IN 1979, the faculty debated semesters (14 weeks) versus terms (10 weeks). Humanists spoke about the frenzied pace of terms, and scientists pointed out that semesters meant fewer blocks of time with which to set up sequential courses. Professors involved in off-campus programs thought that maybe 14 weeks abroad was too much of a good thing, and the scientists said flatly that on a semester system, there wouldn't be time for their students to take off-campus programs at all. The social scientists watched the ball bounce all over the calendar for a while and then said they agreed with the scientists. And terms it was.

"The opportunity for the faculty to debate semesters versus terms was healthy," says Dean of the Faculty Hans Penner. "It was a good debate, and it's good to have it behind us." And now, according to Penner, another healthy faculty debate is in the offing: whether to go off year-round operation. Should Dartmouth return to a traditional, nine-month academic calendar is the question (sometimes referred to as the "can the summer" issue). Penner put the question in a memorandum to the faculty last August. In it, he revoked his memo of the previous January inviting faculty to ruminate on a proposal to move from the current year-round 11-term/33course A.B. arrangement to a 12-term year-round calendar coupled with a 35course A.B. requirement, in order to provide "greater continuity of class attendance patterns and a common senior year."

In May, wrote Penner, the administration had suddenly realized that it was possible to move to a fall-winter-spring calendar coupled with an 11-term/33-course enrollment without cutting the first-year class by any more than the 12-term/3 5-course plan required, without crowding the campus any more than that plan did, and at less of a tuition increase than it called for. The new proposal has, according to Penner, the full support of President McLaughlin.

This latest in the long series of calendar rehashes specifies a return to a three-term calendar (fall-winter-spring); a degree requirement remaining at 33 courses; a requirement that first- and fourth-year students be in residence (except for seniors on Dartmouth off-campus programs); a reduction in the first-year class of four per cent (some 40 students); the retention of off-campus programs at current levels; an increase of about 200 students per term on-campus; no reduction of the teaching base of the Faculty of Arts and Sciences; a tuition increase of $200 per term to offsethe cost of maintaining the faculty at current levels; and the conversion of some current summer-term faculty allocations to allow for more frequent sabbatical leaves for the faculty.

"The summer term has never really been a parity term" explains Penner, who expects the major objection to the new plan to be its decreased flexibility. He admits that there would be some loss offlexibility, though he points out that the new plan retains a provision for taking one term off, in either the sophomore or the junior year, for work or reassessment or internship or whatever. "It is true that under the new plan students would not have the option of choosing from among 600 calendar plans, as they do now. It would be more like 6. But even so, we would have 100 per cent more flexibility than most institutions, since to my knowledge Dartmouth is unique in offering as a standard option the chance to take off any time during the undergraduate career."

Dartmouth first began tinkering with its calendar in the fifties, under President Dickey. In 1957, the College moved from a 28-week two-semester year to a 30week three-term year. (The summer at that time remained sacrosanct, though even then, says Penner, there was talk of going year-round.) The reasons behind that change were primarily pedagogic. It was felt that taking three courses for each of three terms was educationally more effective than taking five courses for each of two semesters.

"Then," recounts Penner, "co-education raised its head. In 1971 the faculty voted to go year-round. Among the arguments for doing so was greater flexibility for students and faculty, but the primary reason was to go co-educational without a significant reduction in the male population or massive building of dorms." Professor of History Charles Wood, who has served on a number of calendar committees, cites also trustee fondness for the economic benefits promised by year-round operation.

The year-round Dartmouth Plan designed by President Kemeny was, according to all accounts, a brilliant solution to the economic and gender problems Dartmouth faced on the threshold of the seventies. And, in fact, it has been copied in various ways by a number of other institutions. It was not, however, without thorn. "Over and over and over," explains Wood, "the issue of fragmentation has come up. It created a nightmare of continuous scheduling. The pace is frenetic. You can never think because you are so busy planning for the next course, dickering with the bookstore about texts for next term. With so many different calendar options available to the students, planning from term to term is virtually impossible. How can you cast a play, for instance? And what happens to student life when upper-class turnover in the dorms'is 40 per cent?"

"Since 1971," corroborates Penner, "there has been a constant attempt to rationalize the calendar with regard to coherence, to the planning of attendance, courses, and especially sequential courses. Every committee that has concerned itself with the calendar issue has been attempting to come to grips with continuity. And through all of it we were under the constraint that no dormitory would be built."

The lifting of that restraint was the trigger, according to Penner, for the latest reassessment: "The new president is profoundly concerned with residential life and the coherence of education. He is also concerned to have seniors on board and to have the senior year enhanced as the freshman year is now, with freshman seminars and so on. With seniors on campus it would be possible to enrich the senior honors and thesis programs, which are weak at Dartmouth now. President McLaughlin has made a priority of doing something with the calendar to provide better conditions for education and residential life, and he has said we may build a new dormitory."

The first response to these presidential concerns was the 12/35 plan, which drew positive response from the faculty, says Penner, except for its greatly increased cost to students. Now, however, the 12/35 plan is "moot," according to Penner, and the 11/33/ no-summer plan is the only one that is being "flushed out." It looks feasible, as Wood explains: "If you want fourth-term income, you don't have to get it from students and faculty. You can get it from Alumni College, football, conferences, sports camps. And although not building a dorm saves capital costs, capital expenditure is a one-time thing, and continuing year-round operation means continuing greater operating costs and much greater administrative costs because of the complexity, and continuing them indefinitely. What we have now, by the way, nobody can cost out; it's just too complex." Nor is Wood bothered by the prospect of cutting the first-year class by 40 students: "Projections for the college-age population in this country in the nineties show a decline," he explains. "Country-wide, the decline will be about 20 per cent. There will be some increases, but they will be in the Sunbelt states, from which Dartmouth draws very few of its students. Projections for the industrial heartland that Dartmouth draws on most heavily are for an even greater decline 46 per cent, for instance, in New York and Massachusetts. So if we want to maintain our selectivity in the face of a decrease of 30 or 35 per cent in our total pool, we will have to reduce our student body somewhat anyway."

The one place cuts will not be made, Penner emphasizes, is the faculty. "We could balance the loss of 160 tuitions by cutting the faculty, but the faculty are the highest priority of an academic institution. The diversity of ours was greatly enhanced by year-round operation, which allowed us to bring in people to teach subjects such as Japanese history, Islam, and so forth. Our interdisciplinary programs and Third World courses would be jeopardized by cutting the faculty. No, I would not want to be the dean of the faculty to cut back our teaching base."

IT may well fly. The faculty would lose the opportunity to term-trade that is, to teach in the summer in exchange for a fall, winter, or spring term off and that would be hard on those faculty (of whom Penner admits wryly he is one) who suffer from cabin fever during the long New Hampshire winter. It would also make it impossible to clump together an annual term off and traded terms in order to secure a long block of non-sabbatical, non-teaching time but the sabbatical sweetener included in the 11/33/ no-summer proposal may counter that. Students would lose some scheduling flexibility and would have to pay a little more; but one term away would still be possible, the continuity and coherence of their time at Dartmouth would be enhanced, and they would be offered an enriched senior year. The Penner proposal does not include a summer school, though Penner sees no reason why Dartmouth undergraduates could not participate in summer programs such as the Rassias language courses, Alumni College, or the Dartmouth Institute, and he mentions the possibility of a tutorial program for the summer.

"Intuitively, the numbers work," says Penner, "but there are several things we haven't yet worked out completely." Among those are the effects of increased on-campus enrollments on lab space and computer facilities. Athletic facilities would be more heavily used as well, and wear and tear on the libraries and Thayer dining hall have to be considered, as do the effects on the staffing of the College. And, if sophomores and juniors have the option of taking one term off and the likely thing happens that they all elect to take their terms off back-to-back with summer vacations, the winter term (the one in the middle) will explode; some kind of monitoring may be necessary to prevent that.

The faculty are expected to be ready to vote on the new plan in late fall or early winter, and if they and the trustees approve it, it would, according to Penner, be implemented next year. And, just as it took three years to phase in year-round operation, it would take three to undo it: summer term enrollments and offerings would simply wither annually, and students currently enrolled would be given the option of continuing on the old system or switching over to the new.

Nobody at this point will hazard a guess as to how the faculty will respond. A completely random inquiry among department chairs produced comments ranging from, "Personally, I think it has merit, though I would prefer it if it were attached to a twelfth term," to "I don't much care what kind of calendar system we have; we'll learn to adjust one way or the other." Wood himself favors the Penner plan, because he favors "doing anything we can do to reduce the amount of constant in and out and to increase collegiality on campus not just for social reasons, but also for reasons of academic development." Wood also feels that the fourth year is very important to the maturation process: "A real senior year would allow seniors to realize their potential and to develop in doing that a confidence that would transfer to adult life. But," he concluded, "I just don't know where people lie on this one."

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureWHY STUDY WOMEN?

October 1982 By Mary Ellen Donovan -

Feature

FeatureHome, Home on the Plain

October 1982 By Jeffrey Boffa -

Sports

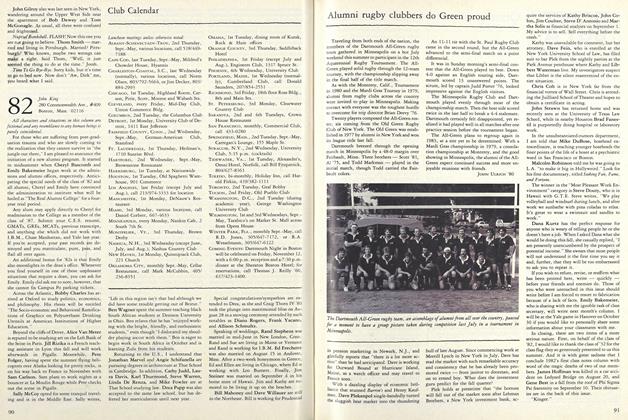

SportsAn Irish Connection and a Quaker Shutout

October 1982 By Brad Hills '65 -

Class Notes

Class Notes1982

October 1982 By John King -

Article

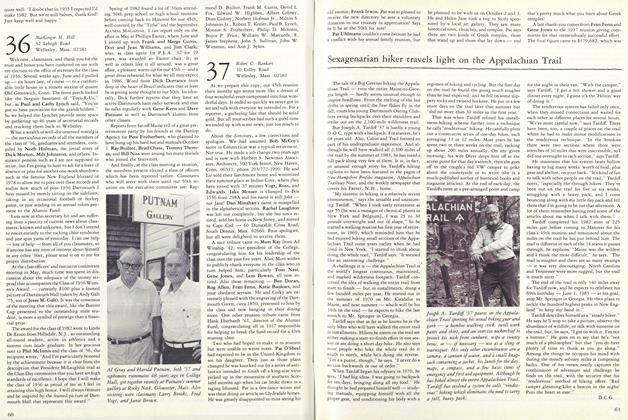

ArticleSexagenarian Hiker Travels Light on the Appalachian Trail

October 1982 By D.C.G -

Class Notes

Class Notes1945

October 1982 By Austin B. Wason

Shelby Grantham

-

Feature

FeatureJohnny can't write? Who cares?

January 1977 By Shelby Grantham -

Feature

FeatureFirst Five Months

DECEMBER 1981 By Shelby Grantham -

Feature

FeatureWindows on a World

DECEMBER 1982 By Shelby Grantham -

Feature

FeatureHigh Tech Crisis

JUNE 1983 By Shelby Grantham -

Feature

FeatureThe Attraction of Peanuts

JUNE/JULY 1984 By Shelby Grantham -

Feature

FeatureZen and the Art of Corporate Maintenance

JANUARY/FEBRUARY 1985 By Shelby Grantham

Features

-

Feature

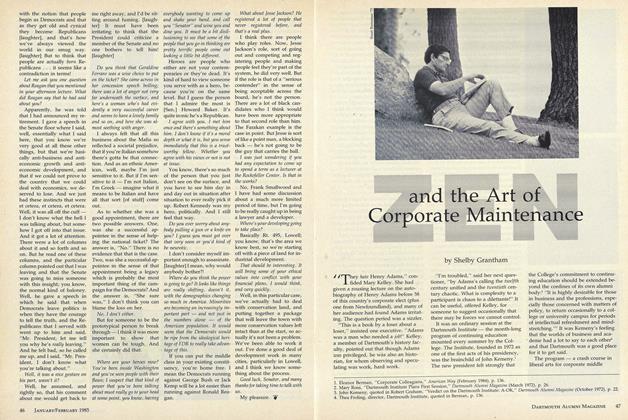

FeaturePhysical Facilities

April 1975 -

Feature

FeatureRUSSELL RICKFORD

Sept/Oct 2010 -

Feature

FeatureClass Notes

SEPTEMBER | OCTOBER 2014 By DARTMOUTH COLLEGE LIBRARY -

Feature

FeatureSubmariner

OCTOBER 1981 By M. B. R -

Cover Story

Cover StoryWell-Earned Minus

MARCH 1995 By William C. Sadd '62 -

Feature

FeatureToday: Views of an Embattled Oilman

April 1974 By WILLIAM K.TELL JR.