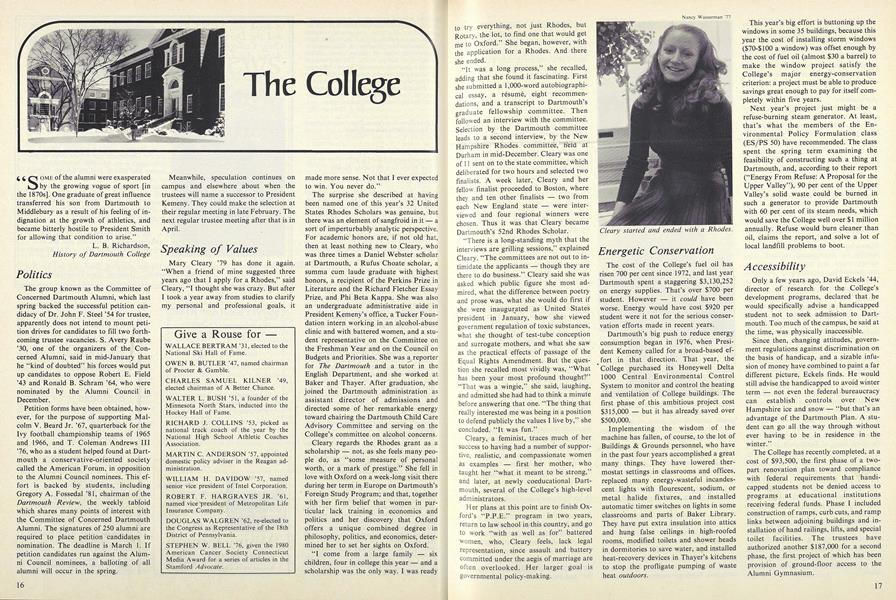

Mary Cleary '79 has done it again. "When a friend of mine suggested three years ago that I apply for a Rhodes," said Cleary, "I thought she was crazy. But after I took a year away from studies to clarify my personal and professional goals, it made more sense. Not that I ever expected to win. You never do."

The surprise she described at having been named one of this year's 32 United States Rhodes Scholars was genuine, but there was an element of sangfroid in it a sort of imperturbably analytic perspective. For academic honors are, if not old hat, then at least nothing new to Cleary, who was three times a Daniel Webster scholar at Dartmouth, a Rufus Choate scholar, a summa cum laude graduate with highest honors, a recipient of the Perkins Prize in Literature and the Richard Fletcher Essay Prize, and Phi Beta Kappa. She was also an undergraduate administrative aide in President Kemeny's office, a Tucker Foundation intern working in an alcohol-abuse clinic and with battered women, and a student representative on the Committee on the Freshman Year and on the Council on Budgets and Priorities. She was a reporter for The Dartmouth and a tutor in the English Department, and she worked at Baker and Thayer. After graduation, she joined the Dartmouth administration as assistant director of admissions and directed some of her remarkable energy toward chairing the Dartmouth Child Care Advisory Committee and serving on the College's committee on alcohol concerns.

Cleary regards the Rhodes grant as a scholarship - not, as she feels many people do, as"some measure of personal worth, or a mark of prestige." She fell in love with Oxford on a week-long visit there during her term in Europe on Dartmouth's Foreign Study Program; and that, together with her firm belief that women in particular lack training in economics and politics and her discovery that Oxford offers a unique combined degree in philosophy, politics, and economics, determined her to set her sights on Oxford.

"I come from a large family six children, four in college this year and a scholarship was the only way. I was ready to try everything, not just Rhodes, but Rotary, the lot, to find one that would get me to Oxford." She began, however, with the application for a Rhodes. And there she ended.

"It was a long process," she recalled, adding that she found it fascinating. First she submitted a 1,000-word autobiographical essay, a resume, eight recommendations, and a transcript to Dartmouth's graduate fellowship committee. Then followed an interview with the committee. Selection by the Dartmouth committee leads to a second interview, by the New Hampshire Rhodes committee, held at Durham in mid-December. Cleary was one of 11 sent on to the state committee, which deliberated for two hours and selected two finalists. A week later, Cleary and her fellow finalist proceeded to Boston, where they and ten other finalists two from each New England state were interviewed and four regional winners were chosen. Thus it was that Cleary became Dartmouth's 52nd Rhodes Scholar.

"There is a long-standing myth that the interviews are grilling sessions," explained Cleary. "The committees are not out to intimidate the applicants though they are there to do business." Cleary said she was asked which public figure she most admired, what the difference between poetry and prose was, what she would do first if she were inaugurated as United States president in January, how she viewed government regulation of toxic substances, what she thought of test-tube conception and surrogate mothers, and what she saw as the practical effects of passage of the Equal Rights Amendment. But the question she recalled most vividly was, "What has been your most profound thought?" "That was a wingie," she said, laughing, and admitted she had had to think a minute before answering that one. "The thing that really interested me was being in a position to defend publicly the values I live by," she concluded. "It was fun."

Cleary, a feminist, traces much of her success to having had a number of supportive, realistic, and compassionate women as examples first her mother, who taught her "what it meant to be strong," and later, at newly coeducational Dartmouth, several of the College's high-level administrators.

Her plans at this point are to finish Oxford's "P.P.E." program in two years, return to law school in this country, and go to work "with as well as for" battered women, who, Cleary feels, lack legal representation, since assault and battery committed under the aegis of marriage are often overlooked. Her larger goal is governmental policy-making.

Cleary started and ended with a Rhodes.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureLove and War Among the Ivies

January | February 1981 By Keith Bellows -

Cover Story

Cover StoryStranger in the Land

January | February 1981 By Rob Eshman -

Article

ArticleMagic in the Museum

January | February 1981 By Shelby Grantham -

Class Notes

Class Notes1948

January | February 1981 By FRANCIS R. DRURY JR. -

Class Notes

Class Notes1965

January | February 1981 By ROBERT D. BLAKE -

Article

ArticleNazi Hunter

January | February 1981 By David M. Shribman'76

Article

-

Article

ArticleJAMES M. REID '24 UNDERGRADUATE EDITOR

November, 1922 -

Article

ArticleFACULTY ADOPTS NEW LANGUAGE REQUIREMENTS

April 1926 -

Article

ArticleAlumni Council Meeting

November 1946 -

Article

ArticleTuck Overseers

DECEMBER 1972 -

Article

ArticleTennis

May 1955 By Cliff Jordan '45 -

Article

ArticleThe Price of Excellence

MAY 2000 By President James Wright