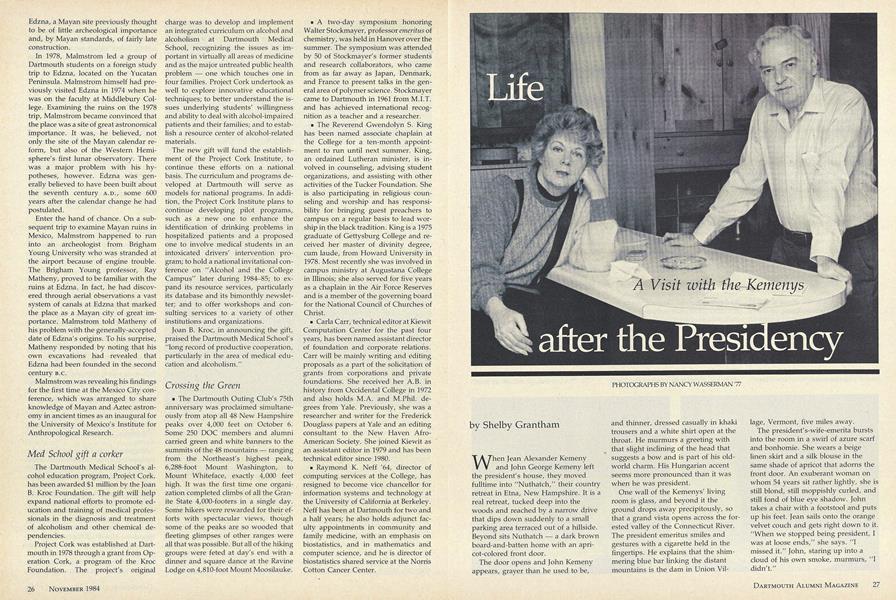

When Jean Alexander Kemeny and John George Kemeny left the president's house, they moved fulltime into "Nuthatch," their country retreat in Etna, New Hampshire. It is a real retreat, tucked deep into the woods and reached by a narrow drive that dips down suddenly to a small parking area terraced out of a hillside. Beyond sits Nuthatch a dark brown board-and-batten home with an apricot-colored front door.

The door opens and John Kemeny appears, grayer than he used to be, and thinner, dressed casually in khaki trousers and a white shirt open at the throat. He murmurs a greeting with that slight inclining of the head that suggests a bow and is part of his oldworld charm. His Hungarian accent seems more pronounced than it was when he was president.

One wall of the Kemenys' living room is glass, and beyond it the ground drops away precipitously, so that a grand vista opens across the forested valley of the Connecticut River. The president emeritus smiles and gestures with a cigarette held in the fingertips. He explains that the shimmering blue bar linking the distant mountains is the dam in Union Village, Vermont, five miles away.

The president's-wife-emerita bursts into the room in a swirl of azure scarf and bonhomie. She wears a beige linen skirt and a silk blouse in the same shade of apricot that adorns the front door. An exuberant woman on whom 54 years sit rather lightly, she is still blond, still moppishly curled, and still fond of blue eye shadow. John takes a chair with a footstool and puts up his feet. Jean sails onto the orange velvet couch and gets right down to it. "When we stopped being president, I was at loose ends," she says. "I missed it." John, staring up into a cloud of his own smoke, murmurs, "I didn't."

JAK: I missed the excitement though a lot of it was junk. I was not sure what I was going to do next. I had wanted to do more than raise children, and the presidency had given it to me. I met lots of people in that context, and suddenly I realized I would not see them again in the same way maybe I would not even see them again at all. I sputtered a lot. John did not sputter.

JGK: I knew I needed to rest for three months. It really took longer than that. We took a year, but our daughter got very ill, and so the sabbatical we expected was wiped out.

JAK: One of the first things I did was decide that it was time for us to give up smoking. We were changing our life style; it was a good time to change our smoking habits. One night I said to John, "Now!" I remember it vividly. It was the second of February 1982. We had the normal pangs of withdrawal. But then it got worse. John started giving speeches that were flat. I couldn't write. John couldn't write.

JGK: I had started teaching again and I noticed that my mind was not sharp any more. My technique was very poor. When I gave speeches, I wasn't quite there.

JAK: We went to the doctor and found out we were exhibiting all the signs of senility. The doctor explained to us that some longtime smokers just can't ever cope with withdrawing from cigarettes.

JGK: We had been off of cigarettes for six and a half months. We talked about it, and we decided deliberately that it was not worth it. A week after going back to smoking, we were both back to normal.

One way and another, say the Kemenys, they managed to get "pretty well rested," and by June of 1982, John had returned full-time to teaching for the College's Department of Mathematics, which he chaired from 1955 to 1967. A dedicated teacher, he had continued to teach throughout his 11-year presidency, giving at least two courses each year.

JGK: I remember saying something as president that came back to haunt me. Many alumni thought I would go back to teaching as a token, and I always made it very clear that I meant to do it full-time. But last year I taught what I thought must have been the heaviest load in the entire faculty: four different subjects for a total of 520 students. Then the dean of the faculty looked it up for the fun of it. It was the heaviest load anyone had.

JAK: It was hard. Just the physical presence of that many students, and the exams. He would be up until four and five in the morning correcting papers.

JGK: Part of the problem was that the first three courses were a heavy load to begin with. Then a grant came through to introduce computer literacy into finite mathematics, the fourth course, which normally attracts about 60 students, and it brought in 283!

JAK: I kept saying to him, "Cut it off, John, cut it off!"

JGK: It was hopeless. There were 220 by the end of the first day, and after that, there was no point in trying to cut it off. We could not fit into any mathematics lecture hall. I had to have Cook Auditorium. The lectures were fine. The killer was that a large fraction of the 283 students had never touched a computer before and had to be taught how to turn it on and all that sort of outside-of-class problem. I really needed help. I got ten graders and five tutors for the course 15 people. During the presidency, only 13 people reported to me.

In the lull that follows, Jean offers iced tea. "Or beer," she adds, having a second thought. Her husband chooses tea. "It's got mint in it, John. You'll just have to put up with it," she says. "Mint?" he calls after her. "But I don't mind mint!" Looking puzzled, he turns back to answer a question about retirement.

JGK: I'll be 58 next May. People misinterpret what I am doing now, and I get miffed when they ask me how it feels to be retired. Retirement to me means spending my time in different ways. I can't see myself going on teaching until I'm 70.

JAK: You might teach a little.

JGK: Don't say that, Jean. We

haven't discussed it. I think I feel it's better to cut it clean at 65.

Both of the Kemenys have embarked on new careers since leaving the presidency. In addition to teaching (and doing related research), John has started up a small company, and Jean has sold her first novel.

JGK: The big change is that we both have new careers. My wife's is more important.

JAK: Oh, come on, John. (My husband's my biggest booster.) I wrote a novel that I was sure would never get published. I researched it at the National Archives when we were in Washington during the time John was chairing the Three Mile Island Commission. I started the writing while we were not smoking, and it was awful. Flat. No oomph at all.

JGK: She was producing garbage. I can say that because what she wrote later was so very good.

JAK: After we went back to cigarettes, it started to go really well. For 11 months, I wrote every day. Normally I can't see before ten in the morning. I would get up at eight or nine, have a cup of tea, and write all morning and part of the afternoon. Four or five hours was about it then my back would be killing me. I just let it pour, and then I honed it. It was done by the summer of 1983. Then I started looking for a publisher.

JGK: She had written a hell of a good book but we had heard all the horror stories about new novelists trying to get published.

JAK: We had a friend at Houghton-Mifflin, though, and she said she would ask the editor to look at it. But I didn't really expect it would happen. For six weeks, we didn't hear. I thought it was lost.

JGK: Then she got a letter saying they would be proud to publish her "stunning novel."

JAK: It came out in September. Originally it was called Flotsam, but we changed the title to Strands of War. I wrote about what I know best Maine during World War II. Out of two incidents that happened to me, I wove a tale about how the war affects seven different people three Germans, three Americans, and a Dutch Jew. I thought it was a mystery when I started it.

JGK: It is the most devastating anti-Nazi book I have ever read in my life. Jean comes from a long line of Christians, but she hates the Nazis worse than I do. I was 13 when I left Hungary, and my grandfather died at Auschwitz. I have gotten over it. Jean has not.

JAK: I wrote a letter to Hitler when I was seven, telling him to stop killing the Jews.

JGK: She lived the book while she was writing it.

JAK: You did too.

John's business venture is a small company to promote a new version ot the ground-breaking computer language BASIC, which he and his Dartmouth colleague Thomas Kurtz invented in 1964. He describes the company as "a reluctant means to an end."

JGK: The software available for high schools is horrible. There isn't much of it, and what there is is poorly designed and written by non-teachers. At the moment there is not a decent language among those available for personal computers. All computer languages have grown and improved as computer scientists have learned their trade, and the languages out there don't reflect those changes.

The one most often used is a form of BASIC that I'm ashamed of. I've been saying for some time that a good version of BASIC for PCs was needed, and a year ago I bit the bullet when three very able systems programmers decided to strike out on their own and came to me looking for a big project. We created a small company called True Basic, with offices in Hanover. It's a private investment, a small business to design and produce a quality version of BASIC for the IBM PC and then implement the same version for other PCs.

During this explanation, Jean listens intently, chin in hand. The cigarette she holds, neglected, burns down alarmingly. "Jean!" John shouts. "Your ashes!" She comes to and deals with the cigarette, and John continues

JGK: I am chairman of the board. It has become a joke in the company that Tom Kurtz and I are to put in one day a week at the office. It comes quite often, that one day. I've been keeping impossible hours lately. We are trying to get ready a version for the Macintosh PCs the College has ordered.

JAK: He even pulled an all-nighter once recently. It was just like the old days. We are both night people, and when we were first married, all-nighters were common. But we are not as young as we used to be.

The couple work together in a large study on the lower level of the house. She works at a contemporary U-shaped desk overlooking the same magnificent view commanded by the living room. He uses an old-fashioned kneehole desk that faces the wall at the other end of the room. A modern table nearby holds his personal computer. They have no trouble working in the same room, he says: "The typing doesn't bother me and I long ago got used to her swearing." The study is their own creation, an expansion of the rather small house they bought in 1975 as a retreat from the pressures of the presidency.

JGK: One thing we have noticed lately is how much quieter it is here than on Webster Avenue.

JAK: It's a whole different life. There are a lot of things in Hanover that I just don't get to anymore. I dislike going into town every day. It's 20 minutes each way.

JGK: I get down more because I'm teaching and because of the company, but I have a PC downstairs, and I also try to arrange days on which I don't go in.

JAK: We haven't given a single big party since the presidency. I don't think I ever will again.

JGK: Last year it hit us that with Jean writing and me in the new company, we have almost no social life.

JAK: We are both guarding our time. I hate housework now more than ever, and we have a cleaning group that comes in to do a whirlwind cleanup of the house every two weeks. We do the extra vacuuming in between, and the laundry John does his and I do mine. JGK: You cook, and I do the dishes.

One aftermath of the presidency, explains Jean, was a seige of honorary degress and requests to deliver commencement speeches "all over the country and in Canada." But once those trips were over, the Kemenys cut down drastically on their long-distance traveling.

JGK: We decided we ought to explore our own area. So we spent the summer seeing Vermont.

JAK: We went to Manchester and spent three days in an inn, for instance. We explored the area, went to art galleries and ate. We had a wonderful time finding good places to eat. And just being alone with each other.

JGK: In a very real sense, we are each other's best friend. The presidency brought us closer together. It had been a good marriage before, but it became special during the presidency.

JAK: I worried that it would change again, the marriage, when the presidency ended. But we are staying close. John has taken an enormous interest in what I'm doing and is proud of me, and I am finding his new company fascinating. I had hoped for that, but not expected it. We are doing more things together. Before, we just came home and collapsed that was "being together."

The Kemeny children, Jenny and Rob, have both long since graduated from Dartmouth and left the nest. Jenny is currently enrolled as a doctoral candidate in the Sloan School of Business at MIT. Divorced and remarried, she seems, according to her parents, to be well and happy. Their son went into retailing in 1977, married, and recently embarked on a serious managerial career, having accepted a position in Los Angeles as a division manager of furniture and Oriental rugs for Bullock department stores.

One of the other things the Kemenys do together these days is tend on some 16 raccoons. They had their first coon visitor in 1977, explains Jean, indicating the glass doors leading to the deck outside. The doors are blurry with pawprints.

JGK: Occasionally, we wash them off. The raccoons give us much pleasure, especially the nursing mothers who bring their young to visit.

JAK: The first one came when we were coming here just for weekends, and when I realized what it was I was so excited I couldn't speak. I fed it Hungarian goulash that was all I had in the house and we named it Moysha. We found out it was a she when she brought her baby, which we named Shalom. Now we have their great-great-grandchildren.

JGK: Sometimes we lose track, but there are three main lineages.

JAK: It's great fun to watch them, especially when you're tired. We feed them kibble dogfood and leftovers from Thayer Dining Hall.

JGK: We don't try to domesticate them.

John excuses himself to change for an engagement in town, and Jean brings out some of the animal photographs she has taken. They are beautiful shots, one of a pileated woodpecker taken from her bedroom window and another of nuzzling elephants taken at a zoo.

Jean excuses herself in turn, and John offers a tour of the rambling house, no holds barred, from the master bedroom with its unmade bed to Jean's salon of a bath with sunken tub. We are in the downstairs storeroom viewing boxes of still-unsorted presidential papers when there is a shout from Jean: "John! The coons are here!" We rush upstairs to find two very large and proprietary raccoons peering through.the glass doors. Moving quietly so as not to frighten them, Jean gets a packet out of the refrigerator and gives it to John. "Is that your friend?" he asks her, sotto voce. "No," she whispers. "My friend has a scar. It's another one. But he can have the cornbread."

The president emeritus gets down on his hands and knees, eyeball to eyeball with the coons, and opens the doors. He proffers the cornbread. The animals regard him carefully, even a little suspiciously. Then they waddle forward and accept his offering. He smiles with pleasure.

A Visit with the Kemenys

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureThe Draft: To Register or Not to Register

November 1984 By James Heffernan -

Feature

FeatureHamming It Up

November 1984 By Gay E. Milius, Jr. '33 and Dick Dorrance '36 -

Feature

FeatureGet a Job

November 1984 By Nancy Wasserman '77 -

Feature

FeaturePractice, practice, practice

November 1984 -

Books

BooksSo Much More

November 1984 By Peter Smith -

Class Notes

Class Notes1948

November 1984 By Francis R. Drury Jr.

Shelby Grantham

-

Feature

FeatureWomen at the Top (almost)

May 1977 By SHELBY GRANTHAM -

Article

ArticleMagic in the Museum

Jan/Feb 1981 By Shelby Grantham -

Article

ArticleMaster Carpenter, Journeyman Blackmailer

NOVEMBER 1981 By Shelby Grantham -

Cover Story

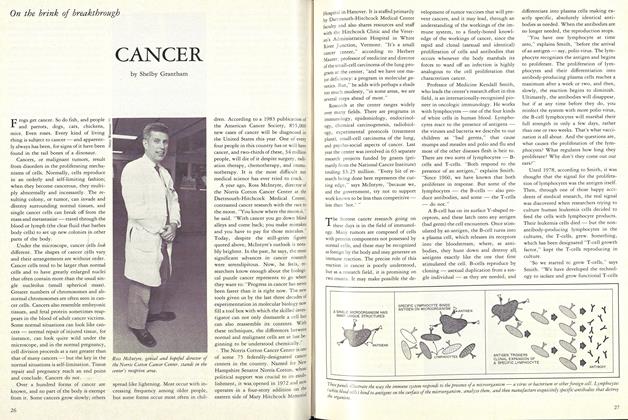

Cover StoryCANCER

APRIL 1983 By Shelby Grantham -

Feature

FeatureThe Dinan Decade

OCTOBER, 1908 By Shelby Grantham -

Feature

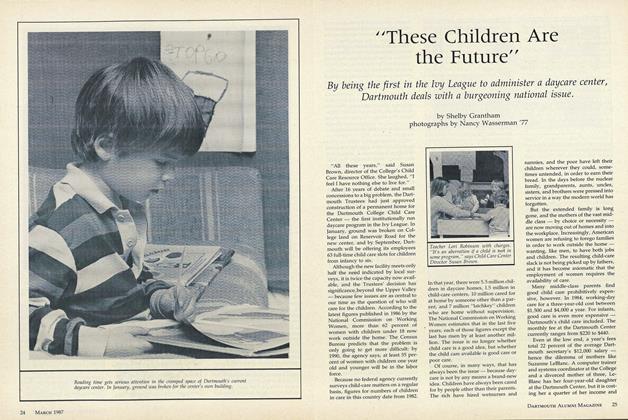

Feature"These Children Are the Future"

MARCH • 1987 By Shelby Grantham

Features

-

Feature

FeatureThe Convocation Address

November 1956 -

Cover Story

Cover StorySartorial Splendor

April 1981 -

Feature

FeatureSIENNA CRAIG

Sept/Oct 2010 -

Feature

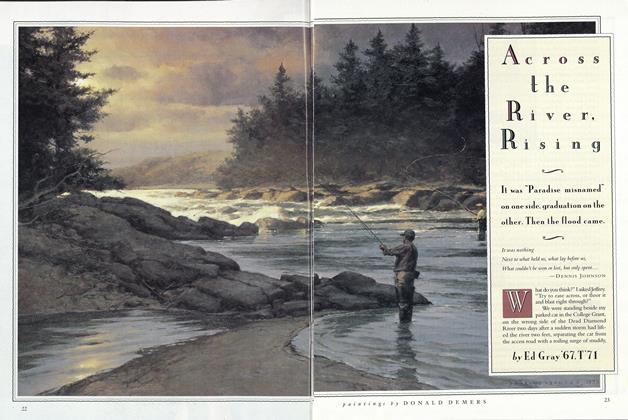

FeatureAcross the River, Rising

May 1993 By Ed Gray '67, T '71 -

Feature

FeatureIt's Spring and Job Time for Seniors

By JAMES B. FISHER '54 -

Feature

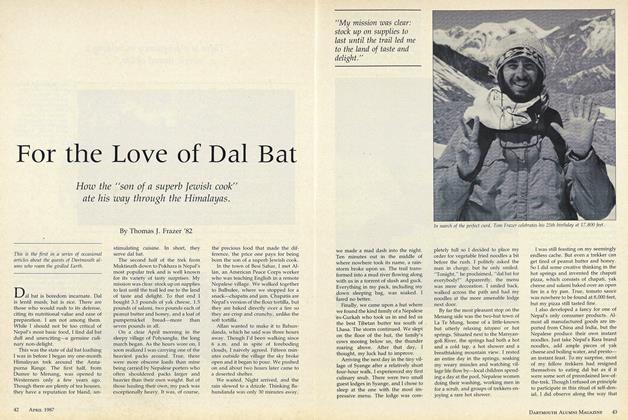

FeatureFor the Love of Dal Bat

APRIL • 1987 By Thomas J. Frazer '82