A lot of gold medals were won by Americans this summer in the 23rd Olympics in Los Angeles. Some say the athletes had an easy time of it, without the fierce Communist-bloc competitors and with the home-country advantage. If the 1912 games had been played in this country, Harry T. Worthington '17, the oldest living former Olympian, might have had a better chance at winning a medal.

His sport was the broad jump, now known as the long jump. His nemesis was the tenday ocean crossing on the SS Bolton Finland, which carried the American team to the games in Sweden in 1912. Because of the recent tragic fate of the Titanic, the Bolton Finland was diverted to a southern route, which took twice as long to complete. But whether the trip had lasted five days or ten, Worthing ton would have been seasick all the way.

Worthing ton, the youngest member of the American team and a student at Phillips Exeter Academy, had never been on a boat before. He was impressed by, but unable to take much advantage of, the training facilities set up on one side of the ship where sprinters and jumpers and vaulters ran the straight away or in the gym below decks where the athletes worked out.

In a recent interview with Long Island Newsday, Worthington discussed some of the team's stars. "Was he an athlete!" he said of the legendary Jim Thorpe. "Such a marvelous build." He was also impressed by Duke Kahanamoku, who went on to win the 100 meter freestyle that year and again in 1920. Kahanamoku was also one of the early athletes to capitalize on his celebrity, putting his name on a line of colorful floral clothes and swimsuits and eventually becoming mayor of Honolulu.

The opening ceremony for this year's Olympics was "pure Hollywood," according to one reviewer. More than 80 grand pianos, a 750-piece marching band, and 1,200 heliumfilled balloons thrilled an audience of 90,000 as the 7,800 athletes marched in. In 1912, things were much simpler. "It was straight pure amateur competition," said Worthing ton. "The teams (comprising some 2,000 athletes) marched in and saluted the King of Sweden." But it was elaborate enough for the prep school student from New Hampshire. Participating in the Olympics had been a dream of his for a long time.

He had become the national champion in the "running broad jump" while a student at Phillips Exeter and subsequently was asked by the Boston Athletic Association to represent it at the Olympic tryouts where he qualified for the American team.

But after ten energy-depleting days at sea, his performance in his own event in Stockholm was disappointing, he told Newsday. Albert Gutterson, whom Worthing ton had beaten at the Olympic trials at Harvard, won with an extraordinary jump. "The guys who won second and third, I could have beaten them ordinarily," he said. "I would not have won it with the jump Gutterson had. In broad jumping, once in a great while a fellow will jump way farther than he ever did in his life and better than he ever does again." Worthing ton still keeps track of the jumpers and marvels at what gold medal-winner Carl Lewis does.

He saw little of Stockholm during the games. The athletes used the ship as their hotel, with Worthing ton going into town for dinner occasionally when the prodigious weight lifters took him along. "I was the kid and they sort of looked after me," he said. Once they were at an elegant place in Stockholm where parking spaces were in short supply. "Cars were new," he told Newsday, "and this fellow couldn't get to park his machine. So these big fellows I was with got out and picked up the car and put it in the parking space. Boy, were they strong."

When the Games were over, the King of Sweden gave a party for the Americans as the winning team. The plaque Worthing ton was given and the team picture are preserved at the home of one of his daughters.

Some of the Americans stayed in Europe for other competitions. Worthing ton returned to the U.S. on the same boat and was just as sick. He went on to work his way through Dartmouth with a Tuck School major, selling Brooks Brothers clothes on campus, playing quarterback, and winning national broad jump championships in 1915 and 1916. At one time he held the amateur record of 24 feet, 8 inches.

There were no 1916 Olympics because of World War I. Worthing ton enlisted at Hanover in June 1917; he went on to become a second lieutenant. In 1918 he was part of the American Expeditionary Force at the Interallied Games held in Nice, France. According to the April 22, 1919, Boston Herald, he was "ordered to forsake everything pertaining to military work, in order that Uncle Sam (might) have its full strength against the other powers of the world."

After his discharge he earned an M. A. from the University of Chicago. He married Margaret Brink in 1921 and they had six children. He worked for several companies, including serving as president of Ditto, Inc., and achieved a reputation for "bringing old-line firms from red to black," according to the Alumni Magazine's January 1947 class notes. The Worthing tons are currently living with one of their daughters while he recovers from a broken hip.

His advice for young people who dream of Olympic competition is simple: "Work at it. Have it in mind all the time." When asked what he'd do differently if he had it all to do over again, Worthing ton was quick to answer: "I'd fly."

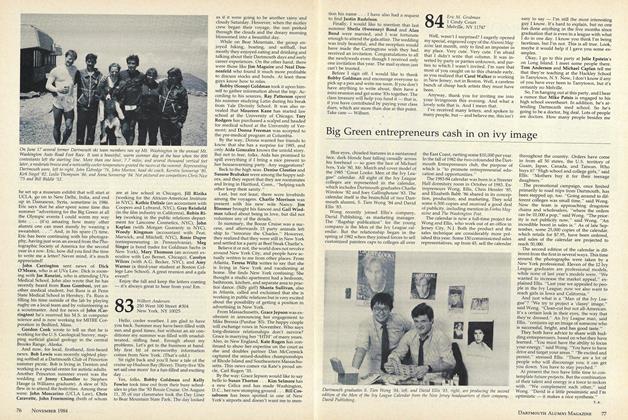

In May 1915 Harry Worthington '17 set the NewEngland Intercollegiate running broad jump record at Dartmouth with a jump of 23 feet, ten anda quarter inches. His style, which he calls the"hitch kick," was original then but is the norm forlong jumpers now.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

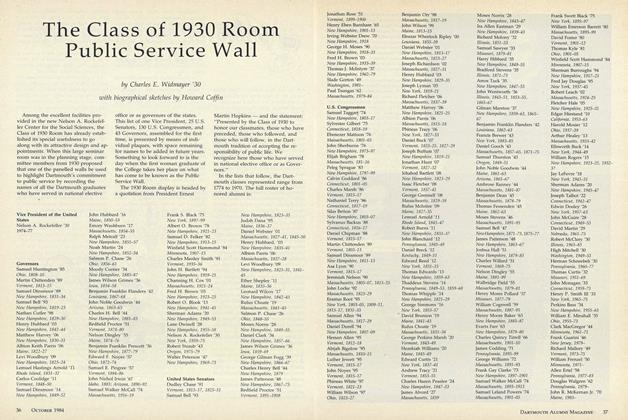

FeatureThe Class of 1930 Room Public Service Wall

October 1984 By Charles E. Widmayer '30 -

Cover Story

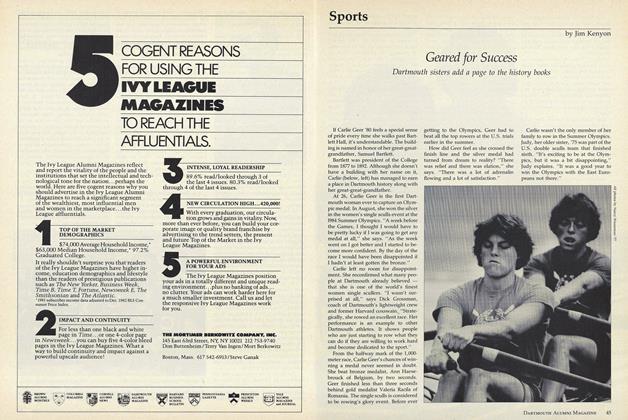

Cover StoryGeared for Success

October 1984 By Jim Kenyon -

Feature

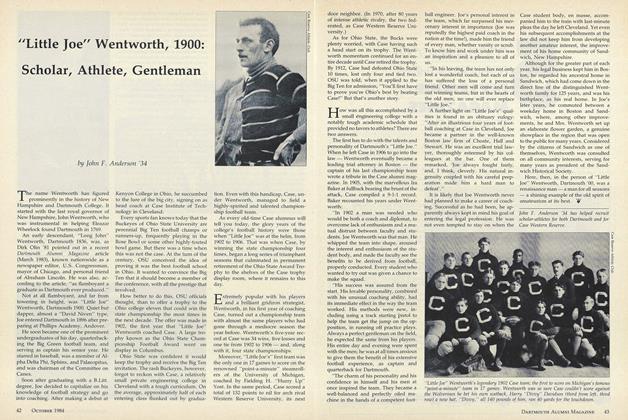

Feature"Little Joe" Wentworth, 1900: Scholar, Athlete, Gentleman

October 1984 By John F. Anderson '34 -

Feature

Feature"The Computer Revolution" Revisited

October 1984 By George O'Connell -

Article

ArticleA Post-game Peregrination

October 1984 By Dana Cook Grossman -

Article

ArticleGetting Better with Age

October 1984 By Gayle Gilman '85

T. A.

Article

-

Article

ArticleCandidates for Alumni Trustee

May, 1911 -

Article

ArticleSUGGESTIONS

May 1938 -

Article

Article181 st Commencement to be Held June 11

May 1950 -

Article

ArticleHanover Browsing

October 1938 By HERBERT F. WEST '22 -

Article

ArticleThe Compass Points North

November 1953 By R. L. A. -

Article

ArticleThis book shows how a scholar finds his fun

AUGUST 1929 By W. B. P.