SAINT A UG USTINE'S PIGEON by Evan Cornell '45 North Point Press, 1980. 291 pp. $12.50

There is no doubt who is the best writer to have attended Dartmouth. No doubt at all. That briefly attending member of the class of 1896 is also the best poet to have been born in America.

But second place? That's more complex and interesting. The strong contenders include Richard Eberhart '26, A. J. Liebling '24, and Joel Barlow, author of the Columbiad, who would have been class of 1778 if he had stayed to graduate. They also include a 56-year-old native of Kansas City named Evan Connell.

Connell established himself about 25 years ago with a fine collection of stories called TheAnatomy Lesson and a still finer novel called Mrs. Bridge. It was immediately apparent that the Middle West had a major new voice. Since then he has published ten more volumes, ranging from a book-length poem through numerous novels to last year's The WhiteLantern, a distinguished volume of essays. Here is a new book, another collection of stories, Connell's third. It will neither greatly help nor greatly hurt his reputation.

Nine of the 16 stories in Saint Augustine'sPigeon are reprints from the two earlier collections, and seven are new at least to book form. They are not necessarily newly written. What is somewhat troubling about the book is that on the whole the reprinted stories are better than the"new" ones. Several of these, in fact, strike me as quite old ones that were rightly excluded from earlier books, and a couple of others are so slight as barely to be stories at all. Call that the minus side.

The plus side is that Connell's best stories are really stunning and it is good to have them gathered here in one place. It is especially good to have the three stories called "Arcturus," "Otto and the Magi," and "Saint Augustine's Pigeon" printed one after the other.

All three of the stories are about a man named Muhlbach. He's originally from Kansas City, as his name suggests, but now he lives in New Jersey and works in New York. He's about 38. He has a 29-year-old wife named Joyce and two children.

In "Arcturus" there is a dinner party at the Muhlbach house. A small and tragic party with just two guests. The man is one Joyce Muhlbach had known (and loved) when they were both in college; the woman is a very young ballet dancer he has brought with him. The reader gradually becomes aware that Joyce is incurably ill, and that the male visitor is there because she has wanted very much to see him once more before she dies. He has come, and he has brought the little ballerina as protection. It is an astonishingly powerful story.

In the second story, Joyce has died. The story mainly centers on Muhlbach and his young son, though there is a subsidiary story line about the effort by some of his friends to fix him up with a good-looking dull divorcee named Eula Cun- ningham. (He prefers not to be fixed up just yet.)

In the third and finest of these stories, one might almost be in the world of Dante. Except, of course, that we are still around New York in the 20th century. It is a Saturday evening, and Muhlbach is home in his New Jersey suburb as a good insurance executive ought to be. One kid is in bed, the other working on an airplane model. The hired housekeeper has things under control. Muhlbach, who wants no part of Eula Cunningham, finds himself desperately eager to spend the night with a woman. Along about nine o'clock he takes the subway back into the city, feeling self-conscious. The rest of the story brilliantly describes his night-long failed search.

A book in which all the stories were as good as these three would be a major addition to American literature. Even a book in which these three appear is worth reading. And since they not only appear but make up a full half of the text, it is very much worth reading.

Noel Perrin teaches American literature at theCollege.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureDeath and Reunion: the loss of a twin

June 1981 By George L. Engel -

Cover Story

Cover StoryThe Long-Deferred Promise

June 1981 By Shelby Grantham -

Feature

FeatureRockefeller Center: the ideal of reflection and action

June 1981 By Donald McNemar -

Feature

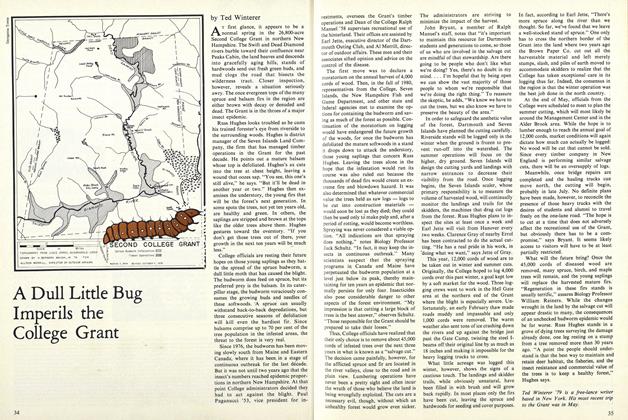

FeatureA Dull Little Bug Imperils the College Grant

June 1981 By Ted Winterer -

Article

ArticleDartmouth Authors

June 1981 -

Article

ArticleThe National Committee

June 1981

Books

-

Books

BooksTHE COLLECTION OF SOCIAL INSURANCE TAXES AND CONTRIBUTIONS BY MEANS OF STAMPS-ADHESIVE AND METER IMPRESSED.

May 1936 -

Books

BooksBriefly Noted

FEBRUARY 1967 -

Books

BooksUnmet Hope

MAY 1978 By DAVID DAWLEY '63 -

Books

BooksA Differentiation of Tongues

APRIL 1978 By GEO. WINCHESTER STONE JR. '30 -

Books

BooksREFLECTIONS ON THINGS AT HAND, THE NEO-CONFUCIAN ANTHOLOGY, COMPILED BY CHU HSI & LÜ-CHTEN.

NOVEMBER 1967 By T.S.K. SCOTT-CRAIG -

Books

BooksEDUCATION AND NATIONAL DEVELOPMENT IN MEXICO.

FEBRUARY 1968 By WAYNE G. BROEHL JR. '57h