Native American Studies

NATIVE AMERICAN STUDIES at Dartmouth began in the fall of 1972 as a modified department. In 1980, it was granted permanent program status by a unanimous vote of the faculty. Its content is the serious, intensive study of the cultures and histories of the indigenous inhabitants of both Americas, though the threemember faculty concentrates on North America. Its method is interdisciplinary.

The history of the program is a tale of phenomenal success, achieved in spite of many people's deep-seated doubts about adding to the curriculum something so hitherto unconsidered. "No, I wouldn't say it was easy," said Michael Dorris (Modoc), professor of anthropology and Native American studies, recalling the days when he set up the program that he still chairs. "It was challenging. And interesting. We had to carve something out of no space at all. I was an instructor then, I looked about 20 years old, and I had the job of chairing a program that everybody thought was beadwork and arts and crafts and a sop for Indian students, and we had to build that into something that had credibility."

Changing a college curriculum, as Presidents Dickey and Kemeny have both lamented, is like moving a cemetery. The work is long and slow and hard, and it stirs up profound emotions. The modern concept of interdisciplinary programs curricular coagulations of knowledge drawn from many separate departmental disciplines to form new and self-sufficient wholes unsettles people, especially when it is applied to politically "hot" minority groups. To many, both on campus and off, the movement away from what is seen as a solid unbreached core of traditional academic disciplines seems fraught with danger, with the risks of proliferation and degeneration.

Others, especially those who have been involved in one way or another with the College's Native American Studies Program, are more sanguine. They speak with reassuring certainty not only of the success of that particular program, but also of the educational value of the interdisciplinary approach and of the virtue of generating new fields of knowledge.

Historian Gregory Prince, associate dean of the faculty and associate provost at was director of summer programs in the early seventies, when he worked Closely with the College's nascent N.A.S. program. Prince, whose own doctorate was earned in Yale's interdisciplinary American studies program, pointed out the interdisciplinary nature of an earlier course of study such as moral philosophy, which included a broad range of subjects that only since the 18th century have been separated and specialized into disciplines. "I am not talking about a multi-disciplinary approach," Prince wanted to make clear, "but a real merging of different disciplines, a coming together to concentrate on a single problem. An interdisciplinary course is not one in which a historian comes in and lectures for three weeks and leaves, and then a political scientist, and then a scientist. To be interdisciplinary, faculty members have to engage with each other in developing material at every point in the course, which must address its subject matter constantly from the perspectives of several disciplines."

Professor of Anthropology Hoyt Alverson, who did much of the synthesizing work behind the original faculty recommendation to institute a program of Native American studies, feels that the fluctuation of the boundaries of knowledge is healthy and natural. He explained that sometimes, however, a lag occurs in the shifting of the boundaries, a lag during which knowledge arising - from the hybridization of traditional fields may not be accepted into any of the current disciplines. "Then," said Alverson, "you mahave to design a program in order to create a congenial atmosphere to promote working contact among disciplines that view each other with a certain amount of totemic suspicion." At the same time, according to Alverson, there is a definite need for priorities and limits in the institutionalization of burgeoning knowl- edge. "Given a finite set of resources, there is a number of programs beyond which a university shouldn't try seriously to offer more. I would be very surprised if Dartmouth developed a serious interest in teaching agriculture, but I would not deny that agriculture is a very legitimate field of study." He smiled. "There is nothing sacred about the institutional designation of a category of knowledge or intellectual activity and that's true of programs and departments."

Rayna Green (Cherokee), visiting professor of Native American studies, admitted that questions about curricular legitimacy and scholarly substance are "real and major," but she, too, feels that something like Native American studies is not, curricularly speaking, a new development. "It's not different from medieval studies or American studies, which were new in 1940, and at that point they were considered crazed and radical. After all, Harvard didn't teach American literature until the forties. Every time a new area is introduced it is seen and understood as a radical departure, but the process is neither new nor radical. Education has always chosen areas of study in order to illuminate the whole. It seems perfectly respectable even stuffy to me." She brooded a moment and then grinned. "If you really wanted to be radical, you would overturn the universities and let people do reading with one professor the way they do in Europe, and quit this collective behavior."

Michael Green, professor of history and Native American studies, who specialized as a graduate student in frontier American history, described a certain resistance among traditional historians to the crossdisciplinary, experimental approach to curriculum that began to develop on American campuses in the early seventies. The prevailing attitude was that minoritybased interdisciplinary courses were academically lousy fads, and Green recalled that before he came to Dartmouth he had never really examined that attitude, had, in fact, more or less accepted it himself. He was even somewhat reluctant to apply in 1976 for Dartmouth's advertised joint position in history and Native American studies. "There weren't many positions available, though, so I applied," he explained, "but mainly because Dartmouth's History Department has a good reputation. The idea of a joint appointment was scary. I was worried about the hazards of maintaining an identity in two departments and two communities, of trying to set up a pleasing human experience in two communities, and of juggling the chances of tenure in two departments."

Green also did not want to leave lowa to - come to New England, even though his mother was raised in Union Village, Vermont. He has become a thorough-going desert rat, he said, complaining that trees and mountains make him feel hemmed in. However, Dartmouth's Native American Studies Program turned out to be just as appealing as its History Department. "It didn't fit any of my stereotypes," said Green. "It wasn't highly political, or remedial, or academically sloppy, or designed solely for Native Americans. So I sacrificed the region for the academic climate." But he gave a sigh, just a little one, and added that he would happily drive the first truck moving Dartmouth College to the desert.

The program's newest faculty member, Andrew Wiget, who holds a joint appointment in English and Native American studies, sees himself similarly astraddle the boundary between the old and the new and is content (if sometimes a little harried) that way. For him, the basic difference between a program and a discipline is that a program springs from the real world in which a single person has many varied roles, whereas a discipline is useful because it abstracts and focuses attention on a single aspect of human experience. "Having moved in a discipline from the producer to the product," he explained, "we then turn and move in a program from the product back to the producer." He paused and shook his head. "I hate that. That's a lousy image. But that is the movement. And I think we need them both."

One of the great advantages of Dartmouth's N.A.S. program, according to Wiget, lies in the fact that it incorporates both, since all faculty appointments in it are by design shared appointments, half in a long-recognized discipline and half in the program. "In a sense, that allows us to institutionalize that movement between product and producer, back and forth. That dialogue is very useful, very constructive," he explained.

THOSE who are made uneasy by programs such as Native American studies sometimes allay their fears by regarding the programs as temporary measures, as stopgaps whose function is to beef up the traditional disciplines with, new knowledge and new perspectives. In this view, interdisciplinary programs (especially for unclear and probably suspect reasons those concerned with minority groups) are designed to self-destruct when their updating missions are fulfilled. President Kemeny himself articulated this idea in his 1975 five-year report: "The programs in black studies and Native American studies will be most successful if at the end of eight years the reason for their existence has vanished. They were created in recognition of the fact that existing departments historically have given an exclusively white orientation to subject offerings. As the orientation of courses in literature, history, politics, sociology, and anthropology fully recognize the contributions and special problems of black and Native Americans, we will no longer need the specialized programs."

Asked about this much-discussed statement, Kemeny smiled ruefully and replied, " Yes, well, I've just tried the same idea on the visiting committee on women's studies. I always get terrible flack on that statement. I can understand it, but what I had in mind was something very simple, namely that I don't want any of these courses to be out somewhere on the fringe of academia. If somebody wanted to learn about the history of Native Americans, I felt there should be a course in the History Department, and, most important, it wouldn't have to be a separate course, but would be in the normal sequence of courses — he or she would learn American history, not white American history, but American history."

Dorris's response to Kemeny's statement was to point out that while it was then (and still is) desirable that departments increase their course offerings and interests in the area of Native American studies, it was then (and still is) impossible to forecast in that prescriptivesounding way the future of the College's core N.A.S. program. Dorris's response stressed, too, that nothing in particular links Native American studies and black studies, or distinguishes only those two programs from Dartmouth's other interdisciplinary programs, such as urban studies, Asian studies, or comparative literature. He explained that one of the aims of all interdisciplinary programs not just those that deal with minority populations is to stimulate interest in and consciousness of the body of scholarly knowledge they represent on the part of the faculty as a whole and on the part of certain departments in particular. In Dorris's view, "Growth in the number of departmental course offerings dealing with Native American topics, and the continuation of a series of core courses in Native American studies per se, need not be mutually exclusive goals."

After worrying the self-destruct question for a few minutes, Professor of Public Affairs Frank Smallwood '5l (who helped shepherd N.A.S. into the curriculum) produced some political and historical insights: "I think you would want to keep a Native American studies, at least a core. It's not a discipline in the traditional sense, but it has its own body of knowledge that I don't think you are going to cover through individual departments. Maybe you could, I don't know. But when you work through the departments, you are dependent on their good will." Smallwood was worried, he said, about a neglect factor: "We go on to some new crisis that's the new fad. During the sixties and seventies equal opportunity was on the front burner, but you already see signs that people are getting tired of it. We get bored very easily. We want to go off and solve some other problem, not having solved the first one. I think it's important to have some central group here as a catalyst, pushing for quality in this area."

In some ways, history has justified Smallwood's fears. Smallwood was acting dean of the faculty at the time the N.A.S. program was proposed, and because he felt that the faculty had neglected to consider carefully the full responsibilities involved when it voted in the College's first, toohastily constructed black studies program in 1969, he pushed hard to get the faculty to acknowledge those responsibilities in the case of N.A.S. The faculty did formally acknowledge in connection with the adoption of the Native American Studies Program "an immediate need for the introduction of a Native American content" in other departments, and it pledged itself to work toward that end. But in the nine years since that mandate was articulated, it has been largely unfulfilled.

Dorris's report to the 1975 review committee contained eloquent statistics: "While many individual faculty and departments have demonstrated their good faith by serving on the N.A.S. Advisory Committee or by co-sponsoring events, it remains true that no new courses have been developed anywhere in the College specifically concerning Native Americans, only one existent course has been modified, and, to my knowledge, not a single Native American has been seriously considered, interviewed, or recruited to teach at Dartmouth outside the N.A.S. Program itself." The 1980 evaluation team found the situation just as disappointing: "The 1980 Review Committee has not discerned strong efforts on the part of the departments or of individual faculty members at Dartmouth to seek out guidance from the N.A.S. Program on how to incorporate Native American content into their courses and curricula."

Looking back from the security of permanent program status, Dorris in 1981 could be philosophical about the faculty's failure to meet its own charge: "I don't know that it was ever realistic. The school is so highly pressured in terms of tenure that it's asking the impossible to expect a junior professor to take time to learn a new area and teach it when he or she doesn't know whether it will be credited in the department. Senior professors are, well, into books and so forth everybody has his or her own primary commitment to a department and a specialty. I think it is our very presence here that has contributed what awareness there is on campus of things Native American and that has helped to infuse some material dealing with Native Americans into courses in which it probably would not have appeared had we not been here."

To the whole recently re-vexed question of whether Dartmouth's curriculum is "breaking down" because of programs such as Native American studies, Dorris responded, "This is an area study. I don't know that it has the same kind of theoretical core that a discipline has, but it has a field that can be covered in microcosm and brings together a lot of different disciplines and makes people think about things in a new way. We do not encourage students to major in Native American studies. We are not out to build an empire. I don't know what lots of Dartmouth students would do with a major in Native American studies. You can do a special major in it, as you can in anything, if you really put your mind to it. In the last nine years, we have had two students who did, in fact: One became the casting director of Barney Miller and the other is running an ecology ranch for high-school students in Wyoming. I don't know what, if anything, that says."

What is encouraged in Native American studies, according to Dorris, is the supplementation of another major. For a certificate in N.A.S., students have to meet all the requirements of the program, and they are encouraged to do an internship in a native community or research organization as well. "I think that makes a very marketable degree," said Dorris, "either for law or business, or for any of the professions, because it demonstrates a breadth as well as a depth in a particular culture area."

Faculty and students both pointed to two major gaps in Dartmouth's N.A.S. program languages and the arts. "A native language course every year, instead of every other year, would be good," explained Rayna Green. "We don't have nearly the capability we ought to have in the arts in general. Language, general culture, dance, music, art we don't have the faculty to cover those areas and we have to make do when we can with speakers." Green feels, too, that the N.A.S. program would benefit from more course work in modern issues, along the lines of the seminar on energy and natural resource development policy that she taught last term.

For the most part, however, people speak of the tremendous success of Dartmouth's Native American Studies Program. They give credit for it first to Dorris's adeptness as a teacher and a leader, and particularly to his unwavering insistence on the separation of the academic program of Native American studies and the support organization, Native American Programs, which handles counseling, cultural events (speakers, films, dinners, and powwows), tutoring referrals, work-study arrangements, and management of the Native American House, a social and culturalcen center. President Kemeny, describing the rocky early years of the College's modern involvement with Native Americans, admitted to having learned, among other lessons, the wisdom of this approach: "I did not think of the academic part at all in the beginning. What I was concerned about was admitting them and realizing that many of them would" come from very poor schools and would need support. In the beginning, we had everything all in one hodge-podge, and I'm sure that as long as the two things were mixed together, some significant number of faculty looked at the academic program as being somehow not quite a normal one. The separation was very, very important. Even today, too many people do not note the separation between the fact that we have a commitment to Native American students and the fact that we have an academic program at Dartmouth which is a highly respectable and strong academic program."

Another factor in the success of N.A.S., everyone agrees, is the extraordinarily strong presidential, trustee, and faculty support it has always enjoyed, support that has included vital "hard money" funding out of regularly budgeted College monies. (In addition, N.A.S. has always managed to secure sizable amounts of "soft" or grant money from such outside agencies as the Education Foundation of America, Aetna, and Polaroid, money that has often been budget-relieving.)

The ability of those at N.A.S. to lure well-known speakers to campus has impressed others. Gregory Prince recalled moments of controversy and tension among Native Americans across the country during the A.I.M. protests and Wounded Knee, for instance and said that all the people whose names he kept seeing in the newspapers he also kept seeing at Dartmouth. "I met almost every one of them," he said, "and they represented the entire political spectrum of the Native American community, all of the diversity that exists in all of the 150 or so differing Indian nations within the national Native American community. That has given our program a national flavor and an exposure to the complexities of Native American . communities, and it has helped in the crucial realization that we are not dealing with a single entity but with many diverse cultures and peoples."

RANDOM interviewing among some of the students enrolled in Native American studies courses produced further testimony to Dorris's teaching abilities and revealed an inspiring plurality of motives for enrolling. A French major started taking Native American studies courses "out of sheer interest," and a physicspsychology major out of a desire to learn something about the world of her partCherokee grandmother; one senior took his first N.A.S. course as a freshman because, as he put it, "I had heard this college was founded originally for Native Americans, for their progress in education, and I just wanted to know what was going on and why." Students, both native and non-native, were particularly enthusiastic about the program's internships, whether they had actually been on one or were just hoping to be, and several students whose schedules would not accommodate an undergraduate internship with N.A.S. expressed serious interest in doing one after graduation.

Dorris explained the N.A.S. internship program by recalling an incident from the early days: "One of the first years I was here, a group of kids who were very much back-to-the-earth types wanted to go off and help the Hopi harvest corn. I told them they would do that over my dead body. I told them our internships are set up so that people go out with our imprimatur only if they are requested and invited by the native community. The arrogance of people who, with all good intentions, would go without being invited to 'help' a people who have successfully harvested corn for over 4,000 years well, it's just a different approach. To be an intern with us, a student must take two N.A.S. courses, give us a resume, a transcript, and a statement of what she or he wants to do. We try to identify situations that need and would utilize their skills, and if the native people involved want the student, they write a letter of invitation back. Only then do we send an intern out. We try to match individual students with Indian organizations or programs or tribes so as to benefit both."

Among Dartmouth's Native American studies scholars themselves, faculty and students, exists also a collegiality that clearly contributes a great deal to the success of the enterprise. Each faculty member showed not only great respect for the others but also a genuine affection for them. As Wiget put it, "I came here for two reasons. One was the program's academic excellence, but the other was just as important. I liked the people I met in the program." Rayna Green felt the same way, adding, "As most Indians do, we also cross age barriers. There is a real relationship between faculty and students in Native American studies." Dorris described a relaxed and concerned community: "People come in and out as they like, and when there is any kind of trouble, or anybody is in distress, the entire constellation of people rallies around. There is a lot of affection, and it extends both to those who graduate and those who move on to other schools. A whole network of students who have been in this program maintain friendships among themselves and also with the people who are still here, taking a sort of avuncular role with them. It is one of the best parts of the program, and it extends not just to Indians but to non-Indians, too."

The students were outspokenly appreciative of the relationships they had developed with others in N.A.S. Anthropology major Roberta Joe '82 (Navajo) explained it best: "People are there when they say they are going to be, and they are always willing to help. I went to the University of New Mexico for the fall term, and I was really disappointed. I couldn't develop the kind of relationships with faculty and students that I have here. You would think N.A.S. would be really good at New Mexico, considering that there is a high native population there, but it was nothing compared to what we have here. People were never available, nobody knew where they were or when they would be back. The secretary would just say, 'No, he's not here.' Period. That's bad for students, for young people trying to learn, who need role models and guidance. A lot of faculty and staff have already established what they are doing with their lives, and they have a responsibility to the young people, who don't know yet. That's part of becoming friends with students, so you can help by directing them. Not so much molding them as enlightening them, so they aren't wandering around. That was important to me. People at N.A.S. said to me, 'You have this ability, or this natural talent. Try this.' I wouldn't go so far as to say they changed my life, but they kept me going, motivated me, and developed what I have."

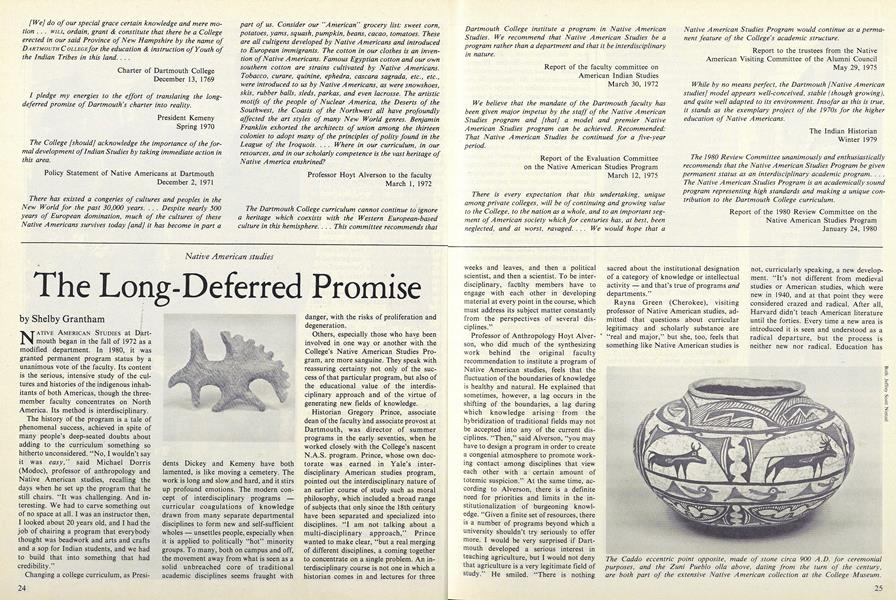

The Caddo eccentric point opposite, made of stone circa 900 A.D. for ceremonialpurposes, and the Zuni Pueblo olla above, dating from the turn of the century,are both part of the extensive Native American collection at the College Museum.

Yale-trained anthropologist Michael Dorrishas held Danforth, Wilson, and Guggenheim fellowships, and he recently declineda Fulbright lectureship in Leningrad.

Historian Michael Green became an ethnohistorian when he discovered he could notstudy U.S. policy toward the Creeks without learning something about Creek society.

A Navajo poem affirming life, the bond between all beings, and the inviolabilityof personal experience led Andrew Wiget past his traditional American literaturedegree to a study of Native American literature, the oral traditions in particular.

The College's Native American collectionincludes this magnificently beaded Chickasaw shoulder bag (Southeast, circa 1850).

Rayna Green, a former American Association for the Advancement of Scienceproject director, heads Dartmouth's newNative American Science Resource Center.

[We] do of our special grace certain knowledge and mere motion . . . WILL, ordain, grant & constitute that there be a Collegeerected in our said Province of New Hampshire by the name ofDARTMOUTH COLLEGE for the education & instruction of Youth ofthe Indian Tribes in this land. . . . Charter of Dartmouth College December 13, 1769 I pledge my energies to the effort of translating the longdeferred promise of Dartmouth's charter into reality. President Kemeny Spring 1970 The College [should] acknowledge the importance of the formal development of Indian Studies by taking immediate action inthis area. Policy Statement of Native Americans at Dartmouth December 2, 1971 There has existed a congeries of cultures arid peoples in theNew World for the past 30,000 years. . . . Despite nearly 500years of European domination, much of the cultures of theseNative Americans survives today [and] it has become in part apart of us. Consider our "American" grocery list: sweet corn,potatoes, yams, squash, pumpkin, beans, cacao, tomatoes. Theseare all cultigens developed by Native Americans and introducedto European immigrants. The cotton in our clothes is an invention of Native Americans. Famous Egyptian cotton and our ownsouthern cotton are strains cultivated by Native Americans.Tobacco, curare, quinine, ephedra, cascara sagrada, etc., etc.,were introduced to us by Native Americans, as were snowshoes,skis, rubber balls, sleds, parkas, and even lacrosse. The artisticmotifs of the people of Nuclear America, the Deserts of theSouthwest, the Coasts of the Northwest all have profoundlyaffected the art styles of many New World genres. BenjaminFranklin exhorted the architects of union among the thirteencolonies to adopt many of the principles of polity found in theLeague of the Iroquois. . . . Where in our curriculum, in ourresources, and in our scholarly competence is the vast heritage ofNative America enshrined? Professor Hoyt Alverson to the faculty March 1, 1972 The Dartmouth College curriculum cannot continue to ignorea heritage which coexists with the Western European-basedculture in this hemisphere. . . . This committee recommends thatDartmouth College institute a program in Native AmericanStudies. We recommend that Native American Studies be aprogram rather than a department and that it be interdisciplinaryin nature. Report of the faculty committee on American Indian Studies March 30, 1972 We believe that the mandate of the Dartmouth faculty hasbeen given major impetus by the staff of the Native AmericanStudies program and [that] a model and premier NativeAmerican Studies program can be achieved. Recommended:That Native American Studies be continued for a five-yearperiod. Report of the Evaluation Committee on the Native American Studies Program March 12, 1975 There is every expectation that this undertaking, uniqueamong private colleges, will be of continuing and growing valueto the College, to the nation as a whole, and to an important segment of American society which for centuries has, at best, beenneglected, and at worst, ravaged. . . . We would hope that aNative American Studies Program would continue as a permanent feature of the College's academic structure. Report to the trustees from the Native American Visiting Committee of the Alumni Council May 29, 1975 While by no means perfect, the Dartmouth [Native Americanstudies] model appears well-conceived, stable (though growing),and quite well adapted to its environment. Insofar as this is true,it stands as the exemplary project of the 1970s for the highereducation of Native Americans. The Indian Historian Winter 1979 The 1980 Review Committee unanimously and enthusiasticallyrecommends that the Native American Studies Program be givenpermanent status as an interdisciplinary academic program. . . .The Native American Studies Program is an academically soundprogram representing high standards and making a unique contribution to the Dartmouth College curriculum. Report of the 1980 Review Committee on the Native American Studies Program January 24, 1980

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureDeath and Reunion: the loss of a twin

June 1981 By George L. Engel -

Feature

FeatureRockefeller Center: the ideal of reflection and action

June 1981 By Donald McNemar -

Feature

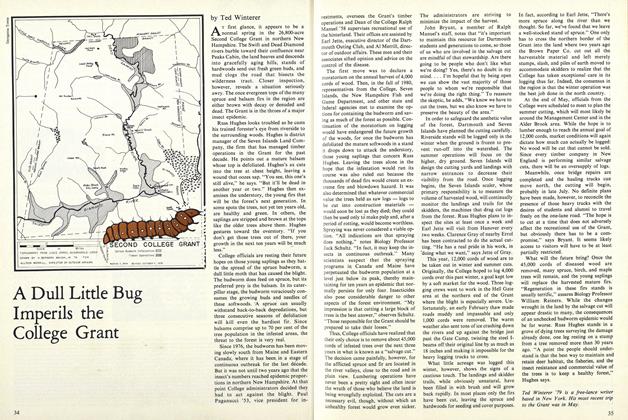

FeatureA Dull Little Bug Imperils the College Grant

June 1981 By Ted Winterer -

Article

ArticleDartmouth Authors

June 1981 -

Article

ArticleThe National Committee

June 1981 -

Books

BooksWhat If?

June 1981 By R. H. R.

Shelby Grantham

-

Feature

FeatureWomen at the Top (almost)

May 1977 By SHELBY GRANTHAM -

Feature

FeatureThe Wooden Shoe: A Commune

May 1979 By Shelby Grantham -

Feature

FeatureWindows on a World

DECEMBER 1982 By Shelby Grantham -

Cover Story

Cover StoryConsortium

APRIL 1984 By Shelby Grantham -

Cover Story

Cover StoryThe Montgomery Endowment Finds a Home

SEPTEMBER 1984 By Shelby Grantham -

Feature

FeatureBONFIRE!

OCTOBER • 1986 By Shelby Grantham

Features

-

Feature

FeatureMorton, Kilmarx Elected Charter Trustees

MAY 1972 -

Feature

FeatureDONALD PEASE

Sept/Oct 2010 -

Cover Story

Cover StoryREVISED “MEN OF DARTMOUTH” POEM

MARCH | APRIL 2014 -

Feature

FeatureBuilding for Today—and 1969

February 1951 By PROF. JOHN P. AMSDEN '20 -

Feature

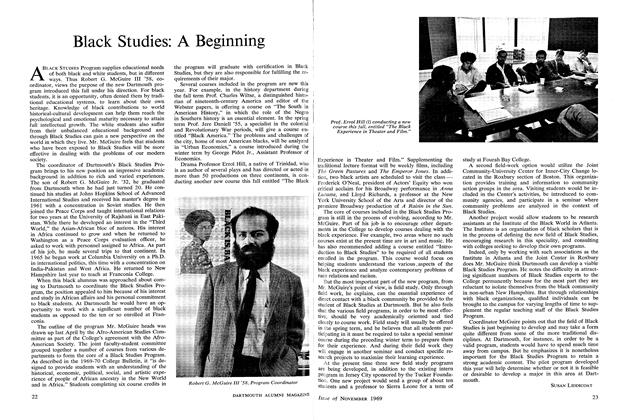

FeatureBlack Studies: A Beginning

NOVEMBER 1969 By SUSAN LIDDICOAT