Editor, U.S. Congressman, Mayor of Chicago, friend of Lincoln,he was as flamboyant a graduate as Dartmouth ever produced

The man who appeared on the courthouse steps was immense. Six feet, six inches, 300 pounds the behemoth glared at the assembly like an irate genie just released from a millenium of captivity.

The crowd paid homage to this apparition in the traditional manner of 19th century Chicago politics. They screamed their heads off.

"Long John!" The cry went up from a dozen different voices. "Wentworth for Mayor!" Rolling, whiskey-wet Irish brogues, staccato German cries, hardedged New England accents. These; were his people the first tongues of Chicago. Together they had conceived an American metropolis, carried it in utero, seen its birth, heard its first words. He was their first great newspaper editor, their preeminent Democrat, and one of their premium Congressmen for 12 years.

Now, "Long John" Wentworth stood before Chicago in 1857 as its first "Republican" candidate for mayor.

Despite the enormity of his person, his features were still vivid. The deep-set eyes, rigid lips and square-cut jaw trebled his already awesome appearance. Standing on the courthouse steps, he gazed at his flock with a quiet scorn, not removing his hat, seemingly oblivious of the tumultuous roar. Then, as the din subsided, he uttered the most curt, chilling stump speech in American political history.

"You damn fools,"he bellowed, "you can either vote for me for mayor, or you can go to hell!"

And without another word, he turned on his heel and exited as abruptly as he had appeared. The crowd stood stunned for a moment, and then erupted into an ovation more thunderous than the first. The virtuoso had performed another masterpiece.

That kind of calculated self-indulgence was not yet in the repertoire of the precocious, 21-year-old Dartmouth graduate of 1836 who had entered the city 20 years and 100 pounds earlier. Descended from the last two royal governors of New Hampshire, the young man who arrived in Chicago in October 1836 was simply an ambitious Yankee carrying a pair of 14-inch shoes. He owned little more than $30 and a jug of whiskey, "with which to bathe my blistered feet." Yet his rise was meteoric.

Within a month, Long John was in editorial command of the weekly Chicago Democrat, preaching Jacksonian democracy, supporting the "locofocos" in their opposition to the wildcat currency of a federal banking system, and immersing himself in city charter debates.

By 1839 he owned the Democrat and had increased its circulation from a few hundred to several thousand. And despite a disastrous, short-lived experiment with daily publication, the paper soon was boasting the largest circulation west of Buffalo. In 1841, leaving his paper in the trustworthy hands of assistant editor David Bradley, Long John attended law lectures at Harvard. Upon his return, he was quickly admitted to the Chicago bar. Politics soon beckoned.

The country's sixth census had resulted in a Congressional act of reapportionment in 1842 that added several seats to the Illinois delegation in the U.S. House of Representatives. Early in 1843, the state legislature created the Fourth District from 16 heavily Democratic counties in the northeast part of the state. No Whig could hope to win there, making party nomination equivalent to election.

At the convention on May 18 in Joliet, Long John suddenly unveiled a meticulously planned, brilliantly executed campaign that already had captured a majority of the delegates. Toppling such flabbergasted heavyweights as ex-state justice Theophilus Smith, Wentworth won the nomination by a landslide and introduced Chicago to the modern age of organization politics.

As the youngest member of the 28th Congress, Wentworth created a bit of a stir in the nation's capital. Like Washington itself, Long John was a rawboned neophyte instinctively picking his way through uncharted frontiers. Charles L'Enfant's elegant city design of 50 years before had become a chaotic, sprawling, ill-lit example of unfinished urban pretense; many said the same of Long John.

But although his flamboyant, at times flippant rhetoric prevented him from receiving any permanent committee chairmanships during his many years in Congress, Representative Wentworth was hard-working and'reliable, his political sense uncanny. And if he was not a Congressional powerbroker in Washington, his personal propaganda organ, the Democrat. always helped him to maintain a strong base of local support.

Serving from 1843 to 1851 and 1853 to 1855, during some of the U.S. Congress' most tempestuous years, Long John practiced statecraft with a stunningly talented collection of Congressmen: Andrew Johnson, Hannibal Hamlin (Lincoln's first vice-president), Robert Dale Owen; and alongside Wentworth in the Illinois delegation was Stephen Douglas, a man who would surpass Long John in national renown, but remain inextricably involved with him as either ally or enemy.

Long John's checkered career included battles for furtherance of free homestead legislation and lake harbor construction, but it was his growing support of abolitionism that estranged him from his party. After the election of 1844 and President Polk's annexation of Texas, Wentworth's New England upbringing and the political leanings of his district combined to widen the gap between the young Democrat and his party's southern faction.

Despite his militant anti-slavery position, Long John welcomed Henry Clay's Compromise of 1850 as an opportunity to suspend the slavery question and return to his support of internal improvements. His political concentration on land issues also led him to extensive personal investment in rail systems and real estate. The nation's seventh census had revealed a Chicago fully six times larger than the one Wentworth had entered 14 years before, and few men of means could ignore the chance for land speculation that accompanied a rise in population from 12,000 to 30,000 since 1845.

Retiring from Congress in 1851 to monitor his growing fortune, Long John strung together a series of. lucrative purchases. With financial help from his father-in-law, he bought more than 700 acres on Chicago's southside, eventually becoming the most landed man in the city.

Editor, farmer, land speculator though Long John was all of these, he was a politician above all else, and his retirement was short-lived. Despite an acrimonious rift with Douglas, Wentworth still represented a disgruntled, free-soil faction of the Democratic party, and the "Little Giant needed its support to win the nomination of a united party in 1852.

It was a long decade away from the early days when Wentworth and Douglas had helped ink one another's campaign posters, but the two buried their differences and formed an uneasy alliance. While Douglas lost the nomination to Franklin Pierce, he still lent his support to Long John's Congressional comeback. And though the going was still not easy for an outsider, a "barn-burning abolitionist" according to some, a masterful show of personal conciliation and party orthodoxy gained Wentworth the nomination, making his election a foregone conclusion.

As he headed off to his sixth Congressional term at age 38, the future must have seemed quite bright to Long John. Standing at the center of a tenuous but workable alliance, he served as mediator for a ravaged oranization that sought a political renaissance. Perfectly happy to preside over a peaceful period of wound-licking, Wentworth happily reported in the Democrat: "The national capital was never so dull. There is nothing of excitement, nothing of interest here." But that bit of wishful thinking was published on December 31; four days later the furor over Douglas's proposal for organization of the Nebraska Territory relit the flame of frenzied debate over slavery.

With the ineffectual Franklin Pierce in the White House, Douglas began to cultivate an increasingly powerful following, and he was absolutely infuriated by any opposition from "softshell" abolitionists. For perhaps the first time in his political career, Long John was handcuffed; the interests of his party and those of his constituency were mutually exclusive. Vacillating uncharacteristically, he lost some of his free-soil support, while simultaneously suffering attacks from Douglas's newly established organ, the Daily Times.

The faltering Wentworth quickly lost the veneer that had glossed over his fragile shell of compromise. Yet he side-stepped utter calamity by adroitly withdrawing from his Congressional race and slyly declining a fabricated offer of higher office. "Should any over-anxious friend of mine endeavor to use my name in connection with a more extended constituency," he said, "I have given him no ground to recommend me."

Despite the fancy political footwork, Wentworth had been left impotent in a party that rallied around southern interests. That was when a new faction's snowballing momentum conspired with his own weakening grip among Democrats to force his hand. Carefully testing the local political waters, shrewdly assessing his own image and constituency, Long John reasoned that the voters of Chicago just might select a Republican mayor.

The group that subsequently assembled in Bloomington on May 29, 1856, was a prestigious one by contemporary or historical standards: Joseph Medill, future Chicago mayor and founder of the Tribune; Richard Yates, future Illinois Governor; Abraham Lincoln, future President of the United States. And the reluctant Wentworth sat among these leaders, helping to found the Republican Party of Illinois.

The group's nominations of William Bissell for Governor and John Fremont for President became public relations goldmines for Long John, who began making speeches for both candidates. Lincoln often shared Wentworth's platform and the twin towers usually attracted considerable attention.

But while Lincoln was maintaining a staid, image in preparation for a possible senatorial bid, Wentworth's tactics for obtaining Chicago's mayoralty were less inhibited, though no less calculated.

Sneering at his increasingly obvious courtship of support, Douglas's Times immediately took the offensive. "The drunken revelries in which for several nights he has indulged in low brothels and large saloons, leave no doubt that he has commenced campaigning," complained the paper. But Long John rode another wave of perfectly orchestrated conventioneering and received the mayoral nomination by acclamation.

In the "Bloody Election" that ensued, the northside wards reported riots, injuries, and one death. Charges of fraud shot from one side to the other. But when the smoke had cleared, Long John had received the largest majority ever given to a Chicago mayoral candidate, much less a Republican.

Yet Long John's was not an enviable job. His city had swelled to an astonishing 86,000 inhabitants. Crime was rampant. Brothels and bars dominated many neighborhoods. In only two decades, an insignificant trading post had changed to the world's fastest growing metropolis.

And Wentworth was not about to let things slip further out of control. His inaugural pledge of "retrenchment and reform" was no hollow promise, as he soon proved in an area known as "The Sands." A collection of beaten-up, tumbledown shanties along the northside lakeshore, "The Sands" was strewn with cheap lodging houses and gambling dens. The possibility of litigation, however, prevented most landlords from attempting eviction. But shortly after the election, Long John went into action.

On the morning of April 20, the Mayor, flanked by a posse and the city's first paid fire department, marched to "The Sands." Having lured most of the hard-core toughs to Brighton race track, where he reputedly arranged a $500 dogfight, Wentworth forced the remaining inhabitants into the street. In short order, nine buildings were toppled, and mysteriously (so ran the reports) six buildings suddenly were engulfed in flames. The termination was surgical, Long John-style, but the criminal element merely was displaced, not eliminated.

Meanwhile, the city's respectable elements were every bit as subject to the Mayor's capriciousness as the incorrigibles were. Though he relished the day-to-day power of patronage and unchallenged political clout, Wentworth played few favorites once he had decided upon a course of action. On the night of June 18, he summoned the police, his "leather badge force," whose uniforms and brass insignia Long John had discarded as being prodigal. Telling them it was time to clean up the city's streets once and for all, he ordered the dismantling of every overhanging sign, awning or other commercial obstruction on the downtown thoroughfares. In just one evening, the streets were stripped, the debris carted away to the municipal market building.

Merchants and businessmen were clamoring for redress by early the next morning, but to no avail. "His Lengthiness the Mayor" knew he had the public on his side. In fact, he was so confident of his action, that he defended the police force's pre-raid drinking on the grounds that he had poured each and every drink himself

Wentworth's brazen acts combined with the Panic of 1857, a national depression that had closed nearly $6-million worth of Chicago banking and industry, to create an inclement climate for reelection. Of course, Long John read the weather reports accurately, so he did the typical Chicago thing; he hand-picked a successor, John C. Haines, who was quickly clubbed "Little John."

During those last days of Wentworth's first mayoralty, the Democrat was breathing its last. In addition to the circulation inroads made by his competitors (Long John was still nominal editor-in-chief), two serious blows were struck to a paper already fatally deficient in modern equipment. First, sub-editor James Brayman was convicted on charges of postal theft, and then, the man who had carried a lion's share of the editorial responsibilities, David Bradley, died on September 8. The Democrat also was on its deathbed, and Long John had neither the time nor the need to rebuild it, so the paper was absorbed by the Tribune in early 1861.

Out of office, out of publishing, Long John continued to pursue his uniquely flamboyant lifestyle. "It is doubtful, take him all and all," said the August 1857 issue of Chicago magazine, "whether there is a man in the city who enjoys life after his own manner better than he does."

He usually lived apart from his wife, who stayed in her hometown of Troy, New York. And though she bore him five children, only one survived to adulthood. Consequently, Long John was a man offew ties, and the comment ran that during his lifetime "he changed his stopping place as often as he changed his shirt."

A living hyperbole, his image molded by a strange mixture of naive whimsy and calculated affectation, Long John survived on instinct. "I get up in the morning when I'm ready, sometimes at six, sometimes at eight, and sometimes I don't get up at all," he once said, adding his four basic rules of life: "Eat when you're hungry, drink when you're thirsty, sleep when you're sleepy, and get up when you're ready."

Increasingly at odds with many Republican stalwarts, Wentworth took a political vacation, plunging into his real estate and railroad interests. But as 1860 approached, periodicals began speculating once again. "Each day bears witness," said Chicago magazine, "that, if he is not hard at work, his enemies at least think that he IS, and are cautioning their party friends to beware his efforts."

Editors and politicos were always afraid of Long John, and with good reason; he took the 1860 mayoral nomination on the first ballot. Receiving the grudging support of Republican party regulars who had opposed his candidacy, he weathered another rough election.

Wentworth's election was quickly capitalized upon by the Republicans, who claimed it as a harbinger of the presidential race. They went so far as to choose Chicago, which now contained more than 109,000 people ninth largest city in the U.S. as the site for their convention. Long John's victory, however, in no way altered his status within the party. His sway with Republicans was further reduced as he, like many of his contemporaries, failed to recognize the severity of the impending war. His simplistic view lasted long into the conflict, which he expected to be resolved just as easily as the Mexican War. "A soldier in this war," he said as late as April 18, 1861, "stands about as much chance of being killed as he does of being struck by lightning."

At home, his second and last mayoralty was somewhat less eventful than the first, with many issues taking a back seat to national concerns. But no reign of Long John's could ever be called dull. Under the Haines administration, uniforms and brass badges had been returned to the police force. Long John, upon his return, would have none of it. He returned the patrolmen to plainclothes and leather insignia, and then shocked the city by reducing the force a full 50 per cent in the name of economy. One lieutenant, six sergeants, and 50 men were left to patrol a city of 100,000!

When the state legislature quickly reacted by establishing an independent police board in February 1861, Long John was incensed that any group should presume to infringe upon his sovereignty. So, as one of his last mayoral acts, he called together all the city's patrolmen at 2:00 a.m. on March 25. Delivering a long harangue on the advent of a new system, he summarily dismissed the entire force! And although an emergency board rectified the problem in less than 24 hours, there was a day when the city of Chicago awakened to an unpatrolled metropolis.

Wentworth's political star faded considerably after completion of his final mayoral term, though he was still intensely involved in the public arena. He was a vociferous supporter of Lincoln, an aggressive city police commissioner, and a delegate to the 1861 constitutional convention in Springfield. He even returned to Congress in 1866, though he could play neither the veteran horse-trader nor the respected sage.

So, in 1868, he returned to Chicago and built his dream house, a 5,000-acre farm on the city's western edge. Living there after his wife's death in 1870, the revered old man employed his pen and oratory on behalf of local historical societies. He was a living, legendary vestige of Chicago's first days.

The long, white gabled house no longer stands at the corner of Archer and Harlem Avenues in Summit. Its unpretentious, serene appearance would belie the raucous, rowdy reputation of its builder, whose death in 1888 elicited a series of reminiscences about a 50-year public life that had marched in lock-step with Chicago's own audacious history.

Where a strapping, eastern college youth had found an unchartered swamphole, a portly, ancient titan departed his nation's second largest metropolis.

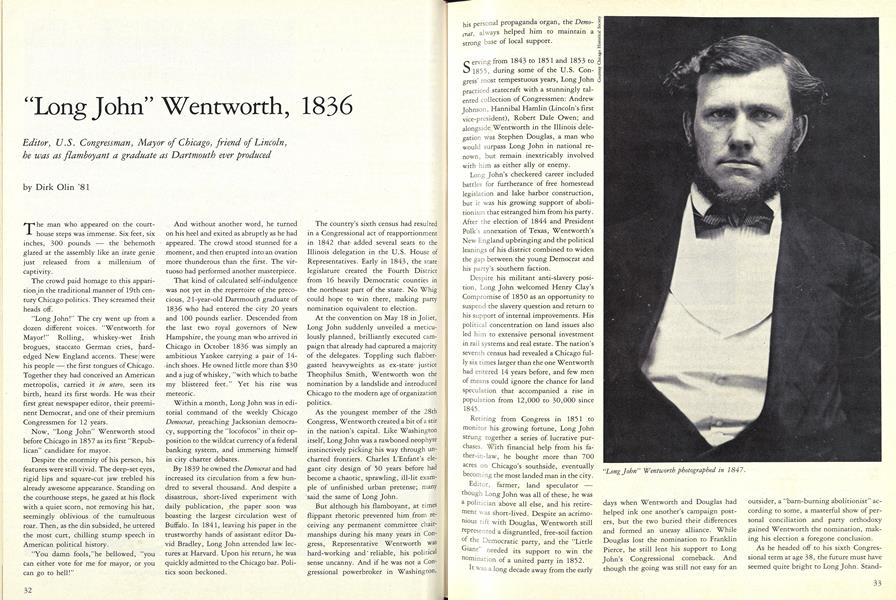

"Long John" Wentworth photographed in 1847.

Wentworth shown at Newcastle, N.H., in1884 with Mrs. Stiles Burton and her daughter Virginia.

Dirk Olin, a graduate of Northwestern University'sSchool ofJournalism, is in Washington on the staff ofthe Congressional Quarterly. As a sideline, he issecretary of the class of 1981.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureWhat Is Success?

March 1983 By E. R. (Skip) Sturman '70 -

Feature

FeatureYou know, what's his name . . ."

March 1983 By Nardi Reeder Campion -

Feature

FeatureOff and Chopping

March 1983 By Jean Hanff Korelitz -

Article

ArticleSetting the Record Straight: A Senior-Year Perspective

March 1983 By Libby Schmeltzer '83 -

Sports

SportsSports

March 1983 By Brad Hills '65 -

Article

ArticlePhilosopher Coach

March 1983 By Nancy Wasserman '77

Dirk Olin '81

-

Letters to the Editor

Letters to the EditorLETTERS

OCTOBER 1991 -

Article

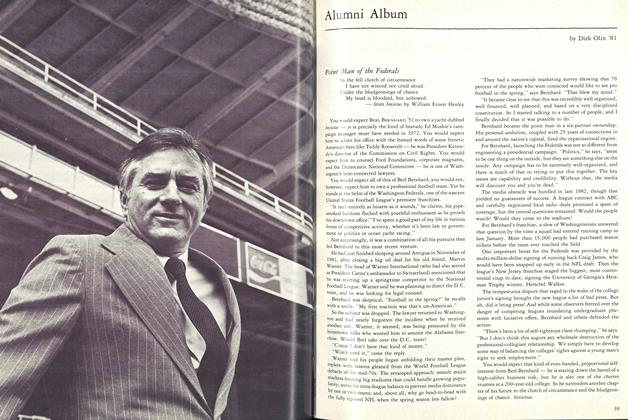

ArticleAlumni Album

APRIL 1983 By Dirk Olin '81 -

Article

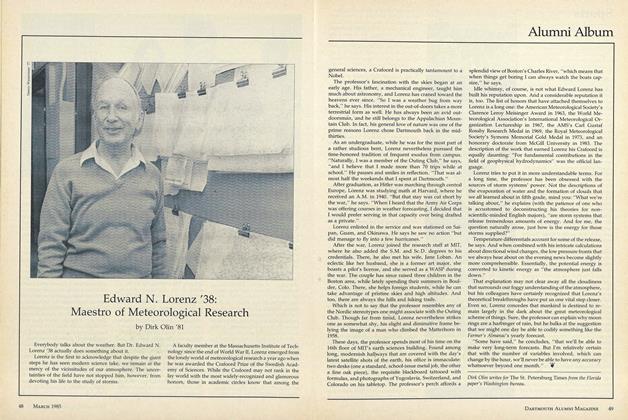

ArticleEdward N. Lorenz '38: Maestro of Meteorological Research

MARCH • 1985 By Dirk Olin '81 -

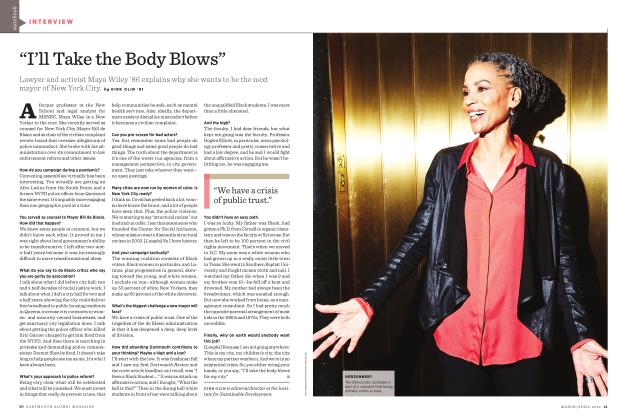

Interviews

Interviews“I’ll Take the Body Blows”

MARCH | APRIL 2021 By DIRK OLIN '81 -

Voices in the Wilderness

Voices in the WildernessOrder in the Court

SEPTEMBER | OCTOBER 2021 By Dirk Olin '81

Features

-

Feature

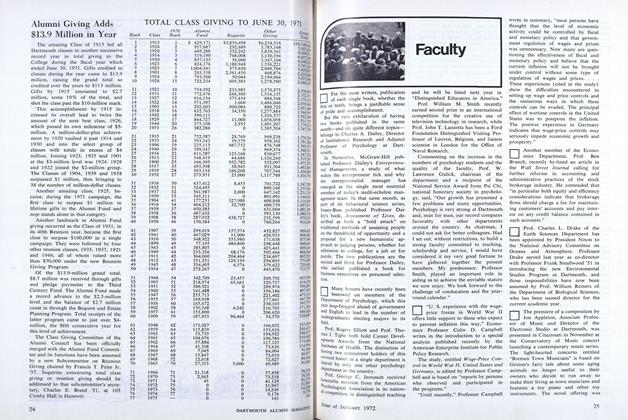

FeatureAlumni Giving Adds $13.9 Million in Year

JANUARY 1972 -

Feature

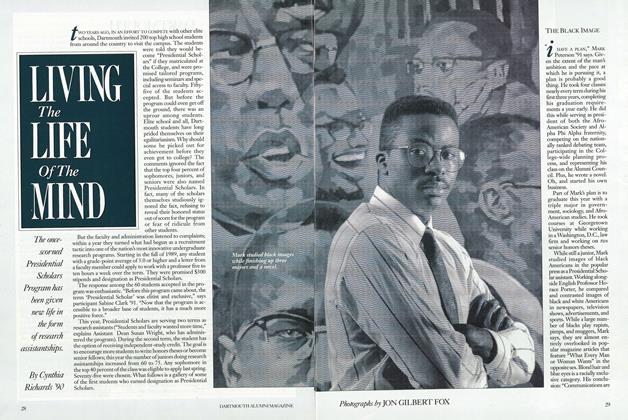

FeatureLIVING THE LIFE OF THE MIND

NOVEMBER 1990 By Cynthia Richards '90 -

Feature

FeatureBelieve It or Not!

October 1974 By GREGORY C. SCHWARZ -

Feature

FeatureOn a Freshman Trip, the Destination Is Community

MARCH 1989 By Jay Heinrichs -

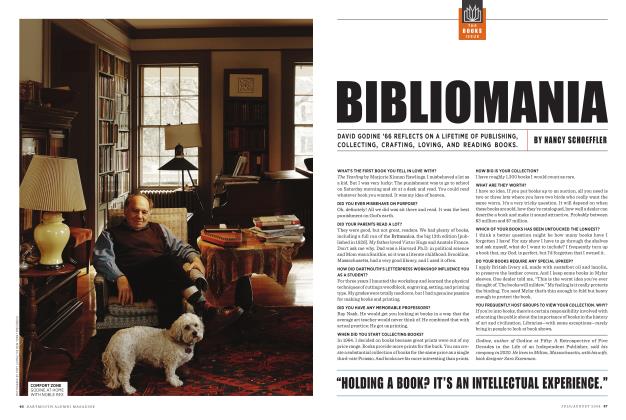

FEATURES

FEATURESBibliomania

JULY | AUGUST 2024 By NANCY SCHOEFFLER -

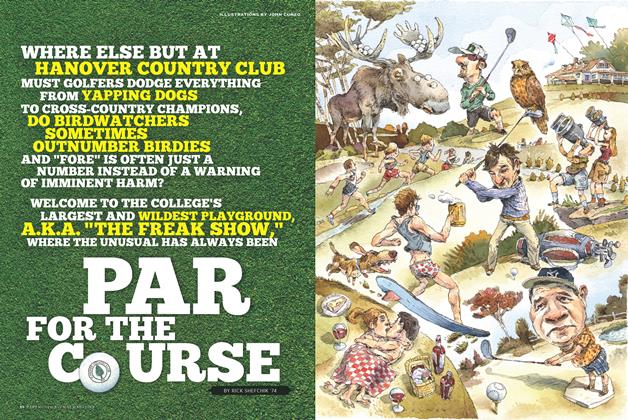

FEATURE

FEATUREPar for the Course

July | August 2014 By RICK SHEFCHIK ’74