is Professor Just. He properly belongs to an institution like the Rockefeller Institute, and he was the most logical candidate to take the place of Jacques Loeb when he died, but the Rockefeller Foundation, spending millions of dollars to combat disease internationally, couldn't summon enough courage to solve an interracial problem."

by Shelby Grantham

IN 1929, the administration of Brown University found Professor E. E. Just "quite ideal except for his race." He was not invited to join the faculty. In 1931, the University of Pennsylvania withstood the combined onslaught of philanthropist Julius Rosenwald, zoologist Frank Lillie, and three other eminent biologists in Just's behalf, to a similar end.

It was the same everywhere in white academia. So, at a time when Uncle Tom still held sway in the black colleges of this country, Ernest Everett Just '07, internationally-acclaimed embryologist, remained at the head of the zoology department of Howard University in Washington, D.C. There he struggled endlessly with an administration unsympathetic toward research.

For years, Howard made heavy teaching and administrative demands on Just. At one point he was put in charge of study programs for 500 premedical students. When finally he secured some research support from the Rosenwald Fund, the university's administrators set him the impossible task of building a graduate program in zoology with neither money nor equipment and on the sandy shoals of an inadequate undergraduate department. The Rosenwald grant itself $8O,OOO to be administered by Howard was dribbled out to Just with such mindlessness that at the end of the five-year period of the grant, it was found to be grossly underexpended: $12,000 had to be returned. Sometimes the frustration reached comic levels Just was once denied a laboratory request for 500 amoebae because the dean feared they would "swarm over the campus like a herd of elephants."

It was especially poignant that Just fared no better among his black colleagues than he did among his white ones, and when, in 1941, it was all done, Frank Lillie's memorial tribute to E. E. Just lamented more than his death: "Just's scientific career was a constant struggle for opportunity for research, the breath of his life... Successive fellowships and research awards bear witness to the high esteem in which he was held as scientist, but all these appointments were limited as to time, and Just never experienced the security of a life appointment adequate to carry out his work... That a man of his ability, scientific devotion, and of such strong personal loyalties as he gave and received, should have been warped in the land of his birth must remain a matter for regret."

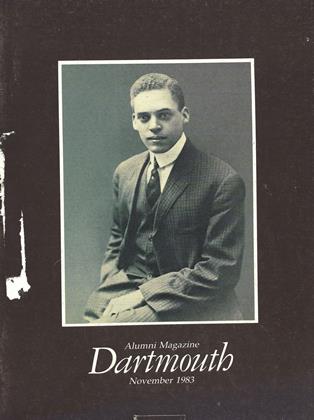

BORN in Charleston, South Carolina, in 1883, Just was sent north for schooling by his widowed mother, Mary Just, an educator and religious leader who founded one of the first

industrial schools for blacks in South Carolina. The young Just had read in a religious magazine about Kimball Union Academy in Meriden, New Hampshire, and, with "five dollars and two pair of shoes," he worked his way north to attend school there. He was a star student at Kimball Union, and going on to nearby Dartmouth College seemed the natural thing to do.

A scholarship student at Dartmouth, Just was the only black in a class of 287, and he completed his first year with passing grades in mathematics and oratory, very good marks in English, French, and Latin, and the highest marks ever made by a Dartmouth freshman in Greek. But Just had been ill prepared by the benevolent mistresses at Kimball Union for the competitive world of an Ivy League college with a casual approach to academics and an emphasis on fraternities, football, and future business contacts. His sophomore slump was classic. Taking a heavy, seven-course load, Just fell into a pattern of missed classes and skipped chapel exercises. He was docked grade-points as punishment and received D's in most of his courses. He sat makeup exams in the spring, however, and the following year he settled into stride, achieving a 92 average and becoming the junior class's only Rufus Choate Scholar.

By that time, Just had come under the spell of Dartmouth biologist William Patten, a Harvard graduate with a Leipzig doctorate. Patten was a dynamic teacher who had made his reputation in research on evolution, and that year Just's science marks were better than his marks in Greek. His dedication to classics was being undermined, and the sympathy and inspiration he received from another biology professor, John Gerould '90, clinched the matter. During his senior year, Just exhausted the College's offerings in his new major, biology, and nearly exhausted its offerings in history, his minor.

At commencement, Just took high honors, graduating as the only magnacum laude student in his class, with special honors in zoology and history (the first such dual recognition in Dartmouth history), honors in botany and sociology, and the Grimes Prize for Seniors. He had been two years a Choate scholar and was elected to Phi Beta Kappa.

Recruited by Howard straight out of Dartmouth, Just was hired through an administrative misunderstanding as an instructor in English. He went to Washington and threw himself into the job of teaching. He also helped the students organize the university's first drama club and the country's first black fraternity, Omega Psi Phi. The following year he was "discovered" as a scientist and asked to help revitalize Howard's flagging biology program. Soon thereafter, Just contacted Patten for advice about graduate training in biology.

Patten tried to steer Just away from pure science toward medicine, where, at least among blacks, a black man would have a reasonable chance at a successful career. But Just insisted on biology, and Patten contacted his colleague Frank Lillie, head of the department of zoology at the University of Chicago and director of the Marine Biological Laboratory at Woods Hole, Massachusetts. Lillie agreed to take Just on.

THE Marine Biological Laboratory (MBL) had been set up in 1888 in the tiny Cape Cod town of Woods Hole. Modeled after the marine laboratories of two great zoologists, Anton Dohrn of Naples and Louis Agassiz of Harvard, it was designed as "a sea-side laboratory for instruction and investigation in biology." (Proximity to the sea is important to research biologists because marine invertebrates offer relatively simple models for the biological systems common to all forms of life. For embryologists, such as Just, they also provide an abundant and easily obtainable supply of eggs and sperm.) Each summer, bright young biologists from all over the world gather at the MBL to work as research assistants to the senior men and women who constitute "the biological mighty" and to enroll in courses given by them.

Just spent the summers of 1909 and 1910 taking graduate courses and working as Lillie's assistant. He collected hundreds of specimens, from squid to horseshoe crabs, and labeled, identified, and drew them. He worked diligently at dissecting and imbedding marine eggs for Lillie's work on fertilization. And he watched the fascinating process of cell division through the lenses of his microscope. In the summer of 1911, after being promoted to associate professor of biology at Howard, he enrolled in absentia as Lillie's student in the doctoral program at the University of Chicago. Lillie and he worked together on the fertilization and breeding habits of the marine worm Nereis and the sea-urchin Arbacia, and Lillie set him the task of investigating the pattern of cell cleavage in Nereis eggs.

This fundamental mystery of biology how an apparently formless egg, a single cell, develops into a complex, many-celled, and symmetrical adult is still not fully explained. But Just made inroads on the problem that year and in 1912 published his results in a paper the first of more than 70 he was to publish during his lifetime. His investigations showed that the belief that the line of the first cell division in a fertilized egg invariably conforms to the midline of the developed embryo was wrong. In the eggs of Nereis, Just proved, the sperm entrance point is critical in determining the first line of cleavage.

That same year he was made full professor of biology and professor of physiology at Howard, and he married. His June bride was Ethel Highwarden, an instructor in German at the university. The daughter of one of the first black women graduates of Oberlin College, Ethel was also a descendent of William Whipple, signer of the Declaration of Independence. Over the next decade, she was to bear Just three children Margaret, Highwarden, and Maribel before the marriage foundered (in part because of Just's increasing involvement with the white academic world at Woods Hole, whose social arbiters tolerated Just because he was a scientist but did not welcome his dark-skinned family).

Just spent all but two of the next 20 summers working at Woods Hole. He and his mentor Lillie were both quiet, reserved people and, mutually appreciative, they worked well together. Both were diligent and meticulous, and their habit of working side by side in complete silence became a standing joke at the MBL.

At Woods Hole, Just noticed with amazement how often physicists, chemists, and biologists, while taking great trouble to insure that their apparatus was top-notch and their chemicals pure, seemed not to care about the condition of the living material they used. Just himself was always very careful not to damage the specimens that went into his experiments, and he came to know more than anyone else around what constituted normal conditions for marine eggs. Once asked to help an MBL research team correct a 50 percent failure in specimen development, he put his finger on the problem immediately: the team's collecting pails were not being shielded from the heat of the sun during the short trip from the dock to the laboratory. The MBL community came to consider Just "a genius in the design of experiments."

Just suffered somewhat from this reputation, in that he was constantly interrupted by other investigators. "He was in great demand," recalled Lillie, "especially by physiologists who knew their physics and chemistry better than their biology." Just was generous with his advice and his assistance, but over time he came to feel, with some justice, that because white investigators were willing to expose their ignorance more to a black man than to their white colleagues, he bore an unfair burden in this regard.

Just completed his doctorate in 1916, a year after he became the first recipient of the now-famous Spingarn Medal, presented annually by the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People to "the man or woman of African descent who shall have made the highest achievement during the preceding year, or years, in any honorable field of human endeavor." He continued to work rather quietly as Lillie's protege until 1917, when his own original research with egg cells was begun.

As it commonly occurs, the cell consists of a mass of protoplasm, or living substance, in which a central discrete body, the nucleus, is surrounded most often by a clear substance called cytoplasm. The egg cell is especially interesting, for out of it emerges the complex organization found in the adult multicellular animal or plant. The cell is the biologist's crucial unit of observation, and the egg cell is the special domain of the embryologist.

Working with the eggs of Echinarachnius parma (the sand dollar), Just investigated, among other things, the response of the cortex the surface layer under the egg's membrane to insemination. In 1915, he had observed and compared insemination with chemical agents and insemination with sperm and concluded that "whether by sperm... or by artificial agents, the initiation of development is fundamentally the same," a conclusion which in his mind supported the theory that fertilization is essentially a process of the egg, not, as was then thought by many, the effect of a molecular substance, a "life molecule" or "cytolyzer," carried by the sperm. Just felt it was a substance secreted by the egg, one that reacted with both egg and sperm, that initiated development in fertilization, and his experiments settled the fact that it is the reacting biological system that is important in egg development, not what is applied to it.

This pathbreaking work established Just as an outstanding scientist and commended him to the attention of foundation officials, particularly those of the Rosenwald and Carnegie funds. It also brought him the enmity of an entrenched school of biologists whose theories his own work brought into question and whose influence with the foundations was to plague Just throughout his career.

One of Just's greatest contributions to embryology was his insistence on the importance of what he called the ectoplasm. He felt that the cytoplasm of cells consisted of a central, more opaque zone, the endoplasm, which contained various inclusions, and a narrow peripheral zone, the ectoplasm, which was optically empty. In the ectoplasm, Just thought, were to be found structures peculiar to living matter.

At the time that Just began this work, most biologists saw the nuclear component as the "kernel of life," an emphasis Just wanted to shift. He wanted to demonstrate "how far life processes are related to the dual and reciprocal components, nuclear and cytoplasmic structure." He wanted to spell out the role of the ectoplasm in vital manifestations, which had not yet been done for a simple enough reason. Compared to the nucleus, the ectoplasm was difficult to observe with the light microscope.

This is not to say that Just ignored the nucleus. His major work a book published in 1939, two years before his death makes clear his belief in the protoplasmic system involving both nucleus and cytoplasm. He saw in the nucleus an expression of the tendency to fixity, rigidity, and resistance to change: "This tendency aids to preserve individual integrity which hands over intact from generation to generation the character of the organism." The ectoplasm expressed for Just the tendency toward change: "On the other side, the living thing is highly mobile, changing with every change in the environment, accommodating itself and thus evincing capacity for self-regulation. In the protoplasmic system the ectoplasm is the region of active momentary changes in response to environmental conditions."

Just went on to theorize that because during cleavage, the nuclear material increases while the cytoplasmic material decreases, it is logical to assume that the nucleus is drawing chemical substances from the cytoplasm, which with each successive chemical withdrawal becomes itself a different compound, available for a different reaction with the developing nucleus: "The progressive differentiation of the egg according to this conception is brought about neither by the pouring out of stuffs by chromosomes into the cytoplasm nor by segregation of embryonic materials as postulated by those who uphold the theory of embryonic segregation, but by a generic restriction of potencies through the removal of stuff from the cytoplasm to the nuclei." For Just, then, experimentally-induced mutations produced by temperature changes, irradiation, and so forth were due not to direct action on the chromosomes, but to altered cytoplasmic reactions that preceded the chromosomal changes. Thus, he felt, it was possible for environment to condition heredity in the basic unit of life.

The cell surface, as the mediator between the cell and its environment, came to hold an almost spiritual fascination for Just. Here was to be found not only an explanation for such fundamental processes as fertilization and embryonic development, but perhaps also an answer to the mysteries of heredity and evolution. Life, Just felt, could not be "only a struggle against the surroundings from which life came." It must be a form of cooperation. He adopted the theory of the Russian anarchist philosopher Prince Peter Kropotkin, who believed mutual aid and cooperation to be the fundamental fact of the biological world a view that Just found preferable to the post-Darwinian idea of a struggle for existence.

Just became an established authority on the phenomenon of fertilization. He was the first to report a "fertilization wave" in the cortex of the egg cell. This evanescent phenomenon, which Just called the "wave of negativity,' is part of the mechanism by which polyspermy is prevented in fertilization. The fascinating sequence that Just observed through the lenses of his microscope is recounted by Kenneth R. Manning in his new Oxford University Press biography of Just: "By adding to eggs a drop of seawater containing a few spermatozoa, Just was able to observe a most fascinating phenomenon. Within two seconds, the spermatozoa attach themselves to the Arbacia eggs, for example. The egg surface shudders back and forth from the impact of the spermatozoon, and the egg membrane goes in and out underneath the darting spermatozoon for a second or two. Then the spermatozoon stops, and buries its tip in the egg surface, and the ectoplasm begins to take on a cloudy appearance. Within twenty seconds the ectoplasm is completely cloudy. Then, 'like a flash,' beginning at the point of sperm attachment, a wave sweeps over the surface of the egg, clearing up the ectoplasm as it passes."

It was a major breakthrough, in which Just predicted something that only very recently has been demonstrated. We now know that when eggs are fertilized, there is first an electro-chemical reaction, which is followed by a burst of calcium released from the point of entry of the sperm. The calcium wave surrounds the egg, and changes occur, one of the most important of which is the rupture of cortical vesicles or granules that release a substance that hardens the egg membrane. The membrane then pulls away from the cortex and thus mechanically prevents the entrance of any other sperm. Recent work by Lionel Jaffe and others, using bioluminescent tracers, has produced actual photographs of the phenomenon that Just observed fifty years ago through a light microscope.

But the increasingly difficult attempt to find secure funding for his research, exacerbated as it was by a lifetime of racial slurs, took its toll on Just. When in 1929 he accepted an invitation from Anton Dohrn's son Reinhard to work for a summer at the famous Stazione Zoologica in Naples, he was already badly disillusioned. He was dismayed about the "really bad biology physico-chemical stuff" that Lillie and others were allowing to go on at the MBL, and his dismay was compounded by his being constantly dunned for help because of his own "good" biology. He was beginning to be irked at being "mid-wife to the investigations of others."

Accompanied by his 16 year old daughter Margaret, Just took ship in January for Naples. His reputation in Europe had long outstripped the one he enjoyed in this country, in part because there they were doing his sort of biology and tackling the questions that intrigued him. He was the first black scientist of any nationality to work at the Stazione Zoologica, and the administration's response to his visit was a revelation. The concern of the director, Reinhard Dohrn, that everything go just right, even to his meeting Just personally at the dock despite a bad case of the flu, was a recognition not only of Just's status as a scientist, but also an awareness of him as a human being. It opened Just's eyes to what he had been contending with in his own country.

In Naples, he met scientists from all over Europe, 'and he was struck by how much interest they showed not only in his work but also in him. At the MBL he had, he felt, often been treated like a mere encyclopedia. European scientists seemed to him "more human" than those in America; they seemed to live "a more natural sort of life... gentle without being soft." No less productive than their American counterparts, they produced with "less sound and fury" and more concern for each other as people. Coffee breaks at the Stazione were graced with conversations about Strauss and Picasso, Just observed, and he found the tone always earnest and sensitive, never glib. (Of course, the Stazione Zoologica was run rather feudally, unlike the democratically arranged MBL, but Dohrn was a benevolent dictator and Just did not suffer from that difference.) In Naples his research went well, and everyone was kind. The women scientists were taken with his looks and charm, painters urged him to sit for portraits, and Just found the Europeans open and intimate and outgoing in a way that even his closest friends at Woods Hole had never been.

Just developed a close colleagial bond with Dohrn, and began, after his daughter returned to the United States, an intense relationship with Margaret Boveri, daughter of the noted embryologist Theodor Boveri. For the first time, he felt free to think philosophically, and he wrote about this time that his "little inconsequential finger pokings at the problems of nature" were being transformed into a "peculiar... love for things human (and earthy) and a transcendentalist outlook ... a beautiful mixture of reality and idealism." He was, he felt, finding a "more soul satisfying attitude toward life" than he had ever before thought possible.

At the end of the visit, however, the heavy teaching schedule and the political mess at Howard had to be picked up again. He still had a family to support, even if it was more or less estranged. The following year, Just was invited as guest professor to the Kaiser-Wilhelm-Institus in Berlin. Infatuated with Europe, he accepted and spent the time working with other scientists to see whether by close cytological study it was possible to determine the mechanisms by which cancerous cells are created through exposure of eggs to ultraviolet light. The work suggested to Just that there were important but quick and barely discernible changes in the cortex during development that had not yet been investigated seriously by embryologists.

After Berlin, he returned to Woods Hole to be on hand for a celebration of Lillie's 60th birthday. As Lillie's most prized student and best friend, Just delivered his festschrift paper last; he then stepped off the podium and said, "I have received more in the way of fraternity and assistance in my one year at the Kaiser Wilhelm-Institut than in all my other years at Woods Hole put together." He left the astonished assembly without saying goodbye to anyone and never again returned to Woods Hole. The rest of his summers were to be spent in Europe.

He was invited to work in the Prince of Monaco's private laboratory and read a paper at the Congress of Zoologists in Padua. He lectured in Graz, at Oxford, and at Cambridge, and he worked at the Sorbonne laboratories in Paris. During the academic months, he returned to his teaching duties at Howard and to the ever-draining and ever-unsuccessful search for research money. Then, in Berlin, in the summer of 1931, he met Hedwig Schnetzler, a German philosophy student. They became lovers, and with her help, he began to reassess his life. When he returned to the United States, he started standing up for his rights as a scientist and as an oppressed black man. This stance brought him to open loggerheads with the administration at Howard, which stepped up its pressures in response. Teaching and committee work kept him on campus up to 14 hours a day. His research was suffering. He had to leave Howard. But no white institution in America would hire him.

Just longed to emigrate to Europe. But though there were invitations aplenty in pre-war Europe, there was no money there. Nor could he get his wife to agree to a divorce, though he and she were by then completely estranged. His solution to all these difficulties was to spend his summers with Schnetzler in Europe, living sparely and working with her at the articulation of his burgeoning theories. He was writing his magnum opus, TheBiology of the Cell Surface.

In 1939, Just obtained a divorce, and he and Schnetzler were free to marry. They intended to remain in Europe but were driven out of Germany and then out of France by the Nazis. They returned, reluctantly, to this country, and Just took up his duties once again at Howard. Just's fourth child, Elizabeth, was born in 1940. The following year, Just succumbed to pancreatic cancer. He died at the age of 58, disillusioned and to an unknowable extent unrealized. Within a few years, the name of E. E. Just sank into obscurity.

THIS year is the centenary of Just's birth, and by a timely coincidence, it is also the year that Oxford University Press has brought out his first full length biography. Kenneth R. Manning, professor of the history of science at MIT, wrote the biography, Black Apollo of Science. In resurrecting Just for his book, Manning also interested other people in him, with the result that this year will see celebrations of E. E. Just in Charleston, South Carolina, and at the MBL.

Modern day MBL embryologist William Jeffery of the University of Texas explains that Just fell into obscurity largely because he had no opportunity to train graduate students who would carry on his scientific traditions and thus his memory. Jeffery himself first encountered Just's name in the acknowledgements section of a modern handbook of laboratory technique that is based largely on Just's book Basic Methods for Experimentson Eggs of Marine Animals.

Asked to comment on Just's work, Jeffery explains, "There were two camps here then the embryologists and the physiologists. The physiologists were in vogue because their theories of studying biology through chemical means were new. They studied all sorts of cell properties not studied before, one of which was the cell membrane, which they studied merely as a physical entity a thin group of molecules. Just said there was more to the cell surface than just a thin membrane: there was something underneath, something important, which he called the ectoplasm."

The physiological view continued in vogue, despite Just's work, for the next 30 years, according to Jeffery: "Finally, in the seventies, we understood that cells are not just bags of liquid in membranes. Under the membranes are cytoskeletons, gel-like structures, proteins, fibers, granules. Just saw all of that, using only a light microscope."

The cell surface was, in fact, "taboo" in Just's day. "Everybody was looking in the nucleus," explains Jeffery, "hunting for DNA. In the last ten years, however,* the whole rage in biology has been the cell surface, especially in cancer research. It is being seen today as Just saw it half a century ago as what regulates what goes in and out of the cell."

Just's ideas about the determining role of the cytoplasm are also being borne out, says Jeffery: "We think today that in many eggs it is not the nucleus that determines the cell types but the materials from the cytoplasm. Recent work by John Gurdon of Cambridge University suggests a totopotency in the nucleus and a restrictive determination in the cytoplasmic environment. Some of the corroborative work now being done here involves investigations with a tunicate, the sea squirt, in whose eggs the different cytoplasmic areas are easily discernible because they are different colors unlike those of most cells. The part of the sea squirt egg's cytoplasm that gives rise to muscle cells, for instance, is yellow, and the nucleus of any sea squirt cell put into the yellow cytoplasm develops into muscle cell."

"Jast was a poet," remarks Jeffery I in speaking of The Biologyof the Cell Surface, from which he quotes an obviously favorite passage: "We feel the beauty of Nature because we are part of Nature and because we know that however much in our separate domains we abstract from the unity of Nature, this unity remains. Although we may deal with particulars, we return finally to the whole pattern woven out of these. So in our study of the animal egg: though we resolve it into constituent parts the better to understand it, we hold it as an integrated thing, as a unified system: in it life resides and in its moving surface life manifests itself."

Just's death was reported in the class notes section of this Magazine with the comment, "It is unfortunate that his remarkable achievements have not been more widely known and appreciated by his classmates. No record of accomplishment in our class is more worthy than his and certainly few have equaled it." Forty years later, in 1981, Howard University named a biology building after him. Last year, in 1982, Dartmouth College established a chair in his name. As his student and reviewer Montague Cobb once wrote, "Some things take a long time."

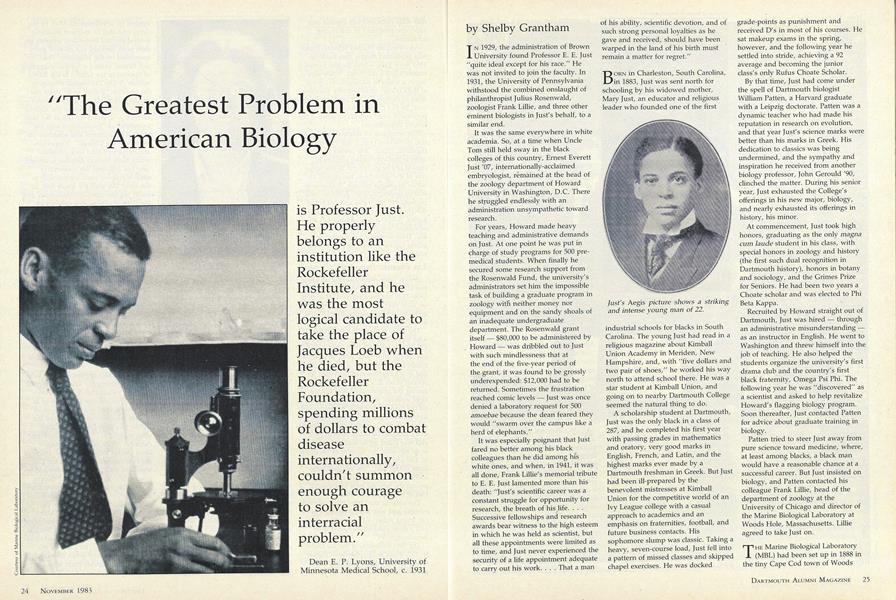

Dean E. P. Lyons, University of Minnesota Medical School, c. 1931

Just's Aegis picture shows a strikingand intense young man of 22.

The Lillie Building, constructed duringJust's student years at the MBL, servedas the laboratory's main lecture hall. Itsauditorium was the scene of Just's curtfarewell to Woods Hole in 1930.

Pitching horseshoes was a favorite pastime among the young scientists at the Marine Biological Laboratory.

The Brotherhood of Man is riot so much a Christian doctrineas a fundamental biological law. For biology does not andI cannot' 'recognize any specific differences among humans.This is a fact of tremendous significance for theHuman family. The peace of the world lives here.And the transcendent value of science to manwill be measured in just proportionto which we can realize this truth.E.E.Just

When an egg of the fresh-water fish medaka is fertilized after being injected with aequorin, a bioluminescent substance activatedby calcium, it is possible to photograph the calcium wave that passes over an egg as part of the process that preventspolyspermy. Just predicted such a "wave of negativity" half a century earlier. Starting at the animal pole (the point of entry ofthe fertilizing sperm), the wave traverses the egg as a shallow band that vanishes at the antipode minutes later. The last frame isa tracing of the leading edges of the 11 illustrated wave fronts. (These photographs originally appeared in a paper published in1978 by John Gilkey, Lionel Jaffe, Ellis Ridgway, and George Reynolds.)

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureGiving the Rush to the Record books

November 1983 By Brad Hills '65 -

Feature

FeatureJohn Singer Sargent: Last of the Great Portrait Painters

November 1983 By Richard Stuart Teitz -

Sports

SportsSports

November 1983 By Kathy Slattery -

Books

BooksAll Biology Is Indebted . . .

November 1983 By Peter Smith -

Class Notes

Class Notes1979

November 1983 By Burr Gray -

Class Notes

Class Notes1978

November 1983 By Anne Barschall

Features

-

Feature

FeatureRobert S. Oelman '31 Heads Alumni Council for 1954-55

July 1954 -

Cover Story

Cover StoryIrving L. Weissman '61

March 1993 -

Cover Story

Cover StoryTALES OUT OF SCHOOL

MARCH 1995 -

Feature

FeatureBattle Scarred

Sep - Oct By JAMES WRIGHT -

FEATURE

FEATUREMeanwhile, In Illinois

NOVEMBER | DECEMBER 2015 By JULIA M. KLEIN -

Feature

FeatureThe Arts in Our Colleges

JANUARY 1963 By WILLIAM SCHUMAN, L.H.D. '62