INUA: SPIRIT WORLD OF THEBERING SEA ESKIMO

by William W. Fitzhugh '64 andSusan A. KaplanThe Smithsonian Institution Press, 1982.295 pp. $35.00 cloth, $15.00 paper

In 1877 a young naturalist named Edward William Nelson shipped out to St. Michael, Alaska as a weather observer for the U.S. Signal Corps. In addition to this primary duty, he had been instructed by Spencer F. Baird, director of the United States National Museum, to gather data and specimens relating to the geography, zoology, and ethnology of the Bering Sea coastal region. During the next four years Nelson pursued these assignments avidly, living among the native Eskimos and traveling extensively by boat and sledge through the marshy tundra of the Yukon and Kuskokwim delta. On returning to Washington in 1881 he presented to the National Museum almost ten thousand ethnographic specimens. These constitute, according to Henry B. Collins, senior anthropologist at the Smithsonian Institution, " ... the largest, most complete, and fully documented single collection of Eskimo material culture from any part of the Arctic." That collection is the subject of Inua: Spirit World of the Bering Sea Eskimo.

The word "Inua" refers to the spirit or spiritual force that is inherent in every natural object and living thing. It symbolizes a pervasive supernatural world that the Bering Sea Eskimos must adapt to and somehow control for their own welfare. It is expressed in their shamanistic rituals and most immediately in the magical decorative art imposed on their artifacts. Further, it denotes an ever-present aboriginal sense of ecological unity with the rigorous arctic environment.

Inua is a superbly executed and fascinating book, as valuable for the expert scholar of circumpolar peoples and cultures as it will be for the non-specialized lay reader. It is not meant to be a complete catalog of the Nelson Collection, yet it embraces the entire spectrum of that assemblage. As the authors note, the book is an appreciative visual ethnography of these people: it reconstructs "traditional nineteenth-century Bering Sea Eskimo life, stories, religion, and arts" as these are exemplified in the Nelson Collection. Moreover, it is almost a manual for the art and science of survival in that part of the North American Arctic. We find clear and concise descriptions of the food and other scarce natural resources available for human exploitation, analyses of aboriginal technology, such as the specialization of hunting weapons and the development of manufacturing crafts, and always the overt or subliminal concern for the spirit world. Inua is lavishly illustrated with maps, instructive charts, and most beautiful photography, including some prints from well-nigh ancient negatives.

Several other experts have contributed significant chapters. Tom Imgalrea, a local Eskimo, tells of "The Way They Lived Long Ago," and Henry Collins recounts the story of Nelson's long sojourn in the field, the story of "the man who buys good-for-nothing things," as he was known to the Bering Sea people. Thomas Ager explains the geological and natural history of the region, and Dorothy Jean Ray and Saradell Ard Frederick deal learnedly and pleasingly with the subject of Eskimo art.

Finally, it is very satisfying to observe that Bill Fitzhugh, the senior author of Inua, began his studies in anthropology as a Dartmouth undergraduate and accompanied me on two archaeological field expeditions to Newfoundland and Hudson Bay. He and his colleagues have now produced a masterpiece.

Elmer Harp, Professor of Anthropology Emeritus,has lived among the Eskimos during periods of fieldwork.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureWhat Is Success?

March 1983 By E. R. (Skip) Sturman '70 -

Feature

Feature"Long John" Wentworth, 1836

March 1983 By Dirk Olin '81 -

Feature

FeatureYou know, what's his name . . ."

March 1983 By Nardi Reeder Campion -

Feature

FeatureOff and Chopping

March 1983 By Jean Hanff Korelitz -

Article

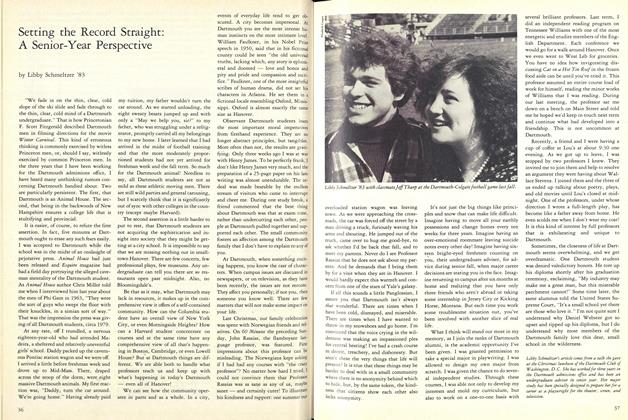

ArticleSetting the Record Straight: A Senior-Year Perspective

March 1983 By Libby Schmeltzer '83 -

Sports

SportsSports

March 1983 By Brad Hills '65

Elmer Harp Jr.

Books

-

Books

BooksCurse of Occupation

March 1980 By David Wykes -

Books

BooksWITCHES RIDE BROOMS...TO BRUSH THEIR TRACKS AWAY.

November 1954 By GEORGE R. DALPHIN '47 -

Books

BooksWEIRD AND TRAGIC SHORES: THE STORY OF CHARLES FRANCIS HALL, EXPLORER.

JUNE 1971 By KENNETH PAUL '69 -

Books

BooksShelf Life

May/June 2003 By Matt Feinstein '04 -

Books

BooksANTS WILL NOT EAT YOUR FINGERS A SELECTION OF TRADITIONAL AFRICAN POEMS.

JULY 1969 By RICHARD D. TAYLOR -

Books

BooksTHE MISSISQUOI LOYALISTS

October 1938 By W. R. Waterman