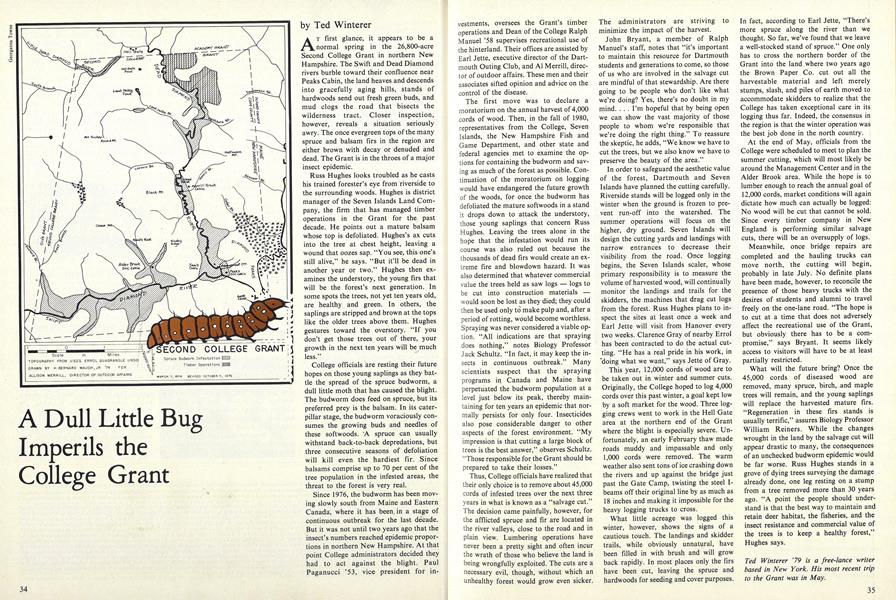

AT first glance, it appears to be a normal spring in the 26,800-acre Second College Grant in northern New Hampshire. The Swift and Dead Diamond rivers burble toward their confluence near Peaks Cabin, the land heaves and descends into gracefully aging hills, stands of hardwoods send out fresh green buds, and mud clogs the road that bisects the wilderness tract. Closer inspection, however, reveals a situation seriously awry. The once evergreen tops of the many spruce and balsam firs in the region are either brown with decay or denuded and dead. The Grant is in the throes of a major insect epidemic.

Russ Hughes looks troubled as he casts his trained forester's eye from riverside to the surrounding woods. Hughes is district manager of the Seven Islands Land Company, the firm that has managed timber operations in the Grant for the past decade. He points out a mature balsam whose top is defoliated. Hughes's ax cuts into the tree at chest height, leaving a wound that oozes sap. "You see, this one's still alive," he says. "But it'll be dead in another year or two." Hughes then examines the understory, the young firs that will be the forest's next generation. In some spots the trees, not yet ten years old, are healthy and green. In others, the saplings are stripped and brown at the tops like the older trees above them. Hughes gestures toward the overstory. "If you don't get those trees out of there, your growth in the next ten years will be much less."

College officials are resting their future hopes on those young saplings as they battle the spread of the spruce budworm, a dull little moth that has caused the blight. The budworm does feed on spruce, but its preferred prey is the balsam. In its caterpillar stage, the budworm voraciously consumes the growing buds and needles of these softwoods. 'A spruce can usually withstand back-to-back depredations, but three consecutive seasons of defoliation will kill even the hardiest fir. Since balsams comprise up to 70 per cent of the tree population in the infested areas, the threat to the forest is very real.

Since 1976, the budworm has been moving slowly south from Maine and Eastern Canada, where it has been, in a stage of continuous outbreak for the last decade. But it was not until two years ago that the insect's numbers reached epidemic proportions in northern New Hampshire. At that point College administrators decided they had to act against the blight. Paul Paganucci '53, vice president for in vestments, oversees the Grant's timber operations and Dean of the College Ralph Manuel 'SB supervises recreational use of the hinterland. Their offices are assisted by Earl Jette, executive director of the Dartmouth Outing Club, and Al Merrill, director of outdoor affairs. These men and their associates sifted opinion and advice on the control of the disease.

The first move was to declare a moratorium on the annual harvest of 4,000 cords of wood. Then, in the fall of 1980, representatives from the College, Seven Islands, the New Hampshire Fish and Game Department, and other state and federal agencies met to examine the options for containing the budworm and saving as much of the forest as possible. Continuation of the moratorium on logging would have endangered the future growth of the woods, for once the budworm has defoliated the mature softwoods in a stand it drops down to attack the understory, those young saplings that concern Russ Hughes. Leaving the trees alone in the hope that the infestation would run its course was also ruled out because the thousands of dead firs would create an extreme fire and blowdown hazard. It was also determined that whatever commercial value the trees held as saw logs logs to be cut into construction materials

would soon be lost as they died; they could then be used only to make pulp and, after a period of rotting, would become worthless. Spraying was never considered a viable option. "All indications are that spraying does nothing," notes Biology Professor Jack Schultz. "In fact, it may keep the insects in continuous outbreak." Many scientists suspect that the spraying programs in Canada and Maine have perpetuated the budworm population at a level just below its peak, thereby maintaining for ten years an epidemic that normally persists for only four. Insecticides also pose considerable danger to other aspects of the forest environment. "My impression is that cutting a large block of trees is the best answer," observes Schultz. "Those responsible for the Grant should be prepared to take their losses."

Thus, College officials have realized that their only choice is to remove about 45,000 cords of infested trees over the next three years in what is known as a "salvage cut." The decision came painfully, however, for the afflicted spruce and fir are located in the river valleys, close to the road and in plain view. Lumbering operations have never been a pretty sight and often incur the wrath of those who believe the land is being wrongfully exploited. The cuts are a necessary evil, though, without which an unhealthy forest would grow even sicker. The administrators are striving to minimize the impact of the harvest.

John Bryant, a member of Ralph Manuel's staff, notes that "it's important to maintain this resource for Dartmouth students and generations to come, so those of us who are involved in the salvage cut are mindful of that stewardship. Are there going to be people who don't like what we're doing? Yes, there's no doubt in my mind. ... I'm hopeful that by being open we can show the vast majority of those people to whom we're responsible that we're doing the right thing." To reassure the skeptic, he adds, "We know we have to cut the trees, but we also know we have to preserve the beauty of the area."

In order to safeguard the aesthetic value of the forest, Dartmouth and Seven Islands have planned the cutting carefully. Riverside stands will be logged only in the winter when the ground is frozen to prevent run-off into the watershed. The summer operations will focus on the higher, dry ground. Seven Islands will design the cutting yards and landings with narrow entrances to decrease their visibility from the road. Once logging begins, the Seven Islands scaler, whose primary responsibility is to measure the volume of harvested wood, will continually monitor the landings and trails for the skidders, the machines that drag cut logs from the forest. Russ Hughes plans to inspect the sites at least once a week and Earl Jette will visit from Hanover every two weeks. Clarence Gray of nearby Errol has been contracted to do the actual cutting. "He has a real pride in his work, in "doing what we want," says Jette of Gray.

This year, 12,000 cords of wood are to be taken out in winter and summer cuts. Originally, the College hoped to log 4,000 cords over this past winter, a goal kept low by a soft market for the wood. Three logging crews went to work in the Hell Gate area at the northern end of the Grant where the blight is especially severe. Unfortunately, an early February thaw made roads muddy and impassable and only 1,000 cords were removed. The warm weather also sent tons of ice crashing down the rivers and up against the bridge just past the Gate Camp, twisting the steel Ibeams off their original line by as much as 18 inches and making it impossible for the heavy logging trucks to cross.

What little acreage was logged this winter, however, shows the signs of a cautious touch. The landings and skidder trails, while obviously unnatural, have been filled in with brush and will grow back rapidly. In most places only the firs have been cut, leaving the spruce and hardwoods for seeding and cover purposes. In fact, according to Earl Jette, "There's more spruce along the river than we thought. So far, we've found that we leave a well-stocked stand of spruce." One only has to cross the northern border of the Grant into the land where two years ago the Brown Paper Co. cut out all the harvestable material and left merely stumps, slash, and piles of earth moved to accommodate skidders to realize that the College has taken exceptional care in its logging thus far. Indeed, the consensus in the region is that the winter operation was the best job done in the north country.

At the end of May, officials from the College were scheduled to meet to plan the summer cutting, which will most likely be around the Management Center and in the Alder Brook area. While the hope is to lumber enough to reach the annual goal of 12,000 cords, market conditions will again dictate how much can actually be logged: No wood will be cut that cannot be sold. Since every timber company in New England is performing similar salvage cuts, there will be an oversupply of logs.

Meanwhile, once bridge repairs are completed and the hauling trucks can move north, the cutting will begin, probably in late July. No definite plans have been made, however, to reconcile the presence of those heavy trucks with the desires of students and alumni to travel freely on the one-lane road. "The hope is to cut at a time that does not adversely affect the recreational use of the Grant, but obviously there has to be a compromise," says Bryant. It seems likely access to visitors will have to be at least partially restricted.

What will the future bring? Once the 45,000 cords of diseased wood are removed, many spruce, birch, and maple trees will remain, and the young saplings will replace the harvested mature firs. "Regeneration in these firs stands is usually terrific," assures Biology Professor William Reiners. While the changes wrought in the land by the salvage cut will appear drastic to many, the consequences of an unchecked budworm epidemic would be far worse. Russ Hughes stands in a grove of dying trees surveying the damage already done, one leg resting on a stump from a tree removed more than 30 years ago. "A point the people should understand is that the best way to maintain and retain deer habitat, the fisheries, and the insect resistance and commercial value of the trees is to keep a healthy forest," Hughes says.

Ted Winterer '79 is a free-lance writerbased in New York. His most recent tripto the Grant was in May.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureDeath and Reunion: the loss of a twin

June 1981 By George L. Engel -

Cover Story

Cover StoryThe Long-Deferred Promise

June 1981 By Shelby Grantham -

Feature

FeatureRockefeller Center: the ideal of reflection and action

June 1981 By Donald McNemar -

Article

ArticleDartmouth Authors

June 1981 -

Article

ArticleThe National Committee

June 1981 -

Books

BooksWhat If?

June 1981 By R. H. R.

Features

-

Feature

FeatureMorton, Kilmarx Elected Charter Trustees

MAY 1972 -

Feature

FeatureMcLaughry Closes 14-Year Regime As Dartmouth's Head Football Coach

January 1955 By CLIFF JORDAN '45 -

Cover Story

Cover StoryCAN WE TALK?

MAY 1989 By Jay Heinrichs -

Feature

FeatureThe Fifty-Year Address

July 1958 By LAURIS G. TREADWAY '08 -

Feature

FeatureAlumni News

July/Aug 2013 By Mark Brosseau ’98, Mark Brosseau ’98 -

Feature

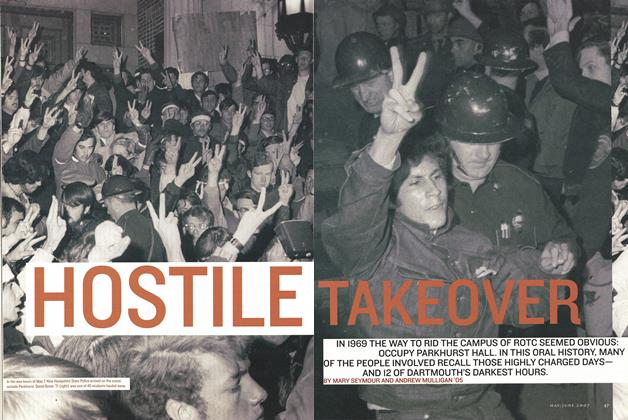

FeatureHostile Takeover

May/June 2007 By MARY SEYMOUR AND ANDREW MULLIGAN ’05