The Chemistry of Crime

A retired government professor puts forth controversial theories that link drinking water to criminal behavior. Is he off the wall, or on to something big?

Mar/Apr 2001 CHRISTOPHER KELLY ’96A retired government professor puts forth controversial theories that link drinking water to criminal behavior. Is he off the wall, or on to something big?

Mar/Apr 2001 CHRISTOPHER KELLY ’96A retired government professor puts forth controversial theories that linkdrinking water to criminal behavior. Is he off the wall, or on to something big?

Relentless political infighting. Vast technological deficiencies. A currency that remains virtually worthless on the international market. These are among the most common explanations for why Russia's economy has failed to flourish in the post-Communist era.

But here's one theory you might not have heard before: Decades of industrial pollution in Russia have produced sky-high levels of lead in the blood of people living there.

What does this have to do with a stagnant economy? Well, lead in the blood impairs the brain chemicals that control humans' worst .impulses—the secret desire, say, to steal a TV or to land a right hook to an unfair boss's jaw. Under Communist rule, impairment to self-restraint might not have mattered. An omnipresent state police force provided all the impulse control the citizenry could need. But with the collapse of the Iron Curtain came fewer rules and fewer police—and suddenly there was nothing to contain those lead-induced impulses to play hooky from work or to mug a well-heeled guy on the street. In short, the two most essential elements of a prosperous society—industry and order—have been literally polluted.

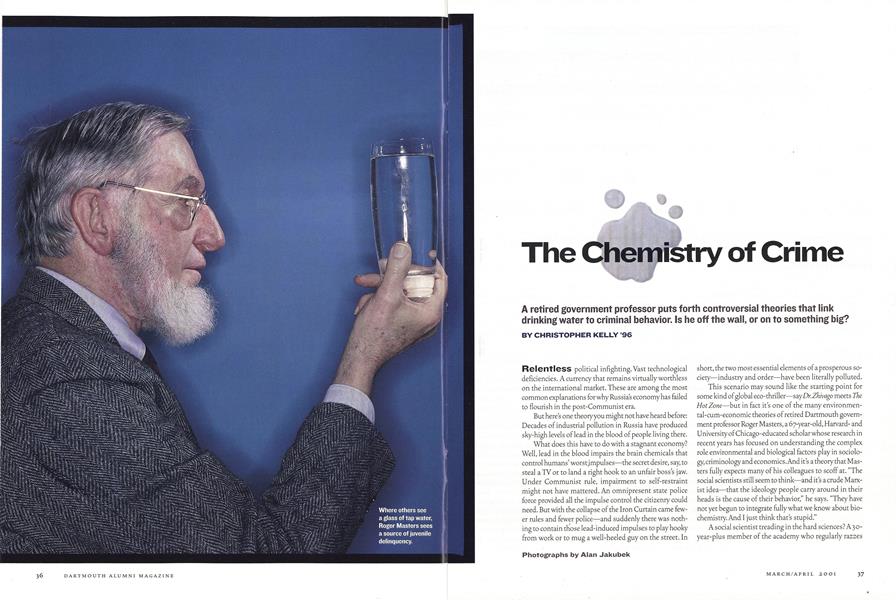

This scenario may sound like the starting point for some kind of global eco-thriller—say Dr. Zhivago meets TheHot Zone—but in fact it's one of the many environmental-cum-economic theories of retired Dartmouth government professor Roger Masters, a 67-year-old, Harvard- and University of Chicago-educated scholar whose research in recent years has focused on understanding the complex role environmental and biological factors play in sociology, criminology and economics. And its a theory that Masters fully expects many of his colleagues to scoff at. "The social scientists still seem to think—and it's a crude Marxist idea—that the ideology people carry around in their heads is the cause of their behavior," he says. "They have not yet begun to integrate fully what we know about biochemistry. And I just think that's stupid."

A social scientist treading in the hard sciences? A 30 year-plus member of the academy who regularly razzes colleagues? Such are the contradictions of the proudly iconoclastic Masters, who, while teaching at Yale in the 19605, established himself as one of the worlds foremost experts on Rousseau. In fact, it was while studying Rousseau's theories on human nature in France in 1967 that Masters first began seriously considering how biology related to government. That same year he joined the faculty at Dartmouth. In the 1980s he collaborated with the biology department in teaching a course called "Biology and Behavior" and ran summer seminars at Dartmouth for professionals interested in the effects of biology on social and legal behavior. He also conducted a series of highly regarded experiments looking at how television viewers react emotionally to political candidates' appearances in debate.

But it has been during the last four years that Masters has moved farthest into the hard sciences—first arguing that lead and manganese levels in the blood contribute to criminal behavior, and more recently contending that the widespread practice of fluoridating municipal water to improve dental health may actually increase blood lead absorption in children. This highly controversial research—which has been called "groundbreaking" by some scholars and "invalid" by others—could turn out to have vast ramifications for the way society thinks about pollution and crime.

Masters first became interested in lead and crime in the early 1990s while attending a conference on biology and juvenile crime at Florida State University. There he met a retired California oil executive named Everett "Red" Hodges, who had been garnering national attention—including a segment on ABC's 20/20—for his research arguing that higher levels of manganese in the air resulted in a higher incidence of antisocial and criminal behavior. Masters was skeptical at first, but after studying Hodges's findings he decided to look further into the issue.

Masters enlisted students Brian Hone '95 and Anil Doshi '98 to help him analyze Environmental Protection Agency data from more than 3,000 counties across the United States. They compared levels of lead and manganese emissions in communities to alcoholism rates and crime statistics. "Counties where there were high levels of alcoholism and high levels of lead and manganese had crime rates of 900 violent incidents per 100,000 people," says Masters. "The average for the entire United States is about 310 incidents. So you're tripling the crime rate." The evidence (which Masters, Hone and Doshi published in 1997) suggests something that criminologists and sociologists have heretofore failed to consider, according to Masters: "Heavy metals are one of the factors involved in crime."

Masters argues that his theories about metals can explain why so many American cities have seen a significant drop in crime over the last decade. Forget about more effective urban policing strategies or decreases in drug use or any other conventional explanation. Masters says it is the banning of leaded gasoline in the 1970s that accounts for our safer streets. "If you compare the number of gallons of leaded gasoline sold in the United States with the crime rate each year, there's no effect," he says. "But lead has its principal effect during pregnancy. And I have this rough idea that it takes 17 years to grow a criminal." In others words, take the lead out of the gasoline and 20 years hence there will be far fewer young people committing crimes.

In 1998 Masters s work caught the attention of a retired chemical engineer from Massachusetts named Myron Coplan, who for several years had been considering the possible negative effects of fluoridating municipal water supplies. "I heard there was some nut cake up at Dartmouth—that's the way he was described by Rush Limbaugh, lambasting Masters s research on his radio programblaming crime on industrial pollution," Coplan explains. "Some months later, when I learned I had a correlation between lead in water and fluoridating agents, I called Masters to find out whether he had any interest in my data."

Together Masters and Coplan found that children's blood lead levels are significantly higher in communities with fluoridated water. In 1999 they published their results in the International Journal of Environmental Studies. If correct, Masters's and Coplan's findings on fluoridation and blood-lead levels carry profound implications: A process regarded for more than 50 years as promoting one aspect of health may be harming another. And if Masters's other research is to be believed, flouridation maybe creating communities more likely to be plagued by crime and drug abuse in the future.

Masters s "neurotoxicity hypothesis" has caused a stir among scientists and social scientists. "If you look at violence in this city or that city, and say how much crime is due to fluoride and how much is due to lead, it's hard to pin down," says Dr. Albert Burgstahler, a chemist at the University of Kansas. "But I think he's got something very important that needs to be looked into further. Environmental factors on behavior have been very badly neglected." Dartmouth biology professor and dean of the faculty Edward Berger, who team-taught with Masters at his summer seminars, concurs. "The hard scientists don't necessarily believe that you can quantify human behavior," Berger says. "Roger tries to see connections and relationships in places where others are not looking. In that sense, he's always been a pioneer."

Some researchers, however, roundly criticize Masters for jumping too readily to causal conclusions based on what they feel are strictly correlational findings. Dr. Herbert Needleman, a University of Pittsburgh professor of child psychiatry and pediatrics who is an expert on lead, eplains his objections to Masters's methodology. "There are studies that look at a risk factor in individual subjects, and then compare it to an outcome—which in this case would be lead and crime. And there are studies that look at collective factors and see how they change—like lead in the air and crime rates in that city. That's what Masters does. Those kinds of studies are intriguing, but they can never prove a causal association," says Needleman, whose studies have shown that juvenile delinquents have higher concentrations of lead in their bones than control groups have. The only way Masters could prove what he's arguing, Needleman adds, is to look at lead levels in individuals and analyze those subjects' tendencies toward criminal behavior over a number of years.

An even more vocal critic of Masters s work, Dr. Edward Urbansky, a chemist with the Environmental Protection Agency's National Risk Management Research Laboratory in Cincinnati, Ohio, calls the science behind Masters and Coplan's fluoridation argument invalid. "They rely on an assumption that there's an interaction between lead and fluoride in water, but they offer no evidence for that chemically In fact, there's considerable evidence that's been published to the contrary," says Urbansky, who recently published a rebuttal to Masters and Coplan's paper on water fluoridation. Urbansky adds that he doesn't expect Masters s research to have any impact on the EPAs long-standing endorsement of municipal water fluoridation.

Masters takes his detractors in stride. "We are directly attacking their failures, so it's not surprising that their response is so vigorous," he says. He's also able to see such attacks on his work in a broader perspective—as part of a centuries-long tradition in the sciences of extreme skepticism toward new ideas.

Masters's thick skin and eclectic thinking have recently been put to the test personally as well as professionally. For the past two years, he has been waging a battle against cancer. The cancer is currently in remission. Masters believes his willingness to explore less conventional, medically unfounded approaches—acupuncture, for instance, to combat the side effects of radiation therapy—have made his fight more manageable.

For now, Masters says he and Coplan will continue to explore the relationship between fluoridation, toxic metals and human be-havior—with the hope that their work will ultimately force communities to rethink both crime prevention strategies and water fluoridation policies. And with the hope, too, that their colleagues will begin to consider the world—from Russia's economic woes to the water in our taps and the lead in children's blood—in a far more multidisciplinary light.

"Novelists understand human behavior," Masters says. "Their view is very complicated. A novelist has two people in the same household exposed to the same environment with totally different thoughts and behaviors. Novelists understand that the same causes have different effects." He pauses. "But then you go across to the social sciences, and there's nothing there. There's utter confusion once you say the old rules don't apply."

Where others see a glass of tap water, Roger Masters sees a source of juvenile delinquency.

"Roger tries to see connections andrelationships in places where others are not lookingIn that sense, he's always been a pioneer."

Contributing editor CHRISTOPHER KELLY is the film critic at the Fort Worth Star-Telegram in Texas.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Cover Story

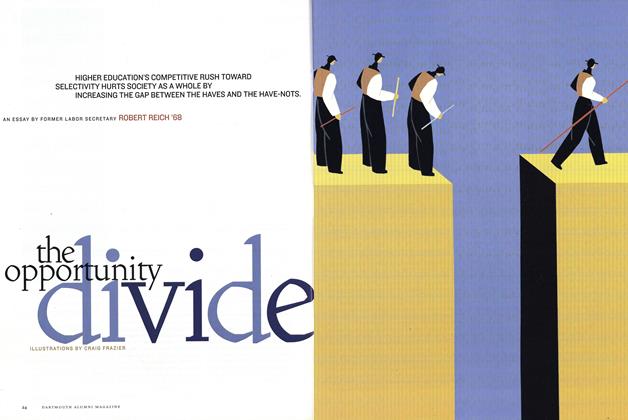

Cover StoryThe Opportunity Divide

March | April 2001 By ROBERT REICH ’68 -

Feature

FeatureRisky Business

March | April 2001 By JAMIE HELLER ’89 -

Personal History

Personal HistoryA Critical Relationship

March | April 2001 By Christopher Kelly ’96 -

Article

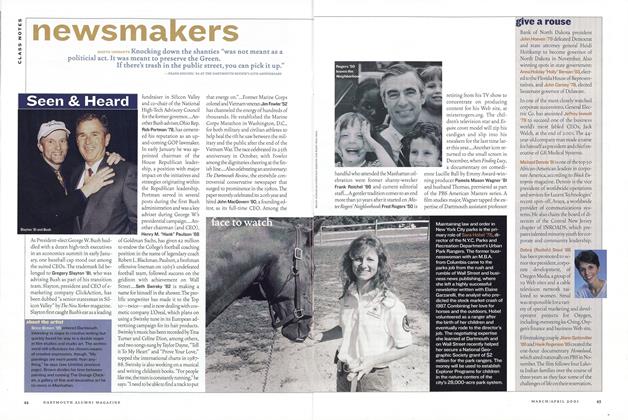

ArticleSeen & Heard

March | April 2001 -

Interview

Interview"I Was Made For This"

March | April 2001 By Henry Homeyer '68 -

Article

ArticleNorth Campus Takes Shape

March | April 2001

CHRISTOPHER KELLY ’96

-

ON THE HILL

ON THE HILLThe Film Society Turns 50

JANUARY 2000 By Christopher Kelly ’96 -

Interview

InterviewPicture Perfect

MARCH 2000 By CHRISTOPHER KELLY ’96 -

Personal History

Personal HistoryA Critical Relationship

Mar/Apr 2001 By Christopher Kelly ’96 -

Feature

FeatureBrenda and Mindy and Matt and Ben

Jan/Feb 2004 By CHRISTOPHER KELLY ’96 -

PERSONAL HISTORY

PERSONAL HISTORYBag of Tricks

May/June 2005 By Christopher Kelly ’96 -

OFF CAMPUS

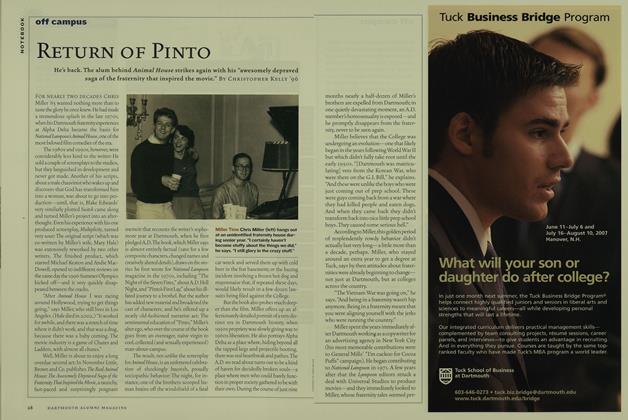

OFF CAMPUSReturn of Pinto

Nov/Dec 2006 By Christopher Kelly ’96

Features

-

Feature

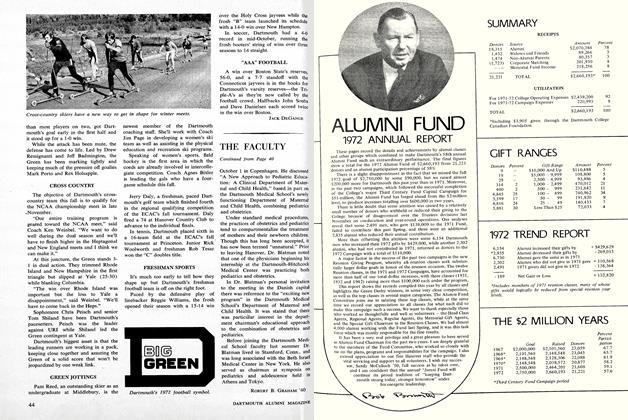

Feature1972 ANNUAL REPORT

NOVEMBER 1972 -

Feature

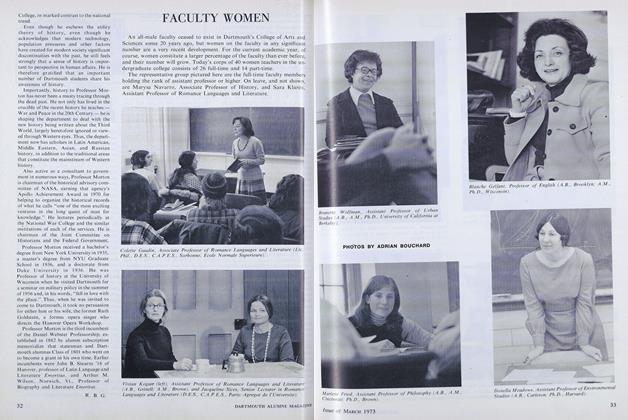

FeatureFACULTY WOMEN

MARCH 1973 -

Cover Story

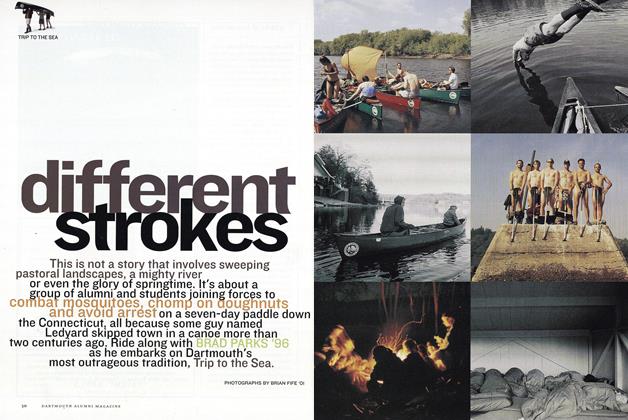

Cover StoryDifferent Strokes

May/June 2002 By Brad Parks ’96 -

Feature

FeatureCommencement

June 1975 By JAMES L. FARLEY '42 -

Feature

FeatureWhat Makes Nice People Nice?

NOVEMBER | DECEMBER 2017 By TERESA WILTZ ’83 -

Feature

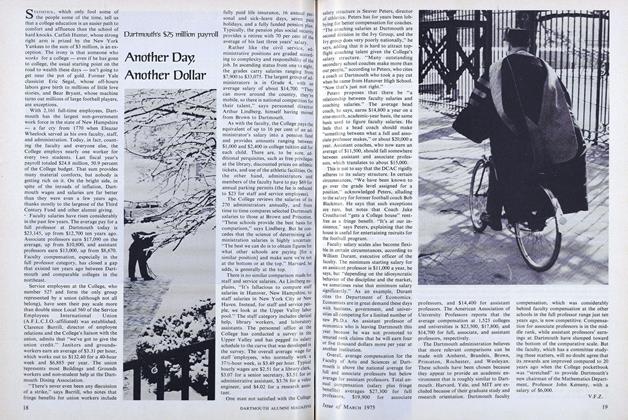

FeatureAnother Day, Another Dollar

March 1975 By V.F.Z.