"You spend four years trying to get out of this place, and the rest of your life trying to get back."

I was a bit puzzled (but flattered too, I suppose) when I found myself at the head table for the big annual dinner of the Dartmouth Alumni Association of Greater Boston in the late 19505. It was an honor, obviously, because the Boston dinner is THE BIG ONE on the alumni circuit and Hanover heavyweights sat elbow to elbow with Trustees, club presidents, etc.

I was puzzled because I was not an alumnus, or even a distinguished faculty member being showcased. What I was was a newly recruited director of the Dartmouth News Service and pretty far down in the Hanover administration's pecking order.

Looking back I consider that evening the start of my efforts to understand the Dartmouth Disease. It continues to this day. I probably understand it better now but not completely.

What is the Dartmouth Disease? In the College's official publications it is often referred to as the Dartmouth Fellowship, the Dartmouth Family, the Dartmouth experience, or some such vague or vapid term. Dartmouth's detractors usually envious alumni of other institutions, or wives who feel neglected when hubby devotes family-time hours on Dartmouth's behalf often call it the Dartmouth Syndrome or the Dartmouth Religion, and in its grossest form they might refer to it as Big Greenerism or even Animal Housism.

But to get back to the Boston dinner and perhaps illustrate a point: The evening's emcee gaveled for quiet without notable success. The cocktail hour had stretched into the usual two, and the convival chatter and clatter of removing dishes continued as he began the post-dinner introductions of the head table. "On my extreme right, Jim Such-and-such, Class of Whatever, president of the So-and-so Club. Stand up, bow, and sit to faint applause from a few classmates, fellow club members, and maybe a brother-in-law, but with little change in the noise level. Then, "And next to him, George O'Connell, Class of '45, University of Montana???" The question marks indicate the rising inflection at the end. Removing his reading glasses and raising his eyebrows, he seemed to glare my way. "Who goofed? What's this turkey doing here?" A hush fell over that vast dining room and I swear that 500 pairs of eyes focused on me as I did a quick up-and-down. Whether they were curious or hostile I couldn't tell. But Yassir Arafat couldn't have felt more out of place at a banquet of the American Jewish Committee. Patently, I was an intruder, an outsider. I sensed that a faculty member from Y-H-P or other highly respected schools might be tolerated, if not embraced, but I was a keeper of the flame as director of the News Service (a gussified name for a public relations function).

Over the ensuing 10 years in Hanover I had opportunities to observe the Dartmouth Disease closely, usually with wonderment and not a little awe. I have no social science statistics or data to back me up; just some journalistic impressions that I will share with you.

Why That was the nagging question that I kept asking myself as I observed the manifestations of the Dartmouth Disease. Why would otherwise rational, unemotional achievers get weepy at the sight of Dartmouth Row and spend countless hours and considerable energy serving as fund-raisers, student recruiters, club organizers, and writers of letters to the ALUMNI MAGAZINE? Reason told me that they couldn't all be insurance or bond salesmen trying to make business contacts. And even a cursory examination indicated that the busiest and most successful ones gave most of themselves.

I should explain that I came to Hanover from 10 years of newspapering. Dealing with politicians, space-grabbing promoters, and ego-tripping publicity seekers, one develops a certain cynicism about motives. My own war-interrupted college years at the universities of Montana and Washington and at Carroll College hadn't prepared me for Dartmouth. Now I have a great love for and pride in my native state of Montana (Montanans are often said to be modest Texans), but I don't really have any deep feeling for my alma, mater or maters. Maybe those institutions sensed it because I don't recall that they were ever in touch, even for a contribution. On the other hand, probably none had an alumni-records keeper like the tenacious Charlotte Ford Morrison to track me down or a Sid Hayward, Ort Hicks, George Colton, or Cliff Jordan to remind me of my duty as a alumnus. But then I didn't volunteer the information either.

The earliest intimation I had came in the first week or so on the job. I read a reprint of a DARTMOUTH ALUMNI MAGAZINE article by the brilliant satirist-parodist Corey Ford entitled if faulty memory serves "Can I Get In?" A Columbia alumnus, Corey had taken up residence in Hanover partly because of the excellent fishing and hunting the region offered, but he soon became involved in College life as "coach" of the Rugby Club (a title he relished even as he acknowledged that he could barely distinguish a line-out from a scrum) and as an unofficial adviser to various student publications.

In the article he pleaded earnestly, but humorously, to be admitted to the Dartmouth Fellowship. I assumed that he was satirizing the phenomenon until I met him. It turned out that he was deadly serious at least as serious as Corey ever was.

He told me that after considerble deliberation, examination of credentials, character references, and a searching evaluation of how he treated his dogs, he was enrolled as an honorary member of the Class of '2 1.

After some months of puzzling, I sought out Don Morrison, then provost of the college and a brilliant educator. I had learned that he, too, was a state university alumnus (West Virginia, but with a Princeton doctorate), so he should have some special perceptions.

Why, I asked, do Dartmouth alumni behave as they do? Why this deep loyalty and involvement in the College's activities? "Because it's expected of them," he replied.

In that terse and somewhat cryptic response he revealed a whole theory of education that I didn't really appreciate-fully until later. Expect even demand a high level of effort and achievement of students and alumni and they will respond. It works with kids too, as we are only now rediscovering; kids can learn, can do homework assignments and can even clean up their rooms, if it is expected of them. And habits developed in schools can be expected to carry over to adult years.

T7 ven as I continued to puzzle about this strange new world, I was named Dartmouth's representative to the Ivy League Public Relations Committee. This would be a chance, I reasoned, to indulge in comparative studies. Were other similar schools accorded the same reverence and loyalty? At the first gathering I attended, I was welcomed by the current chairman with a childish riddle. "Do you know why so many Dartmouths join the Marine Corps?" No, why? "So they can continue to wear green underwear." Ha, ha. It was not an inspiring introduction to this group of image-makers of exalted institutions.

I soon learned that the Ivy brethren had refined one-upsmanship and snide putdowns to nearly an art form. The trick was to affect a certain insouciance, but to steer the discussions to topics that revealed your school's strength. But it couldn't be done directly, as in, "Hey, did you hear about the grant we got from the Ford Foundation?" How gauche! No, it had to be done by indirection and anecdotally. Harvard's representative, for instance, might mention the eccentricities of the institution's latest Nobel Prize winner as he was being interviewed by a TimeMagazine reporter; Cornell liked to drag in a mention of radio telescopes and exploration of space, but shuddered when agriculture or hotel management were mentioned; Princeton savored opportunities to discuss SAT scores of entering classes.

I searched for an appropriate opening to discuss Alumni Fund participation, and being an avid sports fan, ways to broach sports results. About this time Bob Blackman was working his Ole Black Magic in football, "Doggie" Julian had Rudy Laßusso and Dave Gavitt in basketball, and Eddie Jeremiah's hockey teams were terrorizing the League. Nobody allowed me an appropriate opening. Indeed, such non-intellectual pursuits were unworthy of serious discussion, it was implied. I was at something of a loss until our luncheon speaker, Dean Edward Barrett of the Colum- bus School of Journalism gave me an opening.

Before launching into his presentation, he looked around and asked: "Where is the Dartmouth representative?" I raised my hand. "Do you have any more up there like Chris Wren?" he asked. (Wren '57 later graduated with honors and is now Beijing bureau chief for the New York-Times.) "Quite a few," I replied nonchalantly. "I'll send you a list." It was probably my finest hour at the Ivy Flacks meetings.

Most alumni must mingle and speak to non-Dartmouths the course of their business and social lives. Many have told me that a similar attitude often prevails and some have developed ripostes, rejoinders, etc. It's a good idea to rehearse a few and await the proper time, but the most effective way is to have someone feed you a line, as Dean Barrett did.

A little later I was issued one of those green (what else?) permanent name tags to wear on my jacket pocket at various college functions. It replaced the temporary paper ones that had to be lettered each time. I sensed than that I had made the team. But that created problems, too. Often when I was introduced at some function or other, the introducee's eyes would dart to my name tag and he would ask quizzically, "What class were you?" The trouble was there wefe no numbers after my name and he would assume that this was an oversight. "I'm not Dartmouth." Usually that was enough to send the questioner off to seek more compatible company. But a few hardy souls persisted. "Don't tell me you're a Yalie?" "No. "."Not a Harvard," in horror. "No, University of Montana." That was enough to send them back to the bar for a refill.

From time to time, President John Sloan Dickey '29 tried to explain the Dartmouth Disease, but never to my complete satisfaction. As a victim, he knew the symptoms, but was a bit shaky about the causes. However, he often talked of the special fellowship that a relatively small, isolated campus can engender. Students and faculty mingle, there are few outside distractions, and the campus is the focus of virtually all activities. Then, too, there is the sheer beauty of the place. The campus itself with its gleaming buildings, the surrounding mountains, the Connecticut River, the Main Street shops. The place, of course, is important in considering the root causes of the Disease.

Dean Douglas Horton of the Harvard Divinity School was the commencement speaker at one of the first Dartmouth commencements I was involved in, and he took the "place" concept a step further. In a speech entitled "A Return to the Sources," he postulated that that just as Jesus Christ gained strength to face his ordeal by spending 40 days in the desert, so alumni return in record numbers to reunions or on vacations and seek out any excuse to come to Hanover, to return to the sources of their development into adults. Nostalgia, sighing for a lost youth. Maybe they are factors, too, and I accept them as valid. But the aspect that I remember best is the people. A few vignettes may illustrate.

A non-alumnus faculty member who had' been reared in a tough section of the Bronx told me: "I'm a little worried about my kids. People here are too nice. When the kids get out into the outside world they may be in for some rude shocks."

He was right in some ways, I suppose, but I found that leaving Hanover didn't end the connection and that Dartmouth people can be nice, no matter where. When we moved to New York's Westchester County, a new neighbor (an alumnus) appeared at our door to welcome us. He had heard via some mysterious grapevine of our arrival. When he found that our household goods had been delayed en route, he invited all six of us to dinner and provided cots, sleeping bags, pots and pans, and so on. Thus we survived until our stuff arrived. We had a pre-dinner libation in his den and I found that it contained every conceivable bit of Dartmouth memorabilia banners, framed pictures of Baker, Dartmouth Row, and the Bema, Dartmouth chairs, etc. His wife told me, "I make him keep all this junk in here; I don't want it cluttering up the rest of the house." But she said it lovingly and tousled his hair.

An alumnus who was applying for a Dartmouth job told me: "You spend four years trying to get out of this place and the rest of your life trying to get back." That may explain why so many alumni are choosing Hanover and environs as their retirement homes.

When my wife was hospitalized for an extended period, the whole Hanover community seemed to rally round and offered sympathy, support, and casseroles.

By now you've probably guessed that I am a victim of a variation of the Dartmouth Disease. It's true, but I'm not alone as a non-alumnus. It afflicts many faculty (especially the tenured ones) and I suppose President emeritus John Kemeny (Princeton '47) is a leading exemplar, second only to beautiful wife Jean (Smith '53). On the same plateau were Dean Joe McDonald (Indiana University ' 15) and Warner Bentley (Pomona '26), the Hopkins Center's guiding genius.

Apparently, though, it's not hereditary. Eldest son Vincent was a three-sport star in high school and an Ivy-worthy student. He was actively recruited by many highly selective colleges and father and son enjoyed their hospitality at dinners, campus visits, etc. His choice would obviously be Dartmouth.

Alas, he chose Brown and explained, "Dad, I love Dartmouth and I always will, but I need a different experience." I accepted his decision. Reluctantly, I might add, because it ended my dream of frequent visits to Hanover, ostensibly to see him, but with some other motives too. Brown? All I could think of was Providence, a place with all the disadvantages of a metropolitan area and not many of the advantages.

And then came the final "Who-do-you-cheer-for?" schizophrenia. I watched as Vince fullbacked the Brown rugby team that defeated Dartmouth and went on to win the Ivy Championship.

I've worked my way through the Dartmouth Disease concepts of John Dickey (place, proximity, etc.) and Dean Horton (returning to the sources) and even added one of my own the people.

But I'm still questing and questioning. Now if someone out there knows of a foundation or an individual that would like a more thorough study of the Dartmouth Disease, my number is in the phone book.

Why would otherwise rational,unemotional achievers get weepy at the sightof Dartmouth Row, and spend countlesshours and considerable energy serving asfund-raisers, student recruiters, cluborganizers, and writers of letters to theALUMNI MAGAZINE?

From time to time, President John SloanDickey tried to explain the DartmouthDisease, but never to my completesatisfaction. As a victim, he knew thesymptoms, but was a bit shaky\ about thecauses.

George O'Connell '45 (University of Montana), was News Director atDartmouth from 1957—1967. He manages to get back to Hanover atleast once a year whether he needs to or not.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

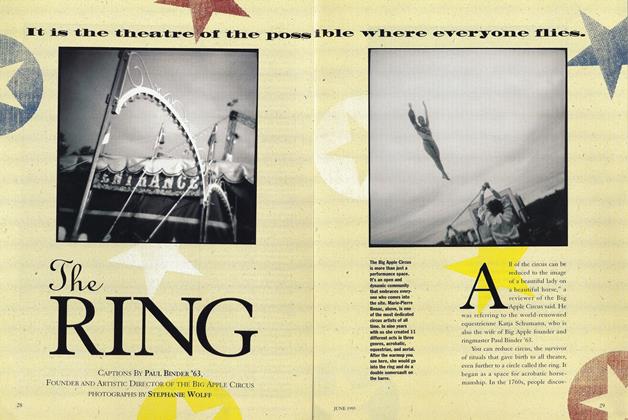

Feature"Ladieees and Gentlemen.

September 1983 By Jim Tonkovich '68 -

Feature

FeatureShaping Up

September 1983 By Shelby Grantham -

Feature

FeatureA VETERAN MOVES ON

September 1983 By Brad Hills '65 -

Feature

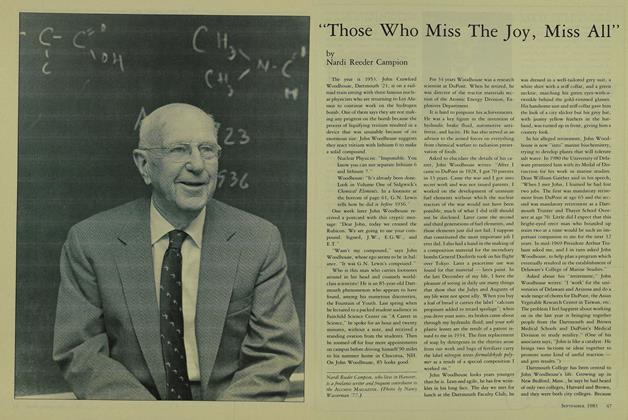

Feature"Those Who Miss The Joy, Miss All"

September 1983 By Nardi Reeder Campion -

Feature

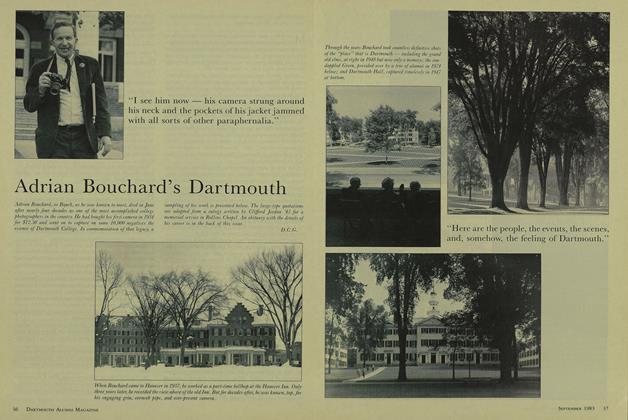

FeatureAdrian Bouchard's Dartmouth

September 1983 By D.C.G. -

Class Notes

Class Notes1958

September 1983 By Fred Louis III

George O'Connell

-

Feature

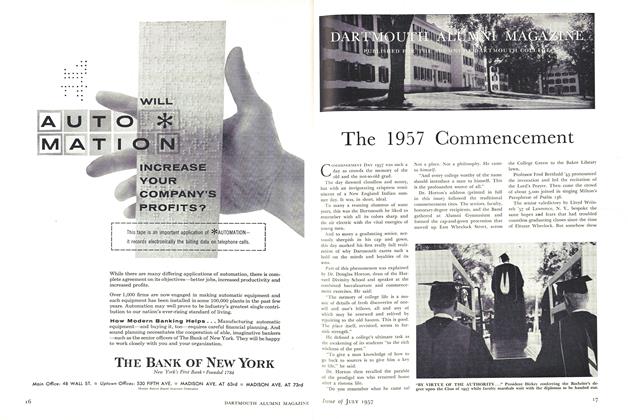

FeatureThe 1957 Commencement

July 1957 By GEORGE O'CONNELL -

Feature

FeatureThe 190th Commencement

JULY 1959 By GEORGE O'CONNELL -

Article

ArticleTHE FACULTY

November 1961 By GEORGE O'CONNELL -

Article

ArticleTHE FACULTY

June 1962 By GEORGE O'CONNELL -

Article

ArticleThe Faculty

OCTOBER 1965 By GEORGE O'CONNELL -

Feature

Feature"The Computer Revolution" Revisited

OCTOBER 1984 By George O'Connell