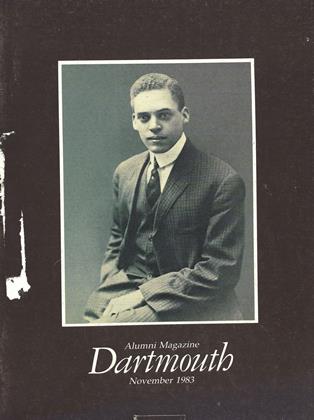

BLACK APOLLO OF SCIENCE: THE LIFE OF ERNEST EVERETT JUST by Kenneth R. Manning Oxford University Press, 1983, 397 pp., $29.95

I dreaded to read this book. Following Dr. Just nearly a quarter century later, I arrived at Dartmouth like him by crazy luck, then went to the MBL at Woods Hole and on to graduate study and a career in experimental embryology, inspired and urged on by the same two professors, William Patten and John Hiram Gerould. Just's tragic last two summers at Woods Hole were my first two happy ones. I was there learning to find, care for, and experiment with the marine organisms he had worked with, wearing out my copy of the uniquely valuable handbook of methods he had put out by popular demand. Later I reviewed for this magazine the extended version of it that he published in 1940, the year of his escape from the Nazis. When that book went out of print some years after his death I had the honor to help with an updated version of it. All of us young people at Woods Hole knew of his brilliant experimental work, much of which I had read as an undergraduate under Gerould. We admired him personally, and knew in a vague way the hell he had been through on the way from invisible man to internationally famous scientist. But we were spared the details.

Now we have them, overwhelmingly. I shall cringe every time I think of this book. All biology is indebted to Manning for attempting the job and carrying it off in thoroughly scholarly fashion.

To be sure, in many long pages he has allowed himself to guess what went on in Just's mind, describing his supposed emotions and thoughts as in a novel rather than letting the events speak for themselves. But he has obviously talked with most of Just's surviving intimates, visited the labs where he worked, and read every scrap of paper referring to him that still exists over a thousand of which are cited. I can hardly doubt that his portrait of the man is faithful and true.

He had a problem with organization. The book gains something by his decision against a month by month, year by year chronology, but loses by quite a lot of repetition. The first chapter races through Just's ancestry and birth and on to his 1907 graduation from Dartmouth with highest honors, and the last one too quickly hurtles through the collapse of his world and his painful death. Most of the others deal with intervals of years at particular places (Howard University, Woods Hole, Europe). But since Just was continually shuttling from one of these to another (18 summers at the MBL, most winters in Washington, about a dozen visits of varying length in Europe), this pattern presents the reader with a good many flashbacks and much reiteration. In particular, one long middle chapter deals with Just's almost lifelong Hair breadth Harry hunt for grants to support his research and travel, yet the pieces of this story have to be woven into most of the other chapters too.

But these are quibbles. Beyond this, I do have to question whether the author has distinguished well enough between the hostility that Just met in his general circulation among Americans because of the color of his skin, and the degree of openness and friendliness he met among his colleagues in American science. The difficulty of getting grants has been felt by most biologists before and since. The fact is that Just did succeed by his persistence and on his own merits in getting grants almost continuously from 1920 to 1933 from such distinguished and hardpressed agencies as the Rosenwald Fund, the General Education Board and the Carnegie Foundation, in addition to his inadequate salary from Howard University.

And after a slow beginning of utter shyness, he gradually did become a well liked and happy part of the social life at the MBL, particularly among the younger folks. The outrageous snubs that his wife and children experienced the one summer they came to Woods Hole and that so soured him on the MBL were not the interactions of scientist with scientist, however inexcusable. Just certainly had his share of memberships in scientific societies, and invitations to symposia, editorships and contributions to multi-author compendia.

The author slips into journalese sometimes with reference to "the raging of scientific controversies," and the rejection of some of Just's ways of interpreting data. History is full of grisly and brutal theological and political disputes, but I have never known a raging controversy between scientists. We do not operate that way. The account of the zoologists' meeting at Princeton in 1935 (page 279) is a case in point: Just is said to have "faced old antagonists," Conklin "attacked him" with a hostile "outburst." Maybe Just recorded these words in letters. I was at the back of the crowded room at that productive session and I remember the clearly and politely expressed differences of opinion, not about the results of experiments but about the different ways of interpreting them. There was not only no hostility and no outburst, we all had a relaxing chuckle when old Conklin went to quote from one of his own papers but couldn't remember which one it was; Just immediately cited the title, journal and date.

Not that Just didn't bruise some feelings in such meetings and in his papers. Crusty old Jacques Loeb never forgave him for totally deflating one of his pet theories about parthenogenesis. The "Morgan crowd" the young geneticists who worked on Drosophila under T. H. Morgan but lacked his deep knowledge of embryology were taken aback by Just's insistence that their chromosomes were merely the storehouses of information whereas it was the cytoplasm that brought about differentiation during embryonic development. Nevertheless we all know this arguing was all good and proper, the very essence of what the philosophers have called the "self-corrective" aspect of the institutionalized method of science.

Dr. Just craved all his life to move to a job at a university or other research base better suited to his needs than half-starved, badly administered How are University. It deeply hurt him when better placed friends had to tell him he couldn't make it simply be cause of the skin-color genes he bore. This too was not scientist against scientist. I am sure he understood that these friends, from Frank Lillie on down, were deeply pained to have to be blunt with him about what they could and could not do for him, considering the climate of prejudice they lived in. Even so, he couldn't accept this without accepting defeat. The hero in him kept trying, up until that last bitter year.

I had one more minor disappointment about what is in general a powerfully moving biography. The lengthy quotes from Just's most important scholarly contribution Biology of theCell Surface, reviewed in this Magazine on its appearance in 1939 by Professor Roy Forster did not seem to me to get across its full significance. That book came at a time when genetics and general physiology were making tremendous strides and attracting many young people who hadn't the time to acquire the broad biological background of their older teachers. Fooled by the power of their new techniques, there were physiologists who talked of explaining all life in terms of physics and chemistry, and geneticists who thought their genes would explain evolution and differentiation. In the classic manner, Just attempted to bring all these special points of view into focus on that ultimate mystery, the nature of life itself: It was a worthy attempt and much appreciated at the time. Nobody reads it any more, not because the great challenges have been met by final answers to the most basic questions, but because these are now expressed in new vocabulary from new discoveries with new techniques. The elementary questions still stand, however, and we need from time to time another such eloquent synthesizer and guide, someone to recall us to the complexity, the adaptability and the sheer beauty of living systems.

W.W. Ballard '28

William Ballard, Sydney E. JunkinsProfessor of Biology, Emeritus, is stillvery active in 412 Gilman and in manyother parts of the world.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

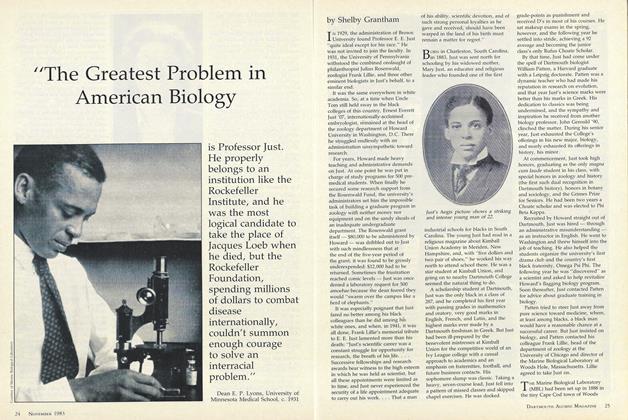

Feature"The Greatest Problem in American Biology

November 1983 -

Feature

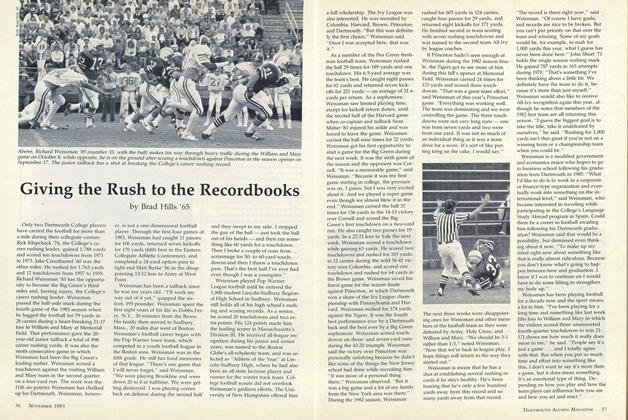

FeatureGiving the Rush to the Record books

November 1983 By Brad Hills '65 -

Feature

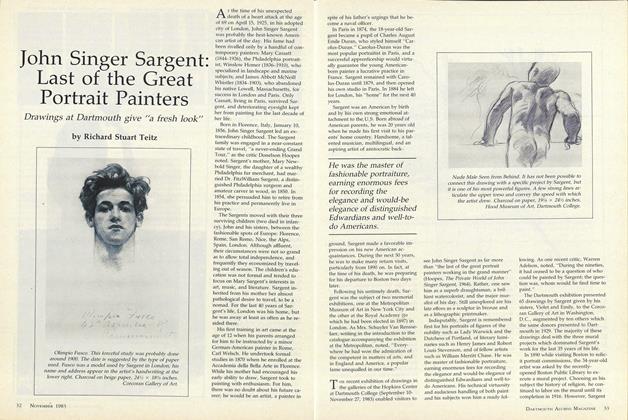

FeatureJohn Singer Sargent: Last of the Great Portrait Painters

November 1983 By Richard Stuart Teitz -

Sports

SportsSports

November 1983 By Kathy Slattery -

Class Notes

Class Notes1979

November 1983 By Burr Gray -

Class Notes

Class Notes1978

November 1983 By Anne Barschall

Peter Smith

-

Article

ArticleIn the Wide, Wide World

OCTOBER 1981 By Peter Smith -

Article

ArticleIn the Wide, Wide World

OCTOBER 1982 By Peter Smith -

Books

BooksAttentive Eye, Attentive Ear

November 1983 By Peter Smith -

Books

BooksHow Much Freedom?

JUNE/JULY 1984 By Peter Smith -

Feature

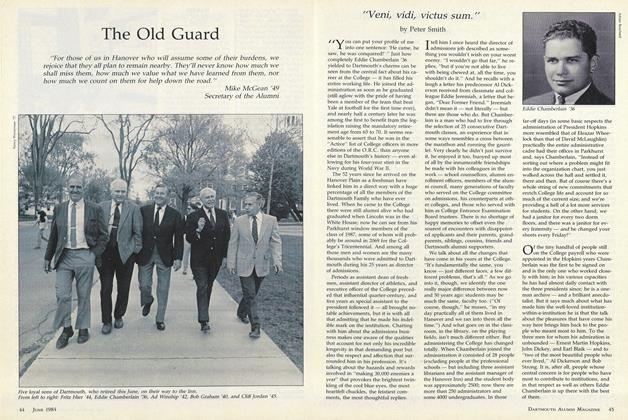

Feature"Veni, Vidi, victus sum."

JUNE/JULY 1984 By Peter Smith -

Books

BooksSo Much More

NOVEMBER 1984 By Peter Smith

Books

-

Books

BooksAmerica's Town Meeting of the Air.

April 1936 -

Books

BooksSet of Freud Presented

JUNE 1967 -

Books

BooksSADDLING PEGASUS

JANUARY 1932 By F. Cudworth Flint -

Books

BooksPETROLEUM AND COAL

FEBRUARY 1930 By H. M. Bannerman -

Books

BooksF as in FLIGHT

May 1948 By H. M. Dargan. -

Books

BooksWhale of a Man

May 1981 By Peter C. Grenquist '53