For half a century, from 1923 to 1973, Dartmouth undergraduates were vaguely aware of two windmill towers on the roof of the Wilder Physics Laboratory. Rising starkly 75 feet above Wilder, they were the loftiest landmarks around until the Baker Library spire topped them in 1928.

Only a handful of students recognized them as the towers of the Dartmouth Amateur Radio Club station, WIET. A small, one-roomed shack on the Wilder roof housed the club's transmitting equipment; it was an untidy refuge, but one where Dartmouth "hams" could pursue their occult hobby of talking with other amateur radio operators across the world.

An amateur radio operator a ham is not to be confused with a citizen's band (CB) operator. CBers no longer need licenses to operate, while amateur radio operators must pass a federal examination in International Morse Code and more than rudimentary electronics. All kinds of people earn these licenses, from pre-teens to retirees seeking a hobby. Preparation for the exam can take up to two years, so a certain pride and elitism exists among those with ham radio "tickets." A huge fraternity over 410,000 amateur radio operators is now licensed in the United States, though probably fewer than 70 Dartmouth alumni are in it. For many of those few, however, Dartmouth's own amateur station was the nursery of a life-long hobby.

The Dartmouth amateur bond is strong and girdles the earth. An intercontinental network of "Big Green" operates daily at 3:00 p.m. E.S.T. on the frequency of 21,422 Mhz. Some of these amateurs carry their equipment along with them on trips so as not to miss their daily contacts with fellow alumni via the short-wave bands.

Amateur radio at Dartmouth was born right after World War I, and the first call letters issued to the College were "1YB," because in those days "Y" designated an institution of higher learning. This, with a change of law that required adding "W" or "K" as an identifying prefix for the United States, became "WIYB." Somewhat later, the club's faculty advisor failed to renew the WIYB call sign, and it was thus lost. Subsequently, WIET was assigned and is still used today.

The windmill towers were erected by the club members themselves in May of 1923. WIET was then heard well around the world a literal vox clamantis in deserto. Today, numerous modes of transmission exist single sideband phone, radio teletype, amateur television, satellite communication, etc. but at that time communication was by dots and dashes, now known as "continuous wave," or CW. Despite the primitive mode of CW (in which a telegraphtype key was used to break a circuit), the Dartmouth station made the first U.S.-to-Norway contact, and later, acting as liaison for the 1923 MacMillan arctic expedition as it advanced through the polar wastes, WIET linked up with New Zealand and with Australia at that time an incredible feat.

Radio amateurs always pride themselves on being public servants, and in the twenties and early thirties, WIET established a daily weather-reporting service with the hutmaster at Pinkham Notch, who passed the data along to Boston and to members of the College's scientific faculty. (The hutmaster, an avid ham, is said to have proposed to his future bride via radio from that wilderness.) In 1932, Alex McKenzie '32 (now WIBPI, Eaton Center, N.H.) became the first ham weather observer at the newly-established observatory on Mt. Washington.

As new operators took over from graduating ones, WIET legends and traditions accumulated. One concerns Dewitt Jones '40 (now W4BAA, Captiva Island, Fla.), who during his first freshman lecture suddenly became aware that a student next to him Ned Jacoby '40 (now NG6W in Balboa, Calif.) was whistling CW code under his breath. "CQ-CQ," he heard. "CQ" is the amateur's call inviting any other amateur station to respond. Jones wrote his call sign in bold letters on his lecture pad, and thus was born an enduring friendship.

In the days before and after World War II, the College dormitories were supplied with 220-volt direct current, and electrical devices other than lamps were banned. Operating a transmitter from a dormitory was both illegal and impractical (although, with ingenuity, it could be done). The hams who lived in fraternity houses or off-campus had an easier time of it, for they could avoid a frigid tramp to Wilder on a snowy night. Alden W. Smith '30 (now WIGAA, Temple, N.H.) recalls: "One wintry evening [I was] having a contact with a German station from my room on the top floor of my fraternity house. The transmitter was on a table in front of a partially-opened window through which the feedline to the antenna ran. Suddenly a great sheet of ice slid off the roof and hit the feedline, and the entire transmitter sailed out the window, smashing on the frozen ground three floors below. I visited my German friend several years later and had to repeat the story, again and again, to all his ham friends over glasses of superb German wine."

The original WIET shack, demolished in the mid-seventies, was perhaps 25 feet long and no wider than 15 feet a single room with benches on three sides and a large and ancient generator unit at one end. If not discreetly handled, the generator would pop a circuit-breaker in the basement of Wilder and plunge the whole building into utter darkness.

Despite the shack's disreputable appearance, it was comfortable in its isolation, and drama often occurred there, taking many forms. Dudley Russell '35 (now WOVOB, Wayzata, Minn.) recalls, for instance, a spring evening in 1934 when he was serving as night editor of The Daily Dartmouth: "It had been a dull day with not much to put in the paper. But when we got the Associated Press feed from Boston by telephone about 11:00 p.m., an item reported a major earthquake in Long Beach, Calif., with 'more to follow.' Night editors were not encouraged to spend money, but I told the AP we would call back in an hour for later developments. Meanwhile, I had one of our hams go up to WIET and try for a contact in Long Beach. Surprisingly, it worked. He contacted a ham right in Long Beach, who, despite some broken glass in his transmitter, gave us a blow-by-blow (or shake-by- shake) report. We passed this along to a startled AP when we called back, and we ended up with a pretty interesting edition."

During the 1936 Connecticut Valley flood, waters swirled up the little valley of Mink Brook, closed highways, carried away parts of the old covered bridge to Norwich, and virtually cut Hanover off from the rest of the world except for WIET. With electric service disrupted, WIET went on a round-the-clock schedule using emergency power to transmit Red Cross messages and press dispatches and to communicate with aircraft bringing in relief supplies. WIET was also able to establish contact with weak battery-operated transmitters in isolated villages and with a broadcast station in Springfield, Vermont. As far away as Cincinnati, WIET was quoted as a source of news about the New England flood.

After the Connecticut River subsided, two letters of commendation came to WIET, one from the governor of New Hampshire and a second from the American Radio Relay League. A stern rebuke from Parkhurst Hall for excessive use of the College telephone system during the flood also came but it was more than offset by the commendations.

A different kind of drama occurred once in 1935 and was not broadcast. Gene Kern '36 (now W2BAK, Tenafly, N.J.) will never forget the dark, wintry night when he and Bill Leonard '37 (now W2SKE, Washington, D.C., and recently-retired president of CBS news) were alone in the WIET shack. Kern was in contact, he writes, with some distant station, "pushing a full kilowatt up the towers and over the hills to' far away, entranced by the whine of the motorgenerator, and half-asleep. Somehow, my right hand was on the metal of the sending key while my left made contact with a switch carrying several thousand volts. It catapulted me across the room, unconscious. I came to later with Leonard perched atop me, giving artificial respiration. Miraculously, the only damage was bad burns on each hand. We kept the story to ourselves, fearful lest it reach administrative ears and result in closing down the station. I couldn't write or type for several weeks and had to explain that I'd taken one too many, fallen asleep while smoking,... hence the burns. This was readily accepted, which does not speak too well for my reputation at the time." (Modern transmitting equipment, by the way, has safeguards against such hazards.)

Frequently, the cause of romance was also furthered or bolixed by telephone patches via radio signals from WIET, Smith College being the prime target among various women's schools. One evening when a Dartmouth ham had had a blind date at Paradise Pond and the young lady had failed to charm him, he made the fact known over the air. Unbeknownst to him, the blind date's roommates had a short-wave receiver and were listening to both sides of his transmission. Everybody was appropriately embarrassed.

When Dartmouth finally smashed the Yale Jinx in 1935, the event called for an immediate extra edition of The Dartmouth. Managing editor Dick Dorrance '36 (now PP2ZDD in Brazil) and his news editor obtained photos from a New Haven paper and began an exciting ride back to Hanover. En route, they stopped at Northhampton, where they composed the headlines, dummied the front page, and transmitted it all over the air to WIET. The extra was on the street in hours.

Another "scoop" was achieved by Leonard when he relayed the 1935 Cornell game, play by play, to The Daily Dartmouth printing plant in Hanover. The issue was locked up on the press seconds after the final whistle, and papers were sold outside Memorial Stadium as the crowd exited. For those days, it was heady stuff.

Amateur radio activities at Dartmouth came to an abrupt halt on December 7, 1941. Richard W. Houghton '43 (now WIKNE, Littleton, Me.) remembers being at the microphone when word of the Pearl Harbor attack came through. Almost immediately, the Federal Communications Commission closed down all amateur stations; it would be four years until the hobby could be resumed.

In the difficult period of the early seventies, when questions of Vietnam, Cambodia, and Kent State troubled American campuses, WIET scheduled by postcard an open network conference on the Dartmouth College student strike. "I remember," says John Burns '73 (KIFMP, Nashua, N.H.), "that as soon as President Kemeny called for a moratorium on classes concurrent with similar decisions at other schools WIET went on the air and served as one of the coordinators of an East Coast moratorium network. I remember being called by many alumni hams, who were trying to fathom the campus 'situation. Most were concerned, of course, about escalating violence on college campuses and voiced the hope that if Dartmouth students were, indeed, 'striking,' they were doing so peacefully. I did a lot of reassuring during that period."

In 1973, the old windmill towers were condemned. Various reasons were rumored: they were an architectural eyesore, they were no longer structurally safe, the radio transmissions were disrupting delicate instruments in Wilder. Whatever, they were doomed. One morning, a large crane lifted them from their foundations and laid them neatly on the ground for the scrap-metal dealer. They disappeared and everyone assumed they had been collected as planned.

Shortly afterward, however, a scrapmetal crew arrived asking where the towers were. Several witnesses reported having seen a large truck drive up and some men dismantle the towers and leave with the pieces. Could anyone really steal two 75-foot windmill towers? Evidently for that's what happened. Perhaps somewhere they started a new life after serving Dartmouth's hams so faithfully.

Dewitt Jones speaks for older Dartmouth hams when he explains what the old towers meant: "Returning to Hanover and seeing those towers still in place was as good as seeing Baker at sunset. As a matter of fact, when we used to come up the road from White River, most people would look for the first sight of Baker through the trees. But not a Dartmouth ham he looked for the radio towers."

Later, the radio shack on the roof of Wilder was also demolished. WIET had moved into new quarters in the basement of Hopkins Center, beneath the Hinman post office. A Stubby beam antenna no more than 30 feet tall was erected on the roof, where it was overshadowed by the Hanover Inn on the west and the facade of the Hop on the north. In exchange for its lofty eyrie atop Wilder, the club received a small, windowless room with bleak cinder block walls.

In 1981, however, the club's star began to rise again. With substantial support from the College, the club was installed in new quarters on the second floor of Robinson Hall. But there the antennas and their tower caused interference at the College FM station, so they were moved yet again, this time to the back of Thayer Dining Hall, where they were connected to the transmitters in Robinson by a long, buried coaxial cable. Of late, WIET has been regularly on the air with a respectable signal. And coming up from Ledyard Bridge, you see the new, 50-foot tower before you see Baker Tower.

Surrounded by cards from hams the world over, sophomore DeWitt Jones '40 tunes in for a rare station.

Above left, the members of Dartmouth's new Amateur Radio Club erect twin 75-foot radio towers atop Wilder Physics Laboratory in 1923. Above, Dartmouth ham Sandy Brown '35 works on the south tower just after the 1935 Dartmouth Hall fire. Below, undergraduate Dudley Russell '35 operates WIET's "portable" transmitter at Balch Hill during the downhill run.

Club adviser Dick Schellens, WAIBDA, executive officer at the engineering school, uses WIET's new transceiver (a gift from the College) to get on the air to the Dartmouth network.

They were the loftiest landmarks around.

A great sheet of ice slid off the roof and hit the feedline, and the entire transmitter sailed out the window.

It catapulted me across the room, unconscious. I came to later with Leonard perched atop me, giving artificial respiration.

In exchange for its lofty eyrie, the club received a small, windowless room with bleak cinder block walls.

Retired naval officer and attorney Gay E.Milius Jr. '33, W4UG in Virginia Beach,Va., is currently director of the Roanoke Di-vision of the American Radio Relay League,Inc. — the headquarters society of the Inter-national Amateur Radio Union.Dick Dorrance '36, PP2ZDD, who wasexecutive director of the National Associationof FM Broadcasters and then director of pro-motion at CBS before forming his own tradepromotion company, has retired to Goias,Brazil.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureThe Draft: To Register or Not to Register

November 1984 By James Heffernan -

Feature

FeatureLife After the Presidency

November 1984 By Shelby Grantham -

Feature

FeatureGet a Job

November 1984 By Nancy Wasserman '77 -

Feature

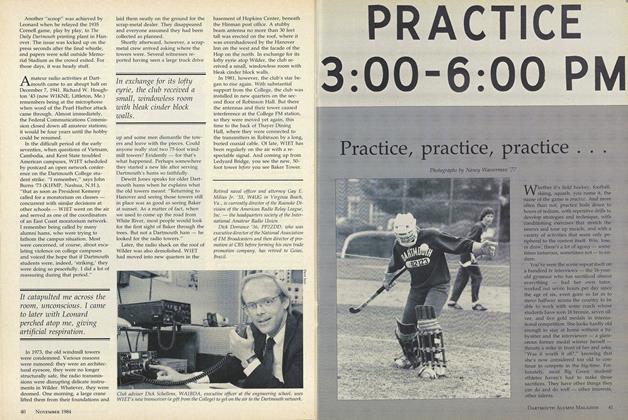

FeaturePractice, practice, practice

November 1984 -

Books

BooksSo Much More

November 1984 By Peter Smith -

Class Notes

Class Notes1948

November 1984 By Francis R. Drury Jr.

Features

-

Feature

FeatureRETIRING FACULTY AND STAFF

JUNE 1968 -

Feature

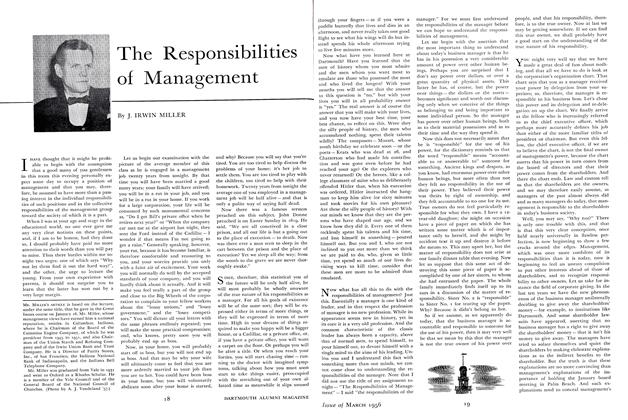

FeatureNotebook

Sept/Oct 2006 By DARTMOUTH COLLEGE SPORTS PUBLICITY -

Feature

FeatureThe Responsibilities of Management

March 1956 By J. IRWIN MILLER -

Feature

FeatureNative Americans at Dartmouth

MAY 1986 By Peter Mandel -

Feature

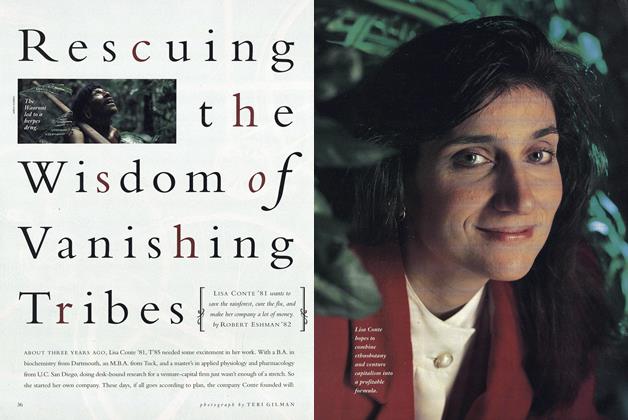

FeatureRescuing the Wisdom of Vanishing Tribes

June 1993 By Robert Eshman '82 -

Cover Story

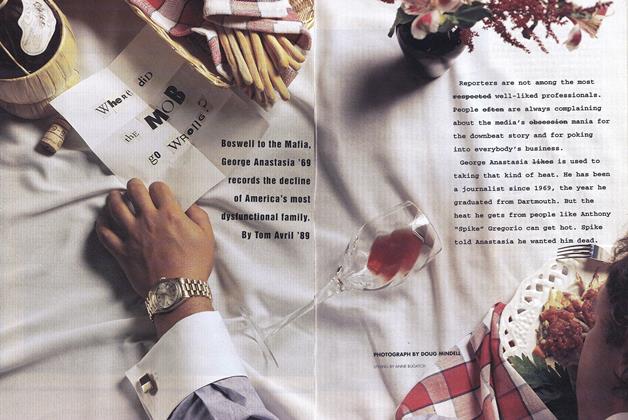

Cover StoryWhere did the Mob go Wrong?

OCTOBER 1994 By Tom Avril '89