Since 1973, more than 265 women's studies programs have been established at American colleges and universities. Dartmouth became one of this number in May of 1978, when the faculty by a vote of 138 to 3 formally approved what would be the first women's studies program in the Ivy League. The moving force behind this action was a group of eight faculty women who drafted a formal proposal for the program and who later continued to push the idea among their colleagues. Although a smattering of women's studies courses were already being offered by a few departments, it wasn't until the fall of 1979 that Dartmouth was able to offer its first introductory survey course, Women's Studies 1.

Like the nine other academic programs at Dartmouth (such as Environmental Studies, Afro-American Studies, and Comparative Literature), Women's Studies is interdisciplinary. The program offers seven courses taught by teams, usually made up of one professor from the humanities and one from the social sciences. Moreover, cross-listed with Women's Studies are 16 courses from the various disciplines, among them Comparative Literature 56, "Women in Myth: Medea, Antigone, Electra"; Greek and Roman Studies 9, "Women in Classical Literature: Origins of the Western Attitude Towards Women"; and Religion ligion 54, "Sexuality, Society, and Religion."

As an academic program rather than a department, Dartmouth Women's Studies does not offer a major (although students can petition for a special major). Students can obtain a certificate in Women's Studies or do a modified major combining Women's Studies with another field such as history or English. For both the certificate and the modified major, a student must take six Women's Studies courses.

According to its brochure, Dartmouth Women's Studies "has emerged because traditional academic disciplines have failed to take account of, analyze, or incorporate into their theory and practice the actual experience and role of women." The brochure points out, however, that "Women's Studies is more than adding female figures to a traditional course." In contrast to what one feminist scholar has called the "add-women-andstir" method of incorporating women into the existing academic traditions, Dartmouth Women's Studies "seeks to examine academic traditions themselves."

Except when Women's Studies 1 was first offered back in 1979, the courses have not generally packed in big crowds. Although the number of students interested enough to complete requirements for the certificate have been increasing, overall enrollments have declined. Anne Brooks, who runs the Women's Studies Program office in Carpenter Hall, attributes this in part to pre-professionalism and peer pressure. "Taking Women's Studies places a great burden on the student," she says. "First, there's this idea that Women's Studies isn't serious and won't help you get into business school or law school. Then there's the problem of whether, if you take Women's Studies, people will ask, 'Oh, does that mean you're into women's lib?' There's a lot of peer pressure not to take that kind of risk." Discussing one of the relatively few male students to have achieved a certificate in Women's Studies, Brooks remarks, "His fraternity brothers kidded him a lot."

Risk aside, Women's Studies seems to have a large impact on some students. "Especially in Women's Studies 1, things pop open for students," Brooks says. "Suddenly, they start seeing things they had never noticed before, and then they take this new perspective into their other courses. . . . One woman went and asked her English professor how come in his course in Victorian literature there was not one woman author in the syllabus. It wasn't a question he really wanted to hear."

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureWHY STUDY WOMEN?

October 1982 By Mary Ellen Donovan -

Feature

FeatureHome, Home on the Plain

October 1982 By Jeffrey Boffa -

Feature

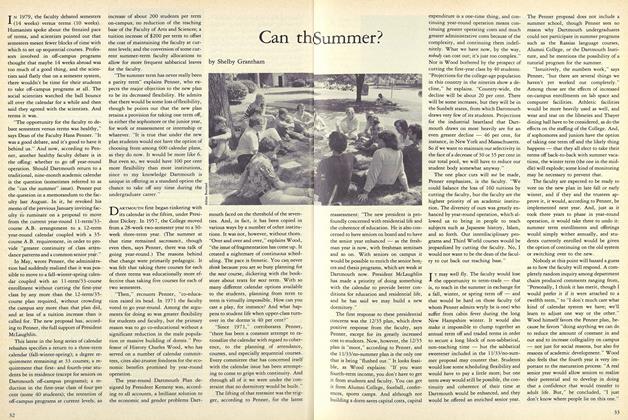

FeatureCan the Summer?

October 1982 By Shelby Grantham -

Sports

SportsAn Irish Connection and a Quaker Shutout

October 1982 By Brad Hills '65 -

Class Notes

Class Notes1982

October 1982 By John King -

Article

ArticleSexagenarian Hiker Travels Light on the Appalachian Trail

October 1982 By D.C.G

Article

-

Article

ArticleTENTATIVE PROGRAM OF THE SECRETARIES' MEETING MARCH 14 AND 15

-

Article

ArticleRhodes Scholar

JANUARY 1932 -

Article

Article"Key-Hole Man"

October 1942 -

Article

ArticlePresident Wright Honors "Chick"

MARCH 1999 -

Article

ArticleBob Blackman: Tackling Retirement in Hilton Head

SEPTEMBER 1984 By Mary Ross -

Article

ArticleCOMMENCEMENT 1922

August, 1922 By PHILIP S. MARDEN '94