PARADISE, a novel by Dikkon Eberhart '70 Stemmer House, 1983. 295 pp., $14.50

Paradise reworks and expands according to modern perceptions and preoccupations an early medieval taie, The Voyage of St.Brendan the Abbot. The novel is at least as distant from its source as Walt Disney's The Sword in the Stone is from Thomas Malory's Morte D'Arthur. Like the Arthurian legend, St. Brendan's adventures are a large fictional structure built on a slender factual foundation. Regarding the matter of Brendan itself, Admiral Morison, historian of American discovery and Mt. Desert Island, provides an accurate summary in his Northern Voyages (1971).

The plot of Paradise divides into a pro- logue and four parts. The four parts are two voyages and two land journeys. The prologue sets the scene on the Celtic fringe of the British Isles in the 6th century A.D. The novel's central figure, usually called Finbar, although he is North African rath- er than Irish, is shipwrecked on a small island and reduced to brutal subsistence. The first voyage of the tale begins when the crew of a curragh, an Irish leather boat, bound for Thule (Iceland), St. Brendan commanding, rescues Finbar.

Action is plentiful and cleanly told. The love scenes remind one of Ernest Hemingway in his middle period (e.g., For "Whomthe Bell Tolls) with a blasphemous dash of D. H. Lawrence thrown in.

The strongest element in the novel is the author's command of seascapes and the landscape of Maine. As these surroundings impress themselves on Finbar they tend to be strong and vivid: the desolate island where he fetches up, a hunting expedition with Atla, the ritual of small boat sailing (its splendid discomfort, enforced togetherness, long pains, sudden horrors, and inexplicable exhilarations). The companion pleasures of craftsmanship in curragh sailing and repair find equally apt expression as does the pleasant combination of awe and exercise that Finbar experiences trekking in Iceland. But Maine as a spiritual landscape dominates the book. As Finbar nears the Penobscot, sailing becomes smoother and descriptions take on the foggy hues and "American light" tints of the Luminist paintings that gave the coast of Maine to our national imagination and made Katahdin an icon of American nature. Possibly as a result of their edenic environment, the Abnaki are much more attractive than the Irish; they certainly run better clambakes. The author also seems more careful of Abnaki ethnography: he has the Irish providing their curragh with potato flour a millennium before Sir Walter Raleigh introduced the American tuber to the Old Sod. Finally, the evocation of the rain in Maine lends both mystery and accuracy to the journey up the Penobscot; the witches' sabbath on Katahdin is also suitably lurid in the best metaphysicalshocker style.

The cruise to Iceland is an agony beset by cold, wind, and whales. The next segment of the novel is a trek into central Iceland, led by Finbar and the most sympathetic of his shipmates, the abbess Ide. This is followed by a second voyage, a fine evocation of good sailing, a cruise by Finbar, Brendan, and three monks to Paradise. Eden, as it turns out, is Down East. The final, best section of the novel is a second trek up country: a forest journey through the Penobscot paradise to Mt. Katahdin. Guided by two Abnaki (Native American) medicine women, the band of seafarers, like hikers walking the length of the Appalachian Trail, anticipate a mystical experience on Katahdin. At the novel's climax, the party of clergy from two cul- tures and Finbar, a rough-and-ready au- thority on comparative religion, meet the supernatural equal parts of C. G. Jung and Carlos Castaneda above Milli- nocket. Two of the monks perish of the encounter: Joseph, a brother who is Nietzsche's model Christian, an ascetic bundle of resentments, dies badly; Bar- inth, an elderly Christian shaman who talks to whales, dies well. Finbar abandons metaphysical questing and settles down to a life as a clergy-woman's husband and smith among the Abnaki. Brendan, cheerful and tolerant but a bit of a Captain Ahab, and his remaining crewman, the sportsman-monk Atla, sail off into the sunrise.

Otherwise, metaphysics is the novel's least happy ingredient. As his anachronis- tic interest in steel forging and his the- ological slang remind us, Finbar is a mod- ern, post-Christian man acting against a proto-Christian stage-set. The god whom Finbar finds wanting has had to weather the Reformation and the Enlightenment. Finbar's critique combines Protestant ar- guments against "charnel worship" with Enlightened defence of noble savagery. This leads to a shifting double standard of divinity: if "Cautantowit" (the Abnaki manitou) "is Cautantowit, not man, not woman" (p. 218), why can't Jehovah (at very least the Jewish manitou) be Jehovah rather than "a sexless man" (p. 220). A real conversation about the (in)compabilities of revealed and natural religion would have cleared up these inconsistencies. It is a muddle. Finbar, who likes to think of himself as a simple smith, and the Irish, for various reasons, can't get out of it. Brendan and Atla aren't interested; Barinth is senile; Joseph is neurotic; for Ide, sex gets in the way. Perhaps that is Mr. Eberhart's point: modern people have become too muddled to ask the god-question in a vocabulary that can hope for an answer.

History, in any event, writes an ironic footnote to the religious aspect of a fictional imagining of monks in Abnaki Maine: the Abnaki converted quickly to Christianity as preached to them by celibate religious in the 17th century. The sad epic of mutual loyalty between Abnaki and Jesuit awaits its modern novelist. In the meantime we have Paradise, a fine novel of small boat sailing and wilderness trekking that the likes of John Ledyard, Class of 1776, for example, would read with interest and enjoyment.

Dr. Meier, who retains his undergraduate interest in medieval studies, has recently left aposition in the pathology departynent at theDartmouth Medical School to take up a post atthe University of Utah Medical Center in SaltLake City, much further than he likes to be fromPenobscot Bay.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

Feature"Ladieees and Gentlemen.

September 1983 By Jim Tonkovich '68 -

Feature

FeatureShaping Up

September 1983 By Shelby Grantham -

Cover Story

Cover StoryThe Dartmouth Disease

September 1983 By George O'Connell -

Feature

FeatureA VETERAN MOVES ON

September 1983 By Brad Hills '65 -

Feature

Feature"Those Who Miss The Joy, Miss All"

September 1983 By Nardi Reeder Campion -

Feature

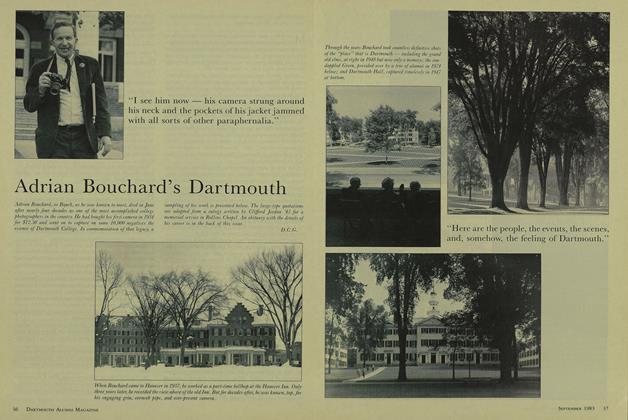

FeatureAdrian Bouchard's Dartmouth

September 1983 By D.C.G.

Books

-

Books

BooksFaculty Publications

February 1934 -

Books

BooksFRONTIER OHIO

May 1936 By Allen R. Foley '20 -

Books

BooksESSAYS ON CATHOLIC EDUCATION IN THE UNITED STATES

June 1942 By Howard F. Dunham '11 -

Books

BooksNEWMAN: THE CONTEMPLATION OF MIND.

APRIL 1971 By LOUIS L. CORNELL -

Books

BooksDISCOVERY: THE AUTOBIOGRAPHY OF VILHJALMUR STEFANSSON.

OCTOBER 1964 By RICHARD W. MORIN '24 -

Books

BooksE. E. CUMMINGS.

JULY 1964 By THOMAS VANCE