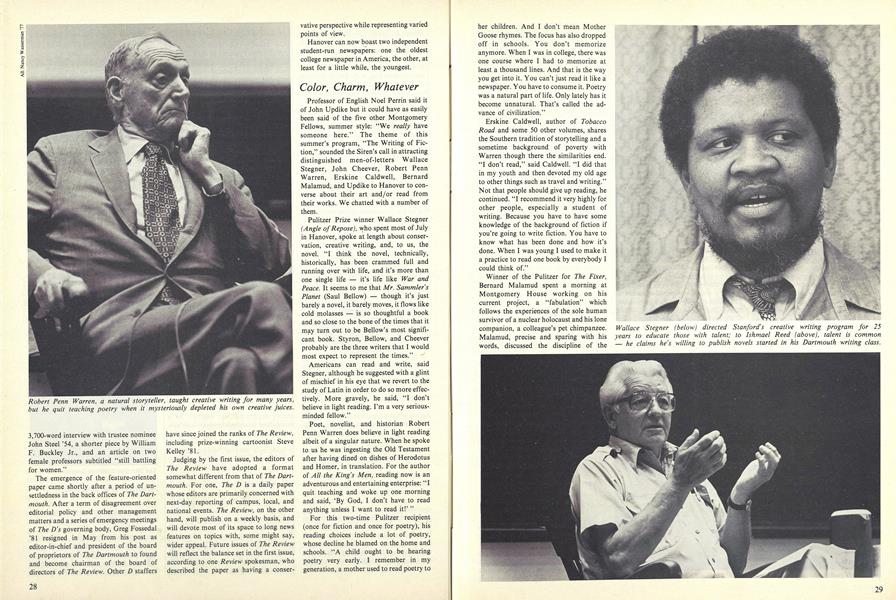

Professor of English Noel Perrin said it of John Updike but it could have as easily been said of the five other Montgomery Fellows, summer style: "We really have someone here." The theme of this summer's program, "The Writing of Fiction," sounded the Siren's call in attracting distinguished men-of-letters Wallace Stegner, John Cheever, Robert Penn Warren, Erskine Caldwell, Bernard Malamud, and Updike to Hanover to converse about their art and/or read from their works. We chatted with a number of them.

Pulitzer Prize winner Wallace Stegner (Angle of Repose), who spent most of July in Hanover, spoke at length about conservation, creative writing, and, to us, the novel. "I think the novel, technically, historically, has been crammed full and running over with life, and it's more than one single life it's life like War andPeace. It seems to me that Mr. Sammler'sPlanet (Saul Bellow) though it's just barely a novel, it barely moves, it flows like cold molasses is so thoughtful a book and so close to the bone of the times that it may turn out to be Bellow's most significant book. Styron, Bellow, and Cheever probably are the three writers that I would most expect to represent the times."

Americans can read and write, said Stegner, although he suggested with a glint of mischief in his eye that we revert to the study of Latin in order to do so more effectively. More gravely, he said, "I don't believe in light reading. I'm a very seriousminded fellow."

Poet, novelist, and historian Robert Penn Warren does believe in light reading albeit of a singular nature. When he spoke to us he was ingesting the Old Testament after having dined on dishes of Herodotus and Homer, in translation. For the author of All the King's Men, reading now is an adventurous and entertaining enterprise: "I quit teaching and woke up one morning and said, 'By God, I don't have to read anything unless I want to read it!'"

For this two-time Pulitzer recipient (once for fiction and once for poetry), his reading choices include a lot of poetry, whose decline he blamed on the home and schools. "A child ought to be hearing poetry very early. I remember in my generation, a mother used to read poetry to her children. And I don't mean Mother Goose rhymes. The focus has also dropped off in schools. You don't memorize anymore. When I was in college, there was one course where I had to memorize at least a thousand lines. And that is the way you get into it. You can't just read it like a newspaper. You have to consume it. Poetry was a natural part of life. Only lately has it become unnatural. That's called the advance of civilization."

Erskine Caldwell, author of TobaccoRoad and some 50 other volumes, shares the Southern tradition of storytelling and a sometime background of poverty with Warren though there the similarities end. "I don't read," said Caldwell. "I did that in my youth and then devoted my old age to other things such as travel and writing." Not that people should give up reading, he continued. "I recommend it very highly for other people, especially a student of writing. Because you have to have some knowledge of the background of fiction if you're going to write fiction. You have to know what has been done and how it's done. When I was young I used to make it a practice to read one book by everybody I could think of."

Winner of the Pulitzer for The Fixer, Bernard Malamud spent a morning at Montgomery House working on his current project, a "fabulation" which follows the experiences of the sole human survivor of a nuclear holocaust and his lone companion, a colleague's pet chimpanzee. Malamud, precise and sparing with his words, discussed the discipline of the writer. A male writer must "get into a room, block out the sun, forget the girl he wants to see, and get to work. It is just sheer professional habituation. It means appearing at the table every day with, or without, inspiration." Occasionally, Malamud reminds himself to leave his work and enjoy the outside world. "Obviously," he stated, "the more experience you have, the better off you are. Everything is grist for the writer's mill." But, he said, someone who really wants to learn to write should "stay home and read."

John Updike, a National Book Award winner for The Centaur, enjoys the rare opportunities he gets to read for pleasure's sake. He will pick up factual books, anything about golf, new works by Cheever, Malamud, Roth, and very few others, and poetry. "I read all the poetry in The New Yorker," said Updike, "and I read it first. But I can't quite explain it, because I rarely go out of my way to read a book of poems. Don't much like the poetry I read, but I seem to like the idea of poetry in general. And have not entirely given up myself on writing it. I read poetry because you can read it in a short time. It does offer you a language trying to operate on a high energy level. My theory about prose is that it should also give us something of this linguistic delight as it goes along and says that 'Gertrude left the room' or 'Harold entered in.' But there should be something on the page other than Gertrude and Harold running in and out of doors, some kind of abstract color, charm, whatever."

"Poetry," he continued, "used to be about the non-human world, about what is called nature. Now, when there's less and less nature, it's being crowded into the corners of our lives. Poetry seems to be about a kind of gray, urban existence that, to me, rarely can be made to elicit what I think of as poetic qualities. It's a little like the machine at the bottom of the ocean that keeps making salt. There is a machine somewhere that keeps making poetry. But it's not a poetry we need."

John Cheever, a Pulitzer winner for his collected stories, slipped in and out of town before we had a chance to talk with him, but we heard that he displayed his usual magnanimity toward his fellow writers. The literary world today, he said, "is an extraordinarily peaceable kingdom." He didn't hear what we heard.

Stegner had this to say about Norman Mailer: "I've been watching Norman for a long time. He was briefly a student of mine at Harvard before the war. He was obviously very concerned to make it in some fashion which seems to me to have been somewhat bemused by his own image. And image is a bad thing to be bemused by." He called Mailer's The Executioner's Song "another instance of Norman's choosing a subject which is bound to be in the public eye, as if in order to make his quarter of a million a year, or whatever he needs, he had to pick that subject. And that's kind of pitiful. That's a sort of slavery."

Warren said of Eudora Welty: "I like her novels but I don't think they have the gutsiness of her stories. She has a wonderful command of language. She's a marvelous writer. It doesn't diminish her to say that she hasn't the scale of Faulkner or Dreiser."

Ishmael Reed, this summer's Writer-in- Residence, criticized Malamud: "I read Malamud's book Dubin's Lives, and I thought it was like the average pulp romance you find in the drugstore with a lot of pretentious learning thrown in. I thought I was going to read a highfalutin novel. Here's a man who says he works all day on a sentence. I thought a lot of sentences were pretty prosaic."

Caldwell castigated contemporary writers: "Right now there's a great surge of pornography. Everybody thinks he has to be a little more pornographic than the book that was published five minutes ago in order to be successful. Pornography is always in the past, there's no future to it.

"Nowadays you write one story or one book and the first thing you know you get an offer from an advertising agency or you get a movie contract or TV or something or other. That dissipates your whole existence right away. You're no longer interested in what you were doing because now the money is the important thing."

Reed spent the summer in Hanover as a visiting professor in the African and Afro- American Studies Program. A poet (Conjure), novelist (Mumbo Jumbo), and publishing entrepreneur (Before Columbus Foundation), Reed said of the summer's Montgomery Fellows: "It's interesting that they were all white male writers who write pretty much the same way. There wasn't any variety." Reed called for more diversity in America's reading and education, an end to the mono-cultural and the adoption of the multi-cultural learning experience. "All of us have read the Bronte sisters, have read Thomas Mann, have read Dostoevsky. What you find with the older novelists is that there is a tendency to say your generation was the best and the writers you read in school were the best writers and nobody has been able to approach that. Even though you haven't read around much. I read a lot of women writers, a lot of Chicano writers, Native American writers, and these are points of view that I think one has to know in order to get a real understanding of America."

Wallace Stegner (below)

directed Stanford's creative writing program for 25years to educate those with talent; to Ishmael Reed (above), talent is commonhe claims he's willing to publish novels started in his Dartmouth writing class.

Rosenthal and Berry: reporters, writers, and "Undergraduate Chair" columnists.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureThe Dartmouth Animal and The Hypermasculine Myth

September 1980 By Leonard L. Glass -

Feature

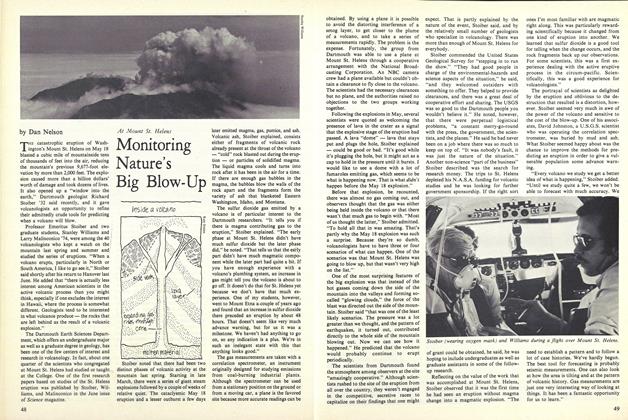

FeatureMonitoring Nature's Big Blow-Up

September 1980 By Dan Nelson -

Cover Story

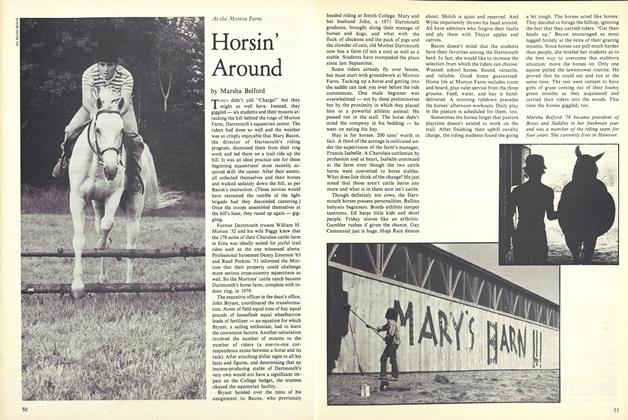

Cover StoryHorsin' Around

September 1980 By Marsha Belford -

Article

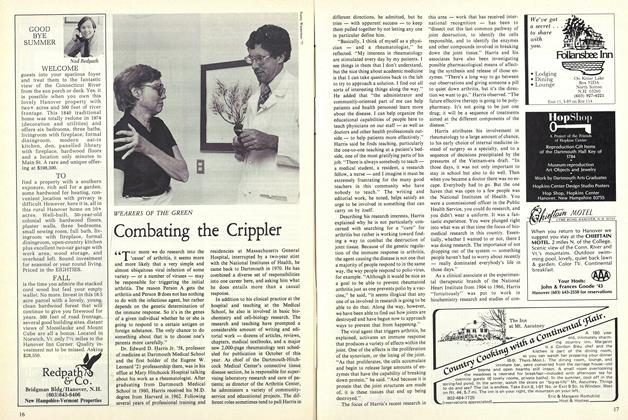

ArticleCombating the Crippler

September 1980 By D.M.N. -

Article

ArticleSteel Elected

September 1980 -

Class Notes

Class Notes1940

September 1980 By RICHARD J. GOULDER

Article

-

Article

ArticleCalendar of Meetings of Committee on Education

January, 1912 -

Article

ArticleENLISTMENT OF ENGINEERING STUDENTS

January 1918 -

Article

ArticleNew Constitution Adopted for Athletic Council

March 1935 -

Article

ArticleMemorial Field, June 1938

February 1940 -

Article

ArticleAlumni Fund Passes $175,000

June 1945 -

Article

ArticleOn Being Involved

OCTOBER, 1908