"We fade in on the thin, clear, cold slope of the ski slide and fade through to the thin, clear, cold mind of a Dartmouth undergraduate." That is how Princetonian F. Scott Fitzgerald described Dartmouth men in filming directions for the movie 'Winter Carnival. This kind of erroneous thinking is commonly exercised by witless Princeton men, or, should I say, witlessly exercised by common Princeton men. In the three years that I have been working for the Dartmouth admissions office, I have heard many unthinking rumors concerning Dartmouth bandied about. Two are particularly persistent. The first, that Dartmouth is an Animal House. The second, that being in the backwoods of New Hampshire ensures a college life that is stultifying and provincial.

It is easier, of course, to refute the first assertion. In fact, five minutes at Dartmouth ought to erase any such fears easily. I was accepted to Dartmouth while the school was in the midst of an onslaught of pejorative press. Animal House had just been released and Esquire magazine had had a field day portraying the alleged caveman mentality of the Dartmouth student. As Animal House author Chris Miller told me when I interviewed him last year about the men of Phi Gam in 1963, "They were the sort of guys who swept the floor with their knuckles, in a simian sort of way." That was the impression the press was giving of all Dartmouth students, circa 1979.

At any rate, off I trundled, a nervous eighteen-year-old who had attended Madeira, a sheltered and relatively uneventful girls' school. Daddy packed up the cavernous Pontiac station wagon and we were off. I arrived a little before freshman week and drove up to Mid-Mass. There, draped across the stoop of the dorm, were eight massive Dartmouth animals. My first reaction was, "Daddy, turn the car around. We're going home." Having already paid my tuition, my father wouldn't turn the car around. As we started unloading, the eight sweaty beasts jumped up and with only a "May we help you, sir?" to my father, who was struggling under a refrigerator, promptly carried all my belongings to my new home. I later learned that I had arrived in the midst of football training and that the more moderately proportioned students had not yet arrived for freshman week and the fall term. So much for the Dartmouth animal! Needless to say, all Dartmouth students are not as mild as these athletic moving men. There are still wild parties and general carousing, but I scarcely think that it is significantly out of sync with other colleges in the coun- try (except maybe Harvard).

The second assertion is a little harder to put to rest, that Dartmouth students are not acquiring the sophistication and insight into society that they might be getting at a city school. It is impossible to say that we are missing nothing out in smalltown Hanover. There are few concerts, few professional plays, few museums. Any undergraduate can tell you there are no restaurants open past midnight. Also, no Bloomingdale's.

Be that as it may, what Dartmouth may lack in resources, it makes up in the comprehensive view it offers of a self-contained community. How can the Columbia student have an overall view of New York City, or even Morningside Heights? How can a Harvard student concentrate on courses and at the same time have any comprehensive view of all that's happening in Boston, Cambridge, or even Lowell House? But at Dartmouth things are different. We are able both to handle what professors teach us and keep up with what's happening in today's Dartmouth - even all of Hanover!

We can see how the community operates in parts and as a whole. In a city, events of everyday life tend to get obscured. A city becomes impersonal. At Dartmouth you see the most intense human instincts on the most intimate level. William Faulkner, in his Nobel Prize speech in 1950, said that in his fictional county could be seen "the old universal truths, lacking which, any story is ephemeral and doomed love and honor and pity and pride and compassion and sacrifice." Faulkner, one of the most insightful scribes of human drama, did not set his characters in Atlanta. He set them in a fictional locale resembling Oxford, Mississippi. Oxford is almost exactly the same size as Hanover.

Observant Dartmouth students learn the most important moral imperatives from firsthand experience. They are no longer abstract principles, but tangibles. More often than not, the results are gratifying. Only three weeks ago I was at war with Henry James. To be perfectly frank, I don't like Henry James very much, and the preparation of a 25-page paper on his late writing was almost unendurable. The ordeal was made bearable by the endless stream of visitors who came to interrupt and cheer me. During one study break, a friend commented that the best thing about Dartmouth was that at exam time, rather than undercutting each other, people at Dartmouth pulled together and supported each other. The small community fosters an affection among the Dartmouth family that I don't have to explain to any of you.

At Dartmouth, when something exciting happens, you know the cast of characters. When campus issues are discussed in newspapers, or on television, as they have been recently, the issues are not remote. They affect you personally ; if not you, then someone you know well. There are few matters that will not make some impact on your life.

Last Christmas, our family celebration was spent with Norwegian friends and relatives. On 60 Minutes the preceding Sunday, John Rassias, the flamboyant language professor, was featured. First impressions about this professor can be misleading. The Norwegians kept asking if I had had any courses with"the crazy professor"? No matter how hard I tried, I could not convince them that Professor Rassias was as sane as any of us, maybe saner and certainly cuter! To illustrate his kindness and rapport: one summer our overloaded station wagon was leaving town. As we were approaching the crossroads, the car was forced off the street by a man driving a truck, furiously waving his arms and shouting. He jumped out of the truck, came over to hug me good-bye, to ask whether I'd be back that fall, and to meet my parents. Never do I see Professor Rassias that he does not ask about my parents. And he demands that I bring them by for a visit when they are in Hanover. I would hardly expect this warmth and concern from one of the stars of Yale's galaxy.

If all this sounds a little Panglossian, I assure you that Dartmouth isn't always that wonderful. There are times when I have been cold, dismayed, and miserable. There are times when I have wanted to throw in my snowshoes and go home. I'm convinced that the voice crying in the wilderness was making an impassioned plea for central heating! I've had a crash course in deceit, treachery, and dishonesty. But aren't these the very things that life will present? It is true that these things may be harder to deal with in a small community where there is no anonymity behind which to hide, but, by the same token, the kindness that citizens show each other also lacks anonymity.

It's not just the big things like principles and snow that can make life difficult. Imagine having to move all your earthly possessions and change homes every ten weeks for three years. Imagine having an over-emotional roommate leaving suicide notes every other day! Imagine having sixteen bright-eyed freshmen counting on you, their undergraduate adviser, for advice during senior fall, when major career decisions are staring you in the face. Imagine returning to campus after six months at home and realizing that you have only three friends who aren't abroad or taking some internship in Jersey City or Kicking Horse, Montana. But each time you work some troublesome situation out, you've been involved with another slice of real life.

What I think will stand out most in my memory, as I join the ranks of Dartmouth alumni, is the academic opportunity I've been given. I was granted permission to take a special major in playwriting. I was allowed to design my own major from scratch. I was given the chance to do several independent studies. Through these courses, I was able not only to develop my interests and mold my curriculum, but also to work on a one-to-one basis with several brilliant professors. Last term, I did an independent reading program on Tennessee Williams with one of the most energetic and erudite members of the English Department. Each conference we would go for a walk around Hanover. Once we even went to West Leb for groceries. You have no idea how invigorating discussing Cat on a Hot Tin Roof in the frozen food aisle can be until you've tried it. This professor assumed an entire course load of work for himself, reading the minor works of Williams that I was reading. During our last meeting, the professor sat me down on a bench on Main Street and told me he hoped we'd keep in touch next term and continue what had developed into a friendship. This is not uncommon at Dartmouth.

Recently, a friend and I were having a cup of coffee at Lou's at about 9:30 one evening. As we got up to leave, I was stopped by two professors I knew. They invited me to join them and help to resolve an argument they were having about Wallace Stevens. I joined them and the three of us ended up talking about poetry, plays, and old movies until Lou's closed at midnight. One of the professors, under whose direction I wrote a full-length play, has become like a father away from home. He even scolds me when I don't wear my coat! It is this kind of interest by full professors that is exhilarating and unique to Dartmouth.

Sometimes, the closeness of life at Dartmouth seems overwhelming, and we get overdramatic. One Dartmouth student was denied valedictory honors. He tore up his diploma shortly after his graduation ceremony, exclaiming, "My industry may make me a great man, but this miserable parchment cannot!" Some time later, the same alumnus told the United States Supreme Court, "It's a small school yet there are those who love it." I'm not quite sure I understand why Daniel Webster got so upset and ripped up his diploma, but I do understand why most members of the Dartmouth family love this dear, small school in the wilderness.

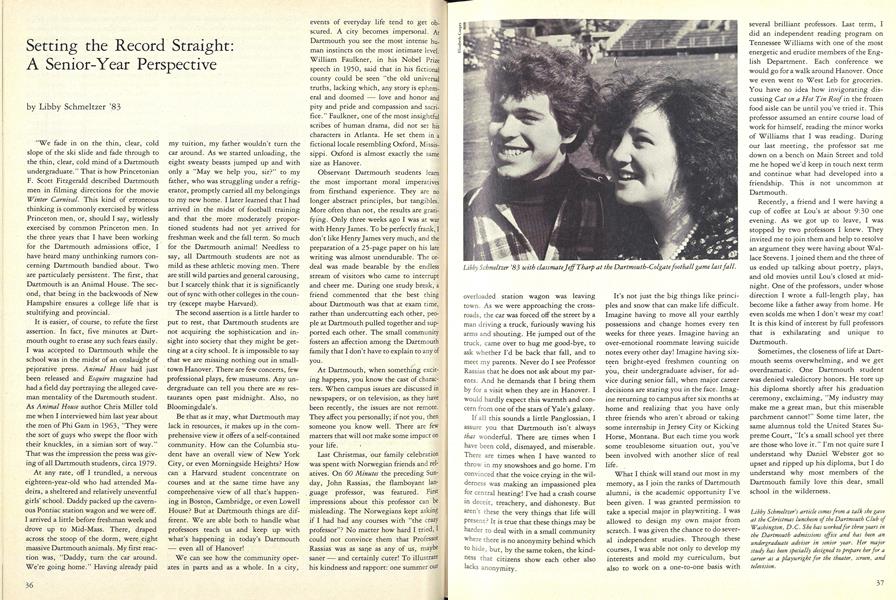

Libby Schmeltzer '83 with classmate JeffTharp at the Dartmouth-Colgate football game last fall.

Libby Schmeltzer's article comes from a talk she gaveat the Christmas luncheon of the Dartmouth Club ofWashington, D.C. She has worked for three years inthe Dartmouth admissions office and has been anundergraduate adviser in senior year. Her majorstudy has been specially designed to prepare her for acareer as a playwright for the theater, screen, andtelevision.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureWhat Is Success?

March 1983 By E. R. (Skip) Sturman '70 -

Feature

Feature"Long John" Wentworth, 1836

March 1983 By Dirk Olin '81 -

Feature

FeatureYou know, what's his name . . ."

March 1983 By Nardi Reeder Campion -

Feature

FeatureOff and Chopping

March 1983 By Jean Hanff Korelitz -

Sports

SportsSports

March 1983 By Brad Hills '65 -

Article

ArticlePhilosopher Coach

March 1983 By Nancy Wasserman '77

Article

-

Article

ArticleMr. Watson's article in this number of the MAGAZINE on "Americanism

April 1918 -

Article

ArticleQUARTER SYSTEM VS. SEMESTER

March 1919 -

Article

ArticleMasthead

December 1961 -

Article

ArticleLondon

FEBRUARY 1970 By FRED D. POLLARD '53 -

Article

ArticlePROFESSOR LORD'S HISTORY OF DARTMOUTH COLLEGE, 1815-1909*

March, 1914 By Herbert Darling Foster -

Article

ArticleTHE DARTMOUTH CAMPAIGNS FOR:

June 1931 By W. H. Ferry '32