The California Supreme Court recently ruled that a statute proscribing violence "to achieve social or political goals" was void for vagueness. Professor Bishop's first paragraph implies endorsement of that ruling. As he explains, though, to define terrorism precisely is hardly a main goal.

The Irish do indeed exemplify problems of "control." I did not know until I read the Bishop article that no American contributing to the I.R.A. gives support to the Northern Ireland Civil Rights Association: I have, however, worked with Americans such as Hurst Hannum, who for four years following graduation from law school assisted that association and related groups and also represented Irish clients in submissions to the European Human Rights Commission and similar United Nations bodies. I.R.A. terrorism could be controlled if the British and U.S.

governments would support, not constantly oppose, those kinds of activities.

Our crusade against terrorism will lack integrity if we pretend that "governmental terrorism, such as that practiced ... by Libya and Iran" (and, demonstrably on occasion, by the U.S. and its allies) is separable. Not all "such governments have only contempt for international law." Many fear both censure and stronger sanctions imposable by the U.N., N.A.T.0., the Organization of African Unity, the Red Cross, and other international organizations. By no means, I believe, is "the problem of controlling terrorist violence . . . largely confined to democracies whose citizens have civil rights." That would exclude most of the world's governments, including many that we and our allies often have persuaded to join our ranks in confronting threats to shared interests.

Korematsu v. United States ranks with the Dred Scott, separate-but-equal, and other famed decisions that many observers contend are discredited. Yet by citing Korematsu Professor Bishop reminds us that even juridical issues can complicate terrorism controls.

Justice California Supreme Court

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureWhat keeps them going? A 'Mystic Glue' Perhaps

May 1982 By Dana Cook Grossman -

Feature

FeatureTerrorism and the Niceties of Justice

May 1982 By Joseph W. Bishop Jr. -

Feature

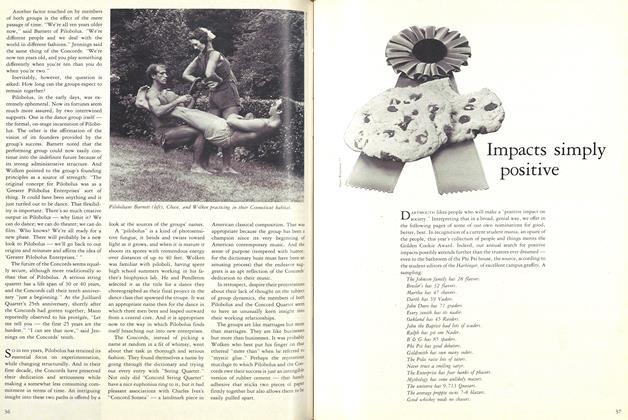

FeatureImpacts simply positive

May 1982 -

Article

ArticleIn the Wide, Wide World

May 1982 By Peter Smith -

Class Notes

Class Notes1964

May 1982 By Alexander D. Varkas Jr. -

Class Notes

Class Notes1954

May 1982 By John L. Gillespie

Article

-

Article

ArticleEDITORIAL TRIBUTE

April 1934 -

Article

ArticleMedical School Plans

November 1957 -

Article

ArticleGolden Book Returns

FEBRUARY 1964 -

Article

ArticleHooked on Toys

JANUARY/FEBRUARY 1984 By Peter Smith -

Article

ArticleDartmouth's Intellectual Life

APRIL 1930 By Prof. Charles J. Lyon -

Article

ArticleHeavy Metal Grant

September 1995 By Robert H. Nutt '49