The year is 1953. John Crawford Woodhouse, Dartmouth '21, is on a railroad train sitting with three famous nuclear physicists who are returning to Los Alamos to continue work on the hydrogen bomb. One of them says they are not making any progress on the bomb because the process of liquifying tritium resulted in a device that was unusable because of its enormous size. John Woodhouse suggests they react tritium with lithium 6 to make a solid compound.

Nuclear Physicist: "Impossible. You know you can not separate lithium 6 and lithium 7."

Woodhouse: "It's already been done. Look in Volume One of Sidgwick's Chemical Elements. In a footnote at the bottom of page 61, G.N. Lewis tells how he did it before 1936."

One week later John Woodhouse received a postcard with this cryptic message: "Dear John, today we crossed the Rubicon. We are going to use your compound. Signed, J.W., E.G.W., and E.T."

"Wasn't my compound," says John Woodhouse, whose ego seems to be in balance. "It was G.N. Lewis's compound."

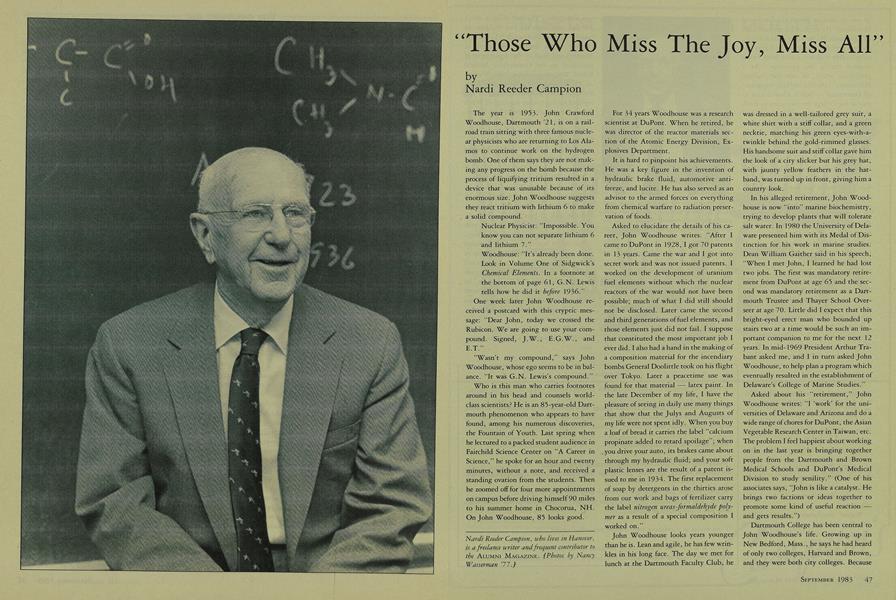

Who is this man who carries footnotes around in his head and counsels worldclass scientists? He is an 85-year-old Dartmouth phenomenon who appears to have found, among his numerous discoveries, the Fountain of Youth. Last spring when he lectured to a packed student audience in Fairchild Science Center on "A Career in Science," he spoke for an hour and twenty minutes, without a note, and received a standing ovation from the students. Then he zoomed off for four more appointments on campus before driving himself 90 miles to his summer home in Chocorua, NH. On John Woodhouse, 85 looks good.

For 34 years Woodhouse was a research scientist at DuPont. When he retired, he was director of the reactor materials section of the Atomic Energy Division, Explosives Department.

It is hard to pinpoint his achievements. He was a key figure in the invention of hydraulic brake fluid, automotive antifreeze, and lucite. He has also served as an advisor to the armed forces on everything from chemical warfare to radiation preservation of foods.

Asked to elucidate the details of his career, John Woodhouse writes: "After I came to DuPont in 1928, I got 70 patents in 13 years. Came the war and I got into secret work and was not issued patents. I worked on the development of uranium fuel elements without which the nuclear reactors of the war would not have been possible; much of what I did still should not be disclosed. Later came the second and third generations of fuel elements, and those elements just did not fail. I suppose that constituted the most important job I ever did. I also had a hand in the making of a composition material for the incendiary bombs General Doolittle took on his flight over Tokyo. Later a peacetime use was found for that material latex paint. In the late December of my life, I have the pleasure of seeing in daily use many things that show that the Julys and Augusts of my life were not spent idly. When you buy a loaf of bread it carries the label "calcium propinate added to retard spoilage"; when you drive your auto, its brakes came about through my hydraulic fluid; and your soft plastic lenses are the result of a patent issued to me in 1934. The first replacement of soap by detergents in the thirties arose from our work and bags of fertilizer carry the label nitrogen ureas-formaldehyde polymer as a result of a special composition I worked on."

John Woodhouse looks years younger than he is. Lean and agile, he has few wrinkles in his long face. The day we met for lunch at the Dartmouth Faculty Club, he was dressed in a well-tailored grey suit, a white shirt with a stiff collar, and a green necktie, matching his green eyes-with-atwinkle behind the gold-rimmed glasses. His handsome suit and stiff collar gave him the look of a city slicker but his grey hat, with jaunty yellow feathers in the hatband, was turned up in front, giving him a country look.

In his alleged retirement, John Woodhouse is now "into" marine biochemistry, trying to develop plants that will tolerate salt water. In 1980 the University of Delaware presented him with its Medal of Distinction for his work in marine studies. Dean William Gaither said in his speech, "When I met John, I learned he had lost two jobs. The first was mandatory retirement from DuPont at age 65 and the second was mandatory retirement as a Dartmouth Trustee and Thayer School Overseer at age 70. Little did I expect that this bright-eyed erect man who bounded up stairs two at a time would be such an important companion to me for the next 12 years. In mid-1969 President Arthur Trabant asked me, and I in turn asked John Woodhouse, to help plan a program which eventually resulted in the establishment of Delaware's College of Marine Studies."

Asked about his "retirement," John Woodhouse writes: "I 'work' for the universities of Delaware and Arizona and do a wide range of chores for DuPont, the Asian Vegetable Research Center in Taiwan, etc. The problem I feel happiest about working on in the last year is bringing together people from the Dartmouth and Brown Medical Schools and DuPont's Medical Division to study senility." (One of his associates says, "John is like a catalyst. He brings two factions or ideas together to promote some kind of useful reaction and gets results.")

Dartmouth College has been central to John Woodhouse's life. Growing up in New Bedford, Mass., he says he had heard of only two colleges, Harvard and Brown, and they were both city colleges. Because he was an outdoor person, he discovered Dartmouth. He worked his way through college, made Phi Beta Kappa as a junior, and was president of Alpha Chi Sigma fraternity. (He still has a scar from being branded during the initiation.) As a graduating senior, he won the DuPont Fellowship the first and only one granted Dartmouth which allowed him to stay at the College for two years to teach chemistry. And at Harvard he was elected to the Sigma Psi honor society for scientists. After Commencement exercises in 1921, President Hopkins made a remark that made a life-long impression on John Woodhouse. "Gentlemen, you are going into a variety of professions. I believe Dartmouth has trained you well and you will be successful. But if you don't make a substantial contribution to your community _ be it a crossroads in Vermont or New York City you will be a failure." Woodhouse took Hoppy s advice to heart; he wrote in his class's 60th reunion newsletter: "My vocation was science chemistry, biology, nuclear areas, and marine science but my avocation has been public service. ..."

With an M.A. from Dartmouth and an M.S. from Harvard, Woodhouse received his doctorate in chemistry from Harvard in 1927. Two professors stand out in his memory: Dartmouth's Bobby Bartlett who told him, "To get results, you have to work five times, ten times faster"; and Harvard's Arthur Lamb who said, "Never worry about violating a theory. Theories are just for teaching. Go ahead and do experiments."

John Woodhouse has served Dartmouth in many capacities, as Trustee of the College from 1960 to 1968, as Overseer of Thayer, as vice president of the Alumni Council, and as president of the Delaware Dartmouth Club. In 1957 he was given the Alumni Award.

Dartmouth people consider him unique.

Ad Winship '42: "John is a Yankee mountain man, a spartan in speech. Doesn't say much until he has something to say. But like still waters, he does indeed run deep."

Walter Stockmayer h '83: "John Woodhouse has an usual combination of talents. Some more academic scientists don't see the practical soon enough. Others, more practical, don't appreciate pure science. Woodhouse understands both sides. He has always made sure there are human stakes involved in chemistry."

Ort Hicks '21: "He personifies the Robert Louis Stevenson sentence that President Hopkins always quoted about education: Those who miss the joy, miss all.' John has gotten the joy of life into everything he does and he can transmit that joy to others."

Fifty-six years ago, John Woodhouse married Ann Hurth in New Bedford. He says with pride, "The best thing in Ann's life and mine were the two children we raised." Robert, Dartmouth '51, is a psychiatrist at the Institute for Living in Hartford and head of the department of psychiatry at the Connecticut Medical School. Their younger son, John, Wesleyan '53, has long been a Wesleyan trustee. He is president of Sysco in Houston and replaced his father some years ago in Who'sWho, a tome which has had a John Woodhouse in it for over 35 years.

Now a widower, Woodhouse divides his time between Wilmington and Chocorua. He is active in the Presbyterian church and is a Republican. His hobbies include mountain climbing, hunting, freshwater fishing, canoeing, classical music, and traveling from Tierra Del Fuego to Alaska. He enjoys life to the hilt but he does dislike eating alone. Asked about his faults he says, "I have lots. Stubborness, for instance." Like most people born with drive, he is not famous for his flexibility.

Last fall he was sitting on his screened porch enjoying the view when a group of young people with back packs knocked and asked him to direct them to the path up Mount Chocorua. "Wait a minute," he said, "I can do better than that." He went inside and put on his hiking shoes. Then he said, "Just follow me up the mountain. I'll show you the way."

For 85 years (and counting), John Woodhouse has shown a lot of people the way.

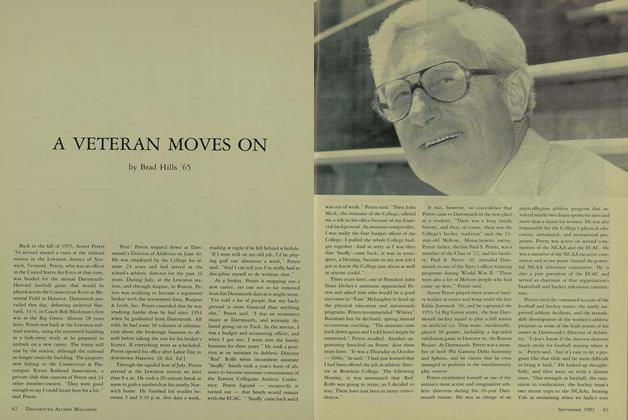

Those figures on the blackboard mean something, as John Woodhouse '21 told a very interested group of Dartmouth students earlier thisspring. Not bad, college lecturing that is, at theage of 85.

Nardi Reeder Campion, who lives in Hanover,is a freelance writer and frequent contributor tothe ALUMNI MAGAZINE. {Photos by NancyWasserman '77.}

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

Feature"Ladieees and Gentlemen.

September 1983 By Jim Tonkovich '68 -

Feature

FeatureShaping Up

September 1983 By Shelby Grantham -

Cover Story

Cover StoryThe Dartmouth Disease

September 1983 By George O'Connell -

Feature

FeatureA VETERAN MOVES ON

September 1983 By Brad Hills '65 -

Feature

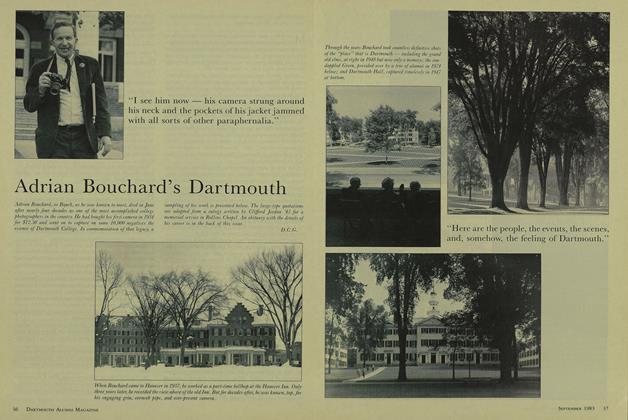

FeatureAdrian Bouchard's Dartmouth

September 1983 By D.C.G. -

Class Notes

Class Notes1958

September 1983 By Fred Louis III

Nardi Reeder Campion

-

Letters to the Editor

Letters to the EditorLetters to the Editor

December 1978 -

Article

Article'Most Improved Professor'

December 1978 By NARDI REEDER CAMPION -

Article

ArticlePolyglot Son of Polyglots

October 1979 By NARDI REEDER CAMPION -

Cover Story

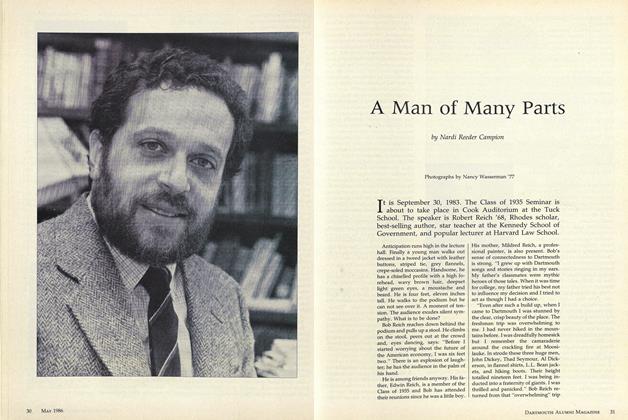

Cover StoryA Man of Many Parts

MAY 1986 By Nardi Reeder Campion -

Cover Story

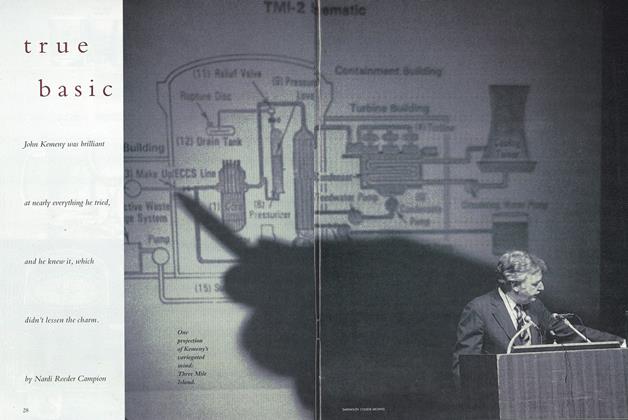

Cover StoryTrue Basic

May 1993 By Nardi Reeder Campion -

Article

ArticleJody's PALS Sing Out

NOVEMBER 1999 By Nardi Reeder Campion

Features

-

Feature

FeatureThird Century Fund Launches General Campaign Among Alumni

OCTOBER 1969 -

Feature

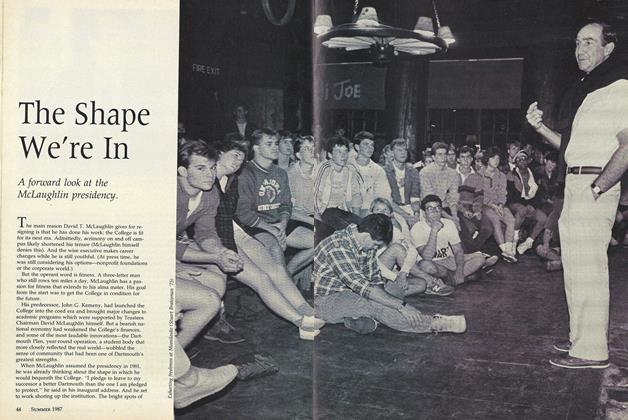

FeatureThe Shape We're In

June 1987 -

Feature

Feature5. Residential Life

December 1987 -

Feature

FeatureJames Marsh, Dartmouth, and American Transcendentalism

MARCH 1969 By Douglas M. Greenwood '66 -

Feature

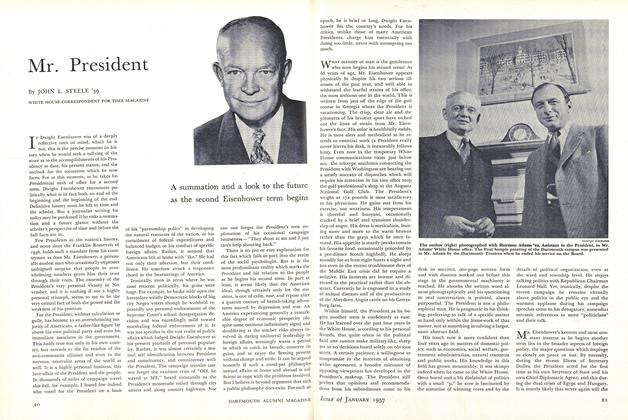

FeatureMr. President

January 1957 By JOHN L. STEELE '39 -

Cover Story

Cover StoryRousseau Cops an Exam

MARCH 1995 By Philippa M. Guthrie '82