Education at Dartmouth receives crucial support from the three major academic centers: the Library, the Hopkins Center for the Arts, and the Kiewit Computation Center.

One of the very happy events of my first year in office was a meeting of the Board of Trustees at Keene, New Hampshire, in the very same room where the Board first met in 1770. At this symbolic meeting the Librarian, Ed Lathem '51, presented the one millionth volume in the Dartmouth collection. This book, acquired through the generosity of the Friends of Baker Library, was The Tenth Muse by Anne Bradstreet, one of the few existing copies of the earliest work of American literature.

With its more than one million volumes, the Dartmouth Library is one of the largest open-stack libraries in the world. As one who has on occa'sion had to battle his way through closedstack libraries, I can testify to the enormous pleasure of being able to browse on one's own in a first-rate collection. Without such an outstanding collection we could never attract the quality faculty that we do; therefore, it is our single most important asset in support of education.

It is also true that it is very expensive for an institution of our size to maintain so remarkable a library. The net yearly cost is more than one-and-a-half million dollars, and library costs are increasing more rapidly than for other programs. This results from a combination of unusually sharp cost increases in printing and the explosion of human knowledge. In our present financial situation we face difficult priority decisions, balancing what the institution can afford against the danger of compromising the quality of Baker Library.

A second major problem facing libraries is that as more and more volumes are published each year, the demand for physical space is ever increasing. While the first million volumes took 200 years to acquire, at current rates of acquisition the second million volumes would be acquired in 30 years. The construction of enormous new physical facilities and the cost of operating them could bankrupt the College.

We have gained some time through the construction of the Feldberg Library serving Tuck and Thayer schools and the Kresge Library for the physical sciences, as well as through an addition to the Dana Biomedical Library. During the years of expansion made possible by these facilities, we must find a solution less disastrously expensive than keeping two or three million volumes in an open-stack library in the center of campus.

In the long run there is considerable hope that modern technology will come to the aid of libraries. Even today microtexts make it possible to store a million volumes in one large room. But the publishing industry has not made an appropriate adjustment, and libraries continue to have to buy most works in traditional form. It will also require a period of psychological adjustment for users; it is very pleasant to be able to thumb through a beautifully printed book. I am quite certain that book publishing will not disappear as an art and that volumes frequently used by many people will continue to be kept in traditional form. But the vast bulk of a collection such as that of Baker Library is for reference purposes, and any one volume of that collection is rarely used. In such cases the present form of publication and storage is incredibly wasteful and will no doubt disappear.

There is the possibility of even more spectacular technological help in combining computers, modern communications equip- ment, and microtext publication techniques. A national reference library network could tie together the major libraries in the country and give quick access to any of the members. This would significantly reduce the cost of individual libraries and permit them to perform a much more efficient service for millions of users. I accepted membership on the National Commission on Libraries and Information Sciences with pleasure, as I hoped that we might make real gains through the marriage of technology and libraries. While I still believe that such progress will occur, and that it requires the initiative of the federal ment, I found that the political atmosphere was not conducive to rapid movement. I hope that during better economic circumstances, and with a more progressive federal administration, the government will take an initiative that will benefit all libraries in the country.

Under the imaginative direction of Ed Lathem, the Dartmouth Library has played a pioneering role in the use of technology to improve services. Ours has been one of the few libraries to experiment with the production of microtext materials, and we have just completed the Berkeley F. Jones Microtext Center in Baker. We have provided a leadership role for a consortium of New England libraries in automated cataloging of books, an excellent example of how one can give much more rapid and accurate service while at the same time reducing appreciably the cost of the operation.

Thus, while I see hope in the long run, our libraries will not be able to wait until the day that technology comes to the rescue. As an interim solution to the space problem, we may have to build a warehouse somewhere off the main campus where rarely used books can be stored inexpensively. Presumably, a book that has not been used in the last six months would not be so urgently needed that the person requesting it could not wait 24 hours for delivery. The advantages of such a system would be that the warehouse would not occupy space on the central campus, that it could be of relatively inexpensive construction, that several times as many volumes could be stored in a given space, and that much less staffing would be required than in the main library. Dartmouth is also exploring cooperative ventures to share library resources with other institutions.

When Hopkins Center was first constructed, it received an enormous amount of comment as one of the most striking buildings on campus, but few predicted the tremendous impact it would have on the College.

Last year some 600 cultural events took place in Hopkins Center, with 250,000 people attending them. Those figures would be impressive in a major city and are truly amazing in the north country. Hopkins Center, with its remarkably ambitious programs in music and drama and art, has become the major cultural center for a region that reaches far beyond the limits of Hanover. Sir George Solti and the Chicago Symphony do not usually visit towns with a population of 6,000, but they have been in Hanover twice during the past three years.

While drama and music were popular extracurricular activities in the past, the level of participation and the sophistication of the student participants has risen amazingly since the completion of Hopkins Center. In addition to significant enrollments in all three of the departments, about one-quarter of the undergraduate body participates in extracurricular activities in drama, music, and the visual arts. The annual student art show has become one of the most talked-about events in town. And while the coming of coeducation has certainly helped the arts, the explosion of stu- dent interest in the creative arts predates coeducation.

What is hardest to measure is the degree to which the existence of Hopkins Center had influenced the composition of the student body. While the number of majors in the three departments is still relatively modest, we now attract many outstanding students who would probably not have come to Dartmouth in the pre- Hopkins Center years. Credit for the high quality and wide variety of the program goes to the outstanding faculty we have been able to attract to the three departments. But very great credit must also go to the imaginative leadership provided by the director of the center, Peter Smith.

Hopkins Center's major problem at the moment is that it suf- fers from its own success. A building that once looked gigantic on the Dartmouth campus is bursting at the seams. It is teeming with students at all hours and is attracting visitors from a 50-mile radius and even farther. We have had to add design and sculpture studios in a neighboring garage and have created make-shift arrangements for dance. The center urgently needs a dance studio, a rehearsal hall for drama, and several practice roomsto accommodate the increasing number of talented student musicians. And some day the College must have a gallery that can do justice to its fine and growing permanent art collection.

A significant step in the vital role played by Hopkins Center was the creation of a board of overseers. Under the leadership of Goddard Lieberson, this distinguished board gives valuable ad- vice to the faculty and administrators whose responsibility it is to run the center. The members are a continuing resource for counsel and for the attraction of outstanding talent. They have also played a key role in constructing a development plan for the future of Hopkins Center.

Important evidence of the widening impact of Hopkins Center on our region is the creation of the Friends of Hopkins Center. This group of volunteers, most of them not connected with Dart- mouth, have organized themselves to help support the region's great cultural center. Of their many important activities the most memorable one has been a highly successful fund-raising effort, a Mardi Gras Ball with Walter Cronkite as the mystery king.

Although Hopkins Center and the Kiewit Computation Center are entirely different, in many ways their roles are similar. They both attract vast numbers of students. They both contribute enor- mously to the content of education at the College, and they provide major new opportunities for extracurricular activities. They are the two developments of the 1960s that have brought significant national and international recognition to the College.

While the physical and equipment changes at Kiewit have been relatively modest in the past five years, during that period this major intellectual tool has saturated the Dartmouth curriculum. This is the first campus on which all students (and for that matter, all faculty) gained free access to a modern computer, and we continue each year to introduce over 90 per cent of the students to the not-so-great mysteries of the computer. It is not uncommon on a week-day afternoon to have a 150-170 people us- ing the Dartmouth Time Sharing System simultaneously. (Since I happened to write this part of the report at midnight, I couldn't resist the temptation to go to the terminal in my home to discover that there were 35 people using the system at that hour of the night.) While our campus has had the luxury of a great time shar- ing system for over a decade, it is surprising that we are so far ahead of most of our sister institutions in the field of computing. Undergraduate students continue to play a major role in new software developments for the computation center. Thus, Kiewit also shares with Hopkins Center the role of providing an impor- tant outlet for the creative talents of our students. And Kiewit, like Hopkins Center, is suffering from too much success; the de- mand for computer services now exceeds its capacity.

The center is directed by Professor Thomas Kurtz, co-inventor of the Dartmouth Time Sharing System and of the language BASIC. He and a small group of dedicated colleagues continue to make significant contributions to the art of computing, and they have become important national spokesmen for making computers freely available at educational institutions for the average student and the average faculty member, rather than limiting the facility to a small group of experts.

With the recognition that even after the passage of a decade our time sharing system is one of the most powerful and flexible systems available anywhere, the College has entered upon a new venture. The Trustees have created a corporation, DTSS, Inc., for the purpose of marketing the software system developed at Dartmouth. Set up as a separate corporation, subject to federal taxes, to make it legal under the Internal Revenue code, the com- pany has had some success in attracting commercial customers, but it remains to be seen whether it will become an important source of revenue for the College. In any case, it has been successful in spreading the word on the Dartmouth philosophy of computing and has made it possible for thousands of additional people to enjoy this Dartmouth invention.

The newest addition to our academic centers is the Office of Instructional Services and Educational Research. Established with the help of a major grant from the Sloan Foundation, the of- fice is available to faculty to help expand the use of educational technology in instruction. Located in renovated space in the base- ment of Webster Hall, the office supports the use of film and television, as well as experimenting with newer technology. Developments are under way in art, music, mathematics, govern- ment, and language instruction. Some of these projects combine visual technology with the use of the computer, thus enhancing the effectiveness of both. Under the direction of William Smith, Professor of Psychology (and formerly associate dean), the new office has also absorbed the duties of the Office of Instructional Research, providing support to the dean, the registrar, and to faculty committees in conducting research relevant to the plan- ning and evaluation of the educational program.

Features

-

Feature

FeatureThe First Year

September 1993 -

Feature

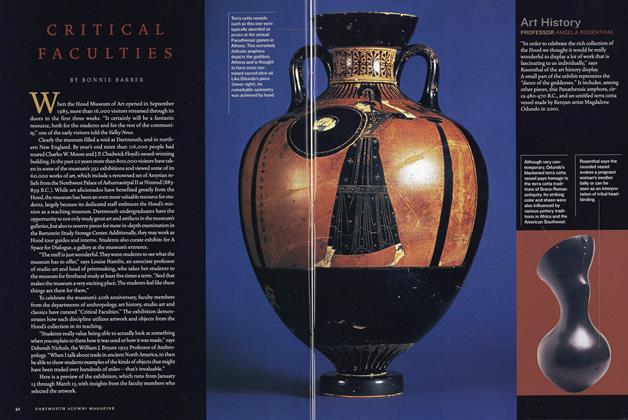

FeatureCritical Faculties

Jan/Feb 2005 By BONNIE BARBER -

FEATURE

FEATURERemnants of a Moment

MAY | JUNE 2016 By GAYNE KALUSTIAN ’17 -

FEATURES

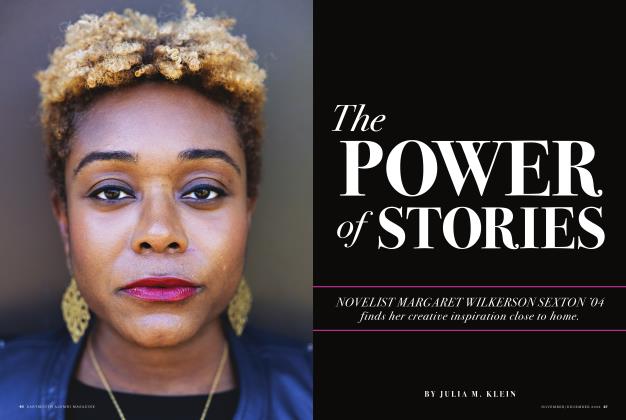

FEATURESThe Power of Stories

NOVEMBER | DECEMBER 2022 By JULIA M. KLEIN -

Feature

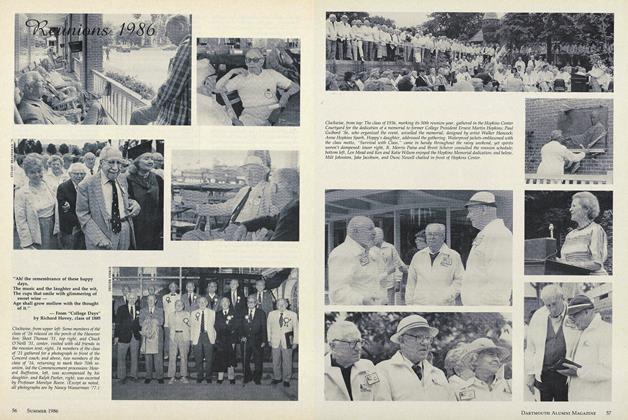

FeatureReunions 1986

JUNE • 1986 By Richard Hovey -

Feature

FeatureThe Well-Tempered Synclavier

DEC. 1977 By Woody Rothe