"THE more we do research into the 'cause' of arthritis, it seems more and more likely that a very simple and almost ubiquitous viral infection of some variety or a number of viruses may be responsible for triggering the initial arthritis. The reason Person A gets the arthritis and Person B does not has nothing to do with the infectious agent, but rather depends on the genetic determination of the immune response. So it's in the genes of a given individual whether he or she is going to respond to a certain antigen or foreign substance. The only chance to do something about that is to choose one's parents more carefully."

Dr. Edward D. Harris Jr. '58, professor of medicine at Dartmouth Medical School and the first holder of the Eugene W. Leonard '21 professorship there, was in his office at Mary Hitchcock Hospital talking about his work as a rheumatologist. After graduating from Dartmouth Medical School in 1960, Harris received his M.D. degree from Harvard in 1962. Following several years of professional training and residencies at Massachusetts General Hospital, interrupted by a two-year stint with the National Institutes of Health, he came back to Dartmouth in 1970. He has combined a diverse set of responsibilities into one career here, and asking him what he does entails more than a casual response.

In addition to his clinical practice at the hospital and teaching at the Medical School, he also is involved in basic biochemistry and cell-biology research. The research and teaching have prompted a considerable amount of writing and editorial work dozens of articles, reviews, chapters, medical textbooks, and a major new 2,000-page rheumatology text scheduled for publication in October of this year. As chief of the Dartmouth-Hitch- cock Medical Center's connective tissue disease section, he is responsible for supervising laboratory research and care of patients; as director of the Arthritis Center, he administers a variety of community- service and educational projects. The different roles sometimes tend to pull Harris in different directions, he admitted, but he tries with apparent success to keep them pulled together by not letting any one in particular define him.

"Basically, I think of myself as a physician and a rheumatologist," he reflected. "My interests in rheumatology are stimulated every day by my patients. I see things in them that I don't understand, but the nice thing about academic medicine is that I can take questions back to the lab to try to approach a solution. I find out all sorts of interesting things along the way." He added that "the administrator and community-oriented part of me can help patients and health personnel learn more about the disease. I can help organize the educational capabilities of people here to teach physicians on our staff as well as doctors and other health professionals outside. to help patients more effectively." Harris said he finds teaching, particularly the one-to-one teaching at a patient's bedside, one of the most gratifying parts of his job. "There is always somebody to teach a medical student, a resident, a research fellow, a nurse and I imagine it must be extremely frustrating for the many good teachers in this community who have nobody to teach." The writing and editorial work, he noted, helps satisfy an urge to be involved in something that can carry on by itself.

Describing his research interests, Harris explained why he is not particularly concerned with searching for a "cure" for arthritis but rather is working toward finding a way to combat the destruction of joint tissue. Because of the genetic regulation of the immune response in arthritis, the agent causing the disease is not one that a majority of people respond to in the same way, the way people respond to polio virus, for example. "Although it would be nice as a goal to be able to prevent rheumatoid arthritis just as one prevents polio by a vaccine," he said, "it seems illogical that any one of us involved in research is going to be able to do that. Along the way, however, we have been able to find out how joints are destroyed and have begun now to approach ways to prevent that from happening."

The viral agent that triggers arthritis, he explained, activates an immune response that produces a variety of effects within the joint. One of the effects is the proliferation of the synovium, or the lining of the joint. "As that proliferates, the cells accumulate and begin to release large amounts of enzymes that have the capability of breaking down protein," he said. "And because it is protein that the joint structures are made of, it is these tissues that end up being destroyed."

The focus of Harris's recent research in this area work that has received international recognition has been to "dissect out this last common pathway of joint destruction, to identify the cells responsible, and to identify the enzymes and other compounds involved in breaking down the joint tissue." Harris and his associates have also been investigating possible pharmacological means of affecting the synthesis and release of those enzymes. "There's a long way to go between our observations and giving someone a pill to quiet down arthritis, but it's the direction we want to go," Harris observed. "The future effective therapy is going to be polypharmacy. It's not going to be just one drug; it will be a sequence of treatments aimed at the different components of the disease."

Harris attributes his involvement in rheumatology to a large amount of chance, to his early choice of internal medicine instead of surgery as a specialty, and to a sequence of decisions precipitated by the pressures of the Vietnam-era draft. "In those days, it was not only important to stay in school but also to do well. Then when you became a doctor there was no escape. Everybody had to go. But the one haven that was open to a few people was the National Institutes of Health. You were a commissioned officer in the Public Health Service, you could do research, and you didn't wear a uniform. It was a fantastic experience. You were plunged right into what was at that time the focus of biomedical research in this country. Essentially, whether I wanted to or not, there I was doing research. The importance of not dropping out of the system something people haven't had to worry about recently really dominated everybody's life in those days."

As a clinical associate at the experimental therapeutic branch of the National Heart Institute from 1964 to 1966, Harris "fortuitously" was put to work in biochemistry research and studies of connective tissues. "I had been interested in cardiology," he said, "and I would have chosen that as my specialty had it not been for this research experience. 'Look,' I said to myself, 'you can't waste this. You have to do something that's related.' Rheumatology seemed like the best idea." He went back to Harvard as an instructor and joined the arthritis unit at Massachusetts General Hospital, where he worked with Dr. Stephen Krane, head of the rheumatology department and Harris's mentor and collaborator on a number of research projects. "After a while," Harris noted, "we worked so closely together that it became hard to tell whose ideas were whose. I don't know if it bothered him, but I decided I had to see if I would sink or swim on my own." He and his wife Mary Ann, daughter of the late secretary of the College, Sid Hayward, moved back to Hanover ten years ago and Harris joined the faculty of the Medical School and staff of Mary Hitchcock Hospital. He became a full professor in 1977 and director of the new Arthritis Center the same year.

He described the Arthritis Center, one of 22 similar centers throughout the country, as "a name given to a group of ideas and projects designed to further research about arthritis and to expand the capacity of this place for carrying out innovative programs and educational projects in the community." The center involves community physicians, social workers, nurses, physical and occupational therapists, and lay people. It serves most of New Hampshire and much of Vermont and is about to extend some of its educational programs into Maine. Although patients come to the center for treatment there is a new pediatric rheumatology program, for example a large part of the center's work is aimed at getting the latest word about arthritis out of the office, at training other doctors and health workers, and at supporting a number of "arthritis clubs" in communities throughout the region. The idea is to help build competence in dealing with arthritis at other health centers so that they can carry on independently, to increase general knowledge about arthritis, and to disseminate expertise and information. Last year the center's activities were assured of funding for the next several years, a vote of confidence Harris attributes largely to the staffs work in thoroughly evaluating the various programs it conducts.

Arthritis has been called the nation's major crippling disease. From three to five per cent of the population has some form of degenerative joint disease; between one and two per cent of the population has rheumatoid arthritis, according to Harris. Asked if the proliferation of misinformation, folk remedies, and so-called miracle cures are a large obstacle to the center's educational efforts, Harris agreed that there is a "certain element in all of us that responds to a supposed easy cure." "But you can't look at it as a failure of your educational program when people try these things," he added. "You just hope people aren't hurt by them, that they don't cost too much, and that they don't interfere with other therapy. If the patient wants to take honey and lemon juice, drink herb tea, and wear a copper bracelet, fine. Just so long as the patient understands the disease and can also accept proper treatment. We can do something for almost everyone who comes in here." A couple of years ago, in a long letter to the editor of Country Journal, written in response to an article about bee-sting therapy for arthritis, Harris concluded:

I am one of many physicians who believes in patient "self-help." So many of our patients have pain without an organic basis. If a bee sting could help them, I would be pleased. If a stronger faith, a better home life, a new job could help them, I'd be pleased. If I could help them with words and medication, I'd be pleased. Many sufferers from "arthritis" have pain but not arthritis and before we can attribute a beneficial effect to bee-sting therapy for arthritis, it must be demonstrated on patients who benefit from the stings and, indeed, have arthritis. I say this particularly strongly for those many people with true deforming rheumatoid arthritis who haven't been helped by me or rheumatologists like me, by bee stings, vinegar and honey, or fish diets, or anything else. These are the folks that need our cure.

The greatest worries of people who have arthritis are about the pain and loss of function they will experience, Harris said. "Our response is to help the patient recognize that the pain reflects inflammation of the joint and that the loss of function reflects a process of joint destruction. These are the two components of the disease that we try to slow down by using medicine, occupational and physical therapy, and the mental variety of treatment. The last point isn't trivial. The patient's involvement in his or her destiny is very important. We feel the best way to generate good treatment is to have the patient understand the disease and to participate in its treatment. With a good understanding of the disease and the treatment, the patients do better. They really do."

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureThe Dartmouth Animal and The Hypermasculine Myth

September 1980 By Leonard L. Glass -

Feature

FeatureMonitoring Nature's Big Blow-Up

September 1980 By Dan Nelson -

Cover Story

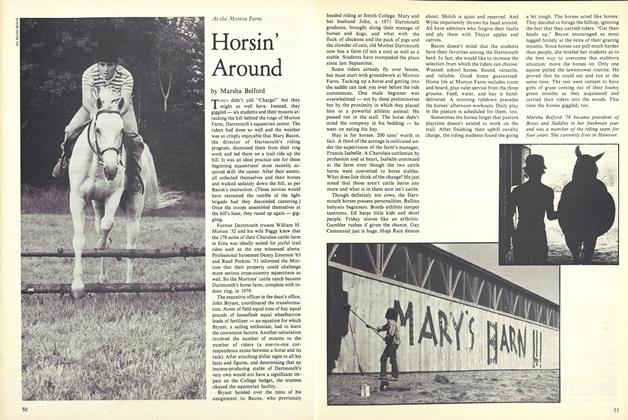

Cover StoryHorsin' Around

September 1980 By Marsha Belford -

Article

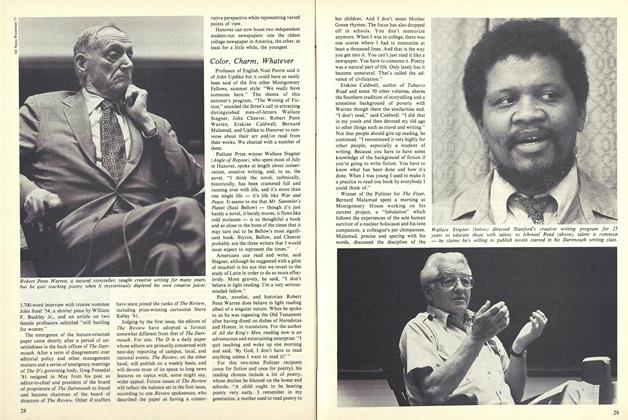

ArticleColor, Charm, Whatever

September 1980 -

Article

ArticleSteel Elected

September 1980 -

Class Notes

Class Notes1940

September 1980 By RICHARD J. GOULDER

D.M.N.

-

Article

ArticleWorking with the Grain: Weed's Way with Students and Wood

December 1976 By D.M.N. -

Article

ArticlePaddler, Climber, 4-term Planner

May 1977 By D.M.N. -

Article

Article'Abounding In Hot Grace'

NOV. 1977 By D.M.N. -

Article

ArticleClean Sweeper

DEC. 1977 By D.M.N. -

Article

ArticleSignal-Caller for the Hurt

October 1978 By D.M.N. -

Article

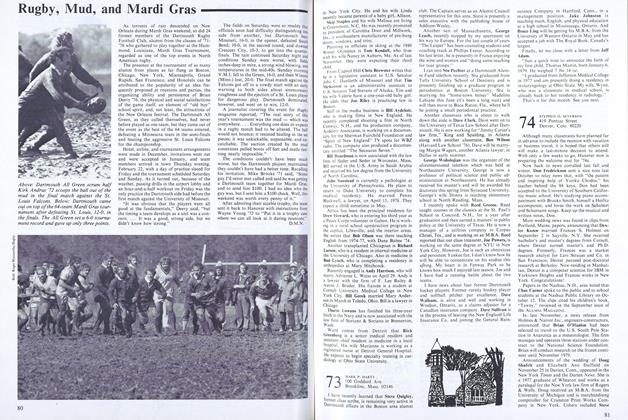

ArticleRugby, Mud, and Mardi Gras

May 1979 By D.M.N.

Article

-

Article

ArticlePRICE OF COMMONS BOARD REDUCED FOR NEXT SEMESTER

January 1921 -

Article

ArticleWINTER CARNIVAL DATES EARLY IN FEBRUARY

January, 1926 -

Article

ArticleBIG GREEN FOOTBALL NEWS

June 1960 -

Article

ArticleLAST NIGHT

November 1938 By A. A. McKenzie '32 -

Article

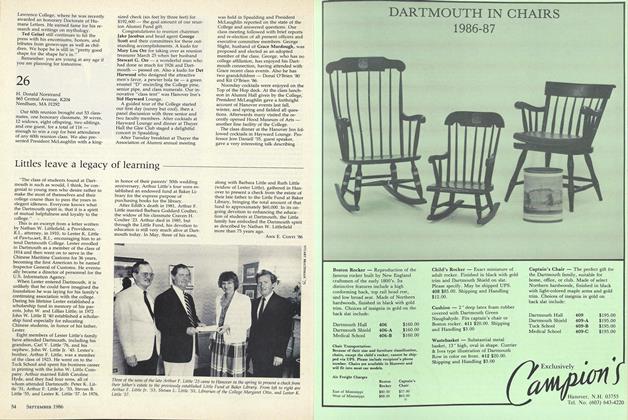

ArticleLittles leave a legacy of learning

September 1986 By ANN E. CONTI '86 -

Article

ArticleMIND VERSUS BRAIN

November, 1930 By President Hopkins